Listening to Leaders 2025

Development cooperation over a decade of disruption

Samantha Custer, Ana Horigoshi, Bentje Boer, and Kelsey Marshall

April 2025

1. Introduction: Development cooperation in a time of disruption

1.1 A decade of Listening to Leaders—who, what, and why?

1.1.2 Which development partners?

1.1.3 How did leaders share their views, and on which topics?

2. Footprint: With whom are Global South leaders working?

2.1 The footprint of development cooperation in 2024

2.2 Changes over time in the footprint of development cooperation

3. Performance: How do leaders rate development partners?

3.1 The perceived performance of development partners in 2024

3.1.1 Global heavyweights: Top performers across geographies and sectors

3.1.2 Specialized star power: Niche areas of comparative advantage

3.2 Changes over time in the ratings of development partner performance

4. Attraction: What do leaders look for in their partners?

4.1 Performance perceptions across leaders of different types

4.2 What makes development partners influential and helpful?

4.3 What attributes do leaders value most in a development partner?

Figure 1. Expansion in geographic coverage of the Listening to Leaders Survey, 2014 to 2024

Table 1. Listening to Leaders: Sampling frame and sample for analysis

Table 2. Development partners with their acronyms, by cohort

Figure 2. Top 10 largest development partners overall by perceived footprint, 2024

Figure 3. Perceived footprint of traditional multilaterals as a cohort, 2024 snapshot

Figure 4. Perceived footprint of traditional bilaterals as a cohort, 2024 snapshot

Figure 5. Perceived footprint of non-traditional bilaterals as a cohort, 2024 snapshot

Figure 6. Perceived footprint of non-traditional multilaterals as a cohort, 2024 snapshot

Figure 8. Change in footprint, traditional multilaterals, 2017 to 2024

Figure 9. Change in footprint, traditional bilaterals, 2017 to 2024

Table 3. Historical ODA (2023) and announced aid budget cuts by selected traditional bilaterals

Figure 10. Change in footprint, non-traditional bilaterals, 2017 to 2024

Figure 11. Top 10 most influential development partners overall, 2024

Figure 12. Top 10 most helpful development partners overall, 2024

Figure 13. Influence by region and sector, top 35 development partners, 2024

Figure 14. Helpfulness by region and sector, top 35 development partners, 2024

Box 1. Looking back at a decade of U.S. performance to anticipate potential future changes

Figure 15. Why did respondents view development partners as being influential?

Figure 16. Why did respondents view development partners as being helpful?

Figure 17. What did leaders say they valued most in a development partner?

Figure 18. What did leaders say made a development partner adaptable?

Figure 19. What did leaders say made a development partner prioritize long-term planning?

Acronyms

ADB Asian Development Bank

AFDB African Development Bank

AIIB Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank

AMF Arab Monetary Fund

ARE United Arab Emirates

AUS Australia

AUT Austria

BADEA Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa

BEL Belgium

BM GF Gates Foundation (formerly Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation)

BRA Brazil

BRI Belt and Road Initiative

BRICS Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa

CAF Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean

CABEI Central American Bank for Economic Integration

CAN Canada

CDB Caribbean Development Bank

CHE Switzerland

CHN China

CSO Civil society organization

DAC Development Assistance Committee

DEU Germany

DFC Development Finance Corporation

DNK Denmark

DoS US Department of State

EAP East Asia and Pacific

EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

ECA Europe and Central Asia

ESP Spain

EU European Union

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization

FF Ford Foundation

FIN Finland

FRA Framce

GAVI Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization

GBR Great Britain/United Kingdom

GCF Green Climate Fund

GEF Global Environment Facility

GF Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria

G7 Group of Seven

IDB Inter-American Development Bank

IFAD International Fund for Agricultural Development

IFC International Finance Corporation

IFI International Finance Institution

IMF International Monetary Fund

IND India

IRL Ireland

ISDB Islamic Development Bank

ISR Israel

ITA Italy

JBIC Japan Bank for International Cooperation

JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency

JPN Japan

KOR South Korea

KWT Kuwait

LAC Latin America and the Caribbean

LBY Libya

LIC Low-income country

LtL Listening to Leaders

LUX Luxembourg

MCC Millennium Challenge Corporation

MEX Mexico

MENA Middle East and North Africa

MIGA Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency

NGO Non-governmental organization

NLD Netherlands

NOR Norway

NZL New Zealand

ODA Official development assistance

OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

OFID OPEC Fund for International Development

OPEC Organization for Petroleum Exporting Countries

PRT Portugal

QAT Qatar

RUS Russia

SA South Asia

SAU Saudi Arabia

SDGs Sustainable Development Goals

SIDS Small Island Developing States

SSA Sub-Saharan Africa

SWE Sweden

TUR Turkey

TWN Taiwan

UAE United Arab Emirates

UK United Kingdom

UN United Nations

UNDP United Nations Development Program

UNEP United Nations Environment Program

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

UNFPA United Nations Population Fund

U.S. United States

USA United States of America

USAID U.S. Agency for International Development

VEN Venezuela

WB World Bank

WFP World Food Program

WHO World Health Organization

ZAF South Africa

Executive Summary

Disruption has defined the last decade of development cooperation—from climate change and global epidemics to persistent conflicts and geopolitical competition. To preserve past gains and advance progress, Global South countries mobilized domestic resources at home and cooperated with numerous bilateral agencies and multilateral organizations from abroad. Using four AidData surveys conducted between 2014 and 2024, we analyze how leaders representing 148 countries and territories rate the performance of their external development partners, how these attitudes evolved over the decade, and what factors might explain these perceptions.

We use the term leader broadly to include mid- to senior-level government officials, representatives from civil society and the private sector, and independent experts from universities, media, and think tanks who work closely with development partners in their countries. In this report, we examine the performance of individual development partners against the full field of players and compared to those in their closest cohort group: traditional OECD bilaterals, traditional multilaterals, non-traditional bilaterals, and non-traditional or Southern-led multilaterals. We collapse responses for all agencies flying the same flag into a unified score for each measure.

Footprint: With whom are Global South leaders working?

Global South leaders reported receiving advice or assistance from 71 bilateral and multilateral actors in the 2024 survey wave. We calculate the percentage of respondents who reported receiving advice or assistance from each development partner to measure that actor’s footprint. This measure provides important context to understand the size and diversity of each development partner’s constituency base. Typically, the largest partners worked with one-fifth or more of the leaders surveyed, while the smallest worked with 1 percent or fewer.

Three key takeaways about the footprint of development cooperation over the last decade:

- Traditional multilaterals and OECD bilaterals still worked with the most Global South leaders in 2024, proving durable in an age of expanded choice

- Despite waning multilateralism, traditional multilaterals held steady or expanded their footprints, while many OECD bilaterals have lost ground since 2017

- China remains the front-runner among non-traditional players, both bilateral or multilateral, and works with more leaders and countries, but this growth may be slowing

Performance: How do leaders rate development partners?

Global South leaders generally viewed their development partners favorably. In 2024, the average development partner was rated as influential by roughly three-quarters (72.4 percent) of the leaders they worked with and helpful by four-fifths (81.8 percent) of this group. However, averages can obscure attitudes towards specific partners. There was a 37 percentage point difference between the most and least influential development partners, the Global Fund (92.1 percent) and Brazil (55.1 percent), in 2024. That year, there was a gap of 29 percentage points between the most and least helpful partners, Portugal (96 percent) and Qatar (67 percent).

Two key takeaways about the performance of development cooperation over the last decade:

- Non-traditional players have not yet displaced traditional multilaterals and OECD bilaterals, who still dominated the leaderboard on influence and helpfulness in 2024

- BRICS and Middle Eastern development partners were among the most improved, charting big performance gains over the decade, but still lagging traditional players

Attraction: What do Global South leaders look for in their partners?

The decisions of bilateral aid agencies and multilateral organizations regarding how much they are willing to invest, where, and in what certainly affect the choices available. However, Global South leaders ultimately determine with whom they want to partner to catalyze socio-economic progress for their countries. In this report, we assessed the odds that leaders of different types rate development partners more or less favorably, examine the ingredients leaders consider important in explaining the performance of development partners, and assess the attributes leaders say they value most in a partner.

Three takeaways about what development partners look for in their partners:

- Money matters, but leaders in some country contexts—lower income, democratic, and moderately vulnerable countries—are more predisposed than others to view partners favorably

- Resources, respect, and relationships were top-of-mind for Global South leaders explaining what made development partners top performers

- Global South leaders place a premium on development partners willing to adapt their strategies to local needs and plan for long-term sustainability

Conclusion: Reimagining future development cooperation

If the past decade was one of disruption, the next decade does not promise fairer weather for development cooperation. Traditional bilaterals are retreating from earlier official development assistance commitments. Multilaterals must contend with rising skepticism and declining core contributions. Global South countries are questioning whether conventional aid has done more harm than good, while rising powers are challenging the traditional rules of the game and advocating for South-South Cooperation as a sustainable alternative.

In the next decade, development cooperation will likely be reimagined, as government and international organizations revisit how they create, finance, and deliver value in support of Global South countries. As we consider how development cooperation can and should evolve, the Listening to Leaders surveys highlight three opportunities for action:

- Reorient future cooperation around shared prosperity and mutual benefit: Bilateral cooperation could identify areas of shared interest that are responsive to what Global South counterparts want, while strategically aligned with a donor’s national interests.

- Safeguard multilateral venues with an expanded voice for middle powers: Traditional multilaterals could position themselves as trustworthy venues to adjudicate between conflicting interests in ways that strengthen the negotiating power of non-traditional development partners and low- and middle-income countries. As traditional bilaterals cut back their aid and engagement, non-traditional development partners and Global South countries may increasingly represent the future of multilateral cooperation.

- Get serious about policy coherence and a broader suite of economic tools: As aid is likely to be in increasingly short supply in the coming decade, it will be even more important for development partners to focus on creating synergies between aid and other tools of economic statecraft, such as trade, foreign direct investment, and remittances. This implies that international organizations and government agencies need to walk the talk of “policy coherence,” ensuring broader economic policies are helping, not hindering, this goal.

Acknowledgments

The 2025 Listening to Leaders (LtL) report was prepared by Samantha Custer, Ana Horigoshi, Bentje Boer, and Kelsey Marshall (AidData, William & Mary). John Custer and Sarina Patterson supported this publication’s layout, editing, and visuals. This edition spans four global surveys conducted by AidData over a decade (2014, 2017, 2020, 2024). In this respect, this publication would not have been possible without the support of many individuals who gave their time and talents as research assistants, collaborators, or external reviewers over the years.

Although they remain unnamed to maintain anonymity, this research crucially relied upon the more than 20,000 responses from survey participants from 148 countries and semi-autonomous territories, who shared their invaluable insights on development partner performance. We also appreciate supportive funding partners who contributed general operating support to the survey or commissioned custom analyses that defrayed the cost of providing this report as a public good. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

We express our sincere gratitude to each of the following individuals and institutions for their invaluable contributions to one or more of the surveys featured in this report:

- LtL Staff and Research Assistants: Nour Aburish, Harrison Abramsohn, Brandon Aheimer, Raffaela Alhach, Mehr Ali, Nada Aljassar, Lana Altunashvili, Grace Anderson, Haley Arata, Dawn Bangi, Abigail Barnes, Danielle Batterman, Khadijah Bea, Alondra Belford, Andrew Bell, Ori Ben-Ari, Anne Bergman, Bentje Boer, Hanna Borgestedt, Heather Blackwell, Hunter Blackwell, Michael Blakely, Eric Brewer, Daniel Brot, Grace Bruce, Bryan Burgess, Riley Busbee, Matthew Bynum, Caroline Byrne, Gabriella Cao, Nicholas Cardozo, Mengfan Cheng, Vera Choo, Riley Companion, Abigail Crews, Jasmine Curry, Samantha Custer, Makayla Cutter, Ashley Darang, Caroline Davis, Megan Davis, Damiana Dendy, Catherine Denton, Sarah DeVellis, Matt DiLorenzo, Jack Doherty, Sarah Dowless, Hanyi Dou, Emily Dumont, John Eckert, Codi Elliott, Salma Elsayed-Ali, Weldon Emerson, Madeleine Engler, Agustina Eskenazi, Khaile Forbes, Julia Gloudeman, Lexi Godfrey, Leonor Grave, Riley Graham, Emma Groene, Maria Haddad, Elizabeth Hagen, Hannah Hampton, Thompson Hangen, Carrie Hartgrove, Duenya Hassan, John Hoskins, Sariah Harmer, Ani Harutyunyan, Cassie Heyman-Schrum, Ana Horigoshi, Amber Hutchinson, Megan Jenkins, JT Kaufmann, Patrick Kavanaugh, Luka Klimaviciute, Rodney Knight, Emma Landi, Rebecca Latourell, Kristen Lauritzen, Lisa Lee, Hannah Lee, Nicholas Lee, Ziwei Li, Jason Lin, Haowen Liu, Jingjing Liu, Samyuktha Mahadevan, Kelsey Marshall, Takaaki Masaki, Benoit Mathieu, Caitlin McTiernan, Austin Morrison, Rachel McGraw, Holden Mershon, Noelle Mlynarczyk, Ankita Mohan, Lehman Montgomery, Erin Murphy, Salina Natnael, Cassie Nestor, Kara Newman, Caroline Nutter, Matthew Nwaneri, Yaw Ofori-Addae, Ben Olinger, Laura Opsahl-Ong, Joanne Owens, Catalina Palma, Bradley Parks, Elaine Perkins, Megan Pierce, Ryan Posthumus, Laura Powell, Brigid Rawdon, Chesney Reid, Zachary Rice, Joshua Richards, Grace Riley, Kristin Ritchey, Peter Rizkallah, John Roakes, Jacob Rodrigues, Allison Rohrer, Christopher Rossi, Sarah Salem, Annelise Schader, Claudia Segura, Tanya Sethi, Rose Shafer, Ramona Shelton, Shahzeb Siddiqui, Madeline Smith, Rafael Snell-Feikema, Chris Soldan, Minkyong Song, Megan Steele, Alena Stern, Lauren Su, Adrianne Sugden, Rishya Suresh, Anahita Suri, Michael Testa, Semira Tewolde, Brendan Thomas, Jessica Tiblin, Morgan Tompkins, Undra Tsend, Jioni Tuck, Marie Tummarello, Halla Walcott, Dongyang Wang, Clara Waterman, Brianna Vetter, Mikayla Williams, Taylor Wilson, Diana Winters, Angela Yost, Alex Yung, and Jack Zhang

- LtL Peer Collaborators and External Reviewers: Jihee Ahn, Norma Altshuler, Rob Blair, Bryan Burgess, Grant Cameron, Maria Arnal Canudo, Jack Cornforth, John Custer, Matt DiLorenzo, Elizabeth Dodds, Emilie Efronson, Catherin Elkins, Joerg Faust, Sharon Felzer, David de Ferantti, Anthony Gao, Rasmus Heltberg, Mirko Heinzel, Jennifer Hudson, Galina Kalvatcheva, Parker Kim, Paige Kirby, Charlotte Lane, Rachel Leeds, Ammar A. Malik, Peter McDermott, Ida McDonnell, David McNair, Ahmed Naseer, Kathy Nolan, NORC at the University of Chicago, Soomin Oh, Brad Parks, Sarina Patterson, Suma Pratyusha, Annalisa Prizzon, Bernhard Reinsberg, Phil Roessler, Mark Skeith, Ariel Swan, and Llanco Talamantes, Huitang Tang, Jennifer Turner, Jessica Wells, Hannah Wheatley, and Alex Wooley

- LtL Contributing Funders: Danish International Development Agency (Danida), Ford Foundation, Gates Foundation, Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, German Institute for Development Evaluation (DEval), Inter-American Development Bank, International Monetary Fund, John Templeton Foundation, London School of Economics and Political Science, Smith Richardson Foundation, United Kingdom Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office, United Nations Development Program, United States Agency for International Development, the University of Glasgow, William & Mary, World Bank, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation

Citation

Custer, S., Horigoshi, A., Boer, B., and K. Marshall. (2025). Listening to Leaders 2025: Development cooperation over a decade of disruption. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary.

1. Introduction: Development cooperation in a time of disruption

If there is a single word that describes the landscape of development cooperation [1] over the last decade, it is disruption. Extreme weather events and global pandemics spared no country and compounded vulnerabilities for resource-constrained communities (World Economic Forum, 2025; OECD, 2023a; Fund for Peace, 2022). Hot conflicts became more numerous and cyclical, threatening long-term development gains across continents (Ero and Atwood, 2024; Palik et al., 2022). Intensified geopolitical competition encouraged countries to be more transactional in their foreign policy, with development as a venue for contestation (Ikenberry, 2025 ; Aly et al., 2025). Inequality within countries rose, even as it fell between countries, fueling distrust in institutions and apathy towards democracy (UN, n.d.; Wike and Fetterolf, 2021).

To navigate this decade of disruption, leaders in low- and middle-income countries mobilized domestic resources and ingenuity at home while partnering with many external development partners—bilateral aid agencies and multilateral organizations—from abroad. This report analyzes the performance of these external development partners in delivering value to those who rely on their policy advice or financial assistance. It surfaces 360-degree feedback on performance from the perspective of public, private, and civil society leaders who make and shape development policies in the Global South. It does not attempt to synthesize or duplicate the array of studies that assess aid’s effectiveness at the project, community, or portfolio level. Nor does this publication replicate critical global trends analysis of leading institutions that assess risks, monitor progress, and track hotspots of poverty and deprivation.

For more than a decade, AidData (a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute) has been at the forefront of efforts to help development partners better respond to the priorities, preferences, and perspectives of counterparts in low- and middle-income countries. In this report, we bring together for the first time four of our global Listening to Leaders (LtL) surveys conducted at critical intervals during this decade of disruption in 2014, 2017, 2020, and 2024. These surveys covered a wide range of topics, some of which will be analyzed in subsequent publications. In this report, we focus on a subset of responses related to three perception-based measures of how leaders interact with international development partners:

- Footprint: From which development partners do Global South leaders receive advice or assistance, and how has this evolved?

- Influence: Which development partners are most and least influential in shaping the domestic policy priorities of leaders in the Global South—and why?

- Helpfulness: Which development partners do Global South leaders consider most and least helpful in implementing policy changes in their countries, and why?

The answers to these questions are valuable in several use cases. Development partners can use this information to optimize future assistance efforts. Global South leaders and watchdog groups can leverage this data to inform dialogue with development partners over reforms to make assistance more accountable and responsive. In a world where multiple powers jockey for competitive advantage, policymakers may also find these insights useful for conversations about whether and under what conditions development finance helps them project global influence.

In the remainder of this chapter, we provide more information about how we use the Listening to Leaders survey to answer our three research questions by describing (i) who participated in the survey, (ii) which development partners they evaluated, and (iii) on which dimensions partners were assessed.

1.1 A decade of Listening to Leaders—who, what, and why?

Government officials, private sector leaders, and civil society representatives influence innumerable decisions that affect their country’s development trajectory and relations with external partners. Yet, there is a dearth of information readily available about the preferences and experiences of these influential elites. Over the past decade, AidData has surveyed public, private, and civil society leaders across 100+ countries and semi-autonomous territories about their development priorities and experiences working with various partners. Each survey was conducted online via the Qualtrics management platform over 4 to 6 weeks.

The four waves of the LtL survey span eleven years (2014-2024), which allows us to analyze how leaders’ attitudes toward development partners change over time. Of the 20,269 survey responses received from leaders over the years, this report focuses on the roughly 13,000 responses that rated development partner performance. While we only briefly introduce the LtL survey here, the technical appendix provides additional detail.

1.1.1 Which leaders?

AidData uses the term “leader” broadly to capture perspectives from a range of individuals who make or shape development policy across the Global South. A panoply of polls tracks citizen priorities and attitudes towards foreign powers or institutions in the general population. It has historically been more difficult to surface the viewpoints of Global South policymakers who directly interact with the marketplace of development finance suppliers. Listening to Leaders is uniquely positioned to help close this gap by focusing on individuals who, because of their positions and expertise, work most closely with development partners and whose familiarity with these actors better equips them to evaluate their performance.

Common hurdles in conducting elite surveys include identifying who holds relevant knowledge to share, contacting these individuals, and motivating them to share their perspectives. While the true population of Global South leaders involved in making and shaping development policy is largely unobservable, our methodology produces the next best thing: a well-defined sampling frame systematically curated over ten years to roughly represent the population of interest across 23 sectors of development policy.

Rather than the convenience samples used by market research firms, AidData uses institutional position maps to identify positions and people within government agencies and organizations who make or shape decisions relevant to our research questions. The 2024 sampling frame included 66,000 individuals representing diverse stakeholder groups of interest covering 148 countries and semi-autonomous territories. Stakeholder groups in the sampling frame include: (i) mid-level to senior government officials working in executive branch agencies; (ii) representatives of civil society organizations (CSOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who implement projects and advocate for policies; (iii) leaders of private sector companies; (iv) local representative of bilateral and multilateral development partners operating in country; (v) independent experts from universities, think tanks, and media; and (vi) parliamentarians.

Our development of the sampling frame has been relatively consistent over the past decade. Beyond annual updating, the research team made minimal alterations to four stakeholder groups across the LtL survey waves, including: government officials, civil society, private sector, and local development partner representatives. In some cases, we fine-tuned stakeholder groups to better capture the population of interest. In 2020, the independent expert category was refined to focus on in-country experts; previously, it allowed for the inclusion of experts outside the country. A new group for parliamentarians was added in 2020 but dropped in 2024. AidData expanded the sampling frame to include additional geographic areas from 126 countries and territories in 2014, to 141 in 2020, and 148 in 2024 (see Figure 1).

Fielded between February and June 2024, 49,000 individuals successfully received an email invitation to participate in the 2024 Listening to Leaders survey. Of these individuals, 3,250 participated for an overall survey response rate of 6.58 percent. Table 1 below summarizes the sampling frame, sample, and response rate information for each of the four LtL surveys in general, and specifically for the partner performance module. Individual-level participation rates in email and elite surveys tend to be lower than those of household and in-person surveys.

Figure 1. Expansion in geographic coverage of the Listening to Leaders Survey, 2014 to 2024

Table 1. Listening to Leaders: Sampling frame and sample for analysis

LtL 2014 (W1) | LtL 2017 (W2) | LtL 2020 (W3) | LtL 2024 (W4) | |

Number of countries and semi-autonomous territories surveyed | 126 | 126 | 141 | 148 |

Sampling frame size (approximately) | 55,000 | 58,000 | 100,000 | 66,000 |

Successfully received the email (approximately) | 43,000 | 47,000 | 84,000 | 49,000 |

Respondents who answered any questions | 6,744 | 3,468 | 6,807 | 3,250 |

Response rate overall | 15.7% | 7.4% | 8.1% | 6.6% |

Respondents who answered questions about the influence or helpfulness of any development partner | 4,474 | 1,941 | 4,046 | 2,441 |

Response rate for influence/helpfulness module only | 10.4% | 4.1% | 4.8% | 5.0% |

Notes: The larger sampling frame in 2020 was due to the inclusion of parliamentarians.

Given imperfect information about the representativeness of our sample vis-à-vis the sampling frame, AidData mitigates potential bias in our surveys in three ways: (i) we develop a robust sampling frame of individuals who represent our target population of interest to ensure there is a large enough set of final respondents to facilitate this analysis; (ii) we collect data to monitor the demographics of those who receive an invitation versus those who respond to the survey to assess representativeness; and (iii) we use non-response weights when computing aggregate statistics (e.g., arithmetic means) from the survey results.

The LtL surveys offer comparability of responses for a common set of questions about perceptions of a large field of development partners across waves, between multiple cohorts of interest (e.g., sector, geography, gender), and using standardized scales. The sample size is sufficiently large to conduct descriptive trend analysis and test the explanatory power of donor-level, country-level, and individual factors that may shape leader perceptions. To facilitate these analyses, AidData leverages anonymized demographic information provided by the survey respondents (e.g., stakeholder group, [2] policy domain, country, education, work experience), along with secondary data sources for country attributes and development partner financial portfolios.

1.1.2 Which development partners?

In this report, we use development partners as an inclusive term to describe a range of external actors that provide an array of assistance to low- and middle-income countries—from financial assistance (e.g., grants and loans at varying degrees of concessionality) to technical assistance (e.g., advisory services and other non-financial support). A unique advantage of the LtL surveys, compared to agency-specific instruments or those limited to a subgroup of similar donors, is the opportunity to assess performance against a broad and diverse field of assistance suppliers, including bilateral and multilateral actors and traditional and non-traditional players.

In this last decade of disruption, countries have more choices of “non-traditional” development partners. South-South Cooperation providers, large and small, have expanded their bilateral assistance efforts and formed new multilateral agencies (Asmus et al., 2017; UN OSSC, 2024; Bhattacharya et al., 2025). Private philanthropies such as the Gates Foundation rival sovereign nations in the size of their grant-making (Burgess and Custer, 2023). [3] And international financial markets and private sector companies supply debt financing and management expertise for Global South leaders (Custer et al., 2023).

“Traditional” assistance providers, meanwhile, are experiencing disruption. The OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) club of advanced economies is experiencing populist movements and economic slowdowns, which create pressure to reduce aid budgets and consolidate agencies (Davies, 2025; Aly et al., 2024). Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom (UK) closed their independent aid agencies, integrating aid within their foreign ministries (Mathew and Custer, 2023). In early 2025, the United States (U.S.) dismantl ed its U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) (White House, 2025a and 2025b; Knickmeyer and Sherman, 2025). Multilaterals like the United Nations (UN) system and the World Bank (WB) see declining core contributions from advanced economies, shifting resources to issue-specific vertical funds, and mounting calls for reform (Hendra, 2024; OECD, 2024; G20, 2024).

AidData asks leaders to identify the development partners who had provided them with advice or assistance within the last five years before a survey was fielded (e.g., the 2024 survey asked about the 2020 to 2024 period) out of a list of 118 development partners, including 83 bilateral aid agencies, 32 multilateral development banks or intergovernmental organizations, and 3 private foundations. [4] In this report, we examine the performance of individual development partners against the full field of players, as well as compare each partner with those in their closest cohort group: traditional OECD bilaterals (e.g., Germany, Japan), traditional multilaterals (e.g., UN, WB), non-traditional bilaterals (e.g., China, Mexico), and non-traditional or Southern-led multilaterals (e.g., the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Islamic Development Bank).

Although a bilateral actor may be represented by more than one agency, in this report, we collapse the responses for all agencies flying the same flag into a single, unified picture for each perception measure. [5] For example, survey respondents could select up to four Japanese entities from which they had received advice or assistance: the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the Japanese embassy (or consulate-general), and the representative office of Japan. For the sake of simplicity, we collapse those responses into a single score for Japan in this report. This analysis only includes performance ratings for development partners rated by at least 30 respondents. To request more granular information and to compare multiple agencies representing the same bilateral player, please send inquiries to info@aiddata.org.

Table 2. Development partners with their acronyms, by cohort

Traditional Bilaterals + European Union (23)

Asia-Pacific:

- Australia (AUS)

- Japan (JPN)

- New Zealand (NZL)

- South Korea (KOR)

Europe and Eurasia:

- Austria (AUT)

- Belgium (BEL)

- Denmark (DNK)

- European Union (EU)

- Finland (FIN)

- France (FRA)

- Germany (DEU)

- Ireland (IRL)

- Italy (ITA)

- Luxembourg (LUX)

- Netherlands (NLD)

- Norway (NOR)

- Portugal (PRT)

- Spain (ESP)

- Sweden (SWE)

- Switzerland (CHE)

- United Kingdom (GBR

Western Hemisphere:

- Canada (CAN)

- United States (USA)

Traditional Multilaterals (23)

Global Development Banks:

- International Finance Corporation (IFC)

- International Monetary Fund (IMF)

- Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA)

- World Bank (WB)

Regional Development Banks:

- African Development Bank (AFDB)

- Asian Development Bank (ADB)

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD)

- Inter-American Development Bank (IDB)

United Nations System:

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

- International Labor Organization (ILO)

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP)

- United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA),

- United Nations Environment Program (UNEP)

- United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)

- World Food Program (WFP)

- World Health Organization (WHO)

Vertical Funds:

- GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance (GAVI)

- Green Climate Fund (GCF)

- Global Environment Facility (GEF)

- Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (GF)

Non-Traditional Bilaterals (15)

Asia-Pacific:

- China (CHN)

- India (IND)

- Taiwan (TWN)

Europe and Eurasia:

- Russia (RUS)

- Turkey (TUR)

Middle East & Africa:

- Israel (ISR)

- Kuwait (KWT)

- Libya (LBY)*

- Qatar (QAT)

- Saudi Arabia (SAU)

- South Africa (ZAF)

- United Arab Emirates (ARE)

Western Hemisphere:

- Brazil (BRA)

- Mexico (MEX)*

- Venezuela (VEN)*

Non-Traditional Multilaterals (8)

Asia-Pacific:

- Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB)

Middle East & Africa:

- Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (BADEA

- Arab Monetary Fund (AMF)

- Islamic Development Bank (ISDB)

- OPEC Fund for International Development (OFID)

Western Hemisphere:

- Caribbean Development Bank (CDB)

- Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI)

- Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean (CAF)

Private Foundations (2)

- Ford Foundation (FF),

- Gates Foundation (BMGF)

Notes: Asterisks (*) denote that these development partners had insufficient sample sizes to meet our threshold of 30 respondents and so they were not included in analyses of the influence and helpfulness performance measures.

1.1.3 How did leaders share their views, and on which topics?

Each Listening to Leaders survey contains two core modules related to development priorities and partner performance, which feature questions that are repeated from year to year to facilitate comparability over time. Additionally, we include several special topics modules that appear in certain years to drill down on timely areas of interest. In this report, we focus specifically on the questions that asked leaders about the development partners they work with and how they rate these partners against several performance dimensions. This series of questions remained relatively consistent across each wave, with a few exceptions described below. The full questionnaire for 2024 is available in the technical appendix accompanying the report.

Respondents were first asked to identify a particular “policy initiative” they worked on in the five years before the survey. [6] We defined policy initiative as an organizational action designed to solve a particular problem. Respondents were then presented with two preset lists, [7] one with multilateral organizations and private foundations, and the second with foreign embassies and bilateral agencies, and prompted to answer two questions:

- (i) Of the following intergovernmental organizations, development banks, and private foundations, which, if any, provided [you] with advice or assistance to support this initiative ;

- (ii) Of the following foreign embassies and bilateral agencies, which, if any, provided you with advice or assistance to support this initiative.

We use answers to these two questions to produce a perception-based measure of footprint: the percentage of leaders who reported receiving advice or assistance from a development partner within the last five years. This “footprint” measure gives us a baseline of a partner's reach or visibility with key constituencies in the Global South. In Chapter 2, we only assess trends in footprint between 2017 and 2024, due to differences in how the options for this question were presented to respondents in 2014 compared to other waves. [8]

Using footprint as a baseline of who was working with whom, respondents could rate their development partners on two performance dimensions: influence and helpfulness. We defined both concepts for respondents: “influence” was the power to change or affect the policy agenda, while “ helpfulness” was being of assistance in implementing policy changes. The 2014 survey used a 5-point rating scale, while subsequent surveys moved to a 4-point scale, so the first wave responses were rescaled to facilitate historical comparability across waves. [9] Specifically, respondents were asked to answer two questions about their development partners:

- “You indicated that the foreign and international organizations below provided [organization] with advice or assistance. How influential were they on [organization] decision to pursue this initiative? Respondents select among “not at all influential,” “only slightly influential,” “quite influential,” “very influential,” “don’t know/not sure,” and “prefer not to say.”

- “You indicated that the foreign and international organizations below provided [organization] with advice or assistance. How helpful were they on [organization] decision to pursue this initiative? Respondents select among “not at all helpful,” “only slightly helpful,” “quite helpful,” “very helpful,” “don’t know/not sure,” and “prefer not to say.”

Using the answers to these questions, we produced two perception-based performance measures. Influence—the percentage of leaders who viewed a given development partner as quite or very influential—is a barometer of an external actor’s agenda-setting ability in the early stages of the policymaking process to inform countries’ domestic priorities. Helpfulness—the percentage of leaders who viewed a given development partner as quite or very helpful—is a gauge of an external actor’s delivery capacity to support the design and implementation of policy changes in the later stages of the policymaking process. In this analysis, we only include partners if they were rated by at least 30 respondents in a given survey wave. Respondents also answered questions about what makes for an influential or helpful development partner. [10]

This report uses these perception-based measures to assess how individual development partners perform over time against themselves and relative to their peers. We provide a global overview at different points in time and assess the extent to which perceptions of development partners vary across different countries, stakeholders, and sectors. Since they were evaluated using the same questions and scales, we can rank each partner’s performance in relation to other agencies, based on who was deemed influential or helpful by the highest to lowest percentages of respondents.

In our analysis, we collapsed the 23 domains of policy expertise into seven larger sector groups: economic, environment, governance, infrastructure, rural development, social, and other. Country-level responses are organized into six larger regional groups: East Asia and the Pacific (EAP), Europe and Central Asia (ECA), Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), Middle East and North Africa (MENA), South Asia (SA), and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

With our introduction to the Listening to Leaders survey approach complete, the rest of the report is organized into four chapters:

- Chapter 2 (Footprint) analyzes from whom Global South leaders say they are receiving advice or assistance on development policy and how this is evolving over time.

- Chapter 3 (Performance) assesses how respondents rate the influence and helpfulness of their partners, considering how this varies across different years and leader types.

- Chapter 4 (Attraction) explores the factors that may shape leaders’ performance perceptions and what they look for in their preferred partners.

- Chapter 5 (Conclusion) reflects on how over ten years of Global South perceptions of development cooperation should inform how development partners approach the next decade.

2. Footprint: With whom are Global South leaders working?

The term development partner implies a degree of uniformity and stability in the agencies that supply advice or assistance. The opposite is true. Some variation is by design: agencies have different mandates, strategies, and resources to advance their missions. The priorities of taxpayers and shareholders play a role, as do the ambitions of allies and competitors. These constraints inform how bilateral agencies and multilateral organizations think about the countries, sectors, and types of leaders with which they want to work. At the same time, low- and middle-income countries also have a say in selecting development partners.

In this report, we use the LtL surveys to assess points of continuity and disruption in the composition of who is working with whom to advance development outcomes over a decade. In each survey wave, leaders identified which development partners (out of a list of bilateral and multilateral agencies) they had received advice or assistance from during the prior five-year period. As described in Chapter 1, we calculate the percentage of respondents who reported receiving advice or assistance from each development partner to measure that actor’s footprint.

In the remainder of this chapter, we provide a snapshot of who reported working with whom in 2024 (section 2.1) and compare how this has changed since 2017 (section 2.2). We highlight three key takeaways about the footprint of development cooperation over the past decade:

- Traditional multilaterals and OECD DAC bilaterals still worked with the most Global South leaders in 2024, proving durable in an age of expanded choice.

- Despite waning multilateralism, traditional multilaterals held steady or expanded their footprints, while many DAC bilaterals have lost ground since 2017.

- China remains the front-runner among non-traditional players, both bilateral and multilateral, and works with more leaders and countries, but this growth may be slowing.

2.1 The footprint of development cooperation in 2024

Global South leaders reported receiving advice or assistance from 71 bilateral and multilateral actors in the 2024 survey wave. Although it is not a performance measure, footprint provides important context to understand the size and diversity of each development partner’s constituency base. Smaller players have the luxury of brokering deep relationships and providing customized offerings. Larger players face trade-offs in going broad versus deep in their partnerships across the Global South. In Chapter 3, we will take a closer look at whether and how footprint corresponds with performance.

Finding #1. Traditional multilaterals and OECD DAC bilaterals still worked with the most Global South leaders in 2024, proving durable in an age of expanded choice

The 10 development partners with the largest footprints in 2024 worked with one-fifth or more of the leaders surveyed, spanning 119+ countries (Figure 2). UN agencies (e.g., UNDP, UNICEF, FAO, WHO) and international finance institutions (e.g., WB, IMF) dominated this group of global heavyweights. They were joined by bilaterals who historically had large assistance portfolios (e.g., U.S., Germany, Japan, EU). Impressively, these top footprint players were durable in their reach with leaders across geographic regions, [11] sectors, [12] and different stakeholder groups. [13] Conversely, the smallest footprint development partners worked with 1 percent or fewer of leaders. This included small South-South Cooperation providers (e.g., Libya, Venezuela, Mexico) and multilateral agencies (e.g., Central American Bank for Economic Integration, Arab Monetary Fund).

Figure 2. Top 10 largest development partners overall by perceived footprint, 2024

% respondents who said they received advice or assistance from a development partner between 2020 and 2024

Table scrolls horizontally

| Rank | Development Partner | Respondents per Partner | Percentage of All Survey Respondents | Number of Countries with at least One Respondent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WB | 1107 | 48.1 | 133 |

| 2 | UNDP | 1094 | 45.2 | 131 |

| 3 | EU | 970 | 40.9 | 131 |

| 4 | USA | 957 | 39.5 | 129 |

| 5 | UNICEF | 728 | 30.7 | 126 |

| 6 | WHO | 643 | 27.4 | 126 |

| 7 | IMF | 635 | 27.2 | 127 |

| 8 | DEU | 613 | 26.9 | 114 |

| 9 | JPN | 591 | 25.3 | 119 |

| 10 | FAO | 564 | 23.7 | 125 |

Notes: This figure shows the 10 development partners with the highest percentages of respondents who reported receiving advice or assistance from them between 2020 and 2024. The percentages take into account non-response weights. Sources: AidData’s 2024 Listening to Leaders Survey.

“Traditional multilaterals” refer to the UN system, the Bretton Woods institutions (the World Bank and International Monetary Fund) formed after World War II, “northern-led” regional development banks, [14] and vertical funds. The 23 traditional multilaterals tended to have the largest footprints, engaging with 17.9 percent of leaders and spanning 94 countries, on average. Large multilaterals, such as the World Bank (48 percent, 133 countries) and UNDP (45 percent, 131 countries), had expansive remits, working across geographies and sectors (see Figure 3 below). Smaller players included vertical funds—multi-stakeholder partnerships focusing on specific issues or themes (Gartner and Kharas, 2014), such as GAVI, which worked with roughly 6 percent of leaders from 62 countries.

Of course, a global snapshot can obscure the outsized importance of regionally or sectorally focused players. Four of five regional development banks assessed in this survey worked with one-fifth to one-third of the leaders from their respective focus regions. [15] Specialized UN agencies and vertical funds also had greater visibility with leaders in niche sectors and certain country types. UNEP and the GEF were among the largest players working with leaders who self-reported environmental expertise. IFAD and WFP were large players in the eyes of leaders with expertise in rural development. UNESCO, ILO, and UNFPA were among the top 10 multilateral players by footprint, working with social sector leaders. Focused on food security and reproductive health, agencies such as UNFPA and WFP also tended to be among the largest development partners for leaders from low-income and fragile states.

Figure 3. Perceived footprint of traditional multilaterals as a cohort, 2024 snapshot

% respondents who said they received advice or assistance from a traditional multilateral between 2020 and 2024

Table scrolls horizontally

| Rank | Development Partner | Respondents per Partner | Percentage of All Survey Respondents | Number of Countries with at least One Respondent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WB | 1107 | 48.1 | 133 |

| 2 | UNDP | 1094 | 45.2 | 131 |

| 3 | UNICEF | 728 | 30.7 | 126 |

| 4 | WHO | 643 | 27.4 | 126 |

| 5 | IMF | 635 | 27.2 | 127 |

| 6 | FAO | 564 | 23.7 | 125 |

| 7 | UNESCO | 475 | 19.4 | 122 |

| 8 | ILO | 452 | 19.1 | 113 |

| 9 | UNFPA | 423 | 17.2 | 114 |

| 10 | AFDB | 385 | 17.0 | 62 |

| 10 | WFP | 416 | 17.0 | 103 |

| 12 | ADB | 345 | 14.8 | 60 |

| 13 | UNEP | 340 | 14.6 | 110 |

| 14 | UNAIDS | 290 | 12.3 | 98 |

| 15 | GEF | 308 | 12.2 | 103 |

| 15 | IFAD | 304 | 12.2 | 96 |

| 17 | GCF | 286 | 11.7 | 102 |

| 18 | IFC | 203 | 8.7 | 81 |

| 19 | EBRD | 155 | 8.6 | 42 |

| 20 | GF | 201 | 8.2 | 83 |

| 21 | IDB | 250 | 7.8 | 40 |

| 22 | GAVI | 140 | 5.8 | 62 |

| 23 | MIGA | 42 | 1.8 | 30 |

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of respondents who reported receiving advice or assistance from a traditional multilateral between 2020 and 2024. Only development partners with a sample size of 30 respondents or more are included in this visual. The percentages also take into account non-response weights. Sources: AidData’s 2024 Listening to Leaders Survey.

“Traditional bilaterals” refer to member countries of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee. [16] On average, the 23 traditional bilaterals assessed in the survey had the second-largest footprint of the four donor groups, engaging on average with 13.1 percent of leaders from 72 countries. [17] Although these traditional bilaterals adhere to a common set of OECD principles and standards for their assistance efforts, they are highly diverse in their footprint (Figure 4). As of 2024, one-quarter or more of leaders surveyed reported receiving advice or assistance from larger footprint players like the EU (41 percent, 131 countries), the U.S. (40 percent, 129 countries), Germany (27 percent, 114 countries), and Japan (25 percent, 119 countries). It is important to underscore that this survey predates the closure of the U.S. Agency for International Development and cuts to U.S. foreign aid programs announced in early 2025.

Some mid-sized traditional bilaterals have achieved outsized footprints with leaders from select geographic regions, country types, or focus sectors. Canada, Sweden, Australia, and Switzerland, for example, each supplied advice or assistance to only 12 to 13 percent of leaders surveyed globally. However, all four of these bilaterals were among the top 10 largest players by footprint in at least one geographic region. [18] Australia’s proximity to low-lying Pacific island nations likely explains its appearance among the top 10 largest footprint donors with leaders from small island states (SIDS). Small traditional bilaterals like Finland and Portugal worked with 3 percent or fewer leaders from 38 and 21 countries, respectively.

Figure 4. Perceived footprint of traditional bilaterals as a cohort, 2024 snapshot

% respondents who said they received advice or assistance from a traditional bilateral between 2020 and 2024

Table scrolls horizontally

| Rank | Development Partner | Respondents per Partner | Percentage of All Survey Respondents | Number of Countries with at least One Respondent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EU | 970 | 40.9 | 131 |

| 2 | USA | 957 | 39.5 | 129 |

| 3 | DEU | 613 | 26.9 | 114 |

| 4 | JPN | 591 | 25.3 | 119 |

| 5 | GBR | 429 | 18.2 | 104 |

| 6 | FRA | 384 | 17.2 | 100 |

| 7 | NLD | 391 | 16.6 | 87 |

| 8 | CAN | 316 | 13.1 | 93 |

| 9 | SWE | 316 | 12.7 | 64 |

| 10 | AUS | 293 | 12.0 | 60 |

| 11 | NOR | 272 | 11.6 | 77 |

| 12 | CHE | 282 | 11.5 | 81 |

| 13 | KOR | 242 | 10.5 | 88 |

| 14 | DNK | 161 | 6.7 | 57 |

| 15 | ESP | 168 | 6.2 | 56 |

| 16 | BEL | 152 | 6.1 | 50 |

| 17 | AUT | 112 | 5.1 | 40 |

| 18 | NZL | 138 | 5.0 | 33 |

| 19 | ITA | 69 | 3.6 | 43 |

| 20 | IRL | 82 | 3.3 | 39 |

| 20 | LUX | 80 | 3.3 | 34 |

| 22 | FIN | 72 | 3.0 | 38 |

| 23 | PRT | 61 | 2.1 | 21 |

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of respondents who reported receiving advice or assistance from a traditional bilateral during the period from 2020 to 2024. Percentages of respondents also take into account non-response weights. Sources: AidData’s 2024 Listening to Leaders Survey.

Non-traditional bilaterals operate outside of the OECD DAC group, including, but not limited to, donors who position their assistance as South-South Cooperation between low- and middle-income countries (UN DESA, 2019). On average, the 15 non-traditional bilaterals assessed in the survey had a much smaller footprint than their traditional peers, engaging with 3.6 percent of leaders from 40 countries. China was the elephant in the room, working with 14.4 percent of leaders across 97 countries (Figure 5) and ranking 21st among all development partners, the only non-traditional player in the top 25 development partners by footprint. Emerging contenders include India (6.2 percent, 61 countries) and Turkey (5.6 percent, 58 countries), while the remainder of the non-traditional bilaterals worked with 4 percent or fewer leaders surveyed.

Non-traditional multilaterals have the smallest footprint as a group: the eight players assessed in the survey engaged with 2.4 percent of leaders from 26 countries, on average. On the upper end, the Islamic Development Bank (ISDB) worked with nearly 6 percent of the sample, and the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (BADEA) worked with 3 percent (Figure 6). On the lower end, some non-traditional multilaterals worked with 1.5 percent or fewer of the leaders surveyed. For example, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) was a relatively small player, with only 1.4 percent of respondents from 22 countries reportedly receiving its advice or assistance.

Figure 5. Perceived footprint of non-traditional bilaterals as a cohort, 2024 snapshot

% respondents who said they received advice or assistance from a non-traditional bilateral between 2020 and 2024

Table scrolls horizontally

| Rank | Development Partner | Respondents per Partner | Percentage of All Survey Respondents | Number of Countries with at least One Respondent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CHN | 338 | 14.4 | 97 |

| 2 | IND | 150 | 6.2 | 61 |

| 3 | TUR | 122 | 5.6 | 58 |

| 4 | ARE | 85 | 3.9 | 48 |

| 5 | BRA | 93 | 3.8 | 48 |

| 6 | SAU | 84 | 3.5 | 53 |

| 7 | KWT | 78 | 3.2 | 40 |

| 8 | QAT | 66 | 2.7 | 44 |

| 8 | TWN | 67 | 2.7 | 29 |

| 10 | RUS | 55 | 2.4 | 37 |

| 11 | ZAF | 46 | 2.2 | 28 |

| 12 | ISR | 40 | 1.7 | 27 |

| 13 | MEX | 24 | 0.7 | 13 |

| 13 | VEN | 18 | 0.7 | 14 |

| 15 | LBY | 9 | 0.3 | 9 |

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of respondents who reported receiving advice or assistance from a nontraditional bilateral during the period from 2020 to 2024. Percentages also take into account non-response weights. Sources: AidData’s 2024 Listening to Leaders Survey.

Figure 6. Perceived footprint of non-traditional multilaterals as a cohort, 2024 snapshot

% respondents who said they received advice or assistance from a non-traditional multilateral between 2020 and 2024

Table scrolls horizontally

| Rank | Development Partner | Respondents per Partner | Percentage of All Survey Respondents | Number of Countries with at least One Respondent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ISDB | 127 | 5.7 | 43 |

| 2 | BADEA | 78 | 3.3 | 36 |

| 3 | OFID | 63 | 2.5 | 44 |

| 4 | CDB | 59 | 2.2 | 15 |

| 5 | CAF | 71 | 2.0 | 20 |

| 6 | AIIB | 28 | 1.4 | 22 |

| 7 | AMF | 20 | 1.0 | 16 |

| 8 | CABEI | 31 | 0.9 | 9 |

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of respondents who reported receiving advice or assistance from a nontraditional multilateral during the period from 2020 to 2024. Percentages also take into account non-response weights. Sources: AidData’s 2024 Listening to Leaders Survey.

2.2 Changes over time in the footprint of development cooperation

The landscape of development cooperation is constantly evolving: new agencies form, some consolidate, and others broaden or narrow their focus sectors and geographies. How might these geopolitical dynamics change the footprint of development cooperation? The largest footprint partners—UN agencies, global international finance institutions, and several OECD DAC bilaterals—remained fairly consistent between each survey wave.

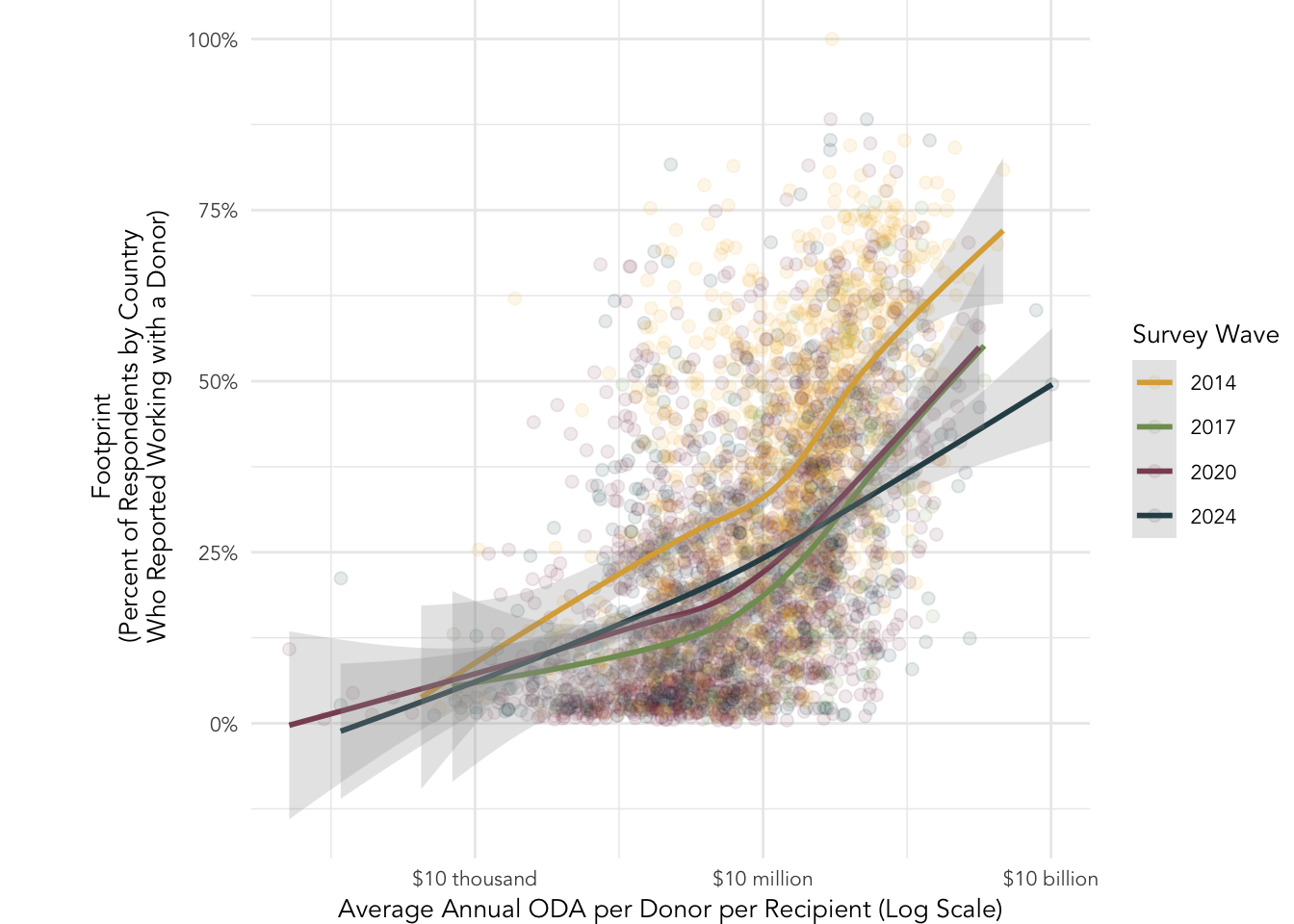

Development partners with larger pocketbooks tend to work with a greater percentage of leaders surveyed. However, money is not deterministic of footprint, and this is even less the case now than in earlier years. Although the size of a donor’s development finance portfolio and its footprint in a given recipient country remain positively correlated, the magnitude of this relationship has waned since 2017. [19] In other words, more money was less strongly linked to a large footprint in 2024 than in 2017 (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Perceived footprint and mean official development assistance, traditional bilaterals and multilaterals only, 2014-2024 period

Notes: This scatterplot visualizes the relationship between footprint (the percentage of those who reported receiving advice or assistance from a given traditional bilateral) by recipient country across each of the four survey waves and the official development assistance disbursements of those players (log of mean ODA flows for 2014-2023). The percentages of respondents take into account non-response weights. Average annual ODA was calculated using three years of reported disbursements prior to each survey wave. Sources: AidData’s Listening to Leaders Survey (2014-2024).

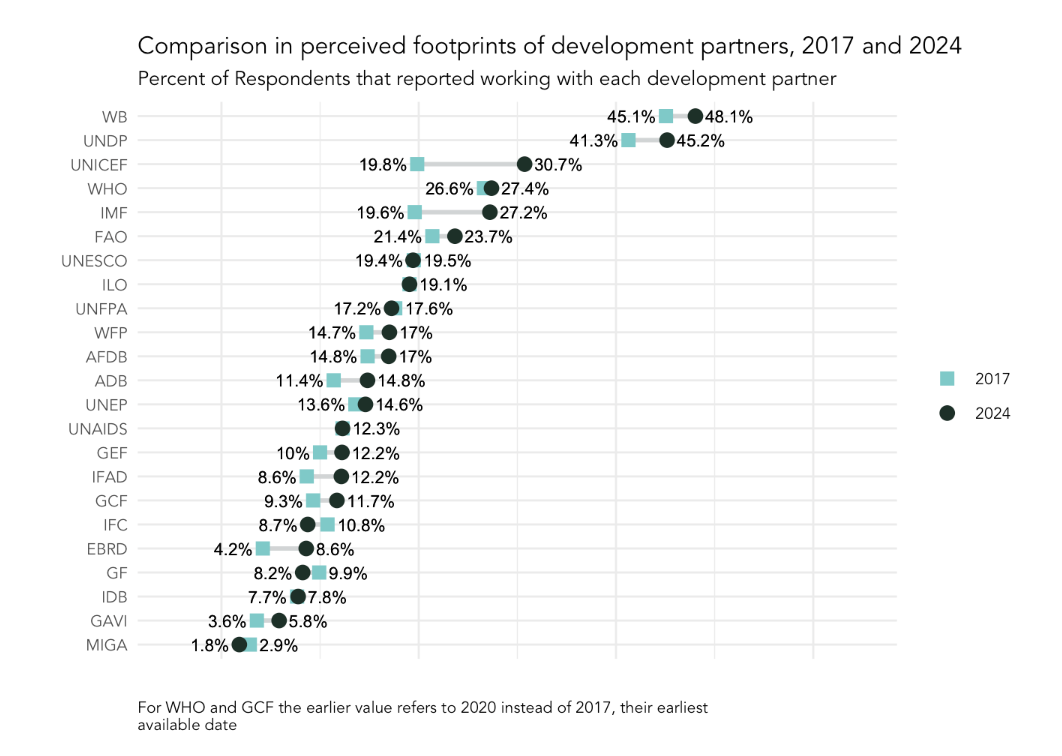

Finding #2. Despite waning multilateralism, traditional multilaterals held steady or expanded their footprints, while many DAC bilaterals have lost ground since 2017

Most traditional multilaterals held steady or saw their footprints expand by 2 to 3 percentage points among leaders surveyed over the period (Figure 8). The largest increases were with leaders who reported receiving advice or support from UNICEF (+10.9 percentage points) and the IMF (+7.6 percentage points). This sharp uptick may coincide with growing demands to help countries navigate instability from conflict and emergencies (e.g., UNICEF’s expanding humanitarian assistance portfolio) or fiscal and monetary crises (e.g., the IMF’s role in resolving a wave of debt distress and defaults).

Figure 8. Change in footprint, traditional multilaterals, 2017 to 2024

Percentage of respondents who reported working with each traditional multilateral in 2017 and 2024

Notes: Traditional multilaterals are ordered from the largest to the smallest overall footprints, according to the percentage of respondents who reported working with them in AidData’s LtL surveys in 2017 and 2024. Only partners with at least 30 responses in both survey waves are listed. For WHO and GCF, the earlier value refers to 2020 instead of 2017, their earliest available date. Sources: AidData’s Listening to Leaders Survey (2017 - 2024).

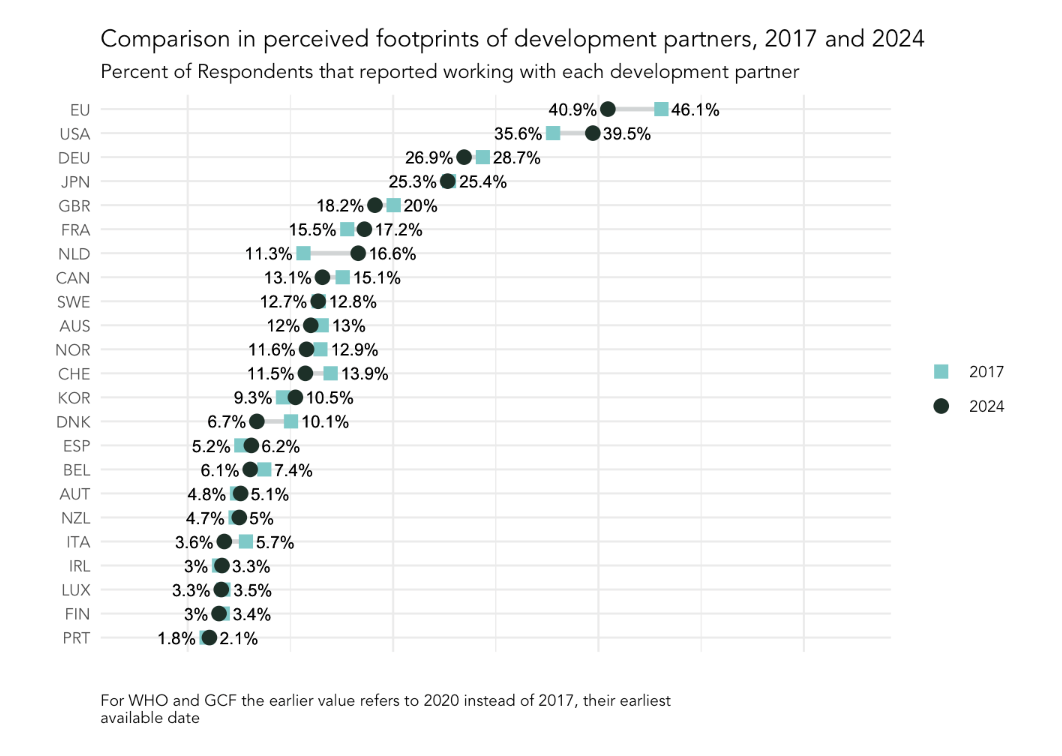

The footprints of traditional bilaterals have generally held steady or contracted by 1 to 2 percentage points since 2017 (Figure 9). For development partners like the United Kingdom (UK) and Canada, whose footprints decreased by roughly two percentage points, these contractions may align with policy shifts such as aid cuts or consolidation of aid agencies into foreign ministries (Krutikova and Warwick, 2017; Worley, 2020; Carmen and Calleja, 2013; Troilo, 2015). The EU, Denmark, Switzerland, and Germany also saw their footprints decline by 2 to 5 percentage points.

Figure 9. Change in footprint, traditional bilaterals, 2017 to 2024

Percentage of respondents who reported working with each traditional bilateral in 2017 and 2024

Notes: Traditional bilaterals are ordered from the largest to the smallest overall footprints, according to the percentage of respondents who reported working with them in AidData’s LtL surveys in 2017 and 2024. Only partners with at least 30 responses in both survey waves are listed. Sources: AidData’s Listening to Leaders Survey (2017 - 2024).

Exceptions to this trend of declining reach among traditional bilaterals were the Netherlands, the U.S., and France, whose footprints grew between 2017 and 2024 by 2 to 5 percentage points. In this period, the U.S. and France shared an interest in working with states experiencing crises, conflicts, or emergencies. Humanitarian assistance has accounted for a growing share of U.S. development assistance over the last decade (Custer, 2024), and overcoming root causes of insecurity in fragile states was a French priority to curb migration pressures (OECD, 2018 and 2023). It is unclear whether this focus may explain the uptick in their footprints.

However, these donors are more likely than not to see reduced footprints in future years. France and the Netherlands announced substantial cuts to their aid budgets for 2025 (Donor Tracker, 2024a and 2024b). The U.S. is engaged in a far-reaching overhaul of its development assistance architecture (Custer et al., 2025). These are just a few of the traditional bilaterals that have recently announced reductions in their development cooperation (Table 3).

Table 3. Historical ODA (2023) and announced aid budget cuts by selected traditional bilaterals

Select DAC countries | Total ODA in 2023 | Announced aid budget reductions in 2024 and 2025 |

|---|---|---|

Belgium | $2.81 billion | The government a nnounced a planned 25 % reduction in development cooperation. |

Finland | $1.59 billion | The government plans to reduce ODA by roughly 25% between 2024 and 2027. |

France | $15.1 billion | The 2025 draft budget cuts core ODA by €1.3 billion (a 23 % drop from 2024), following a smaller cut of about €1 billion, which was already implemented in 2024. |

Germany | $37.9 billion | The government reduced ODA by nearly €2 billion in 2024, compared to 2023 levels, and plans to slash a cumulative €4.8 billion from development and humanitarian spending by 2025. |

Netherlands | $7.4 billion | The government announced in late 2024 that it would cut ODA by over two-thirds over three years, reducing the budget by a total of €2.4 billion by 2027. |

Norway | $5.6 billion | The 2024 budget proposal reduced ODA by 5 %, or $460 million. |

Sweden | $5.6 billion | The government a nnounced a 5 % reduction in ODA, abandoning commitments to 1% of GNI. |

UK | $19.1 billion | The government a nnounced that it will drop ODA to 0.3% of GNI (from 0.5%), equating to roughly a 40 % reduction in the aid budget. |

U.S. | $63.7 b illion | In 2025, the government eliminated 90 % of USAID's foreign aid contracts, cancelled 83 % of assistance programs, and reduced USAID staff from 10,000 to 15 positions. |

Sources: OECD (2023b, 2024b), Donor Tracker (2024a-b, 2025), Meijer (2024), Gulrajani and Pudussery (2025), Belga (2025), MacKinnon (2024), Knickmeyer et al., (2025), Mitchell and Hughes (2025), Hird (2025), GoN. (2025), Craig (2025), Demirjian et al., (2025).

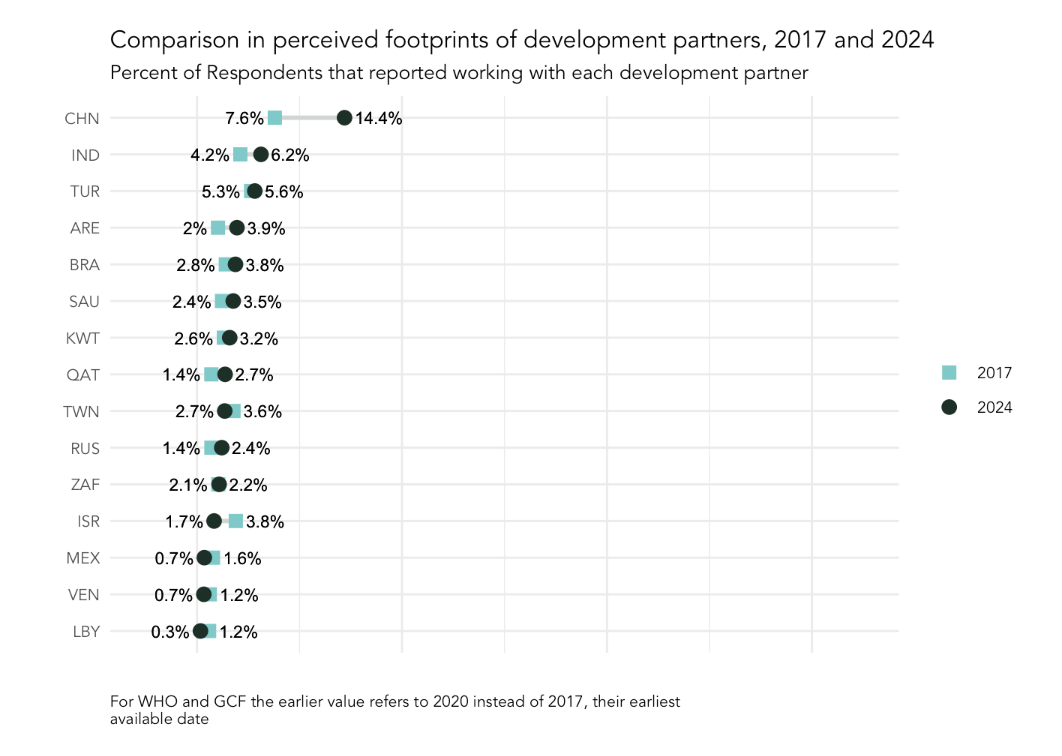

Finding #3. China remains the front-runner among non-traditional players, both bilateral and multilateral, and works with more leaders and countries, but this growth may be slowing

Non-traditional bilaterals generally grew their footprints over the period, albeit at modest levels (Figure 10). China was in a league of its own: Beijing increased its footprint by 6.8 percentage points between 2017 and 2024, equivalent to an 89 percent change. Most of this expansion occurred between 2017 and 2020, as Beijing enthusiastically promoted President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (Horigoshi et al., 2022).

By 2024, China’s absolute footprint was roughly similar to Canada and the Asian Development Bank (ADB). Nevertheless, relative to earlier years, China’s growth spurt tapered off between 2020 and 2024. This slowdown could reflect a lower risk tolerance in Beijing for supplying additional debt financing and a higher reticence among countries to sign on to projects, amid a wave of defaults in China’s borrowers (Parks et al., 2023). [20]

Figure 10. Change in footprint, non-traditional bilaterals, 2017 to 2024

Percentage of respondents who reported working with each nontraditional bilateral in 2017 and 2024

Notes: Nontraditional bilaterals are ordered from the largest to the smallest overall footprints, according to the percentage of respondents who reported working with them in AidData’s LtL surveys in 2017 and 2024. Only partners with at least 30 responses in both survey waves are listed. Sources: AidData’s Listening to Leaders Survey (2017 - 2024).

India, a fellow BRICS member and a close competitor of China, also enlarged its footprint by 2 percentage points, roughly a 50 percent change, since 2017. New Delhi has made no secret of the fact that India sees its development cooperation efforts through a strategic lens of opening up market access for Indian firms to compete with Chinese state-owned enterprises, curbing Beijing’s influence in South Asia, and securing access to energy resources and other critical supply chains (Mathur, 2021; Singh, 2022). Finally, non-traditional multilaterals grew their footprints over the period, though the differences were largely within 1 percentage point or less.

3. Performance: How do leaders rate development partners?

Leaders are not monolithic in their preferences. Development partners may have differing areas of comparative advantage and disadvantage in an increasingly crowded marketplace. Once reliable standard bearers for aid programs, G7 economies are increasingly reluctant to expend political capital and taxpayer funds to support social-economic progress in other countries. [21] UN and international finance institutions, long-standing venues for multilateral cooperation, seek to overcome a perceived “legitimacy deficit,” reduced core support, and calls for reforms (Custer et al., 2025; Gulrajani and Lundsgaarde, 2023; Graham, 2024). [22] Once “recipients” of aid, non-traditional bilaterals also supply assistance to other countries (Aly et al., 2024).

This raises a critical question: in an age of expanded choice, how do Global South leaders evaluate the development partners from whom they receive advice or assistance? The Listening to Leaders Survey considers two perception-based measures of partner performance: (i) influence in shaping how leaders prioritize which problems to solve (i.e., agenda-setting); and (ii) helpfulness in supporting leaders to implement policy changes (i.e., reform implementation). Respondents could rate each development partner they had worked with during a five-year period on a scale of 1 (not at all influential/not at all helpful) to 4 (very influential/very helpful).

In the remainder of this chapter, we first provide a snapshot of partner performance as of 2024 (section 3.1) and then compare how this has changed over the last decade (section 3.2). We highlight three takeaways about the performance of development partners over the decade:

- Non-traditional players have not yet displaced traditional multilaterals and OECD DAC bilaterals, who still dominated the leaderboard on influence and helpfulness in 2024

- BRICS and Middle Eastern development partners were among the most improved, charting big performance gains over the decade, but still lagging traditional players

3.1 The perceived performance of development partners in 2024

Global South leaders generally viewed their development partners favorably. In 2024, the average development partner was rated as influential by roughly three-quarters (72.4 percent) of the leaders they worked with and helpful by four-fifths (81.8 percent) of this group. However, averages can obscure attitudes towards specific partners. There was a 37 percentage point difference between the most and least influential development partners, the Global Fund (92.1 percent) and Brazil (55.1 percent), in 2024. That year, there was a gap of 29 percentage points between the most and least helpful partners, Portugal (96 percent) and Qatar (67 percent).

3.1.1 Global heavyweights: Top performers across geographies and sectors

Eighty-four percent or more of leaders who worked with the top 10 influencers in 2024 said these partners were quite or very influential in shaping their domestic priorities (Figure 11). International finance institutions (e.g., IMF, WB, EBRD) and health-focused agencies (such as the Global Fund, GAVI, and WHO) were among the top influencers. The U.S. and the EU, historically large bilateral assistance suppliers, were considered to be highly influential. Nevertheless, New Zealand and Portugal stand out as top influencers despite smaller footprints and budgets relative to their peers.

In 2024, many top helpers were also highly influential, with some exceptions (Figure 12). More than 88 percent of leaders who worked with the top 10 helpers rated them quite or very helpful. UN agencies (e.g., UNICEF, WHO, and UNDP) and vertical funds (e.g., Global Fund and GAVI) performed well, as did the World Bank. Bigger bilateral players like the U.S. and the EU scored high marks on helpfulness, but so too did smaller peers like New Zealand and Portugal. Above-average performers on influence [23] and helpfulness [24] shared several commonalities. They were more likely to be traditional multilaterals or DAC bilaterals, long-standing suppliers of development finance at scale, and previously rated as above-average performers in prior survey waves.

Figure 11. Top 10 most influential development partners overall, 2024

% respondents who rated a development partner they worked with as quite or very influential

Table scrolls horizontally

| Rank | Development Partner | Respondents per Partner | Percentage of All Survey Respondents | Number of Countries with at least One Respondent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GF | 166 | 92.1 | 76 |

| 2 | IMF | 502 | 89.4 | 120 |

| 3 | WB | 887 | 88.4 | 130 |

| 4 | NZL | 107 | 87.3 | 23 |

| 5 | USA | 768 | 86.5 | 122 |

| 6 | GAVI | 99 | 86.1 | 52 |

| 7 | EU | 761 | 85.7 | 125 |

| 8 | WHO | 489 | 85.5 | 122 |

| 9 | EBRD | 117 | 84.2 | 34 |

| 10 | PRT | 45 | 83.7 | 17 |

Notes: This figure shows the 10 development partners rated as quite or very influential by the highest percentage of respondents in 2024 who reported receiving advice or assistance from them. Percentages take into account non-response weights. Sources: AidData’s 2024 Listening to Leaders Survey.

Figure 12. Top 10 most helpful development partners overall, 2024

% respondents who rated a development partner they worked with as quite or very helpful

Table scrolls horizontally

| Rank | Development Partner | Respondents per Partner | Percentage of All Survey Respondents | Number of Countries with at least One Respondent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PRT | 49 | 96.0 | 18 |

| 2 | GF | 164 | 94.0 | 78 |

| 3 | GAVI | 102 | 92.9 | 51 |

| 4 | NZL | 109 | 91.3 | 24 |

| 5 | UNICEF | 576 | 90.6 | 125 |

| 6 | WHO | 507 | 89.5 | 123 |

| 7 | EU | 758 | 89.3 | 129 |

| 8 | USA | 748 | 89.1 | 124 |

| 9 | WB | 853 | 88.8 | 127 |

| 10 | UNDP | 848 | 88.6 | 129 |

Notes: This figure shows the 10 development partners rated as quite or very helpful by the highest percentage of respondents in 2024 who reported receiving advice or assistance from them. Percentages take into account non-response weights. Sources: AidData’s 2024 Listening to Leaders Survey.

Finding #4. Non-traditional players have not yet displaced traditional multilaterals and OECD DAC bilaterals, who still dominated the leaderboard on influence and helpfulness in 2024

Overall, the 23 traditional multilaterals outperformed other groups. On average, approximately 79 percent of leaders who worked with a traditional multilateral rated that actor as influential, and 86 percent considered it helpful. That said, not all multilaterals are seen in the same vein. There was a 22.3 percentage point difference between the most influential (Global Fund, 92.1 percent) and the least influential (International Fund for Agricultural Development, 69.8 percent). There was a similar margin of difference (19.1 percentage points) between the most and least helpful traditional multilateral—the Global Fund (94.0 percent) and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (79.4 percent).

The 23 traditional bilaterals were also well regarded. Seventy-two percent of leaders who worked with these actors thought they were influential, on average. Eighty-three percent found them to be helpful. Nonetheless, leaders see differences between traditional bilaterals, even if they theoretically espouse similar aid effectiveness practices through their membership in the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee. There was a sizable gap between traditional bilaterals at the top and bottom of the leaderboard on influence (26.7 percentage points) [25] and helpfulness (24.7 percentage points). [26]

The geopolitical clout of a foreign government, going beyond aid to encompass other tools of economic statecraft and security cooperation, could amplify the influence of more politically powerful players like the U.S., the EU, and Germany, among the most influential of the traditional bilaterals. Middle powers like Spain and the Netherlands had greater variability in the degree to which they were seen to influence policy priorities and help implement reforms. Smaller development partners like New Zealand and Portugal outperformed larger players like Canada and Italy, for example.

Non-traditional bilaterals and multilaterals have not yet displaced the apparent dominance of traditional development partners. Less than 70 percent of leaders who worked with the average non-traditional bilateral or multilateral considered them influential (67 and 62 percent, respectively). The results were marginally better for helpfulness: roughly three-quarters of leaders rated these actors as helpful, on average. Non-traditional multilaterals were viewed more uniformly, with the narrowest gaps of any group between the top and bottom performers (12.2 percentage points for influence, 15.3 percentage points for helpfulness). [27]

A handful of emerging bilaterals were able to buck these trends. South Africa (13th), China (24th), India (29th), and Taiwan (33rd) placed among the 35 above-average influencers. Saudi Arabia (23rd) and Taiwan (36th) were the top emerging bilaterals on helpfulness. To achieve this feat, these emerging players leapfrogged traditional DAC bilaterals, including Nordic countries (e.g., Finland, Norway, and Denmark) and other European development partners (e.g., Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Italy). Comparatively, other non-traditional bilaterals such as Brazil (55 percent influential, 67.1 percent helpful) and Qatar (55.3 percent influential, 67 percent helpful) were less able to break through in a crowded marketplace.

3.1.2 Specialized star power: Niche areas of comparative advantage

Some development partners are truly global heavyweights: they consistently appear in the top 10 performers across multiple regions and sectors. This elite group included traditional multilateral organizations (the World Bank, IMF, UNICEF, UNDP, and WHO), along with large DAC bilaterals such as the U.S., the EU, and Germany. [28] Other development partners demonstrated specialized star power, receiving high marks in certain regions, sectors, or country types.

Geographic proximity, linguistic similarity, and concentration of finances could explain some variation in development partners’ comparative advantage. In East Asia and the Pacific, top performers included regional powers like New Zealand, Japan, Australia, China, and South Korea (Figures 13 and 14). [29] Sharing a common language and history via former colonial ties with the region’s Portuguese-speaking countries, Portugal was among the top 10 influencers and helpers in Sub-Saharan Africa. [30] India and Spain were top performers with leaders from their respective focus regions of South Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean. [31] Germany and the UK were well-regarded by leaders from Europe and Central Asia. [32]