How China Lends: A Rare Look into 100 Debt Contracts with Foreign Governments

Abstract

China is the world's largest official creditor, but we lack basic facts about the terms and conditions of its lending. Very few contracts between Chinese lenders and their government borrowers have ever been published or studied. This paper is the first systematic analysis of the legal terms of China's foreign lending. We collect and analyze 100 contracts between Chinese state-owned entities and government borrowers in 24 developing countries in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Oceania, and compare them with those of other bilateral, multilateral, and commercial creditors. Three main insights emerge. First, the Chinese contracts contain unusual confidentiality clauses that bar borrowers from revealing the terms or even the existence of the debt. Second, Chinese lenders seek advantage over other creditors, using collateral arrangements such as lender-controlled revenue accounts and promises to keep the debt out of collective restructuring (“no Paris Club” clauses). Third, cancellation, acceleration, and stabilization clauses in Chinese contracts potentially allow the lenders to influence debtors’ domestic and foreign policies. Even if these terms were unenforceable in court, the mix of confidentiality, seniority, and policy influence could limit the sovereign debtor’s crisis management options and complicate debt renegotiation. Overall, the contracts use creative design to manage credit risks and overcome enforcement hurdles, presenting China as a muscular and commercially-savvy lender to the developing world.

Acknowledgements

We thank Olivier Blanchard, Lee Buchheit, Guy-Uriel Charles, Mitu Gulati, Patrick Honohan, Nicholas Lardy, Adnan Mazarei, Carmen M. Reinhart, Arvind Subramanian, Edwin M. Truman, Jeromin Zettelmeyer, two anonymous reviewers, and the participants in a March 2021 workshop at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) for comments on an earlier version of this paper. We thank Eva Zhang from the Peterson Institute for International Economics for reviewing our data and replicating our analysis, as well as John Custer, Parker Kim, and Soren Patterson from AidData for copy-editing, formatting, and graphic design of the final publication. We also owe a debt of gratitude to the large team of research assistants (RAs)—including Aiden Daly, Alex McElya, Amelia Grossman, Andrew Brennan, Andrew Tanner, Anna East, Arushi Aggarwal, Bat-Enkh Baatarkhuu, Beneva Davies-Nyandebo, Carina Bilger, Carlos Hoden-Villars, Caroline Duckworth, Caroline Morin, Catherine Pompe van Meerdervoort, Cathy Zhao, Celeste Campos, Chifang Yao, Christian Moore, Claire SchlickClaire Wyszynski, Connor Sughrue, Dan Vinton, David(Joey) Lindsay, Eileen Dinn, Elizabeth Fix, ElizabethPokol, Emma Codd, Emmi Burke, Erica Stephan, Fathia Dawodu, Florence Noorinejad,Gabrielle Ramirez, Georgiana Reece, Grace Klopp, Haley VanOverbeck,Han (Harry) Lin, Hannah Slevin, HarinOk, Isabel Ahlers, Jack Mackey, JiaxinTang, Jiaying Chen, Jim Lambert, JingyangWang, Jinyang Liu, John Jessen, Johnny Willing, Jordan Metoyer, Julia Tan, Julian Allison, Lukas Franz, Kacie Leidwinger, Kathryn Yang, Kathryn Ziccarelli, Kathrynn Weilacher, Kieffer Gilman Strickland, Kiran Rachamallu, Leslie Davis, Linda Ma, Lydia Vlasto, Marty Kibiswa, Mary Trotto, Mattis Boes, Maya Priestley, Mengting Lei, Mihika Singh, Molly Charles, Natalie Larsen, Natalie White, Olivia Le Menestrel, Olivia Yang, Paige Groome, Paige Jacobson, Patrick Loeffler, Pooja Tanjore, Qier Tan, Raul De La Guardia, Richard Robles, Rodrigo Arias, Rory Fedorochko, Ryan Harper, Sam LeBlanc, Samantha Rofman, Sania Shahid, Sarah Farney, Sariah Harmer, Sasan Faraj, Sebastian Ruiz, Shannon Dutchie, Shishuo Liu, Sihan (Brigham)Yang, Solange Umuhoza, Steven Pressendo, Taige Wang, Tasneem Tamanna Amin, Thai-Binh Elston, Undra Tsend, Victoria Haver, Wassim Mukayed, Wenyang Pan, Wenye Qiu, Wenzhi Pan, Williams Perez-Merida, Xiangdi William Wu, Xiaofan Han, Xinxin (Cynthia) Geng, Xinyao Wang, Xinyue Pang, Xuejia (Stella) Tong, Xufeng Liu, Yannira Lopez Perez, Yian Zhou, Yiling (Elaine) Zhang, Yiwen Sun, Youjin Lee, Yunhong Bao, Yunji Shi, Yunjie Zhang, Yuxin (Susan) Shang, Zihui Tian, Ziqi Zheng, Ziyi (Zoey) Jin, and Ziyi Fu—who helped identify, retrieve, and code the loan contracts in this study. We also received excellent project and data management support from Brooke Russell, Joyce Jiahui Lin, Katherine Walsh, Kyra Solomon, Lincoln Zaleski, Mengfan Cheng, Sheng Zhang, and Siddhartha Ghose.

This study was made possible with generous financial support from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), and Georgetown University Law Center. We also acknowledge that it was indirectly made possible through a cooperative agreement (AID-OAA-A-12-00096) between USAID's Global Development Lab and AidData at the College of William and Mary under the Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) Program. Sebastian Horn and Christoph Trebesch gratefully acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) under the Priority Programme SPP 1859. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Ford Foundation, USAID, FCDO, the United States Government, or the Government of the United Kingdom.

Section 1 Introduction

The Chinese government and its state-owned banks have lent record amounts to governments in lowand middle-income countries since the early 2000s, making China the world’s largest official creditor. Although several recent studies examine the economics of Chinese lending, we still lack basic facts about how China and its state-owned entities lend—in particular, how the loan contracts are written and what terms and conditions they contain. [1] Neither Chinese creditors nor their sovereign debtors normally disclose the text of their loan agreements. But the legal and financial details in these agreements have gained relevance in the wake of the Covid-19 shock and the growing risks of financial distress in countries heavily indebted to Chinese lenders. [2] In light of the high stakes, the terms and conditions of China’s debt contracts have become a matter of global public interest.

China's loan agreements—sight unseen—are the subject of intense debate and controversy. Some have suggested that Beijing is deliberately pursuing “debt trap diplomacy,” imposing harsh terms on its government counterparties and writing contracts that allow it to seize strategic assets when debtor countries run into financial problems (e.g., Chellaney 2017; Moody's 2018; Parker and Chefitz 2018). Senior U.S. government officials have argued that Beijing “encourages dependency using opaque contracts […] that mire nations in debt and undercut their sovereignty” (Tillerson 2018). At the opposite end of the spectrum, others have emphasized the benefits of China's lending and suggested that concerns about harsh terms and a loss of sovereignty are greatly exaggerated (e.g., Bräutigam 2019; Bräutigam and Kidane 2020; Jones and Hameiri 2020).

This debate in large part is based on conjecture. Neither policymakers nor scholars know if Chinese loan contracts would help or hobble borrowers, because few independent observers have seen them. Existing research and policy debate rests upon anecdotal accounts in media reports, cherry-picked cases, and isolated excerpts from a small number of contracts. Our paper seeks to address this gap in the literature.

We present the first systematic analysis of China's foreign lending terms by examining 100 debt contracts between Chinese state-owned entities and government borrowers in 24 countries around the world, with commitment amounts totaling $36.6 billion. All of these contracts were signed between 2000 and 2020. In 84 cases, the lender is the Export-Import Bank of China (China Eximbank) or China Development Bank (CDB). Many of the contracts contain or refer to borrowers’ promises not to disclose their terms—or, in some cases, even the fact of the contract's existence. We were able to obtain these documents thanks to a multi-year data collection initiative undertaken by AidData, a research lab at William and Mary. AidData's team of faculty, staff, and research assistants identified and collected electronic copies of 100 Chinese loan contracts (not summaries or excerpts of these contracts) by conducting a systematic review of public sources, including debt information management systems, official registers and gazettes, and parliamentary websites.[3] In partnership with AidData, we have digitized and published each of these contracts in a searchable online repository (see https://www.aiddata.org/how-china-lends). [4]

Our sample of 100 contracts with Chinese creditors represents a small part of the more than 2000 loan agreements that China's state-owned lenders have signed with developing countries since the early 2000s (Horn et al. 2019). However, it is sufficiently large to make clear that Chinese entities use standardized contracts, and to identify a handful of prevalent contract forms, which appear to vary by lender. Each Chinese entity in our sample uses its own contract form across all of its foreign borrowers. Three main forms, or contract types, occur most often in our sample: the CDB loan contract, the China Eximbank concessional loan contract, and the China Eximbank non-concessional loan contract (see Appendix II for our typology). We find substantial overlap in how these entities write debt contracts with foreign governments, which suggests that our sample is informative of the larger universe of other CDB and China Eximbank contracts.

We have analyzed the full text of every contract document we could find. We are not aware of any analysis of sovereign debt contracts with Chinese lenders that uses more than a handful of contracts or contract excerpts. Having access to the entire universe of sovereign debt contracts, including but not limited to those with Chinese lenders, would be preferable—but most of these contracts are shrouded in secrecy. Until disclosure becomes the norm, being able to evaluate and compare 100 contract texts is a significant step forward.

We start by coding the terms and conditions of the 100 Chinese debt contracts we found. In addition to the key financial characteristics of each contract (principal, interest, currency, maturity, amortization schedule, collateral, and guarantees), we code key non-financial terms that have played important roles in contemporary sovereign debt contract practice. These include priority (status), events of default and their consequences (including cross-default and acceleration), termination and cancellation, enforcement (including waiver of immunity and governing law), and confidentiality.

We then endeavor to evaluate China's contracts in a broader international sovereign debt contracting context. For this purpose, alongside the contracts with Chinese lenders, we code a benchmark set of foreign debt contracts that consists of 142 loans from 28 commercial, bilateral, and multilateral creditors. With few exceptions, neither sovereign debtors nor their creditors normally publish their contract texts in full. Our benchmark contracts are from Cameroon, the only developing country that, at the time of our study, had published all of its project-related loan contracts with foreign creditors of all types, entered into between 1999 and 2017. We compare the Chinese contract terms with those in the benchmark sample, as well as the model commercial loan contract published by the London-based Loan Market Association (hereinafter “the LMA template”).

The summary results of our analysis are as follows. First, China's state-owned entities blend standard commercial and official lending terms, and introduce novel ones, to maximize commercial leverage over the sovereign borrower and to secure repayment priority over other creditors. The following examples illustrate:

-

All of the post-2014 contracts with Chinese state-owned entities in our sample contain or reference far-reaching confidentiality clauses. [5] Most of these commit the debtor not to disclose any of the contract terms or related information unless required by law. [6] Only 2 of the 142 contracts in the benchmark sample contain potentially comparable confidentiality clauses. Commercial debt contracts, including the LMA template, impose confidentiality obligations primarily on the lenders. Borrower confidentiality obligations outside the Chinese sample are rare and narrowly drawn. Broad borrower confidentiality undertakings make it hard for all stakeholders, including other creditors, to ascertain the true financial position of the sovereign borrower, to detect preferential payments, and to design crisis response policies. Most importantly, citizens in lending and borrowing countries alike cannot hold their governments accountable for secret debts.

-

30 percent of Chinese contracts in our sample (representing 55 percent of loan commitment amounts) require the sovereign borrower to maintain a special bank account—usually with a bank “acceptable to the lender”—that effectively serves as security for debt repayment. Banks typically have the legal and practical ability to offset account holders’ debts against account balances. These set-off rights can function as cash collateral without the transparency of a formal pledge. Contracts in our sample require borrowers to fund special accounts with revenues from projects financed by the Chinese lender, or with cash flows that are entirely unrelated to such projects. In practice, this means that government revenues remain outside the borrowing country and beyond the sovereign borrower's control. Offshore accounts are common in limited-recourse project finance transactions, but they are highly unusual in contemporary, full-recourse sovereign lending. [7] In our benchmark sample, we find only three analogous arrangements: one each with a multilateral, a bilateral, and a commercial lender. The U.S. emergency loan to Mexico in 1995, which required oil revenues to flow through an account at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, is a high-profile exception that proves the rule. One needs to go back to the 19th and early 20th century to find similar security arrangements in sovereign lending on the scale that we observe in our Chinese contract sample (Borchard and Hotchkiss 1951; Wynne 1951; Maurer 2013). When combined with confidentiality clauses, revenue accounts pose significant challenges for policymaking and multilateral surveillance. If a substantial share of a country's revenues is under the effective control of a single creditor, conventional measures of debt sustainability are likely to overestimate the country's true debt servicing capacity and underestimate its risk of debt distress.

-

Close to three-quarters of the debt contracts in the Chinese sample contain what we term “No Paris Club” clauses, which expressly commit the borrower to exclude the debt from restructuring in the Paris Club of official bilateral creditors, and from any comparable debt treatment. These provisions predate and stand in tension with commitments China's government has made under the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI (the “Common Framework”), announced in November 2020. The framework commits G20 governments to coordinate their debt relief terms for eligible countries.

-

All contracts with China Eximbank and CDB include versions of the cross-default clause, standard in commercial debt, which entitles the lender to terminate and demand immediate full repayment (acceleration) when the borrower defaults on its other lenders. Some contracts in our sample, discussed in more detail below, also cross-default to any action adverse to China's investment interests in the borrowing country. Every commercial contract in our benchmark sample includes a cross-default clause, as does the LMA template. Only around half of all bilateral official debt contracts, and just 10 percent of multilateral debt contracts in the benchmark sample contain cross-default clauses. Instead, multilateral debt contracts usually let the lender suspend or cancel the contract if the debtor fails to perform its obligations under different contracts with the same lender, or in connection with the same project. Both cross-default and cross-suspension clauses put pressure on the debtor to perform or renegotiate, but they serve somewhat different purposes. A commercial cross-default clause helps protect creditors from falling behind in the payment queue; a cross-suspension clause lets a policy lender pause disbursements when the debtor's policy or project effort—or its relationship with the lending institution—deteriorates. Some Chinese contracts combine elements of both, further constraining the sovereign borrower.

Second, several contracts with Chinese lenders contain novel terms, and many adapt standard commercial terms in ways that can go beyond maximizing commercial advantage. Such terms can amplify the lender's influence over the debtor’s economic and foreign policies. For instance,

-

50 percent of CDB contracts in our sample include cross-default clauses that can be triggered by actions ranging from expropriation to actions broadly defined by the sovereign debtor as adverse to the interests of “a PRC entity.” These terms seem designed to protect a wide swath of Chinese direct investment and other dealings inside the borrowing country, with no apparent connection to the underlying CDB credits. They are especially counterintuitive in light of China's characterization of CDB as a “commercial” lender. No contract in our benchmark sample contains similar terms.

-

All CDB contracts in our sample include the termination of diplomatic relations between China and the borrowing country among the events of default, which entitle the lender to demand immediate repayment.

-

More than 90 percent of the Chinese contracts we examined, including all CDB contracts, have clauses that allow the creditor to terminate the contract and demand immediate repayment in case of significant law or policy changes in the debtor or creditor country. 30 percent of Chinese contracts also contain stabilization clauses, common to non-recourse project finance, whereby the sovereign debtor assumes all the costs of change in its environmental and labor policies. Change-of-policy clauses are standard in commercial contracts, including the LMA template, but they take on a different meaning when the lender is a state entity that may have a voice in the policy change, rather than a private firm on the receiving end of new financial regulations or UN sanctions. At the extreme, policy change clauses could allow the state lender to accelerate loan repayment and set off a cascade of defaults in response to political disagreements with the borrowing government.

Overall, the contracts in our sample suggest that China is a muscular and commercially-savvy lender to developing countries. Chinese contracts contain more elaborate repayment safeguards than their peers in the official credit market, alongside elements that give Chinese lenders an advantage over other creditors. At the same time, many of the terms and conditions we have reviewed exhibit a difference in degree, not in kind, from commercial and other official bilateral lenders. All creditors, including commercial banks, hedge funds, suppliers, and export credit agencies, seek a measure of influence over debtors to maximize their prospects of repayment by any legal, economic, and political means available to them (e.g., Gelpern 2004; Gelpern 2007; Schumacher et al. 2021). However, China's contracts also contain unique provisions, such as broad borrower confidentiality undertakings, the promise to exclude Chinese lenders from Paris Club and other collective restructuring initiatives, and expansive cross-defaults designed to bolster China's position in the borrowing country. Our analysis also calls attention to terms that might be unremarkable in a commercial debt contract, such as the policy change event of default, which could acquire a different meaning and new potency in government-to-government lending arrangements.

It bears emphasis that our study does not systematically address contract implementation and enforcement, for which there is limited anecdotal evidence. It is entirely possible that some of the contract features we identify serve an expressive purpose, or function in terrorem, to dissuade the debtor from taking steps adverse to the creditor's interests. Several of the unusual terms we identify, including the promise to forswear restructuring, would likely be unenforceable in court in a major financial jurisdiction. Because most of the contracts in our sample specify Chinese governing law and arbitration in China, we cannot predict how the terms in question would fare in a dispute. Any given lender might prefer to avoid adjudication or arbitration altogether. Nonetheless, promises that eventually turn out to be unenforceable could be a source of formal and informal pressure on the debtor, especially if the creditor invokes their breach to block a special revenue account it controls.

The enforcement terms themselves—choice of law, forum selection, and waivers of sovereign immunity—have attracted attention in policy and research circles (e.g., Bräutigam et al. 2020), but look mostly unremarkable to us. Like other bilateral creditors in the benchmark sample, China Eximbank insists on its domestic governing law and a dispute resolution forum in its home country. While China Eximbank contracts usually specify arbitration before the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC) and using its procedures, both commercial and bilateral official creditors that agree to submit their disputes to arbitration choose the procedural rules of the London-based International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). CDB follows commercial practice in this area: seven out of eight CDB contracts in our sample are governed by English Law; one is governed by New York Law; they specify different arbitration venues and ICC rules. Sovereign immunity waivers in the Chinese sample contracts are generally in line with the LMA template and the commercial contracts in our benchmark set. In sum, despite their media prominence, the enforcement terms in China's contracts appear to be broadly consistent with the practices of other lenders. We are not in a position to evaluate the substance of Chinese law or China's commercial dispute resolution regime in this study; nor do we opine on the merits of customary international practice. We simply note that the choice of creditors’ domestic law to govern a debt contract appears to come with the territory.

Our findings, while based on a limited sample of contracts, have significant implications for sovereign debt contracting, sovereign debt policy, and the academic literature on sovereign debt.

Lending to sovereign governments occurs in an environment of limited and indirect enforcement, with incomplete and uneven contract standardization and no statutory or treaty bankruptcy to supply generally accepted default outcomes. As a result, even when we find troubling terms in debt contracts between sovereign borrowers and China's state-owned entities, we cannot conclude that they violate international standards: with few exceptions, such standards do not exist. On the other hand, we suspect that the contracts we have examined are both more common than had been understood and a sign of things to come. New and hybrid lenders that mix official and commercial institutional features are growing in importance for sovereign financing. These are not limited to China. We expect such lenders to adapt and innovate contract features to maximize their commercial and political advantage in an increasingly crowded field.

In the immediate future, our analysis should help inform the ongoing discussions on how to address the risk of debt distress across developing countries (e.g., IMF and World Bank 2020), including via global initiatives such as the Common Framework (Group of 20 2020). China's distinct approach to lending and debt restructuring has already created tensions between China and traditional multilateral lenders, between China and the rest of the G20, and between China and private creditors in countries like Zambia. [8]

Our main contribution to the academic literature on sovereign debt is to show how China has adapted sovereign debt contracts to manage repayment risk under conditions of weak contract enforcement (Tirole 2003; Aguiar and Amador 2015). A longstanding puzzle in international macroeconomics is why private investment and lending to developing countries is so limited (Lucas 1990). One explanation is that investments in high-risk countries simply do not pay off in light of their weak institutions and the associated expropriation risk (Alfaro et al. 2008), as well as the high likelihood of sovereign defaults (Reinhart et al. 2003).

We show how Chinese state-owned banks use contract tools to manage these and other risks. They adapt legal and financial engineering tools—some new and others over a century old—to protect their investments and climb the “seniority ladder,” potentially gaining repayment advantage over other creditors. We thereby add to the literature on seniority in sovereign debt markets, which has yet to examine the role of China and other new creditors (e.g., Bolton and Jeanne 2009; Chatterjee and Eyigungor 2015; Schlegl, Trebesch, Wright 2019). We also contribute to a large body of research studying international agreements that are hard to enforce, such as trade agreements (e.g. Horn, Maggi, and Staiger 2010; Maggi and Staiger 2011). Lastly, our paper is unique for its focus on a hybrid contract form—debt contracts between governments and state-owned entities that meld commercial and official contracting practices and innovate on both. These types of hybrid contracts between sovereign or quasi-sovereign entities of different countries have received little attention in the literature, but merit study as a distinct and growing phenomenon.

The paper begins by introducing a new dataset of 100 sovereign debt contracts with Chinese state-owned lenders and a benchmark sample of 142 sovereign debt contracts between Cameroon and a broad range of bilateral, multilateral, and commercial creditors. We then describe the methods we use to evaluate the terms and conditions in these contracts and present the main insights by focusing on specific provisions that set Chinese lenders apart from their peers and competitors from other countries. We conclude with a discussion of policy considerations.

Section 2 Dataset and methodology: Coding the terms of 100 Chinese and 142 benchmark debt contracts

This section introduces our new dataset of sovereign debt contracts. Section 2.1 focuses on the 100 Chinese debt contracts, presents summary statistics, and discusses the extent to which the sample is representative of the population of China's official foreign lending activities. Section 2.2 presents key characteristics of the benchmark sample and discusses its similarities and differences with the Chinese contract sample. In Section 2.3 we outline the methodology that we developed to code the terms of Chinese and benchmark contracts.

2.1 The Chinese contract sample

Despite its size and rapid growth, China's foreign lending remains opaque. The Chinese government has resisted pressure to reveal the size, scope, and terms of its claims on low- and middle-income countries (Dreher et al. forthcoming). This secrecy has been a focus of public debate for a long time. For example, in 2011, a group of bilateral and multilateral creditors urged China to comply voluntarily with information disclosure standards of the OECD's Development Assistance Committee (DAC). The Chinese authorities rejected the call, arguing that the “principle of transparency should apply to north-south cooperation, but [...] it should not be seen as a standard for south-south cooperation.” [9] Ten years later, China still does not participate in the OECD's Creditor Reporting System, the OECD Export Credit Group, or the Paris Club—although its recent commitment to the G20 Common Framework may indicate an evolving position.

To address the evidence gap, we collaborated with AidData—a research lab at the College of William and Mary—to identify all publicly accessible loan agreements between Chinese government institutions and state-owned banks, and sovereign borrowers from low- and middle-income countries. [10] In preparation for the 2021 update of its Global Chinese Official Finance Dataset, AidData recently revised its Tracking Underreported Financial Flows (TUFF) methodology. It now requires the systematic implementation of search procedures that enable the identification of loan agreements in the debt information management systems, official registers and gazettes, and parliamentary websites of low- and middle-income countries.

The implementation of these search procedures resulted in the retrieval of 100 loan agreements between Chinese government institutions and state-owned banks, and government entities in 24 borrowing countries, with a total commitment value of $36.6 billion. All of these loan agreements were drawn from publicly available sources. The dataset consists of every contract that AidData retrieved during the implementation of its updated TUFF methodology; no contract was excluded. The dataset represents about 5% of total estimated Chinese lending between 2000 and 2017 (Horn et al. 2019 estimate total direct lending commitments of $560 billion). As shown in Table 1, our sample includes concessional and non-concessional debt contracts entered into between 2000 and 2020 with China's two main policy banks (China Eximbank and CDB), state-owned commercial banks (Bank of China, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China), state-owned enterprises (e.g., Sinohydro, China Machinery Engineering Corporation) and the central government.

|

Creditor agency |

Number of contracts |

Commitment amounts (in bn USD) |

Loan Type |

|

Export-Import Bank of China |

76 |

15.9 |

|

|

Government Concessional Loan |

36 |

2.9 |

Concessional |

|

Preferential Buyer Credit Loan |

30 |

9.1 |

Concessional |

|

Buyer Credit Loan |

5 |

3.1 |

Non-concessional |

|

Other |

5 |

0.8 |

|

|

China Development Bank |

8 |

16.1 |

|

|

China Development Bank only |

6 |

9.3 |

Non-concessional |

|

Co-financed |

2 |

6.8 |

Non-concessional |

|

State-owned commercial banks |

8 |

1.7 |

|

|

Industrial and Commercial Bank of China |

3 |

0.8 |

Non-concessional |

|

Bank of China |

1 |

0.3 |

Non-concessional |

|

Other |

4 |

0.7 |

Non-concessional |

|

Supplier credits |

4 |

2.8 |

|

|

Consortium |

1 |

0.4 |

Non-concessional |

|

China Machinery Engineering Corporation |

1 |

0.6 |

Non-concessional |

|

Poly Changda |

1 |

0.1 |

Non-concessional |

|

Sinohydro |

1 |

1.7 |

Non-concessional |

|

Chinese government |

4 |

0.1 |

Concessional |

Note: This table shows the composition of our Chinese contract sample by creditor agency. Commitment amounts are provided in billions of current USD. Classification into concessional and non-concessional credits is based on financial terms. Non-concessional credits are usually extended at a spread of 2 or 3 percentage points over a market-based reference interest rate such as LIBOR, whereas concessional loans tend to be extended at fixed interest rates of 2 or 3 percent, effectively incorporating a grant element (also see Appendix II).

China Eximbank accounts for 76 of the 100 loan agreements in the sample. Out of these 76 loans, 66 are concessional lending instruments (so called Government Concessional Loans or Preferential Buyer Credits). [11] The sample only includes 8 loan contracts with CDB, two of which were co-financed with Chinese state-owned commercial banks. [12] However, the small number of CDB loan agreements in our sample corresponds to substantially larger financial commitment amounts: 8 contracts represent 44% of the overall lending volume captured in our sample. [13] Compared to China Eximbank and CDB lending, loans issued by China's state-owned commercial banks, state-owned enterprises, and the central government are small. Taken together, these three groups of lenders account for only 16 percent of the contracts and 13 percent of the lending volume in our sample.

The distribution of creditors within our sample is broadly in line with creditor composition in the datasets of Morris et al. (2020) and of Horn et al. (2019). In both of these datasets, China Eximbank and CDB represent by far the two most important sources of China's international financial commitments. Morris et al. (2020: 46) analyze 1,046 Chinese government loans to 130 countries between 2000 and 2014 and find that 80 percent of the loans during this period came from China Eximbank and 14 percent came from CDB. While China Eximbank makes a far larger number of loans than CDB, the average size of its loans is substantially smaller than those made by CDB. As a result, in the Morris et al. (2020) dataset, loan commitments from China Eximbank account for 55 percent of overall lending and loan commitments from CDB lending account for 36 percent of overall lending. Very similar patterns are observed in the dataset constructed by Horn et al. (2019). In their dataset, loans from China Eximbank account for 60 percent of the total by number, and 33 percent of the total by monetary value, while loans from CDB represent 18 percent of the total by number, and 42 percent of the total by monetary value.

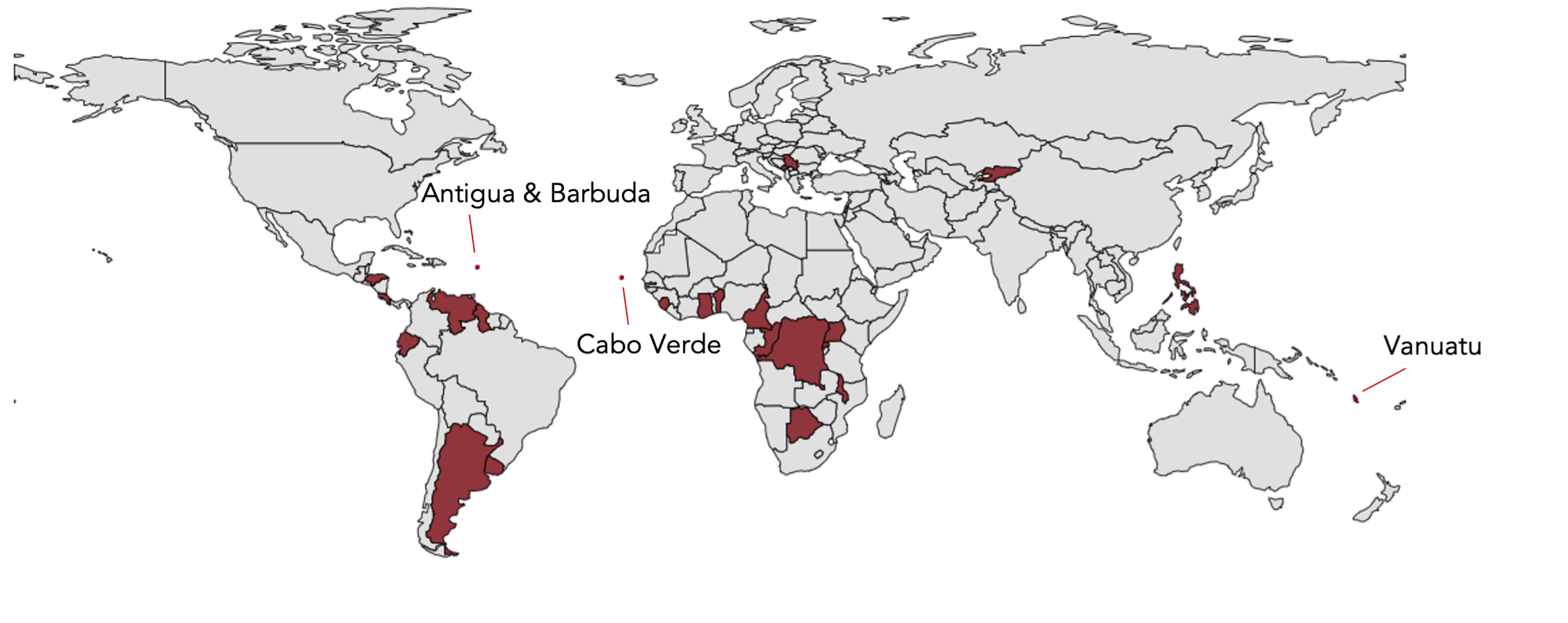

Figures 1 and 2 further demonstrate that our sample is broadly dispersed across world regions (also see Table A1 in Appendix I for a detailed country list). 47 percent of the loan agreements in the sample are with government borrowers in Africa, and another 27 percent are with government borrowers in Latin America and the Caribbean. The remaining loans in the sample were made to government borrowers in Eastern Europe (11%), Asia (10%), and Oceania (5%).

Previous studies demonstrate that Africa, Asia and Latin America are the primary destinations for Chinese government loans (Horn et al. 2019; Dreher et al. 2021). Therefore, our sample likely under-represents Chinese lending to Asia. If Chinese contracts varied systematically by region, this would be of concern for the external validity of our sample. We do not find evidence, however, that contracts differ significantly by geographic region. In fact, our analysis of Chinese contracts reveals that the lending terms are highly standardized, and largely predetermined by the identity of the creditor and the type of lending instrument.

The distribution of our sample is broadly consistent with the global distribution of Chinese government loans by borrowing country income level. Borrowers in middle-income countries account for 90 percent of the loan agreements in the sample, while borrowers in low-income (8%) and high-income countries (2%) account for the remainder. By comparison, the analysis of Horn et al. (2019) demonstrates that, since the turn of the century, Chinese state-owned creditors have made approximately 75 percent of their loans to middle-income countries, 19 percent to low-income countries, and 6 percent to high-income countries.

We conclude from these summary statistics that our sample of 100 contracts is generally in line with the composition of China's global portfolio of loans to government borrowers. While certain subgroups may be over- or under-represented in the data, there is no indication of systematic bias in the composition of the sample. More importantly, our analysis of contracts shows that Chinese lending instruments are highly standardized and do not exhibit significant variation by borrower country, region, or income bracket. Nonetheless, it bears emphasis that this dataset of Chinese debt contracts does not constitute a random sample; the contracts included in our analysis were selected because they were the only ones publicly available at the time of this study.

2.2 The benchmark debt contract sample

China is a state-led economy, and its approach to government-to-government lending often differs from those of OECD governments. We observe a greater array of lenders, terms, and policy mandates in Chinese debt contracts than we do with other governments. To account for the fact that China does not have an obvious peer group within the sovereign lending ecosystem, we established four separate peer groups for benchmarking purposes: (1) bilateral creditors from the OECD, which include government agencies and instrumentalities that coordinate through the OECD's Development Assistance Committee (DAC); (2) non-OECD bilateral creditors (i.e., government creditors from countries that do not participate in DAC, such as the Gulf states or India); (3) multilateral creditors, including regional development banks; and (4) commercial banks. We refer to creditors in the first three categories collectively as official creditors.

China is not unique for failing to publish detailed information about its lending terms. There is no uniform public disclosure standard or practice for bilateral official lenders, although many governments and most multilateral institutions publish information about their lending at varying levels of detail, and many share such information with a subset of other creditors. To address this information gap, particularly when it comes to comparability at the contract level, we constructed a benchmark sample for a single sovereign borrower, Cameroon, which to our knowledge is the only developing country that has maintained a publicly accessible database (via http://dad.minepat.gov.cm/) of its project-related loan contracts with all external creditors. [14]

This database, in principle, should cover all of the Government of Cameroon's project-related loan contracts with external creditors. However, some of the contracts that are stored in the database are incomplete or in an unreadable condition. Also, for some of the loans in the database, no contractual documentation was available. [15] In total, we were able to retrieve 142 debt contracts with 28 different creditors—8 commercial banks, 10 bilateral creditor agencies from 10 different countries (including 3 official export credit agencies), and 11 inter-governmental organizations—that are listed in detail in Table A2 in Appendix I. The composition of the sample is summarized in Figure 4. The International Development Association (IDA), the Islamic Development Bank (ISDB), the African Development Bank (AfDB) and Agence Française de Développement (AFD) are heavily represented in the benchmark set, which likely reflects their institutional mandates and Cameroon's colonial history.

In order to gauge whether the loans in the benchmark sample and the China sample are reasonably comparable, we explore whether they were designed to achieve similar purposes. Figure 5 summarizes the sectoral composition of loans in the China and the benchmark sample. We find considerable overlap between the samples: in both the benchmark and the China sample, most loans financed projects and programs in the transportation, energy, and water supply sectors. These three areas account for roughly 60 percent of the contracts in the Chinese sample and for 50 percent of the contracts in the benchmark sample.

The types of borrowers represented in the benchmark sample and the China sample are also remarkably similar. In both samples, the borrower is almost always the central government (99% in the benchmark sample and 94% in the China sample). The remaining borrowers are state-owned enterprises, a government agency, and two special purpose vehicles (project companies) with explicit guarantees from the central government (see Figure 6 below).

In our main analysis, we compare the lending terms of the 100 Chinese contract sample with the 142 contracts of the 28 benchmark creditors. Our analysis therefore entails comparisons of Chinese contracts with borrowers worldwide (including Cameroon) to benchmark contracts with Cameroon as a single sovereign debtor country. This comparison introduces scope for bias if Chinese lending contracts with sovereign borrowers outside Cameroon differ substantially from Chinese loan contracts with Cameroon. Fortunately, this does not appear to be the case, since the terms of Chinese lending contracts in our sample are highly standardized across countries. As we show in Appendix III, all of our main findings hold when we limit our comparison to Chinese and benchmark creditor contracts with Cameroon.

A related concern is that specific characteristics of Cameroon as a borrower could make contracting practices there difficult to compare to contracting practices elsewhere. In other words, our benchmark sample could differ for other developing and emerging market countries. All the evidence we have seen reinforces our impression of standardization by creditor, with banks typically following the LMA template, and bilateral and multilateral creditors relying heavily on their respective general terms and conditions. In order to reflect the high degree of standardization, we have created a typology of contract characteristics by creditor in Appendix II. Nonetheless, we cannot rule out that Cameroon's contracts differ systematically in some way, given the dearth of systematic data and the lack of publicly available sovereign loan contracts. With more data, we could expand our analysis to a broader range of benchmark countries and their contracts with bilateral, multilateral and private creditors.

2.3 Methodology and coding approach

In order to facilitate comparisons between the terms and conditions in the sample of Chinese loan contracts and the benchmark loan contracts, we developed a set of variables that allow for systematic categorization. The variables that we selected follow the structure of the Loan Market Association (LMA) template for single currency term facility agreements in developing markets. We took this approach because, while there is no “international standard” for bilateral official sovereign debt contracts, a variety of private and some official lenders—inside and outside of China—use the LMA template as a basis for their contract design. In total, we code 100 variables, which we group into eight analytical categories:

-

Principal Payment Terms: These variables capture the loan facility, its debt maturity, grace period, repayment schedule, and currency of denomination, as well as bilateral cancellation and debtor prepayment rights.

-

Interest and Fees: The variables in this category identify the interest rate, timing and currency of interest payment, as well as the commitment fee and the arrangement or management fee.

-

Additional Payment Obligations: This is a catch-all qualitative variable created to capture any payment obligations of the borrower not included in (1) and (2), such as currency conversion costs, indemnification costs, or charges related to contract renegotiation or enforcement. This category also captures stabilization or increased cost clauses that require the borrower to compensate the lender for increased costs resulting from policy changes in the borrower country or the creditor country.

-

Credit Enhancement: These variables capture information about third-party credit enhancements and security interests. They cover guarantees (including guarantor identity and guarantee terms and conditions), formal and informal security interests, and escrow and special accounts [16] (including account funding and management arrangements).

-

Conditions, Covenants, and Modification Terms: These variables identify the debtor's commitments apart from the promise to repay the debt with interest. They include commitments addressing status (subordination and pari passu clauses, if any), information disclosure, negative pledge, collective and bilateral restructuring procedures, if any, and linkages to any other contracts, including commodity sales and project operation.

-

Events of Default: These variables identify events of default and their consequences, including acceleration of repayment, suspension of disbursement, and contract termination. Varieties of the cross-default clause feature prominently in the sample and the benchmark contract set.

-

Assignment and Delegation: These variables capture whether and under what conditions the sovereign debtor or the creditor may assign its rights or delegate its obligations to a non-party.

-

Governing Law and Enforcement: These variables identify the law that governs the contract and the agreed dispute settlement forum and procedure (including arbitration and any applicable procedural rules). They cover sovereign immunity waivers, if any, and separately describe waivers of the debtor's immunity from lawsuits and of the immunity of its assets from attachment before and after a court judgment, where applicable.

Dealing with missing information: Some loan contracts in our data are incomplete or reference additional agreements that are not available to us. In particular, 18 percent of contracts in our sample are missing one or more pages. In these cases, the table of contents can usually be used to infer which parts of the contract are missing. [17] If a contract is incomplete, we cannot rule out that a certain clause exists in the contract. We therefore assign “missing values” rather than “zeros” in such cases. We do so to ensure that contracts with missing information do not enter the sample statistics for the incidence of a specific clause.

Another related problem emerges if a contract references additional legal documents that are not available to us. By way of example, a creditor's “general conditions” can form an integral part of the contract, but they were not consistently available to us. While none of the Chinese contracts refer to separate general conditions, most multilateral and some bilateral creditors use them. In 42 cases (17% of contracts), general conditions are not available to us. In the Chinese contract sample, seven contracts represent only technical and economic cooperation agreements that leave most contractual details to the final (undisclosed) loan agreement. All of these transactions are flagged in our dataset. When coding the information from these contracts, we again assign “missing values” if we cannot find a clause in the contract, since we cannot rule out that the clause is included in the creditor's general conditions or in the final version of the loan agreement.

Similarly, contracts in our samples often reference separate confidentiality agreements, account agreements, or security documents that form part of the transaction and define important terms. In these cases, we know that a certain clause or arrangement exists, but have only limited insights into the details. We discuss these limitations of our study in the presentation of our findings below.

Coding approach: We employed two independent research teams—one at the Georgetown University Law Center and another at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy—to apply a consistent set of variable definitions and coding rules and procedures to the 100 contracts in the Chinese sample and the 142 contracts in the benchmark set. When the coding determinations of these teams were identical, we accepted their assigned values as final. When the two teams reached different coding determinations, we enlisted the support of a senior researcher to identify the underlying source of the discrepancy and apply expert judgment to assign a final value.

We provide more information on the definitions of our variables and the coding rules and procedures that we used to construct the variables in Appendix VI. Our dataset can be accessed at https://www.aiddata.org/how-china-lends. Digitized and scanned PDF copies of the loan agreements that we coded can also be accessed at https://www.aiddata.org/how-china-lends.

Section 3 Main findings

We compared the terms and conditions of contracts between Chinese lenders and developing country borrowers with those in the benchmark set of Cameroon's project-related debt contracts with external creditors. Tables A4 to A8 in Appendix II provide a broad overview and Appendix III provides robustness checks by comparing Chinese and non-Chinese contracts within the Cameroon sample. These comparisons reveal that debt contracts with Chinese state-owned entities differ substantially from those in the benchmark sample across three key dimensions: (1) confidentiality, (2) seniority, and (3) lender discretion, particularly with respect to contract termination and certain events of default. Below we review key differences between the terms in the Chinese contract sample and their counterparts in the benchmark sample. We also identify those terms that appear to be unique to Chinese lenders, with no ready parallels in the benchmark sample.

3.1 Confidentiality: Chinese contracts contain unusual confidentiality clauses

Sovereign debt contracts with Chinese lenders are more likely to include confidentiality clauses than similar contracts with most other creditors. All CDB contracts and 43% of China Eximbank contracts include such clauses. Some form of confidentiality clause is also common in the benchmark sample: 39 percent of contracts by multilateral creditors, one third of contracts by bilateral creditors and one third of commercial bank contracts include confidentiality undertakings. While benchmark contracts impose confidentiality obligations primarily on the lenders, contracts in our Chinese sample impose them on the borrowers. Confidentiality clauses in Chinese lenders’ contracts are also far broader in scope than those in the benchmark set, covering all the terms, and even the existence of the debt itself.

Figure 7 shows a pronounced shift towards greater secrecy in Chinese lending contracts that is driven by the widespread introduction of confidentiality clauses in China Eximbank contracts around 2014. Whereas only one of 37 China Eximbank contracts prior to 2014 contains a confidentiality clause, all China Eximbank contracts after 2014 include confidentiality clauses.

All China Eximbank contracts beginning in 2014 use substantially the same confidentiality clause, reproduced in Table 2 below. The CDB contracts in our sample follow the LMA template, and also reference separate confidentiality letters. The only publicly available letter of this kind is designed to protect the confidentiality of contract negotiations: it covers all aspects of the transaction and related negotiations, applies to both parties, and expires six months after the contract is signed, or one year after negotiations break up. [18] In our benchmark sample, one-third of the commercial loan contracts use formulations that are nearly identical to or slightly narrower than the confidentiality clause in the LMA template reproduced in Table 2 below.

|

China Eximbank (all contracts after 2014) |

LMA Template (33% of the banks in our sample) |

Islamic Development Bank (all 20 contracts) |

Agence Française de Développement (AFD) (2 out of 10 contracts) |

|

The Borrower shall keep all the terms, conditions and the standard of fees hereunder or in connection with this Agreement strictly confidential. Without the prior written consent of the Lender, the Borrower shall not disclose any information hereunder or in connection with this Agreement to any third party unless required by applicable law. |

Each Finance Party [defined as lenders] agrees to keep all Confidential Information [enumerated items] confidential and not to disclose it to anyone, save to the extent permitted by Clause 36.2 (Disclosure of Confidential Information) [and Clause 36.3 (Disclosure to numbering service providers)], and to ensure that all Confidential Information is protected with security measures and a degree of care that would apply to its own confidential information. The Agent and each Obligor agree to keep each Funding Rate ... confidential and not to disclose it to anyone, save to the extent permitted by paragraphs ... below. ... The Agent and each Obligor acknowledge that each Funding Rate ... is or may be price-sensitive information and that its use may be regulated or prohibited by applicable legislation including securities law relating to insider dealing and market abuse and the Agent and each Obligor undertake not to use any Funding Rate ... for any unlawful purpose. |

All of the bank's documents, as well as its correspondence and records, need to be kept confidential by the borrower. |

The Borrower shall not disclose the contents of the agreement without the prior consent of the Lender to any third party, unless required by law, applicable regulation or a court decision. |

The China Eximbank confidentiality clause excerpted here binds the sovereign debtor. It applies to the entire agreement and, potentially, to a broader set of dealings between the debtor and China Eximbank “in connection with” the contract. On the other hand, the clause contains a carve-out that would allow the sovereign debtor to make disclosure required by law. It is unlikely, however, that this carve-out would be broad enough to allow a debtor to disclose China Eximbank contract terms to its Paris Club creditors, since the Paris Club process and output are at best “soft law.” The LMA template, in contrast, imposes more robust non-disclosure obligations on the lenders (“finance parties”), which presumably reflects the fact that banks obtain confidential business information in the course of their credit assessment before they issue a loan. The debtor nondisclosure obligations are narrowly drawn, limited to banks’ funding costs, and expressly justified by reference to securities regulations. [19]

The Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa, the Islamic Development Bank, the OPEC Fund for International Development and the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development all have a version of the clause, reproduced in Table 2, that requires the borrower to keep the lender's documents and correspondence confidential. It is much narrower than the China Eximbank clause. Two official bilateral debt contracts in our benchmark sample, both from Agence Française de Développement (AFD), have confidentiality terms resembling China Eximbank’s, committing the debtor not to disclose any of the agreement.

Expansive debtor confidentiality undertakings that extend beyond contract negotiation present multiple political and debt management problems. First, they try to hide government borrowing from the people whose taxes are bound to repay it. Second, they impede budget transparency and sound fiscal management. Third, they hide the sovereign's true financial condition from its other creditors. Creditors may charge the government higher interest rates to reflect the uncertainty and potential for subordination. Fourth, potential for hidden debt can impede debt restructuring. At this writing, Zambia's bondholders are refusing to proceed with debt renegotiation citing insufficient information about China's claims on the country (Bavier and Strohecker 2021). More broadly, a lack of trust in the debtor's financial reporting can derail crisis response and recovery.

We have not found any evidence of judicial enforcement of the confidentiality clauses, but we have identified at least one instance of CDB invoking them in response to a video obtained and released by investigative journalists that revealed the terms of Ecuador's multi-billion dollar oil-backed debt to CDB. The release of the video shortly after the deal was signed prompted public debate about the new borrowing (Zurita et al. 2020). In response, the head of CDB's Resident Mission in Ecuador wrote to his counterpart in Ecuador's Ministry of Finance, complaining about the borrower's apparent breach of the confidentiality letter, called on the Ecuadorian government to launch a leak investigation, and demanded that it take measures to mitigate the reputational damage to CDB caused by the video. [20] The CDB letter also implicitly threatened to withhold future financing if the borrower did not adequately address the incident.

3.2 Seniority and Security: Chinese lenders use formal and informal collateral arrangements to maximize their repayment prospects

Chinese state-owned banks use liens, escrow and special accounts much more extensively than either the official or the commercial lenders in the benchmark set. Whereas 29% of the debt contracts in the Chinese sample use one or more of these devices, only 7% of OECD bilateral creditors and 1% of the multilateral creditors in the benchmark set do so. No contract with non-OECD bilateral creditors in the benchmark set uses any of these security devices.

Figure 8 further shows that collateralization practices vary across Chinese lending institutions: 6 out of 8 CDB loans in our sample benefit from some form of security interest, but only 22% of the China Eximbank loans do. [21] The distinct mandates of these institutions may help explain the difference: CDB operates without formal subsidies from the central government, and probably has stronger incentives than China Eximbank to write contracts to minimize repayment risk. Because CDB makes larger loans than China Eximbank, it must manage additional credit and liquidity risks. In our sample, the average face value of a China Eximbank loan is $200 million, while the average CDB loan has a face value of $1.5 billion. Any and all of these features would lead CDB to use credit enhancements when lending to risky borrowers.

The most common way of securing repayment in the Chinese contract sample is the use of escrow or special accounts. Sovereign borrowers commit to maintain and fund bank accounts either at the lending institution or at a bank “acceptable to the lender” throughout the life of the loan, and to route through these accounts project revenues and/or cash flows that are unrelated to the project funded by the loan. Debt contracts describe the accounts as part of the debt repayment process; however, they function above all as a security device.

The debt contracts in our sample and benchmark set reference separate account agreements that appear to contain most of the detailed provisions governing the accounts. We have access to only one such agreement in our sample, and therefore cannot provide a systematic assessment of how these accounts work. However, many of the debt contracts contain enough detail to convey a general sense of account operation.

-

All account arrangements with available information require the debtor to maintain a minimum account balance; in most cases, the minimum is the annual principal, interest, and fees due under the debt contract.

-

In 70% of the Chinese transactions with a special account, all revenues from the associated projects must be deposited in the account.

-

In 38% of the Chinese account arrangements, the account is financed from unrelated sources, either instead of or in addition to project revenues. In our sample, these sources include the export revenues from oil (Ecuador and Venezuela), bauxite (Ghana), and revenue from financial assets (Costa Rica). Other contracts require the borrower to provide sufficient funding from sources that are not limited to project revenues, but they do not specify the source(s).

-

In 5 CDB contracts (with Argentina, Ecuador and Venezuela), the lender also has the ability to block the debtor from withdrawing the funds. These contracts expressly limit the debtor's withdrawal rights to those specified in the account agreement. We have only one such account agreement: between CDB and a state-owned development bank (BANDES) in Venezuela. Under this agreement, BANDES is not permitted to make any withdrawals from the Collection Account during the 35-day period prior to any repayment date or if withdrawals would violate the minimum debt service coverage ratio. CDB, on the other hand, is “entitled at any time and without notice to BANDES, to […] appropriate, set-off or debit all or parts of the balances in the Collection Account to pay and discharge all or part of BANDES’ liabilities to CDB.” [22] In the 4.7 billion USD loan to Argentina's Ministry of Finance by CDB, ICBC and BOC, all project revenue is collected in a Project Trust Account and withdrawals are limited to pay for fees, loan repayments, and specified project expenses, in the prescribed order of priority. [23]

Box 1 illustrates the use of special accounts in a 2010 loan from CDB to the government of Ecuador. The loan agreement is linked to an oil purchase agreement between PetroEcuador and PetroChina. Our sample includes two additional oil-backed CDB loans to Ecuador and a similarly structured lending arrangement between CDB and BANDES in Venezuela.

Box 1. How revenue accounts work: CDB's oil-backed 2010 loan to Ecuador

In 2010, China Development Bank (CDB) extended a 1 billion USD oil-backed loan to the Ecuadorian Ministry of Finance.[24] The use of the loan is divided into two tranches. The first 80% of the commitment is at the free disposal of the Ministry to finance projects of infrastructure, mining, telecommunications, social development and/or energy. The remaining 20% are committed for the purchase of goods and services from selected Chinese contractors (p. 4).

The loan is backed by a separate Oil Sales and Purchase Contract between PetroEcuador and PetroChina. This agreement requires PetroEcuador to sell, over the entire validity period of the Facility Agreement, at least 380,000 barrels of fuel oil per month and 15,000 barrels of crude oil per day to PetroChina.[25] The oil proceeds are paid by PetroChina into the Proceeds Account which is opened by PetroEcuador with CDB in China and which is governed by Chinese law. PetroEcuador is “not permitted to make any withdrawals from the Proceeds Account except to the extent permitted under the Account Management Agreement” (p. 6). PetroEcuador and the Ecuadorian Ministry of Finance acknowledge that CDB has the “statutory rights under Chinese law and regulation […] to deduct or debit all or part of the balances in the Proceeds Account to discharge all or part of the Republic of Ecuador's [...] liabilities due and owing to CDB” both under the 2010 oil-backed loan as well as under “any other agreement between CDB and the Republic of Ecuador” (p. 6). The figure below illustrates.

Only 3 of the 142 contracts in our benchmark set have comparable account arrangements.

-

Cameroon's contract with Commerzbank Paris requires the government to deposit payments from the UN into an escrow account and to maintain a minimum account balance equal to a year's principal and interest payments due.

-

A contract between Cameroon and the French government development agency (AFD) requires the borrower to deposit royalty payments equal to 150% of annual payments due from Cameroon in an account formally pledged to AFD, and to maintain a minimum account balance equal to two loan payments due.

-

Provisions relating to a reserve account in a 2003 African Development Bank loan with Cameroon are illegible in the version of the contract that was published by the government of Cameroon.

Special accounts of the sort described here are standard in limited-recourse project finance.[26] Their function is to help lenders manage credit, operational, transfer, and legal risk, among others. Such accounts appear to be rare in bilateral official and multilateral lending practice. A handful of high-profile exceptions prove the rule:

-

U.S. emergency loans to Mexico beginning in 1982, and again in 1994, required Mexico to route proceeds from state oil sales through Mexico's account at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York; however, even under the more restrictive 1994 agreement, Mexico could withdraw the funds so long as it was not in default (General Accounting Office 1996). In addition, the United States committed to buy oil from Mexico at a discount price. The 1994 arrangement addressed a mix of financial and political imperatives, notably U.S. congressional opposition to the extraordinary assistance package.

-

Budget transparency, fiscal management, and related governance concerns led to the establishment of a London-based escrow account, which featured prominently in the World Bank's ill-fated financing for the Chad-Cameroon pipeline. Chad's petroleum revenues from the new pipeline flowed through the accounts between 2004 and 2006. Withdrawals had to be approved by a public oversight board before funds could be transferred to Chad's treasury. The World Bank suspended most disbursements to Chad and froze the account in 2006, after Chad changed its law and, according to the Bank, took fiscal measures in contravention of its agreement. Settlement later the same year allowed Chad to make a partial withdrawal; a subsequent review concluded that the arrangement was fragile and ultimately ineffective as a policy tool (World Bank 2006, 2009).

-

Offshore accounts and revenue pledges were popular in 19th and early 20th century sovereign lending, before the advent of restrictive sovereign immunity. Such arrangements had mixed success in improving creditor repayment prospects (e.g., Borchard and Hotchkiss 1951, Wynne 1951, Maurer 2013).

Account arrangements of the sort we identify, when used in full-recourse sovereign lending, can pose multiple policy challenges. First, they encumber scarce foreign exchange and fiscal revenues. Second, the encumbrance can be easy to hide. This follows from the fact that banks’ set-off rights against their account holders are usually found in background laws and regulations, and do not require a formal pledge, registration, or disclosure on the part of the debtor. Any additional contractual undertakings may also be kept confidential. In contrast, a lender that wishes to take effective security interest in a physical asset must enter into a separate agreement and make a public filing to get a priority claim against the asset. Third, undisclosed routing of revenue flows to special accounts impedes the accuracy of a debt sustainability analysis and multilateral surveillance work. If a substantial portion of a country's revenue streams is earmarked for the benefit of a single creditor, conventional measures of debt sustainability are likely to overestimate the country's true debt servicing capacity to all creditors. In balance of payments crises, this can undermine IMF programs, adding to the effective adjustment burden of the country and deepening haircuts for other creditors in the event of a debt restructuring. Fourth, control over revenue flows can give the lender considerable bargaining power vis-à-vis the debtor and other creditors, [27] which can translate into political leverage in the context of government-to-government lending.

Historical and contemporary experience with special accounts suggests that they may offer lenders limited, if any, protection. Cash-strapped debtors usually do not hesitate to redirect payment flows. However, it may be more difficult to do so if the creditor is also the source of those payment flows, as in the case with the oil-backed loan contracts discussed earlier. Special accounts may also help creditors deflect political pressure at home, reassuring shareholders and voters that risky debt would be repaid.

In contrast to the prevalence of special accounts, only 5 of the Chinese loans in our sample explicitly reference a formal security interest or pledge. In these cases, pledged assets include financial instruments (in Costa Rica and Honduras), mining rights (in the DRC), and project output and equipment, as well as shares in a project company (in Sierra Leone). We find little evidence in our contract sample that China's state-owned banks routinely use physical infrastructure—like a seaport or a power plant—as collateral. This finding stands in contrast to the prominent media and political narrative, which holds that China's lending practices are designed to appropriate strategic physical assets in poor countries (for a critique of this narrative, see Bräutigam and Kidane 2020).

The only debt contract in our sample that appears to entail a pledge of physical assets is for a syndicated loan from China Eximbank and ICBC to upgrade and expand a seaport in Sierra Leone. The contract contains several references to pledged collateral in the form of physical or financial assets that could be transferred to the lender and liquidated in the event of default. However, we were not able to obtain any of the security agreements referenced in this or any other contract in the Chinese sample, and do not have enough information to define the pledged assets or the operation of the collateral scheme with specificity.

In summary, Chinese lenders in our sample appear to prefer collateral in the form of bank accounts, with contractual minimum balance requirements to ensure that the lender would have cash to seize in the event of default. By comparison, collateral in the form of illiquid physical assets is more burdensome to secure and sell, harder to keep confidential, and more likely to draw unfavorable media coverage and political controversy.

Box 2. Use of collateral in Sierra Leone's port project loan with ICBC and China Eximbank

In 2017, ICBC and China Eximbank made a USD 659 million loan to Sierra Leone for the upgrade and expansion of Queen Elizabeth II Quay in Freetown. The borrower was National Port Development Sierra Leone Ltd., a special purpose vehicle (i.e., project company), which entered into a concession agreement with Sierra Leone's government to operate the port for 25 years. Although the parties used elements of a limited recourse project finance structure, the loan was fully guaranteed by the government of Sierra Leone.

The project company was established and is owned by Sky Rock Management Ltd., a private company incorporated under the laws of the British Virgin Islands. The loan's primary purpose is to finance the port expansion carried out by a consortium of Chinese engineering, procurement and construction firms.

Given the size of the loan (worth 15 percent of Sierra Leone's 2017 GDP), its high interest rates (LIBOR plus 3.5 percent p.a.) and the elevated political and economic risk in Sierra Leone, ICBC and China Eximbank made use of a variety of securitization mechanisms to mitigate default risk. The Facility Agreement references the following Security Documents:

-

Share Pledge Agreement: Sky Rock Ltd., the foreign investor, enters a share pledge agreement “in respect of their shares in the Borrower in favour of the Security Agent, in form and substance satisfactory to the Facility Agent” (p. 18). The Share Pledge Agreement is separate from the Facility Agreement and not publicly available, so it is unknown under what circumstances ownership in the project company could be transferred from the foreign investor to the creditors.

-

Mortgage over Assets: The Borrower enters a mortgage agreement over “equipment and other assets of the Borrower in relation to the Project […] in favour of the Finance Parties, in form and substance satisfactory to the Facility Agent” (p. 13). The Mortgage Agreement is separate from the Facility Agreement and not public, so it is unknown which assets are pledged.

-

Other security documents which evidence or create “security over any asset of the Borrower to secure any obligation of the Borrower under the Finance Documents” (p. 17). Since no other security documents are publicly available, no further details are known.

In addition to the Security Documents, the Facility Agreement also references an Account Agreement. Again, this is a separate document that is not publicly available. Cross references in the Facility Agreement show that ICBC and China Eximbank can designate “a bank outside the jurisdiction of Sierra Leone” at which the “Bank Accounts are opened and maintained” (p. 1). The conditions of utilization further reveal that the Borrower is required to transfer project revenue into this account so that the account balance at all times meets the minimum debt service coverage of “all principal scheduled to be paid and all interested expected to be payable under the Facility on the next Interest Payment Date” (p. 16).

In addition, the repayment of the loan is fully guaranteed by Sierra Leone's Ministry of Finance. In particular, the Ministry “guarantees to ensure that if […] the balance of the Borrower Collection Account falls to an amount that is less than is required to meet the next Scheduled Debt Service payment […], the Guarantor shall pay, or procure to be paid, into that account, such amount as may be necessary to ensure that the balance of the account is equal to the amount of the next Scheduled Debt Service payment” (p. 143).

Finally, the borrower is required to use part of the loan proceeds to purchase an insurance policy with Chinese state-owned Sinosure, which insures 95% of the facility plus accrued interest against political and commercial risk.

The figure below summarizes the financial and institutional structure of the deal. As can be seen, the parties involved are connected through a variety of contractual links. Contracts marked in grey have not been made public and are not available to us.

3.3 Seniority and “No Paris Club”: Chinese contracts enable lenders to seek preferential repayment without saying so

Only two debt contracts with China's state-owned banks formally claim senior status: an ICBC loan to Argentina and a collateralized loan from ICBC and China Eximbank loan to Sierra Leone, discussed earlier. On the other hand, all contracts in our Chinese sample commit the borrower to exclude the debt from any multilateral restructuring process, such as the Paris Club of official bilateral creditors, and from “comparable treatment” that the Paris Club requires the debtor to seek from its other creditors. Such a promise is unlikely to be enforceable in the court of any major financial jurisdiction; however, combined with other contract terms, it could give the lender more bargaining power in a crisis.

A typical “No Paris Club” clause in the Chinese contract sample is reproduced below:

[T]he Borrower hereby represents, warrants and undertakes that its obligations and liabilities under this Agreement are independent and separate from those stated in agreements with other creditors (official creditors, Paris Club creditors, or other creditors), and the Borrower shall not seek from the Lender any kind of comparable terms and conditions which are stated or might be stated in agreements with other creditors. [28]

Three CDB contracts with Argentina's Ministry of Economy contain an even more expansive variation on the theme:

The Borrower shall under no circumstances bring or agree to submit the obligations under the Finance Documents to the Paris Club for restructuring or into any debt reduction plan of the IMF, the World Bank, any other multilateral international financial institution to which the State is a part of, or the Government of the PRC without the prior written consent of the Lender. [29]

Comparability of treatment is one of six core Paris Club principles; it covers both commercial and official bilateral creditors that are not members of the Paris Club. [30] The stated objective of comparability is burden-sharing: governments are loath to grant relief if their taxpayers end up subsidizing other creditors instead of helping countries in distress. Comparability has long been a pillar of the international financial architecture, and has shaped international sovereign debt markets for decades (see Gelpern 2004; Schlegl, Trebesch and Wright 2019). In theory, a sovereign debtor that fails to secure comparable treatment from official or private non-Paris Club creditors risks losing its Paris Club relief, and potentially its IMF and other multilateral financing. In practice, no Paris Club treatment has ever been undone for lack of comparability, in part because it is assessed in the aggregate, treating all non-Paris Club creditors as a group, and defined loosely enough to accommodate a wide variety of creditor concessions.

A debtor that flouts the comparability principle and follows through on its preferential treatment promise to CDB or China Eximbank would be in serious breach of Paris Club norms, and would likely damage its relationships with the IMF, the World Bank, and other official and commercial creditors. As part of the Common Framework agreed in November of 2020, China and other G20 members that are not part of the Paris Club agreed to restructure their claims on the poorest sovereign borrowers in tandem with the Paris Club, implying broadly the same terms, including comparability of treatment for both official and commercial claims. Although the G20 statement is too vague to amount to a definitive commitment, it stands in tension with 74% of the Chinese contracts in our sample, which explicitly reject burden sharing with other creditors.

Box 3. The Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI

The G20 endorsement of a “Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI” suggests some progress toward greater alignment and coordination between China and other bilateral creditors, at least at the level of key principles. From this standpoint, it raises some hope that the divergence in contract behavior between China and other bilateral lenders could be narrowed or better reconciled in the years ahead.

The framework is a successor to the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), launched in April 2020 as a short-term measure to free up cashflows and help low-income countries respond to the COVID-19 shock. The Common Framework commits G20 governments to transparent negotiations among official creditors; seeking an obligation from borrowers to seek comparability of treatment across all creditors; and a common understanding of the key parameters for a debt treatment. In essence, the G20 text creates a Paris Club-like arrangement that includes China, without a move by the Chinese government to formally join the club itself.