Corridors of Power: How Beijing uses economic, social, and network ties to exert influence along the Silk Road

Abstract

This report analyzes Beijing’s efforts to cultivate economic, social, and network ties with 13 countries in South and Central Asia (SCA) over two decades. These ties foster interdependence with the PRC that have the potential to both empower and constrain SCA countries, while threatening to displace or diminish the influence of regional rivals such as Russia, India, and the United States. We marshal a robust set of qualitative and quantitative data to answer four critical questions: (i) How far does Beijing’s public diplomacy footprint extend within countries? (ii) To what extent does the PRC synchronize its economic and soft power tools in reinforcing ways? (iii) Is the PRC well-positioned to adapt its public diplomacy in the face of external shocks such as COVID-19? (iv) How do citizens in SCA countries view the PRC versus other great powers and do these attitudes diverge from their leaders? The answers to these questions provide an evidence base to inform contemporary debates about Beijing’s multi-dimensional influence playbook and how citizens respond to great powers jockeying for primacy in the region.

Executive Summary

Beijing’s bid for primacy in South and Central Asia (SCA) often generates heated rhetoric, rather than enlightened discussion, about how the People’s Republic of China (PRC) exerts influence, with whom, and to what ends. In this report, we analyze the PRC’s efforts to cultivate economic, social, and network ties with 13 countries over two decades. These ties foster interdependence with the PRC that have the potential to both empower and constrain SCA countries, while threatening to displace or diminish the influence of regional rivals such as Russia, India, and the United States. We look deeper than national boundaries to examine which communities receive the lion’s share of Beijing’s attention. Finally, we consider how the PRC has navigated the conversion dilemma of translating economic and soft power investments into favorability with SCA leaders and publics—as an end in itself and an instrument to advance other goals.

Four takeaways about how Beijing builds economic ties in the region

In this report, we examine how the PRC has deployed US$127 billion in financial diplomacy across the SCA region to sway popular opinion and leader behavior in SCA countries over an 18-year period. This state-directed financing includes both aid (i.e., grants and concessional loans) and debt (i.e., non-concessional loans approaching market rates) in four categories of assistance visible to foreign publics (infrastructure financing, humanitarian aid) and prized by foreign leaders (budget support, debt relief). If we look beyond national boundaries, the PRC clearly views some communities as more strategically important to advancing its interests than others. Specifically, we identify four takeaways about how Beijing deploys its financial diplomacy between and within countries across the region:

-

Beijing employs three distinct subnational public diplomacy strategies—”extract,” “nudge,” and “avoid”—varying its engagement to best advance economic, security, and geopolitical goals.

-

Its financial diplomacy is highly concentrated: it focuses the lion’s share of its state-directed financing to just 25 provinces (62 percent of financing) and 25 districts (41 percent of financing) in the region.

-

More populous districts and those with natural gas pipelines are the most likely recipients of Chinese financial diplomacy dollars.

-

Pakistan’s shipping corridors and pipelines attract nearly one-third of the PRC’s financial diplomacy across SCA countries, fostering economic ties with local, national, and regional implications.

Four takeaways about how Beijing builds social ties in the region

Although the PRC is best known for the power of its purse, Beijing’s economic and soft power tools may be most formidable in exerting influence with SCA countries when they are employed in concert. As SCA countries become economically integrated and connected with the PRC, the more open they may become to embracing Chinese language, culture, and norms. The more that SCA publics and elites build closer people-to-people ties with counterparts in China, the more they may turn to these social networks when it comes to sourcing goods, services, capital, and other economic partnerships. In the report, we examine how Beijing employs education, language, and city diplomacy to socialize SCA professionals to Chinese norms, technologies, and systems to create future markets for PRC goods, services, and capital. Looking across these data points, we identify four takeaways about how Beijing builds social ties:

-

Beijing’s education assistance projects have increasingly emphasized scholarships, technical assistance, and training as a pipeline to feed into its higher education institutions.

-

The PRC offers less burdensome requirements, numerous scholarships, English language curricula, and new training modalities to become a premier study abroad destination.

-

Russia, India, and the US have a longer-standing presence, but the PRC now accounts for 30 percent of language and cultural institutions in the SCA region, only surpassed by the US.

-

Beijing has cultivated 193 central-to-local or local-to-local ties with 174 cities across the SCA region, but over half of all ties (52 percent) were focused on just 16 priority cities.

Four takeaways about how Beijing builds network ties in the region

Although banned in China, PRC leaders have harnessed tools such as Twitter abroad to amplify narratives they prefer and contest those which run counter to their interest. However, this strategy relies on access to SCA elites—either directly or indirectly, via those with whom they are connected. In the report, we assess the PRC’s ability to reach SCA elites on Twitter that: (i) can directly make decisions of consequence for Beijing or (ii) by virtue of their organizational position, national prominence, or professional reputation can indirectly influence their peers and leaders. We analyze connections between 2,273 Twitter accounts from 12 SCA countries that meet our inclusion criteria and 115 PRC-affiliated accounts associated with: embassies, consulates, or diplomatic staff in SCA countries; state-run media outlets; state-owned enterprises working in SCA countries; and other PRC government agencies with an external-facing presence. We highlight four take-aways about Beijing’s efforts to build network ties with SCA elites in the region:

-

PRC engagement on Twitter is heavily centralized, with a small number of brokers serving as access nodes to reach broader networks of SCA elites and vice versa.

-

PRC accounts engage most actively with Pakistani accounts, suggesting that China is pairing offline engagement through CPEC with online engagement.

-

State-owned media are the PRC’s frontline representatives pushing out information to SCA elites; diplomatic accounts are gatekeepers and amplifiers.

-

PRC-affiliated accounts might be more frequently followed, but Indian accounts are more frequently mentioned by other Twitter users.

Four takeaways about citizen and leader perceptions of Beijing

In the report, we examine what a nationally representative citizen survey—the Gallup World Poll (2006-2020)—can tell us about perceptions of the PRC over time and relative to its three strategic competitors in the region: India, Russia, and the US. Using a set of statistical models, we test whether and how Beijing’s public diplomacy tools may translate into improved popular perceptions in SCA countries. Finally, we leverage a 2021 AidData snap poll survey of SCA elites to assess the degree to which their views converge or diverge with the public, as well as how they view the public diplomacy efforts of four great powers active in the region. Triangulating these data points yields four takeaways about how citizens and leaders view Beijing:

-

SCA citizens fall into three groups in their views of the PRC: consistently favorable (Pakistan and Tajikistan), consistently unfavorable (India), and middle-of-the-road (everyone else).

-

Beijing’s financial diplomacy is associated with lower approval of Russia, higher approval of the US, and mixed views of China. It is positively associated with approval of the PRC only in those countries which receive more financing relative to other forms of public diplomacy.

-

In general, SCA citizens were more favorable towards Russia and the PRC, while their leaders were more favorable towards India and the US.

-

Economic opportunity drives how SCA leaders view the PRC and the US; they suggest increased financial diplomacy and people-to-people ties to boost standing in future.

Three cross-cutting insights about Beijing’s influence playbook

In this report, we assess the PRC’s use of economic statecraft, people-to-people diplomacy, and digital diplomacy in concert, rather than in isolation, to understand how they add up to more than the sum of their parts. It is clear that Beijing has doubled down on its efforts to cultivate economic, social, and network ties with SCA countries over the last two decades. Nevertheless, Beijing’s ability to translate these inputs into realized influence that advances its national interests is not inevitable. It must navigate some fierce headwinds at home, with anti-China skeptics within SCA countries, and from its strategic competitors such as Russia, India, and the US who are keen to avoid seeing their influence in the region displaced by a PRC bid for primacy. Taking the long view, there are three cross-cutting insights about Beijing’s influence playbook over the last two decades worth highlighting:

-

Beijing’s ability to synchronize multiple economic and soft power tools in its playbook is a comparative advantage in its bid for regional influence.

-

Beijing’s public diplomacy overtures cultivate narrow but deep corridors of power, focusing attention on a small subset of strategically important communities.

-

Economic opportunity and people-to-people ties may go together, but Beijing’s ability to convert public diplomacy inputs into realized influence is easier said than done.

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by Samantha Custer, Justin Schon, Ana Horigoshi, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Vera Choo, Amber Hutchinson, Austin Baehr, and Kelsey Marshall (AidData, William & Mary). The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders and contributors we thank below.

John Custer and Parker Kim were instrumental in creating high-impact visuals and along with Soren Patterson conducted the final formatting, layout, and editing of this publication. Bryan Burgess made an important contribution through providing the cross-walked data for financing against the Sustainable Development Goals that supported our analysis of donor-leader-citizen alignment of development priorities. Phil Roessler and Rob Blair were invaluable in the design and preliminary analysis of two conjoint survey experiments featured in this report.

Rodney Knight supported the research design and quality assurance process to ensure our methods were appropriate to the task at hand and the results carefully verified for accuracy. Christian Baehr oversaw the process of geo-referencing our data to allow us to gain more granular insights on the breadth and depth of China’s overtures at the subnational level. Ammar A. Malik provided helpful feedback on the findings and conclusions. We thank the respondents who graciously answered our snap poll survey questions, sharing their insights on their perceptions of foreign powers across the South and Central Asia region, their views of these powers’ public diplomacy efforts, and their level of current and desired foreign language proficiency. We appreciate several subject matter experts who shared their time and insights with us in background interviews in preparation for this report. Our AidData Communications team—John Custer, Sarina Patterson, and Parker Kim—were instrumental in creating high-impact visuals, along with the final formatting, layout, and editing which we hope make this report more engaging for you to read.

As the second report in this series on China’s influence in South and Central Asia, we stand on the shoulders of colleagues who helped collect and analyze the preliminary data on China’s public diplomacy that offer an empirical foundation for this report. We owe a debt of gratitude for their efforts, including to: Tanya Sethi, Jonathan A. Solis, Joyce Jiahui Lin, Siddhartha Ghose, Anubhav Gupta, Katherine Walsh, Brooke Russell, Molly Charles, Steven Pressendo, Wenyang Pan, Paige Jacobson, Ziyi Fu, Kathrynn Weilacher, Caroline Duckworth, Xiaofan Han, Carlos Holden-Villars, Mengting Lei, Caroline Morin, Wenzhi Pan, Richard Robles, Yunji Shi, Natalie White, Fathia (Fay) Dawodu, Carina Bilger, Raul De La Guardia, Xinyao Wang, and Lincoln Zaleski. In addition, we drew upon an expanded team of research assistants to support a range of supplemental data collection that added new insights to this second report, including: Hanna Borgestedt, Riley Busbee, Megan Steele, Mikayla Williams, Sarah Dowless, Claudia Segura, Alondra Belford, Eric Brewer, Daniel Brot, Grace Bruce, Gabriella Cao, Makayla Cutter, Cassie Heyman-Schrum, Maureen Lewin, Holden Mershon, Noelle Mlynarczyk, Ankita Mohan, Cassie Nestor, Grace Riley, Christopher Rossi, Dongyang Wang, Rachel Yu, Merielyn Jiangcheng Sher, Xiatian Kate Chu, Isaac Poritzky, Nawate Wani, Lena Zheng, Keely Wiese, Wanggxinyi Freda Deng, Yingyue Abi Xu, Sihan Michelle Zhou, Fei Wu, Shan Kelly Gao, Rui Ray Shen, Yuchieh Cheng, Xinyao Louise Lin, Jessica Yongyi Liu, and Jacob Barth.

This report was made possible through generous support from the United States Department of State and the Ford Foundation. We would also like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the Asia Society Policy Institute and the China Power Project of the Center for Strategic and International Studies to an earlier phase of in-country interviews and a related report, Silk Road Diplomacy, that provided an important intellectual foundation for this second phase of work.

Citation

Custer, S., Schon, J., Horigoshi, A., Mathew, D., Burgess, B., Choo, V., Hutchinson, A., Baehr, A., and Marshall K. (2021). Corridors of Power: How Beijing uses economic, social and network ties to exert influence along the Silk Road. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at the College of William & Mary.

Figures and Tables

Figures

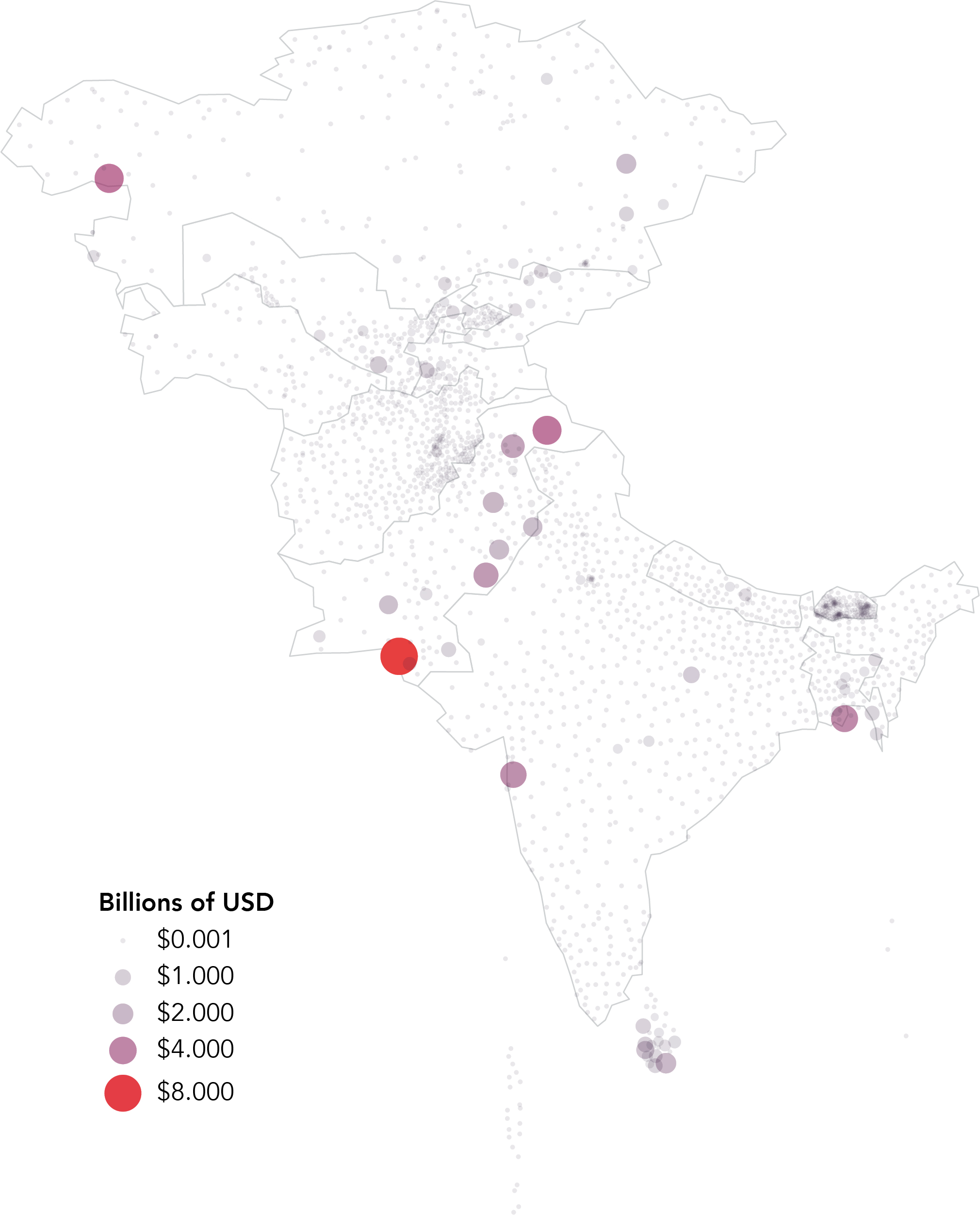

- Figure 1. Beijing’s financial diplomacy by SCA country, 2000-2017

- Figure 2. Beijing’s subnational financial diplomacy by SCA country, 2000-2017

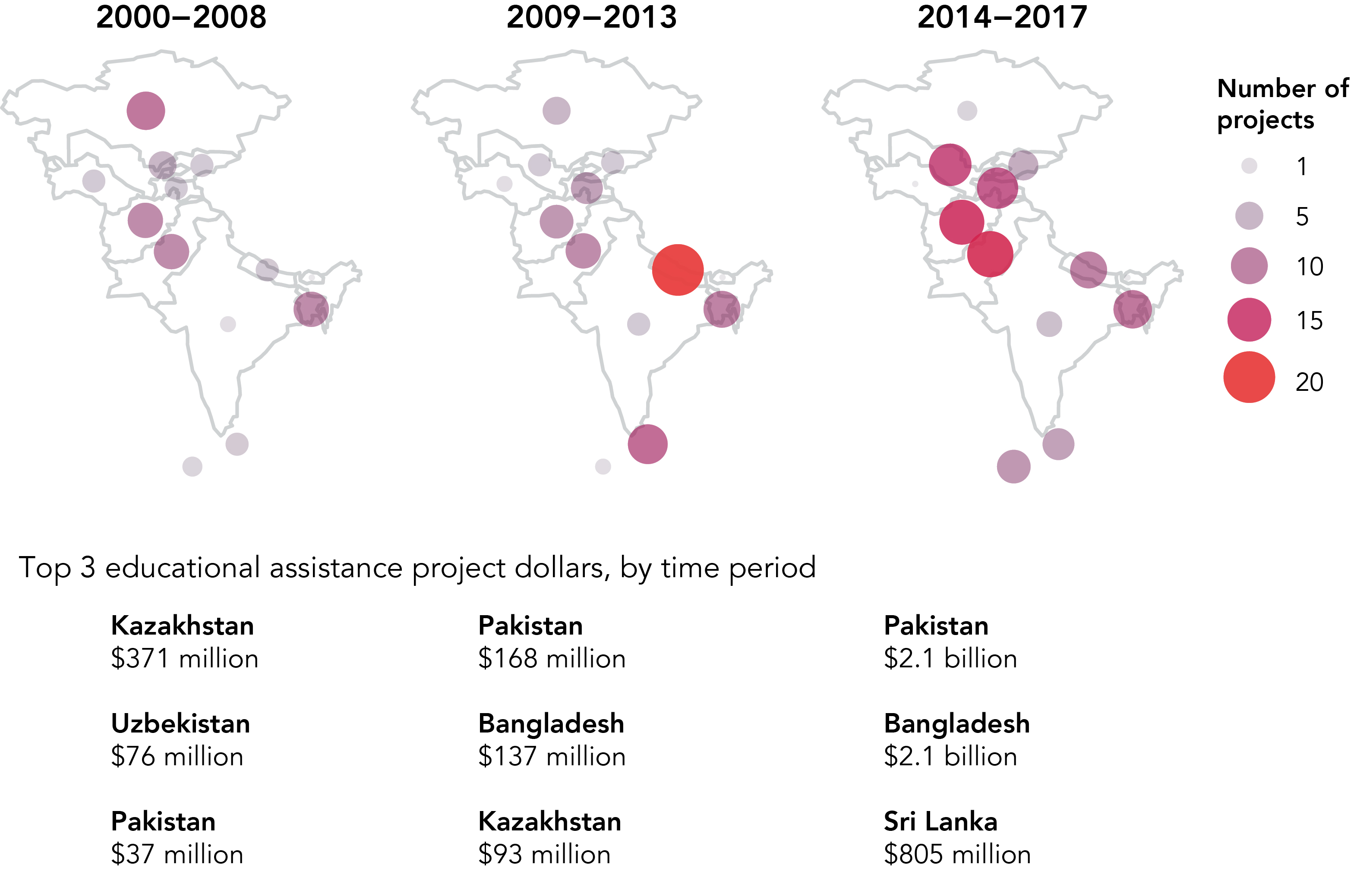

- Figure 3. Geographic distribution of educational assistance project counts, by country and time period

- Figure 4. SCA students studying abroad in China annually by country, 2010-2017

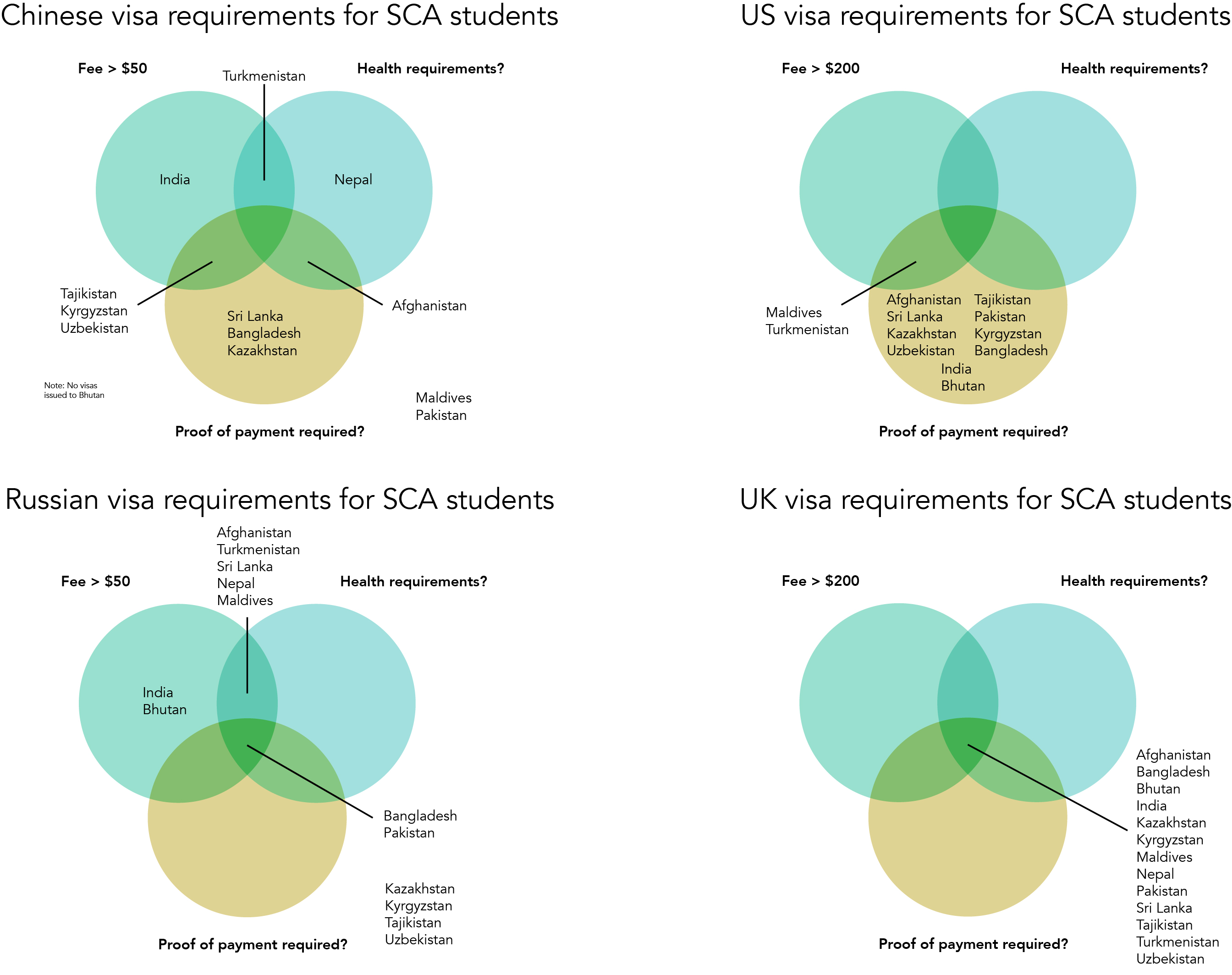

- Figure 5. Comparative visa requirements for SCA students in the PRC, Russia, the US, and the UK

- Figure 6. Cumulative number of American Spaces and Confucius Institutes in South and Central Asia, 2000-2018

- Figure 7. Language and culture centers run by Russia, China, and the US

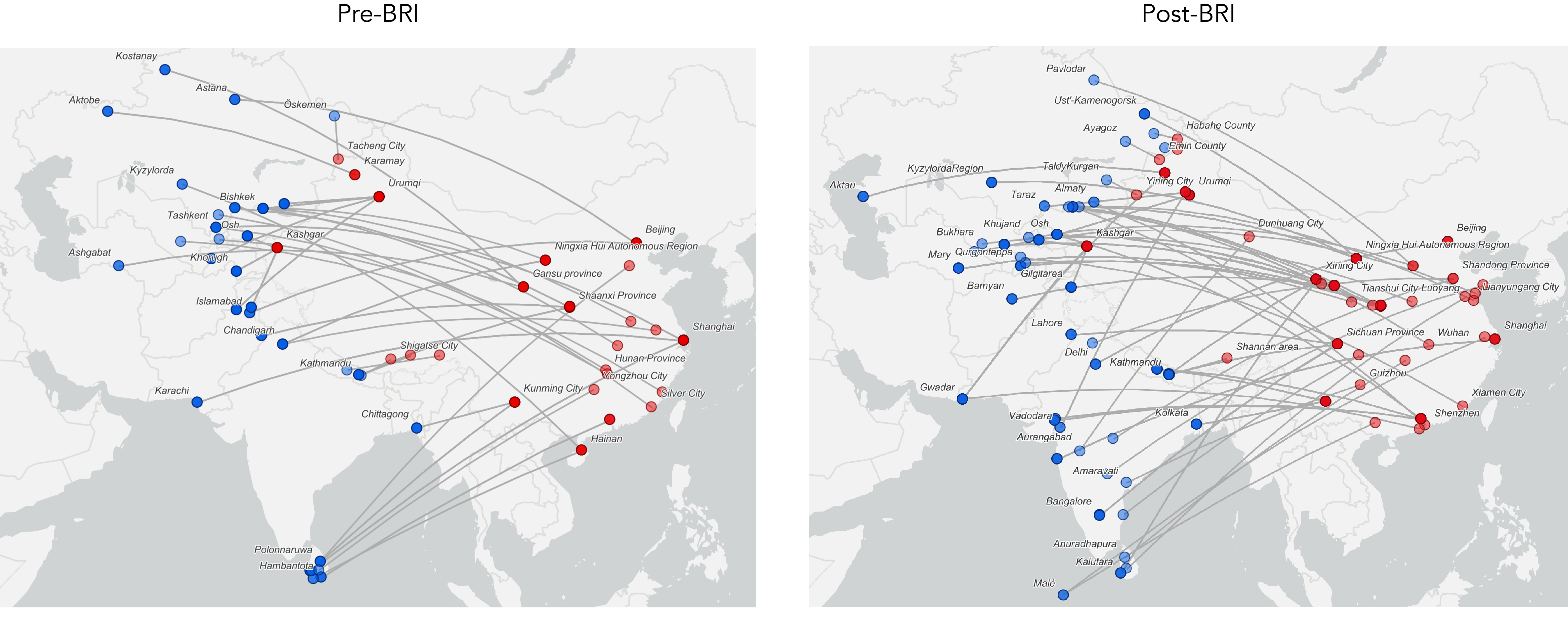

- Figure 8. Sister city relationships between the PRC and SCA countries, 2000-2018

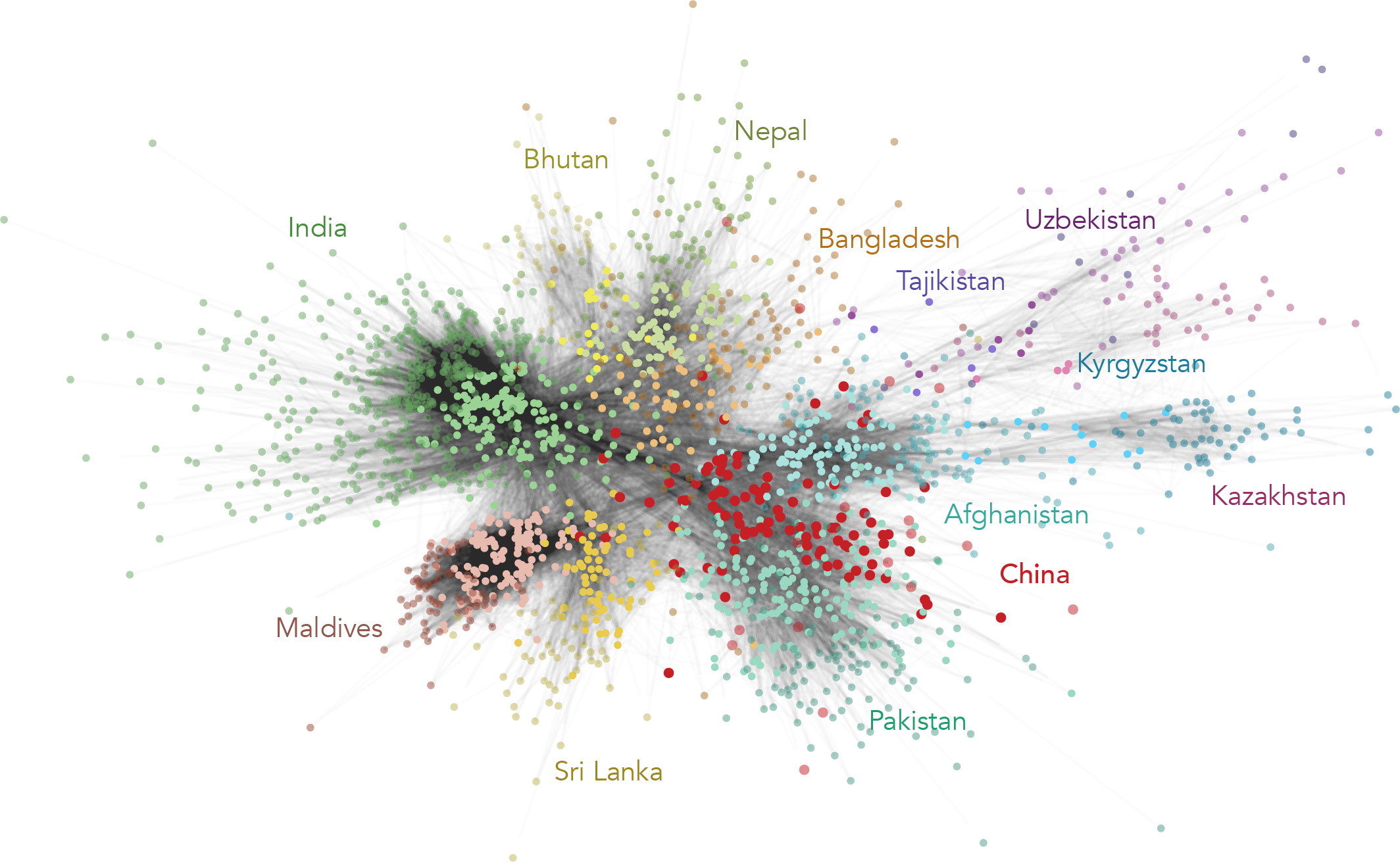

- Figure 9. Sample of SCA and PRC elites on Twitter, by country

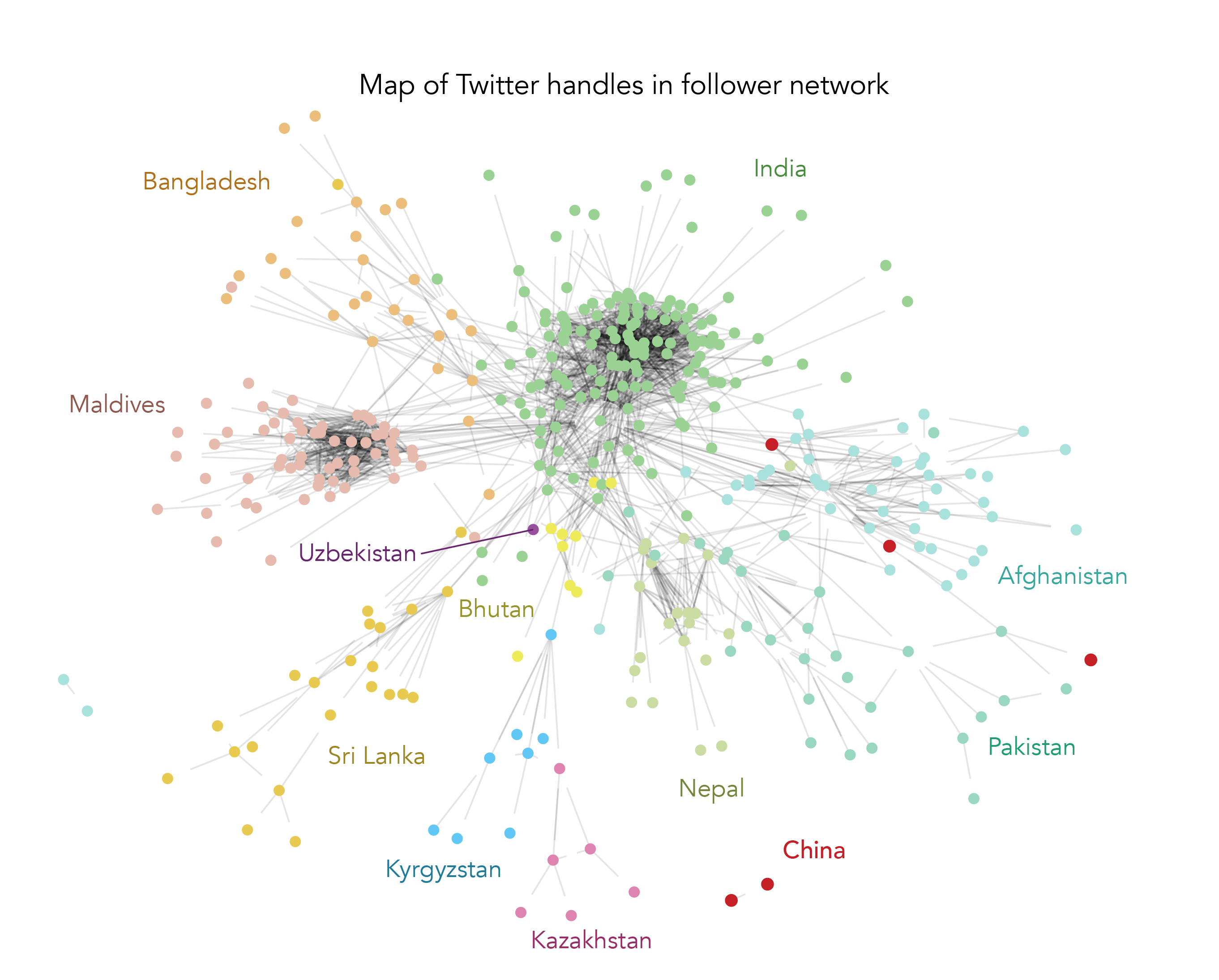

- Figure 10. How connected is a country’s social network on Twitter?

- Figure 11. Distribution of connections for handles from a given country

- Figure 12. How connected are SCA and PRC elites on Twitter?

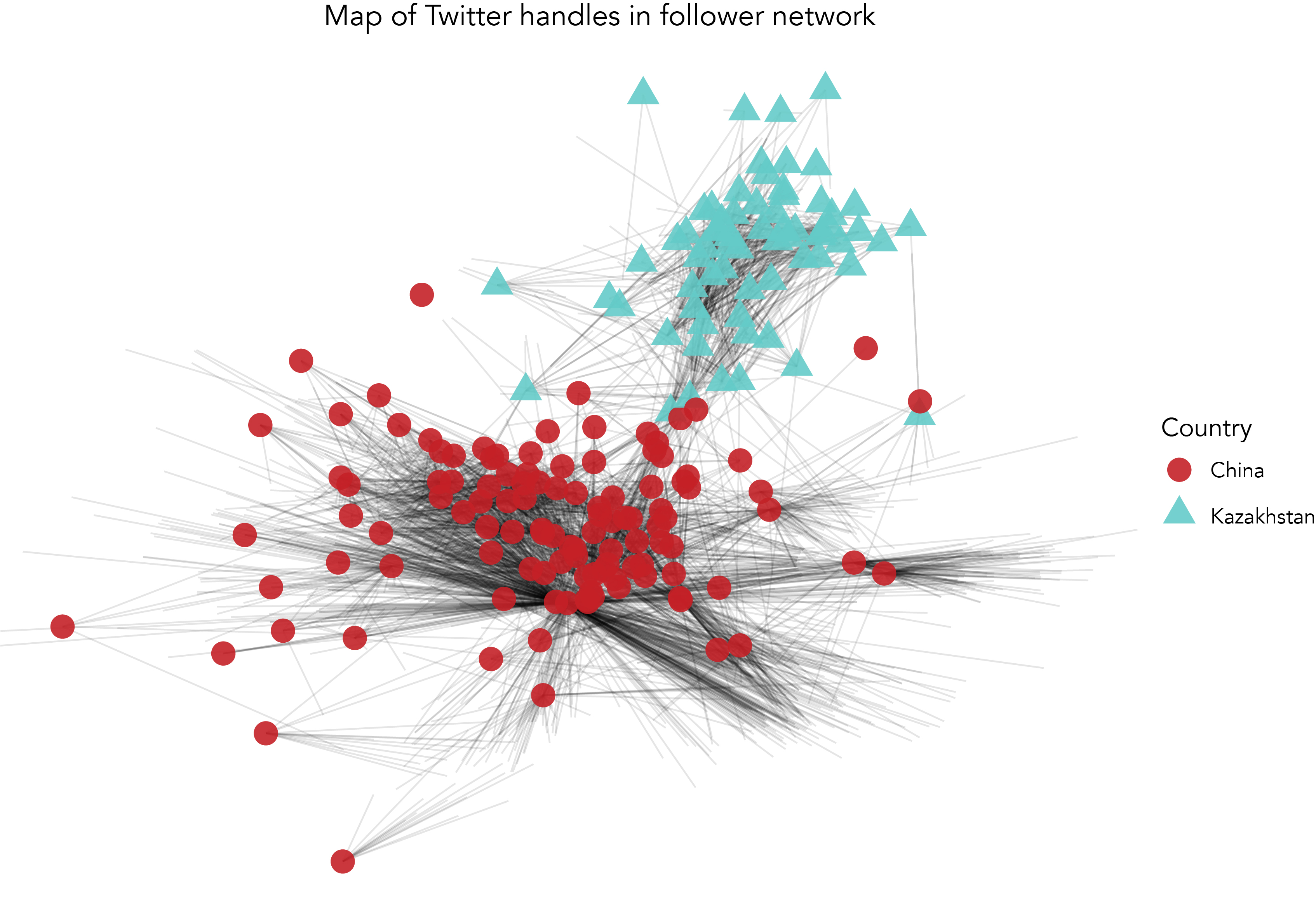

- Figure 13. How connected are Kazakhstan and PRC Twitter communities?

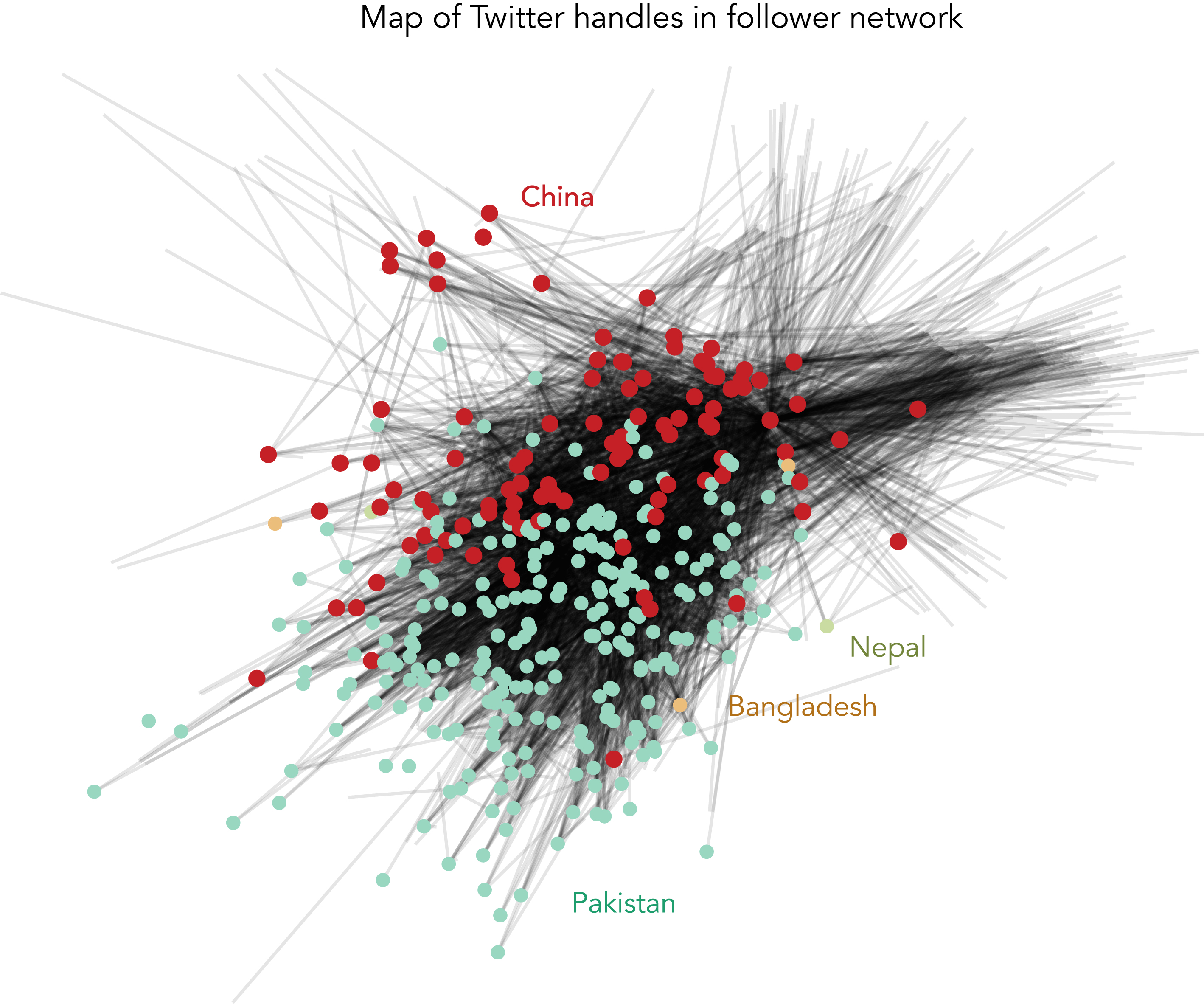

- Figure 14. How connected are Pakistan and PRC Twitter communities?

- Figure 15. To what extent do SCA and PRC elites mention each other on Twitter?

- Figure 16. Distribution of mentions across Twitter handles, by country

- Figure 17. SCA citizen approval rates of foreign powers, 2006-2020

- Figure 18. Relationship between high-level visits by PRC leaders and SCA citizen approval rates

- Figure 19. Elite perceptions of the PRC versus strategic competitors in SCA, 2021

- Figure 20. Reasons why elites held favorable attitudes towards the US and PRC, 2021

- Figure 21. Activities elites associate with foreign powers in their country, 2021

- Figure 22. Which foreign power did elites view as adapting their public diplomacy most effectively to COVID-19?

- Figure 23. Areas SCA elites suggest the US and PRC should focus on to improve favorability

Tables

- Table 1. Beijing’s three subnational public diplomacy strategies: Extract, nudge, avoid

- Table 2. Possible factors driving Beijing’s financial diplomacy allocations

- Table 3. Number of educational assistance projects, by country and time period

- Table 4. Number of PRC educational assistance projects by category, all SCA countries, 2000-2017

- Table 5. PRC state-backed scholarships for SCA students studying in China

- Table 6. Indian government scholarship programs in which SCA countries are named

- Table 7. Number of Chinese top-tier HEIs offering English or Russian medium of instruction, by institution type

- Table 8. Total number of Confucius Institutes and Classrooms in SCA countries, 2004-2018

- Table 9. Language and cultural centers of PRC and rival powers in the SCA region, 2018

- Table 10. Reported fluency and interest in English, Mandarin, and Russian, snap poll survey responses, 2021

- Table 11. Two types of socio-cultural ties at the city or province level

- Table 12. Top 16 cities by touchpoints to the PRC

- Table 13. Key concepts in understanding Twitter network analysis

- Table 14. Differentiating between four types of brokers

- Table 15. Top PRC representatives interacting with SCA elites

- Table 16. Top PRC gatekeepers interacting with SCA elites

- Table 17. Top SCA gatekeepers for each country

- Table 18. Top SCA representatives by country

Acronyms

BRI: Belt and Road Initiative

CCP: Chinese Communist Party

CCTV: China Central Television

CGTN: China Global Television Network

CI: Confucius Institute

CPEC: China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

CRI: China Radio International

GWP: Gallup World Poll

HEIs: Higher Education Institutions

HSK: Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi

ICCR: India Council for Cultural Relations

IPI: Iran-Pakistan-India Pipeline

MEA: Ministry of External Affairs, India

PRC: People’s Republic of China

PSGP: PakStream Gas Pipeline

SCA: South and central Asia

TAPI: Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India

UK: United Kingdom

US: United States

Chapter one Introduction

In July 2021, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) joined five South Asian countries to launch new platforms to orchestrate regional cooperation on COVID-19 vaccination, climate change, and poverty alleviation (Ghimire and Pathak, 2021; Gautam, 2021). [1] Missing was Beijing’s proximate rival for influence in South Asia—India. The fanfare of the PRC-led cooperation prompted unflattering comparisons to the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), hampered by unresolved disputes between India and Pakistan (Agarwal, 2021; Giri, 2021). Earlier in May 2021, PRC Foreign Minister Wang Yi announced with five Central Asian counterparts a series of cooperative initiatives—from agriculture and education to cultural heritage and traditional medicine (Devonshire-Ellis, 2021; China MFA, 2021). He also sought to cast the PRC as an ally supporting reconstruction in Afghanistan and laid ground for the country to join the China-Central Asia (C+C5) bloc, in which Russia is noticeably absent, in future (ibid).

Both episodes illustrate Beijing’s healthy appetite to win over foreign leaders and publics in what the PRC considers its “greater periphery” (Li and Yuwen, 2016). Moreover, they spotlight Beijing’s multidimensional influence playbook as it seeks closer economic, social, and network ties with South and Central Asian (SCA) countries to advance its national interests. Public diplomacy refers to a collection of instruments used to influence the perceptions, preferences, and actions of foreign leaders and citizens. This includes efforts to export culture and language, foster people-to-people ties, cultivate relationships with other leaders, shape media narratives, and employ the power of their purse to win friends and influence people. These ties foster interdependence between economies and societies that present both opportunities and vulnerabilities (Nye, 2021).

This bid to exert influence is not new; PRC leaders have long viewed the thirteen SCA countries as a geostrategic priority and a fulcrum of power (Scobell et al., 2014). Over the past two decades, Beijing has employed the full range of its economic and soft power tools to manage negative reactions in SCA countries to its growing military and economic might, while building a coalition of countries willing to back its preferred policy positions in international fora. Doshi (2021) describes PRC leaders as playing a “long game” to displace status quo powers in a bid for regional and global hegemony that has grown in assertiveness over time. Beijing’s aims may be long-standing, but its strategy—the intentional, synchronized use of multiple tools of statecraft to advance national interests—has evolved in response to perceived threats and the relative strength of its strategic competitors (ibid).

There are some indications that Beijing’s “charm offensive” may be returning dividends (Kurlantzick, 2007). The PRC was rated among the top ten most influential development partners in a 2020 survey of nearly 7,000 leaders, making its greatest inroads with respondents in the Asia-Pacific (Custer et al., 2021a). [2] Its efforts to cultivate sympathetic local media (e.g., journalist exchanges, op-eds and interviews in SCA media) have been associated with more favorable views of PRC leadership and a chilling effect on critical coverage of Beijing’s policies (Custer et al., 2019a and 2019b). In addition, countries that received more attention from Beijing, particularly in the form of visits from PRC elites, and financing on generous terms tended to have lower rates of disapproval of PRC leadership (ibid).

Yet, Beijing’s willingness to bankroll an ambitious public diplomacy program has provoked mixed reactions in SCA countries. Some value Beijing’s attention and investments in their economy, viewing its development story as one to which they aspire and an opportunity to assert independence from status quo regional powers such as India and Russia. For others, the PRC’s bid for influence recalls tales of debt distress, quid pro quo dealings, and being pulled into a geostrategic tug of war between great powers in an era of heightened competition. Moving from marshalling inputs to achieving one’s desired outcomes is neither straightforward, nor quick. Nye (1990; 2003) calls this the “paradox of power”: countries with the greatest resources or capabilities (potential power) do not always get the outcomes they want (realized power). The PRC must overcome a conversion dilemma—the ability to influence changes in public attitudes and leader behavior in ways that align with their objectives (ibid).

In 2019, AidData, a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute, collected and analyzed data to understand how Beijing deployed five public diplomacy instruments—financial, information, cultural, exchange, and elite-to-elite diplomacy—to shape public opinion and leader behavior in 13 SCA countries (Custer et al., 2019a). Using a mixed methods approach, the authors shed light on which tools Beijing used, with whom, and to what end. They also sought to understand how public diplomacy might advance Beijing’s national interests—from more favorable popular perceptions to discrete economic, foreign policy, and security concessions.

The first report answered some questions but raised new ones. In parallel, the arrival of the COVID-19 global pandemic provided new avenues for competition between states jockeying for influence and constraints in using conventional public diplomacy. In this second report, we marshal a robust set of qualitative and quantitative evidence to answer four questions: (i) How far does Beijing’s public diplomacy footprint extend within countries, beyond a small number of elites in capital cities? (ii) To what extent does the PRC synchronize its tools to foster economic, social, and network ties in reinforcing ways? (iii) Is the PRC well-positioned to adapt its public diplomacy in the face of external shocks such as COVID-19? (iv) How do citizens in SCA countries view the PRC versus other great powers and do these attitudes diverge from their leaders?

1.1 Exerting influence via economic, social, and network ties

The remainder of the report is organized in six chapters. In Chapter 2, we examine financial diplomacy—a subset of state-directed overseas aid and debt instruments aimed towards advancing diplomatic objectives—as the cornerstone of Beijing’s influence strategy. Economic opportunity is routinely cited as an explanation for what attracts countries to engage with the PRC. This is true of leaders who see infrastructure as the gateway to economic growth for their countries and Beijing as the most likely partner in that endeavor, as well as for citizens that see the PRC as important to their livelihood prospects—in creating jobs, offering capital, or brokering connections. Nevertheless, these economic ties can constrict autonomy of action, creating explicit or implicit obligations to back Beijing’s preferred policies, avoid criticism of its actions, and grant financial, political or security concessions. We examine how the PRC has deployed its financial diplomacy over nearly two decades not only between but also within countries and what these growing economic ties may mean for Beijing’s strategic competitors.

China’s cultural distance from SCA countries may hinder uptake of Chinese language and norms, but economic cooperation could create sufficient enticement—increasing the gravitational pull of the prospective rewards—to change that status quo. As SCA countries become economically integrated and connected with the PRC, the more open they become to embracing Chinese language, culture, and norms. Relatedly, the more that SCA publics and elites build closer people-to-people ties with counterparts in China, the more likely they turn to these social networks when it comes to sourcing goods, services, capital, and other economic partnerships. In Chapter 3, we examine how the PRC leverages a combination of tools such as educational cooperation and student exchange, and language and cultural promotion, along with city level diplomacy to stoke these closer social ties. We also compare the PRC’s efforts versus those of other foreign powers.

Although social media tools such as Facebook and Twitter are banned in China, PRC leaders have harnessed these tools abroad to amplify narratives they prefer and contest those which run counter to their interest. In a social media network, access to other users is a form of communicative power (Cooley et al., 2020) to propagate one’s preferred messages or counter those in opposition, to one’s advantage. In Chapter 4, we examine PRC-affiliated individuals and organizations on Twitter as a window into state-orchestrated storytelling, as these individuals must not run afoul of Beijing’s censorship rules. Specifically, we are interested in the PRC’s ability to reach not just anyone on Twitter, but a particular set of public, private, and civil society elites in SCA countries that either: (i) can directly make decisions of consequence for Beijing or (ii) by virtue of their organizational position, national prominence, or professional reputation can indirectly influence their peers and leaders within SCA countries.

One of Beijing’s stated ends for its public diplomacy is to win the admiration of the world for China’s culture, language, and civilization following a “century of humiliation”(Tischler, 2020)—and perceived favorability with citizens in SCA countries is a reasonable proxy. Also, the degree to which citizens and leaders view the PRC favorably could be instrumental to advance other economic, geopolitical, and security interests. Higher favorability ratings may indicate greater appreciation for economic or security cooperation between countries, as well as closer affinity with a foreign powers’ norms, rules, and values. In Chapter 5, we examine what a nationally representative citizen survey and a snap poll of public, private, and civil society leaders can tell us about perceptions of the PRC and its public diplomacy overtures, both in absolute terms and relative to its three strategic competitors in the region: India, Russia, and the United States (US).

Pivotal events such as the 2008 global financial crisis, the 2013 announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative, and the 2020 outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, among others, have been inflection points in the PRC’s relationships with SCA countries. Moreover, the last two decades have been marked by heightened competition, as the PRC has sought to expand its hegemony in Asia at a time when it sees rival powers weakened. This report takes this historical perspective—assessing the cumulative inputs and outcomes of Beijing’s efforts spanning nearly two decades to foster economic, social, and network ties with SCA countries —to inform contemporary debate regarding how citizens respond to the “long game” of great powers jockeying for primacy in the region (Doshi, 2021). In Chapter 6, we conclude with a discussion—of the implications from this study for SCA countries, the PRC, and its strategic competitors during what some call a “critical juncture” in Beijing’s bid for leadership of the post-COVID international order (Ameyaw-Brobbey, 2021; Campbell and Doshi, 2020)—that has national, regional, and global consequences.

Chapter two Economic ties: How wide and deep is Beijing’s financial diplomacy footprint among South and Central Asian communities?

Key findings in this chapter:

-

Beijing employs three distinct subnational public diplomacy strategies—“extract,” “nudge,” and “avoid”—varying its engagement to best advance economic, security, and geopolitical goals.

-

Beijing’s financial diplomacy is highly concentrated: it focuses the lion’s share of its state-directed financing to just 25 provinces (62 percent of financing) and 25 districts (41 percent of financing) in the region.

-

More populous districts and those with natural gas pipelines are the most likely recipients of Chinese financial diplomacy dollars.

-

Pakistan’s shipping corridors and pipelines attract nearly one-third of the PRC’s financial diplomacy across SCA countries, fostering economic ties with local, national, and regional implications.

The Chinese government directed US$127 billion in financial diplomacy—the cornerstone of Beijing’s efforts to sway popular opinion and leader behavior—across 865 projects in the South and Central Asia region between 2000 and 2017 (Custer et al., 2019a). [3] This state-directed financing included both aid (i.e., grants and concessional loans) and debt (i.e., non-concessional loans approaching market rates) in four key categories of assistance visible to foreign publics (infrastructure financing, [4] humanitarian aid [5]) and prized by foreign leaders (budget support, [6] debt relief [7]). Although it includes projects featuring various financing terms and categories of assistance, the preponderance of Beijing’s financial diplomacy dollars to the region was debt financing (74 percent) and oriented to infrastructure investments (95 percent). [8]

In the remainder of this chapter, we examine how Beijing has wielded financial diplomacy over nearly two decades (2000-2017) to cultivate economic ties to advance its national interests across South and Central Asian countries (section 2.1). We explore how wide and deep these financial diplomacy investments appear to reach within countries and possible explanations for why some communities have attracted more of Beijing’s financing than others (section 2.2). Finally, we examine the case of Pakistan to assess what these growing economic ties may mean for Beijing’s strategic competitors, such as the US, Russia, and India, and for countries on the receiving end of these overtures (section 2.3).

2.1 Following the money: Beijing’s financial diplomacy across countries

Looking across the region, there is a clear pecking order in terms of the countries that garner the lion’s share of Beijing’s financial diplomacy (Figure 1). Two countries—Pakistan and Kazakhstan—accounted for 56 percent of Beijing’s financial diplomacy during the period, receiving US$39 billion [9] and US$33 billion, respectively. Much of this state-directed investment was concentrated in relatively few outsized investments such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and Kazakhstan’s portion of the China-Central Asia Gas Pipeline. Over a quarter (26 percent) of Beijing’s financial diplomacy was directed towards three countries: Sri Lanka (US$13 billion), Bangladesh (US$11 billion), and Turkmenistan (US$9 billion). Beijing split the remaining 18 percent of its financial diplomacy across the remaining seven countries.

Beijing does not use a one-size fits all strategy, demonstrating a clear preference for disproportionately funneling financial diplomacy investments to some countries over others. Previously, Custer et al. (2019) found that SCA countries with a larger share of Chinese firms and migrants, as well as those with lower internet penetration, were more likely to attract Beijing’s financial diplomacy than their regional peers. In this report, we zoom in and shift our focus from country boundaries to the local level, finding evidence that the volume and composition of Beijing’s public diplomacy overtures not only vary between, but also within, SCA countries.

Notes: This graph visualizes the PRC’s total financial diplomacy to SCA countries from 2000 to 2017. Consistent with Custer et al. (2019a), financial diplomacy includes commitments for infrastructure, budget support, debt relief, and humanitarian assistance. Financial figures are represented in constant USD 2017.

Source: Custer et al. (2019a).

Finding #1. Beijing employs three distinct subnational public diplomacy strategies—”extract,” “nudge,” and “avoid”—varying its engagement to best advance economic, security, and geopolitical goals.

Using hierarchical clustering analysis based on nearly two decades of data on Beijing’s financial, cultural, and exchange diplomacy at the subnational level, we find that the PRC has historically practiced divergent strategies—”extract,” “nudge,” and “avoid”—for how it has engaged local communities within three groups of countries (Table 1). [10] Three countries (Turkmenistan, Bhutan, Maldives) and two public diplomacy tools (information and elite-to-elite visits) were dropped from this clustering analysis due to insufficient variation.

|

Strategy |

Description |

Countries included |

|

Extract |

Relative emphasis on financial diplomacy over cultural and exchange at the local level. Prioritizes extraction in the form of access to energy supplies and strategic positioning for transit. routes. These countries appear to be mostly within Russia’s sphere of influence. |

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan |

|

Nudge |

Relative emphasis on cultural and exchange diplomacy, over financing, at the local level. Prioritizes soft power efforts to nudge local communities to view China more favorably. These countries appear to be mostly within India’s sphere of influence. |

India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh |

|

Avoid |

Minimal levels of public diplomacy overall, oriented towards the capital city, with minimal financial, cultural or exchange diplomacy at the local level. Until the withdrawal of US troops in mid-2021, somewhat oriented towards US influence. |

Afghanistan |

Notes: For more information on the hierarchical clustering analysis that informed the creation of these groups, see the technical appendix. Bhutan, Maldives, and Turkmenistan were dropped from the clustering analysis due to insufficient variation in their allocations.

With six countries in the region—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, Pakistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan—PRC leaders have historically employed an extraction strategy at the local level, heavily weighted towards financial diplomacy. Although the six countries are highly disparate in terms of income, geographic proximity, and regional zones of influence, they have two commonalities: (i) large numbers of districts that offer access to ready supplies of energy via oil, natural gas, or hydropower potential; [11] and (ii) strategic positioning to Beijing’s envisioned overland or maritime transit routes. In keeping with this strategy, most of the PRC’s financial diplomacy at the subnational level in these countries has been focused on the energy and transportation sectors.

Although India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka all attracted sizable financial diplomacy, Beijing focused its subnational strategy on cultural and exchange to nudge foreign publics to view the PRC more favorably. Like the previous group, India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka are strategically positioned for Beijing’s envisioned overland or maritime transit routes. However, they have fewer districts that offer ready access to oil and natural gas deposits (only 23 districts as compared to 72 districts in the previous six countries). Moreover, China may have recognized its need to rely more heavily on soft power in India, to refurbish its image with the public in the context of a geostrategic rivalry characterized by mutual suspicion, and in Sri Lanka, following the fallout from Beijing’s controversial bankrolling of Hambantota port and related investments (Thompson, 2001; Thompson & Dreyer, 2011; Custer et al., 2019a).

Beijing’s historical engagement with Afghanistan was notable primarily for its relative absence. During the period in question, Afghanistan received minimal amounts of any of the three public diplomacy tools we examined in this analysis. Beijing oriented this minimal viable level of public diplomacy activity almost exclusively to Kabul, the capital city. We term this minimal subnational presence an avoidance strategy.

There are four likely reasons for this approach. First, the level of physical insecurity outside of the capital may have made fostering ties with Afghan citizens or local leaders practically infeasible, hence the near exclusive focus on Kabul. Second, it could be that PRC leaders viewed the sizable presence of the US and coalition allies in Afghanistan at the time as diminishing its influence prospects, such that it focused attention on other geographic localities where it would meet with less resistance. Third, Beijing may have had bounded priorities regarding Afghanistan, primarily guarding against spillovers of instability—the “three evils” of religious extremism, terrorism, ethnic separatism—into China’s restive Xinjiang-Uyghur Autonomous region, which shares a 57-mile border with Afghanistan along the Wakhan Corridor (Scobel, 2021; Chen, 2015). Fourth, the Afghan government may not have put forward requests for Beijing’s assistance outside of the capital city, as they relied more heavily on other partners.

However, the critical question now is whether the US withdrawal of its military presence in Afghanistan in the summer of 2021, the collapse of the country’s pro-Western government, and the ascendance of the Taliban will provoke a reset in the PRC’s strategic calculus and how that might impact its engagement moving forward. In some respects, the US withdrawal has reset the board, in that there is one less impediment to the PRC changing its public diplomacy tactics and seeking to exert greater influence at the subnational level. Nevertheless, this is not fait accompli. The PRC’s priority continues to be containing instability (Huanxin, 2021), not launching a major economic or cultural charm offensive across the country. Moreover, as Scobell (2021) notes, “China is not the sole nor even the most obvious alternative to the US,” with other regional players such as Pakistan and Iran likely to have the inside influence track.

Now that we have established that Beijing indeed varies how it deploys public diplomacy tools at the national level, we turn in section 2.2 to the question of which communities are most likely to attract financing, why, and what this says about how the geographic reach of the PRC’s financial diplomacy with foreign publics.

2.2 Investment hotspots: Beijing’s financial diplomacy within countries

How wide or narrow of a financial diplomacy footprint does Beijing have within South and Central Asian countries? To what extent is exposure to Beijing’s financing restricted to a few large population centers versus visible across the country? To answer these questions, we pinpointed the geographic locations of Beijing’s financial diplomacy projects, compared to non-financial tools of cultural and exchange diplomacy, down to the first- and second-order administrative levels (most often provinces, states, and districts) within countries.

Analyzing the geographic spread of financial diplomacy dollars, a relatively small subset of communities captures the lion’s share of Beijing’s attention. We identified PRC financial diplomacy projects in 85 provinces and 137 (out of 2097) districts across the region between 2000 and 2017. [12] If the PRC distributed its money equally across these 85 provinces and 137 districts, the average assistance package would be worth approximately US$1.5 million per province and US$929 million per district. But is this equitable distribution how Beijing directs its assistance?

Finding #2. Beijing’s financial diplomacy is highly concentrated: it focuses the lion’s share of its state-directed financing to just 25 provinces (62 percent of financing) and 25 districts (41 percent of financing).

It turns out that Beijing has a deep but narrow financial diplomacy footprint, concentrating outsized investments in a small number of strategically important communities. In fact, the PRC targeted 62 percent (US$78 billion) of its financial diplomacy dollars to 25 provinces. The largest province-level recipient was Sindh province in Pakistan which Beijing bankrolled to the tune of nearly US$13 billion, approximately 10 percent of its financial diplomacy for all of South and Central Asia. Other big ticket investment locations included Turkmenistan’s Mary province (US$8 billion) and Pakistan’s Punjab province (US$7 billion).

If budgets are reflective of one’s real priorities, then it is notable that each of these three provinces attracted more money from Beijing between 2000-2017 than seven of the 13 countries in the South and Central Asia region. Taking a more granular view, a privileged club of 25 district-level recipients accounted for 41 percent (US$52 billion) of the PRC’s overall assistance across the entire region (Figure 2). Pakistan’s Karachi division alone pocketed US$8 billion of Beijing’s financial diplomacy, with Kazakhstan’s Atyrau district (US$5 billion) not far behind. Once again, these strategically important communities appear to be a much higher priority in the eyes of PRC leaders than some countries in the region. Of course, it is important to note that the communities which received Beijing’s assistance were likely also guided by the priorities of national leaders.

Notes: This map visualizes total financial diplomacy to districts in SCA countries from 2000 to 2017. Each circle represents a district that received a commitment related to financial diplomacy from China during this period. Financial figures are in constant USD 2017.

Source: AidData (2021).

Finding #3. More populous districts and those with natural gas pipelines are the most likely recipients of Chinese financial diplomacy dollars.

Some communities are clearly more attractive hotspots of investment for Beijing. This raises a critical question: why do some districts attract more of Beijing’s financial diplomacy dollars than others? There is, of course, the possibility that national or municipal leaders may have varying degrees of risk tolerance for accepting PRC assistance, creating an opt-in or opt-out dynamic, over which Beijing would have limited control. At the same time, this self-selection bias does not fully explain the sizable difference between districts that attract billions versus those that attract only millions or even hundreds of thousands of financial diplomacy dollars from Beijing.

Constructing a series of statistical models, we tested three possible hypotheses regarding variations in Beijing’s subnational financial diplomacy: (i) geostrategic importance, (ii) economic importance, and (iii) political importance. Table 2 below summarizes our hypotheses for why these factors might influence Beijing’s financial diplomacy allocations within countries, along with the proxy measures used for testing. The technical appendix offers an extensive discussion of the bivariate and multivariate regression models used to assess the statistical significance of relationships between Beijing’s financial diplomacy inputs and the attributes of potential recipient districts, along with the underlying source data for each of the variables tested. We briefly outline the conceptual rationale for each hypothesis below, as well as the results.

Some communities may hold more geostrategic importance, as they offer access to ready supplies of oil and natural gas, a priority for PRC leadership (Scobell et al., 2014) since China surpassed the US as the largest energy consumer in 2009 (Enerdata, 2021) and has become the world’s top energy importer (Hillman and Sacks, 2021). In light of Beijing’s plausible interests in influencing border disputes, we also considered proximity to a border with another country as another element of geostrategic importance.

In line with Beijing’s long-standing “going global” strategy (Wang, 2016; Dollar, 2015), large population centers may hold greater economic importance for PRC leaders because they represent lucrative markets for Chinese goods, services, and investment capital. This market attractiveness could be important for two reasons. Such markets can absorb excess Chinese manufacturing and construction capacity that is not fully utilized in the face of low consumption at home and instead deploy this productively abroad (Wuthnow, 2019; Custer and Tierney, 2019). They also allow PRC leaders to demonstrate that overseas assistance generates tangible benefits for Chinese citizens (i.e., jobs, revenues) to subdue growing criticism that this money should be spent at home (Hornby and Hancock, 2018). [13]

There is also good reason to believe that locations may vary in their attractiveness based on their political importance as capital cities or as the home regions of the political leaders Beijing hopes to influence to advance broader national interests—from security concessions to securing support for preferred foreign policy positions. Dreher et al. (2016) found that Chinese overseas development projects were disproportionately located in the home regions of presidents and prime ministers. Interviews conducted by Custer et al. (2019a) in Sri Lanka and Nepal give further credence to the idea that Beijing positions itself to help political leaders with their home constituencies, as it sited high-visibility public works projects (e.g., a cricket stadium, airport, highway, port) in the hometown of Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa and PRC officials reportedly accompanied Nepali leaders on campaign visits to their home regions.

|

Factor |

Hypothesis |

Proxy measures used |

|

Geostrategic importance |

Districts which provide ready access to oil and natural gas to satiate China’s energy needs or are proximate to international borders receive more of Beijing’s financial diplomacy |

Presence of oil and natural gas pipelines (Energy Web Atlas); presence of petroleum deposits (Lujala et al., 2007) |

|

Economic importance |

Districts which are lucrative markets to absorb Chinese goods, services, and capital receive more of Beijing’s financial diplomacy |

Economic output using nighttime lights (Li et al., 2020); district population (Tatem, 2017) |

|

Political importance |

Districts which capture the attention of political elites receive more of Beijing’s financial diplomacy to use as leverage |

District contains the birthplace of the country’s leader; presence of the capital city in a district |

Notes: For more information on the underlying source data for the proxy measures, see the accompanying technical appendix.

Putting these hypotheses to an empirical test allows us to move beyond theories and anecdotal examples to better understand why some communities attract more attention than others. We find that subnational communities that contain large population centers (economic importance) and those with operational natural gas pipelines (geostrategic importance) were more likely than their peers to receive financial diplomacy dollars from Beijing. [14] This finding suggests that Beijing believes the greatest return for its investments in financial diplomacy can come from gaining support in high population areas and from securing access to natural gas.

It is important to acknowledge that the siting of these investments does not solely come from Beijing’s interests, but also the priorities of SCA governments on the receiving end of these overtures. Nevertheless, the PRC ultimately determines what to bankroll and this, in and of itself, offers an important insight into its revealed priorities. Contrary to our expectations, measures of political importance (birthplace of a leader, capital city) did not appear to play as clear cut of a role in explaining which communities received PRC financial diplomacy. However, as we examine in Chapter 3, these factors appear to be more consequential in Beijing’s deployment of cultural and exchange diplomacy.

Reinforcing our observation in section 2.1, Beijing varies its approach between “extract,” “nudge,” and “avoid” countries when it comes to the relative importance of petroleum deposits (oil or natural gas) in communities that received financial diplomacy investments. In the club of six “extract” countries, communities that have petroleum deposits are more likely to attract Beijing’s financial diplomacy dollars. This relationship is most clear in Kazakhstan, but also extends to Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, and Nepal. India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, where Beijing employs a “nudge” strategy (i.e., more heavily weighted at the local level to cultural and exchange diplomacy rather than financing), have more ambiguous results, ranging from negative to weakly positive associations between the presence of petroleum deposits and communities that received financial diplomacy.

However, there is one case when using this paradigm to explain Beijing’s financial diplomacy breaks down. PRC leaders were more likely to bankroll financial diplomacy investments in Pakistani communities that generated lower (rather than higher) economic output once population and petroleum deposits were taken into account. This is distinct from Beijing’s approach in other countries, where there was a positive relationship between a community’s economic output and its reception of PRC financial diplomacy investments.

In section 2.3, we examine the dynamics of this case more closely and its implications in an era of great power competition between China, India, the US, and Russia, with access to strategic shipping corridors and oil and gas pipelines at stake.

2.3 Financial diplomacy in an era of great power competition

Although states employ rhetoric liberally to articulate their goals, budgets are arguably a more reliable metric of what they ultimately prioritize. Pakistan stands out among the SCA countries as attracting a disproportionate amount of Beijing’s public diplomacy overtures. The largest recipient of PRC financing by a significant margin, it also receives substantial amounts of cultural and exchange diplomacy, which we discuss in Chapter 3. Yet, as we have seen throughout this chapter, Beijing’s financial diplomacy footprint is narrow but deep in Pakistan.

Of Pakistan’s 37 second-level divisions—spanning four provinces, two autonomous territories, and the capital territory—Beijing directly channeled its financial diplomacy dollars into 20 districts over a nearly two-decade period. [15] However, Beijing’s volume of financial diplomacy dollars (from thousands to billions) and per capita spending (from US$0.02 to US$892 per person) varies substantially across these districts, which suggests further tiering of priorities, though some investments may also generate broader spillover benefits. In this section, we examine what may be animating Beijing’s interest in these subnational communities and how this gives insight into broader dynamics of contested influence in an era of great power competition.

Finding #4. Pakistan’s shipping corridors and pipelines attract nearly one-third of all of the PRC’s financial diplomacy across SCA countries, fostering economic ties with local, national, and regional implications.

The connective tissue behind Beijing’s financial diplomacy investments in Pakistan has been the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which accounts for the vast majority of PRC financing during the period. [16] Similar to other economic corridors, CPEC ticks the box for three common characteristics (Ali et al., 2021): (i) investments oriented around a relatively narrow geographical space surrounding key transportation infrastructure (i.e., roads, rails, canals); (ii) strategic bilateral initiatives aimed at connecting critical transit nodes across international borders; and (iii) a focus on physical infrastructure development to achieve broader goals.

With CPEC, the PRC aims to connect the existing Karachi deep-water port and the low-capacity Gwadar port (which Beijing hopes to convert into a deep-water port) in southwest Pakistan to the Kashgar dry port in southwestern Xinjiang (Ali et al., 2021; Hussain, 2021). Although port development is a central feature, CPEC serves as a much broader umbrella for a series of energy projects (pipelines and power plants), connective physical and digital infrastructure (roads, rails, fiber optic cables), and special economic zones. Theoretically, CPEC allows Beijing to achieve multiple economic, security, and geopolitical objectives simultaneously.

Economically, CPEC provides China with a direct line to the Indian Ocean (Kardon, 2020), and its emphasis on physical and digital connectivity could open new markets for Chinese goods, services, and capital not only in Pakistan, but also along the larger maritime silk road. Beijing views regional integration as placing its less-developed interior regions, such as Xinjiang and Tibet, on a better economic growth trajectory to catch up with the dynamism of its coastal cities (Ali et al., 2021). This connectivity could also improve the speed of shipping—“once fully functional, CPEC could transport a barrel of oil from the Middle East to China in 10 days, as compared to 35-45 days at present” (ibid). [17] Less certain is whether this reduces costs: transporting oil from Gwadar to Xinjiang is roughly $15 per barrel, substantially higher than the estimated $2 per barrel cost of shipping via the Malacca Strait (Kardon, 2020).

There are domestic security dimensions to Beijing’s interests in CPEC that may make up for the extra $13 shipping cost per barrel. PRC leaders view preserving stability at home as paramount and the three evils—separatism, terrorism, extremism—as direct threats to the durability of Chinese Communist Party rule. Nowhere is this dynamic seen as acutely as in the PRC’s restive western Xinjiang-Uyghur Autonomous Region, where Beijing hopes that the promise of economic development may be enough to curb the appeal of Uyghur separatist movements and quell domestic terrorism (Baruah, 2018).

Inequities in development prospects, along with the CCP’s heavy-handed surveillance and infringements on basic human rights, have inflamed tensions between the Uyghur minority and Han majority (Hussain, 2021). Like the discussion of Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor, Beijing is also concerned about potential spillovers from insecurity in Pakistan inflaming unrest in Xinjiang—either from Uyghur communities that have settled just across the border in Gilgit-Baltistan or from persistent insurgent movements in Balochistan farther south (ibid).

Energy security, including domestic and international considerations, is another animating factor fueling Beijing’s interest in CPEC. China imports over 10,000 barrels of oil a day, the vast majority of which transit through the straits of Malacca. PRC leaders have expressed concern that the busy sea lane could become a maritime choke point, threatening China’s ability to reliably access 80 percent of its crude oil supplies, in the event of hostilities with the US and India (Hillman and Sacks, 2021; Hussain, 2021).

This “Malacca Dilemma” has incentivized Beijing to diversify both its energy suppliers and transport routes (Hillman and Sacks, 2021; Hussain, 2021), hence the interest in the trifecta in Pakistan’s petroleum deposits (oil or natural gas) and energy capacity, pipelines to transport energy supplies, and proximity to strategic shipping lanes (e.g., Red Sea, Strait of Hormuz, Persian Gulf) to facilitate imports from farther afield. Even if these supplies may come at a higher financial cost, this diversification strategy provides the PRC with greater autonomy of operation away from active monitoring by strategic competitors, such as the US and India, and reduces the PRC’s perceived energy insecurity (Wuthnow, 2017; Hussain, 2021).

Moreover, beyond energy security, Beijing has other geopolitical interests in leveraging CPEC to project power and influence, both within Pakistan and across the South and Central Asia region. As Hussain (2019) rightly notes, “China-Pakistan bilateral relations are decades old and have achieved a factor of durability.” Pakistani leaders have consistently demonstrated support for their PRC counterparts at critical junctures—from being the “first Muslim and third non-Communist country to recognize the PRC in 1951” (Ali et al., 2021) to backing Beijing in the United Nations and refraining from criticism over its treatment of the Uyghur Muslim minority (Hillman and Sacks, 2021). However, the arrival of CPEC has ushered in a new era in the relationship between the two countries—shifting from one characterized by close political ties among a small cadre of officials and bureaucrats to much broader economic integration and interdependence, with implications at local, national, and regional levels.

Beijing also wants to leverage a deeper relationship with Pakistan and the strategic positioning of CPEC for broader signaling and force projection within the region. One of the PRC’s rationales in investing in Gwadar is as a dual-use deep-water port that can accommodate People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) ships and provide logistics and operations support to project military power in the Indian Ocean as part of its broader “string of pearls” strategy (Kanwall, 2018; Hillman and Sacks, 2021; Ali et al., 2021).

Some view CPEC as a “game changer” and an example of “win-win cooperation” to boost Pakistan’s economy and energy supply (Hussain, 2019). Yet, controversies have arisen over debt sustainability and corruption (Hillman and Sacks, 2021). Eighty percent of PRC financial diplomacy to Pakistan is in the form of less concessional lending which approaches market rates or equity (Custer et al., 2019a). In practice, this means that countries like Pakistan are increasingly in jeopardy of borrowing at rates they cannot easily repay and against unfavorable return on equity terms, [18] both of which increase the PRC’s political leverage. Moreover, Malik et al., (2021) identified Pakistan as among the top BRI countries worldwide where Chinese-bankrolled infrastructure projects were associated with scandals, controversies, or alleged violations (10 projects), community or ecosystem harm (1 project), and claims of corruption or financial wrongdoing (4 projects).

There were also heated debates within Pakistan about which communities were (and were not) to be incorporated into the route between Gwadar and Kashgar (Hussain, 2019). Pashtun opposition political parties reportedly accused then-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and his younger brother Shahbaz Sharif, Chief Minister of Punjab, of rerouting CPEC to disproportionately benefit communities in the Punjab division at the expense of Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, as well as syphoning funds into political campaigns (ibid). Balochistan, the home province for the Gwadar and Karachi ports in the south and Gilgit-Baltistan to the north, seen as “the gateway of CPEC,” continues to be plagued by persistent physical insecurity from separatist movements and terrorist groups such as Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (Ali et al., 2021).

Internationally, CPEC has spurred a great energy race in South and Central Asia, with Pakistan as an important lynchpin in many competing plans. Russia signed a July 2021 agreement with Pakistan to build an 1100-kilometer natural gas pipeline, the PakStream Gas Pipeline (PSGP) project, from Port Qasim in Karachi to Lahore by the end of 2023 (Business Standard, 2021). [19] India condemned CPEC’s incorporation of Gilgit-Baltistan, which brackets the disputed Jammu and Kashmir region (Hussain, 2019). But New Delhi seeks to access Turkmenistan’s Galkynysh gas field via a Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline (Hydrocarbons Technology, 2021). [20] India has considered a possible Iran-Pakistan-India (IPI) pipeline, but US efforts to sanction Iran have prevented the project from being completed. US interests in TAPI are a direct counter to the PRC’s CPEC, which it joined India in condemning in October 2017 (Ali et al., 2021). US-Russia competition over natural gas is more focused in the Caucasus than Pakistan (Abbhi, 2016; Bryza, 2020; Johnston, 2019). [21]

In this chapter, we found that Beijing does not have a one-size fits all approach, but rather employs three distinct public diplomacy strategies—"extract,” “nudge,” and “avoid”—at the local level to advance economic, security, and geopolitical goals in SCA countries. We then identified that the PRC’s financial diplomacy footprint within countries is narrow but quite deep, with the potential for outsized influence in a small subset of communities, particularly more populous districts, as well as those with natural gas pipelines and petroleum deposits (oil or natural gas). However, a deep dive into Pakistan’s CPEC underscored the importance of examining the interplay of macro-level objectives with micro-level community attributes in understanding how Beijing deploys its financial diplomacy to foster economic ties and advance its national interests.

In Chapter 3, we turn from financial diplomacy to take a closer look at a series of soft power tools in Beijing’s public diplomacy toolkit. We examine each tool in isolation and then seek to understand whether and how Beijing employs them synergistically to influence foreign leaders and publics in line with its interests. We will also consider how Beijing’s efforts to cultivate economic and human ties interact.

Chapter 3 Social ties: How does Beijing leverage education, culture, and exchange to amplify its foreign influence strategy?

Key findings in this chapter:

-

Beijing’s education assistance projects have increasingly emphasized scholarships, technical assistance, and training as a pipeline to feed into its higher education institutions.

-

The PRC offers less burdensome requirements, numerous scholarships, English language curricula, and new training modalities to become a premier study abroad destination.

-

Russia, India, and the US have longer-standing presence, but the PRC now accounts for 30 percent of language and cultural institutions in the region, only surpassed by the US.

-

Beijing has cultivated 193 central-to-local or local-to-local ties with 174 cities across the SCA region, but over half of all ties (52 percent) were focused on just 16 priority cities.

As the PRC’s economy grows stronger, this could create the perception of an “income premium,” in that those who embrace Chinese language and norms may have far greater economic prospects than those who do not (Xie, 2019). In this respect, Beijing’s economic and soft power tools are arguably most formidable in exerting influence when they are employed in synergy. As SCA countries become economically integrated and connected with the PRC (the focus of Chapter 2), the more open they become to embracing Chinese language, culture, and norms (the focus of this chapter). Relatedly, the more that SCA publics and elites build closer people-to-people ties with counterparts in China, it is more likely that they turn to these social networks when it comes to sourcing goods, services, capital, and other economic partnerships.

In the remainder of this chapter, we examine how Beijing has used educational cooperation and student exchange (section 3.1) and language and culture promotion (section 3.2) to cultivate social or people-to-people ties and advance its national interests across SCA countries. In section 3.3, we explore how wide and deep Beijing’s social ties appear to be within countries and possible explanations for why some communities have attracted more attention than others.

3.1 Education as soft power: Beijing’s educational assistance and student exchange efforts

Education is a powerful lever to socialize foreign publics to “want what you want” (Nye, 2011). Economically, the PRC positions itself as a premier study abroad destination, not only to generate valuable tuition revenues from foreign students, but also to cultivate markets for Chinese goods, services, and capital. Geopolitically, educational cooperation is a brand-builder for PRC leaders to win admiration for Chinese values, culture, and civilization after a “century of humiliation” (Tischler, 2020). Education also enhances security interests. Internationally, Beijing can socialize foreign publics to its ideas and norms, curb criticism, and increase the CCP’s legitimacy. Domestically, some scholars have argued that the PRC can recast restive western regions as international education hubs to promote internal stability (Welch, 2018; Li, 2018; Yalun, 2019).

In this section, we focus the conversation on two areas central to Beijing’s influence strategy in the South and Central Asia region. In section 3.1.1 we examine the PRC’s state-directed educational assistance to SCA countries in the form of financing or in-kind support. In section 3.1.2 we take a closer look at the PRC’s efforts to facilitate study abroad programs and vocational training opportunities for SCA students.

3.1.1 Educational assistance to SCA countries

The PRC bankrolled an estimated 251 educational assistance projects for 12 SCA countries between 2000-2017. This included an estimated US$6.6 billion in financing and substantial in-kind provision of labor, materials, technical assistance, and equipment. [22] The 2008 international financial crisis and the 2013 announcement of the BRI were important inflection points. There was a consistent uptick in the overall volume of educational assistance projects across three time periods: 2000-2008 (61 projects), 2009-2013 (82 projects), and 2014-2017 (108 projects). Moreover, Beijing’s priority countries (Figure 3) and preferred modality shifted across the three periods.

Kazakhstan was by far the largest recipient of educational assistance projects (18 percent) and dollars (62 percent) early on, but by the end received negligible assistance (Table 3). In the 2009-2013 period, Nepal received the most projects (24 percent), but Pakistan and Bangladesh pocketed most of the financing (31 percent and 25 percent, respectively). In the post-BRI period, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan all received large numbers of educational assistance projects. Nevertheless, Pakistan and Bangladesh together attracted three-quarters of Beijing’s financial outlay after 2014. We do not see any indication that this educational assistance corresponds to the presence or absence of a Confucius Institute or Confucius Classroom.

Finding #5. Beijing’s education assistance projects have increasingly emphasized scholarships, technical assistance, and training as a pipeline to feed into its higher education institutions.

The substantive focus of Beijing’s educational assistance can be clustered into four groups. First, 46 percent of projects were focused on constructing buildings or donating equipment (e.g., books, computers, furniture). Nepal and Uzbekistan were the two countries most likely to receive such projects. [23] Second, scholarships, vocational training, and technical assistance accounted for 39 percent of projects. [24] Bangladesh and Afghanistan were most likely to receive this type of assistance. Third, joint research and knowledge production projects, including the formation of study centers, Confucius Institutes and Classrooms, think tanks, and academic collaborations accounted for 11 percent of projects. [25] Finally, the remaining 11 projects classified were more varied, but still included an element of fostering culture or education, such as supporting sewing circles in Tajikistan or paying teacher salaries at a school for autism in the Maldives. Early on, Beijing’s assistance was evenly distributed across all four categories (Table 4). Building construction and equipment donations became the major emphasis in the 2009-2013 period. After the launch of the BRI, Beijing has placed more attention on scholarships, technical assistance, and vocational training, in line with a stronger emphasis on shaping norms and media narratives. In section 3.1.2, we examine how Beijing has parlayed this educational cooperation with SCA countries into creating a pipeline of students to feed into its higher education institutions, as well as experimenting with new modalities to deliver vocational training and distance education in SCA countries.

Source: AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 2.0.

|

2000-2008 |

2009-2013 |

2014-2017 |

All years |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Afghanistan |

9 |

8 |

16 |

33 |

|

Bangladesh |

9 |

10 |

11 |

30 |

|

India |

1 |

3 |

4 |

8 |

|

Kazakhstan |

11 |

5 |

2 |

18 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

3 |

3 |

6 |

12 |

|

Maldives |

2 |

1 |

8 |

11 |

|

Nepal |

3 |

20 |

10 |

33 |

|

Pakistan |

9 |

9 |

17 |

35 |

|

Sri Lanka |

3 |

12 |

7 |

22 |

|

Tajikistan |

3 |

7 |

13 |

23 |

|

Turkmenistan |

3 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

|

Uzbekistan |

5 |

3 |

14 |

22 |

|

Total |

61 |

82 |

108 |

251 |

Notes: Count of total PRC educational assistance projects to SCA countries, grouped into three time periods. Source: AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 2.0.

|

2000-2008 |

2009-2013 |

2014-2017 |

All years |

|

|

Buildings and equipment |

25 |

51 |

40 |

116 |

|

Scholarships, vocational training, and technical assistance |

23 |

23 |

51 |

97 |

|

Total |

61 |

82 |

108 |

251 |

|---|

Notes: This table shows counts of PRC educational assistance projects in SCA countries by category, grouped into three time periods.

Source: AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 2.0.

3.1.2 Higher education exchange with SCA countries

Beijing has funneled substantial money into helping China’s top-tier higher education institutions (HEIs) improve facilities, internationalize curriculums, host foreign students and faculty, and broker cooperative agreements with counterpart institutions abroad. Buoyed by these state investments, Chinese HEIs have increasingly earned top spots on international academic rankings (Welch, 2018). In parallel, PRC leaders have pursued a proactive external-facing strategy to woo international students with a potent mix of “scholarships, loosened visa requirements, and cooperative agreements” (Custer et al., 2018 and 2019b). As a result, China has joined the ranks of the most popular study abroad destinations, attracting nearly 500,000 foreign students from 196 countries in 2018 to study in over 1,000 HEIs across 31 provinces and autonomous regions (China MoE, 2019).

Although its ambitions are global, the PRC has particular interest in stoking demand among SCA students to study in China. Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, the PRC had made substantial progress towards this goal (Figure 4), growing the number of SCA students studying in China from 33,211 in 2010 to 92,273 in 2017—a 178 percent change within eight years (Custer et al., 2019a). [26] However, the runaway growth in foreign students studying in China appeared to be slowing down, even prior to COVID-19 (Hartley, 2019). [27] As the PRC refused to reinstate visas (Yan, 2021), SCA students became “stranded,” unable to resume or begin their studies. To navigate this new normal, the PRC is experimenting with online learning platforms (Yao et al., 2020) and has doubled down on Luban Workshops, which pair Chinese HEIs and firms with host organizations in other countries, to deliver vocational training within SCA countries.

In the remainder of this section, we take a closer look at three strategies Beijing has historically employed to compete with traditional study abroad destinations: (i) loosening visa restrictions; (ii) offering state-backed scholarships; and (iii) reducing language, technical, and geographic barriers through expanding English-language offerings, exporting vocational training via Luban Workshops, and promoting Mandarin abroad.

Source: CSIS China Power and China Foreign Affairs Yearbook.

Finding #6. The PRC offers less burdensome requirements, numerous scholarships, English language curricula, and new training modalities to become a premier study abroad destination.

In pre-pandemic times, Beijing sought to reduce transaction costs for SCA students to study abroad in China, in line with its BRI Education Action Plan (China MoE, 2016). [28] Visa requirements—which in many preferred destination countries include visa issuance fees, health requirements, and proof of the student’s ability to cover their personal financial expenses—can introduce cost- and time-intensive hurdles for foreign students that must be overcome to study abroad. PRC leaders, seeking to remove friction and facilitate “smooth channels for educational cooperation” (China MoE, 2016) promoted several strategies to ease restrictions for SCA students to study in China. Putting this commitment to the test, we assess just how easy it is for SCA students to study in China, versus other destinations such as Russia, the US, and the UK.

The PRC offers the least burdensome visa requirements—in terms of cost, health requirements, and proof of payment—for students from most countries in the SCA region, assuming it reinstates its previous policy once COVID-19 concerns abate (Figure 5). Russia comes close to the PRC in terms of ease of visa acquisition, but only in a limited number of countries. Moscow employs relatively lax visa requirements for students from Commonwealth of Independent States’ countries (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan), though it imposes higher costs and health requirements for other South and Central Asian countries.

For applicants from most SCA countries, the PRC charges US$50 or less for a student visa [29] and caps the proof of payment requirement to US$2,500 per year of study. [30] Comparatively, to study in London the average SCA student would need to pay nine-times more for a UK student visa (US$470) and demonstrate capacity to cover US$21,475 or £16,008 in living expenses per year (US$1,790 or £1,334 per month). The US, albeit cheaper than the UK, still charges SCA students three times as much for a standard US student visa (US$160). Russia’s fees are lower than the English-speaking countries, but still cost prospective students $75 to $128.

These differences in visa regulations alone are striking confirmation of the PRC’s intent to compete to become the preferred study abroad destination today and cement relationships with the SCA region’s future public, private, and civil society leaders. Nevertheless, the PRC’s approach to SCA countries is not monolithic and it varies its visa regulations across the region. Examining these differences is instructive in illuminating Beijing’s revealed priorities, as the PRC’s requirements vary between countries to a much greater degree than its study abroad competitors. [31] This is best exemplified by comparing divergent requirements (see Figure 5) for three early signatories which joined the BRI in 2013: Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Kyrgyzstan.