Civic Space Profile

Republika Srpska

Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence

Emily Dumont and Lincoln Zaleski

April 2023

Executive Summary

As a companion to AidData’s main Bosnia and Herzegovina Country Report, this supplemental profile surfaces insights about the health of civic space and vulnerability to malign foreign influence specific to the Republika Srpska. The analysis was part of a broader three-year initiative by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to produce quantifiable indicators to monitor civic space resilience in the face of Kremlin influence operations over time and across 17 countries of Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E), including 7 territories that are occupied or autonomous and vulnerable to malign actors.

Below we summarize the top-line findings from our indicators on the channels of Russian malign influence operations, as well as the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Republika Srpska:

- Russian-backed Civic Space Projects: The Kremlin supported 1 civic space regulator in Republika Srpska via 2 relevant projects between January 2015 and September 2020 which emphasized training local law enforcement units. Russian state overtures were oriented towards Banja Luka, the capital of Republika Srpska. The Kremlin exclusively supported the Republika Srpska Ministry of the Interior.

- Russian State-run Media: Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News referenced civic space actors in Republika Srpska 33 times from January 2015 to March 2021; however the lion’s share of mentions were focused on Western or Russian civil society actors operating in Republika Srpska. Media organizations were the most frequently mentioned domestic organizations, followed by political parties. The overall tone of mentions was largely neutral, though Russian state media often attributed negative coverage to opposition protesters.

- Restrictions of Civic Actors: Civic space actors in Republika Srpska were the targets of 36 restrictions between January 2015 and September 2020. Eighty-six percent of these restrictions involved harassment or violence, followed by newly proposed or implemented restrictive legislation (11 percent), and legal action brought by local authorities (3 percent). Journalists and other members of the media were the targets in over half (58 percent) of the instances of violence and harassment, whereas formal CSOs and NGOs were more often targeted through restrictive legislation (50 percent of instances). The preponderance of harassment or violence was initiated by the Government of Republika Srpska (68 percent), habitually through the police, but also by politicians and bureaucrats who often engaged in verbal attacks and threats.

A Note on Vocabulary

The authors recognize the challenge of writing about contexts with ongoing hot and/or frozen conflicts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consistently label groups of people and places for the sake of data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that terminology is political, but our use of terms should not be construed to mean support for one faction over another. For example, when we talk about Republika Srpska, we do so recognizing that there are local authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the Bosnian government in Sarajevo. Or when we analyze the local authorities’ legislation or legal action to restrict civic action, it is not to grant legitimacy to the laws or courts of separatists, but rather to glean meaningful insights about the ways in which institutions are co-opted or employed to constrain civic freedoms.

Acknowledgements

This supplemental profile was prepared by Emily Dumont and Lincoln Zaleski. John Custer, Sariah Harmer, Parker Kim, and Sarina Patterson contributed editing, formatting, and supporting visuals. We acknowledge the assistance of Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Kelsey Marshall, and our research assistants for their invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report: Jacob Barth, Kevin Bloodworth, Callie Booth, Catherine Brady, Temujin Bullock, Lucy Clement, Jeffrey Crittenden, Emma Freiling, Cassidy Grayson, Annabelle Guberman, Sariah Harmer, Hayley Hubbard, Hanna Kendrick, Kate Kliment, Deborah Kornblut, Aleksander Kuzmenchuk, Amelia Larson, Mallory Milestone, Alyssa Nekritz, Megan O’Connor, Tarra Olfat, Olivia Olson, Caroline Prout, Hannah Ray, Georgiana Reece, Patrick Schroeder, Samuel Specht, Andrew Tanner, Brianna Vetter, Kathryn Webb, Katrine Westgaard, Emma Williams, and Rachel Zaslavsk. The findings and conclusions of this supplement are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

This research was made possible with funding from USAID's Europe & Eurasia (E&E) Bureau via a USAID/DDI/ITR Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) cooperative agreement (AID-A-12-00096). The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

Citation

Dumont, E., Zaleski, L. (2023). Republika Srpska: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence. Supplemental Profile. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary.

1. Introduction

The Russian government supports occupied or autonomous territories as a tactic to weaken perceived adversaries and further its influence in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. [55] The Kremlin appears to have two overarching goals for its overtures in Republika Srpska: block the influence of Western actors and bolster the legitimacy and autonomy of the Government of Republika Srpska.

As a companion to AidData’s main Bosnia and Herzegovina Country Report, this supplemental profile examines the Kremlin’s tools of influence in Republika Srpska’s civic space [56] which seek to manipulate local attitudes in support of two key narratives which advance its interests. First, the Kremlin attempts to discredit Western organizations in Republika Srpska, encouraging the harassment of foreign-funded civil society organizations (CSOs) and criticizing institutions like the Office of the High Representative (OHR) in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Second, the Kremlin bolsters the legitimacy and strength of Republika Srpska’s authorities, encouraging a crackdown on dissent through legislation and training programs for local law enforcement.

This profile is part of a broader three-year research effort conducted by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to collect and analyze vast amounts of historical data on civic space and Russian influence across 17 countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E), including 7 territories that are occupied or autonomous and vulnerable to malign actors. For the purpose of this project, we define civic space as: the formal laws, informal norms, and societal attitudes which enable individuals and organizations to assemble peacefully, express their views, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction.

In the remainder of this supplemental profile, we provide additional details on how the Russian government uses its state institutions to influence Republika Srpska’s population in support of these narratives. In section 2, we examine Russian projectized support relevant to civic space and analyze Russian state-backed media mentions of civic space actors. In section 3, we enumerate restrictions of civic space actors. A methodology document is available via aiddata.org.

Table 1. Quantifying External Influence on and Restrictions of Republika Srpska’s Civic Space

|

Civic Space Barometer |

Supporting Indicators |

|

Russian state financing and in-kind projectized support relevant to civic space actors or regulators (January 2015-September 2020) |

|

|

Russian state media mentions of civic space actors or democratic rhetoric (January 2015-March 2021) |

|

|

Restrictions of civic space actors (January 2017-September 2020) |

|

Notes: Table of indicators collected by AidData to assess the health of Republika Srpska’s domestic civic space and vulnerability to Russian influence. Indicators are categorized by barometer (i.e., dimension of interest) and specify the time period covered by the data in the subsequent analysis.

2. External Channels of Influence: Kremlin Civic Space Projects and Russian State-Run Media in Republika Srpska

In this project, we tracked financing and in-kind support from Kremlin-affiliated agencies to: (i) build the capacity of those that “regulate” the activities of civic space actors; and (ii) co-opt the activities of civil society actors within E&E countries in ways that seek to promote or legitimize Russian policies abroad. The Kremlin supported 1 civic space actor in Republika Srpska via 2 relevant projects during the period of January 2015 to September 2020. In this section, we unpack more specifics on the suppliers (section 2.1), recipients (section 2.2), and focus of Russian state-backed support to Republika Srpska’s civic space (section 2.3).

Since E&E countries are exposed to a high concentration of Russian state-run media, we analyzed how the Kremlin may use its coverage to influence public attitudes about civic space actors (formal organizations and informal groups), as well as public discourse pertaining to democratic norms or rivals in the eyes of citizens. Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced civic actors in Republika Srpska a total of 33 times from January 2015 to March 2021. The majority of these mentions (21 instances) were of foreign and intergovernmental actors operating in Republika Srpska, while the remaining portion (12 instances) consisted of mentions of domestic civic space actors. Russian state media covered a diverse set of civic actors, mentioning 15 organizations by name, as well as 8 informal groups operating in Republika Srpska’s civic space. In this section, we examine Russian state media coverage of domestic (section 2.4) and external (section 2.5) actors in Republika Srpska’s civic space, and how this has evolved over time (section 2.6).

2.1 The Suppliers of Russian State-Backed Support to Republika Srpska’s Civic Space

Moscow prefers to invest in relationships with government institutions of the Republika Srpska which regulate civic space to promote cooperation and joint training activities, which accounted for 100 percent of its overtures. However, the Russian government’s interest in cultivating these relationships does not appear to be consistent (Figure 1), as civic space-oriented funding to Republika Srpska’s institutions did not continue after 2016.

Figure 1. Russian Projects Supporting Civic Space Actors in Republika Srpska by Type

Number of Projects Recorded, January 2015 - September 2020

The Kremlin routed its engagement with civic space through only one channel: the Ministry of the Interior of Republika Srpska. While the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs usually finances law enforcement within the Russian Federation, the Ministry also conducts external outreach with partner countries. The majority of these activities focus on memorandums of understanding (MoUs), information sharing agreements, and training—sending Russian trainers to partner country offices, or sending local law enforcement to train with Russian units. Within the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Main Directorate for Moscow was the specific unit that spearheaded cooperation activities with the Republic of Srpska’s Ministry of the Interior. The Moscow directorate took the lead in facilitating personnel exchange between the Ministry of the Interior of Republika Srpska and the broader Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs in 2016.

Compared to other territories, Russia’s primary instruments of soft power are notably less present in Republika Srpska. There are no branches of Rossotrudnichestvo in the region, [57] and other key Russian state organizations, such as the Gorchakov Fund, [58] are absent as well. However, Russkiy Mir has established two Cabinets in Banja Luka and Modriča in Republika Srpska, as well as the Russian Center of the National and University Library of Republika Srpska in Banja Luka. These three Russkiy Mir centers promote Russian language and culture through classes and programs in Republika Srpska, creating in-roads for further Russian soft power influence.

Figure 2. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Civic Space Actors in Republika Srpska

Number of Projects, 2015-2020

|

Russian Org Involved |

Recipient Org Name |

Number of Projects |

|

Ministry of the Interior |

The Republic of Srpska Ministry of the Interior |

2 |

Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

2.2 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Republika Srpska’s Civic Space

The Republika Srpska’s Ministry of the Interior was the sole recipient of identified instances of Kremlin civic space-relevant support. This Banja Luka-based body oversees police, counterterrorism, public security, and property protection activities. The mandate for public security and property protection provides the justification for police units to constrain and repress demonstrations or public political actions, potentially curtailing one component of civic space. Police across the region often further constrain civic space through harassment and investigation of political opposition and community groups. These two tactics were both used by police throughout 2018 and 2019 to restrict the “Justice for David” protests in Banja Luka, whether by banning the group from gathering near certain buildings and dispersing protests, or by issuing warrants for the arrest of the protests’ leader, Davor Dragičević. [59]

Russian business actors also favor Republika Srpska over the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in foreign investment and energy projects. [60] Both sets of these overtures, governmental and business, have been linked by the Alliance for Securing Democracy to a broader Kremlin strategy of promoting separatism in Republika Srpska. [61] Given the focus of Russian support to institutional development in other territories, the support to Republika Srpska’s Ministry of the Interior appears to align with the Kremlin’s playbook of using its political investments to bolster ethnic nationalism and separatism.

Figure 3. Locations of Russian Support to Civic Space Actors in Republika Srpska

Number of Projects, 2015-2020

|

Recipient Organization Subnational Location |

Project Count |

|

Banja Luka |

2 |

|

Total |

2 |

2.3 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Republika Srpska’s Civic Space

Kremlin-backed support in Republika Srpska focused on providing assistance to a government agency focused on domestic security, building the capacity of local authorities to crack down on dissenters that ran counter to the Kremlin’s interests. It did so not through direct transfers of funding, but rather through other modes of non-financial support, such as training, technical assistance, and other in-kind contributions. In Republika Srpska, the two principal modes of engagement from Russian actors were memorandums of understanding (MoUs) and a commitment to implement joint trainings for members of the Republika Srpska Ministry of the Interior.

In their October 2015 MoU, Republika Srpska’s Ministry of the Interior and the Main Directorate of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs for Moscow cited the need for closer cooperation and contact to counter transnational crimes and serious criminal offenses. This document set the groundwork for joint training, support to further staff specialization, and mobility of staff between the two units.

In April 2016, Republika Srpska’s Ministry of the Interior and the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs built upon the October 2015 memorandum by bringing Russian instructors to train members of the Ministry and arranging for members of the Special Police Unit (Specijalna Antiteroristička Jedinica, or SAJ) to train in Russia. This elite unit of Republika Srpska’s police is responsible for counter-terrorism operations, detecting and neutralizing criminal groups, hostage situations, repressing rebellions, and establishing public order and peace in high risk situations. [62]

2.4 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Civic Space Actors in Republika Srpska

Roughly half (58 percent) of Russian media mentions pertaining to domestic actors in Republika Srpska’s civic space referred to specific groups by name. The 7 named domestic actors represent a diverse cross-section of organizational types, ranging from political parties to media outlets. Media organizations were the most frequently mentioned organization type (4 mentions), followed by political parties (3 mentions). The newspaper Glas Srpske (2 mentions) was the only domestic civic organization mentioned more than once.

Russian state media mentions of specific civic space actors in Republika Srpska was entirely neutral (100 percent) in tone. Compared to external actors, Russian state media did not mention domestic organizations at a high rate, choosing instead to focus on Bosnian and Russian civil society actors present in, or oriented towards, Republika Srpska.

Aside from these named organizations, TASS and Sputnik made 5 generalized mentions of 4 informal civic groups during the same period. Coverage of these organizations was predominantly neutral (60 percent) as well, with the remaining mentions consisting of 2 “somewhat negative” mentions (40 percent). Russian state media attributed both negative mentions to protesters in Republika Srpska. Coverage of most domestic groups was neutral; however, protesters dissenting against Republika Srpska’s government were met with somewhat negative coverage from Russian state media. While protesters (2 mentions) were not given significant coverage, when Russian state media mentioned these informal groups, 100% of these mentions were negative.

When considering the domestic civic actors in Republika Srpska as a whole, there are two trends surrounding their coverage by Russian state media. First, Russian state media did not provide significant coverage to domestic civic actors, focusing instead on foreign and intergovernmental organizations in Republika Srpska. Second, domestic dissent through protests and activism is rarely mentioned with regard to Republika Srpska, and when dissenting informal groups are mentioned, they are covered in a negative light. These trends are reflected in the top mentioned domestic organizations.

Aside from Glas Srpske and “protesters,” Russian state-owned media attributed only one neutral mention to all other domestic civic actors in Republika Srpska.

Figure 4. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in Republika Srpska by Sentiment

Number of Mentions, January 2015 to March 2021

2.5 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in the Civic Space of Republika Srpska

The majority of Russian state mentions of civic actors were related to external organizations operating within Republika Srpska. [63] TASS and Sputnik mentioned 3 intergovernmental organizations (7 mentions) and 6 foreign organizations (10 mentions) by name, as well as 4 general foreign actors (4 mentions). Intergovernmental organizations monitoring governance and security threats in Republika Srpska and foreign media outlets reporting in the region dominated the external mentions.

Russian state-owned media mentioned the Office of the High Representative (OHR) in Bosnia and Herzegovina most often when referencing the civic space of Republika Srpska (4 mentions). Russian media attributed predominantly negative sentiment to OHR, calling for its abolition and criticizing the institution for “humiliating” Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the same article, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov highlights Russia’s interests in Republika Srpska and denies any knowledge of “harmful influence” in the region. [64] This messaging highlights an interesting trend of Russian coverage of Republika Srpska, where Russian media rebuke international institutions like the OHR as directly harmful to its interests in the region.

Figure 5. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Republika Srpska by Sentiment

Number of Mentions, January 2015 - March 2021

Mentions of foreign and intergovernmental civic actors involved in Republika Srpska were overwhelmingly neutral (84 percent). The only non-neutral mentions were 2 “somewhat negative” and 1 “extremely negative” mention of the OHR, and 1 “somewhat positive” mention of the Immortal Regiment, a yearly march in commemoration of the Russian victory in World War II. In Republika Srpska, Russian state media is supportive of Russian cultural and historical organizations, like the Immortal Regiment, and critical of Western institutions, such as the OHR.

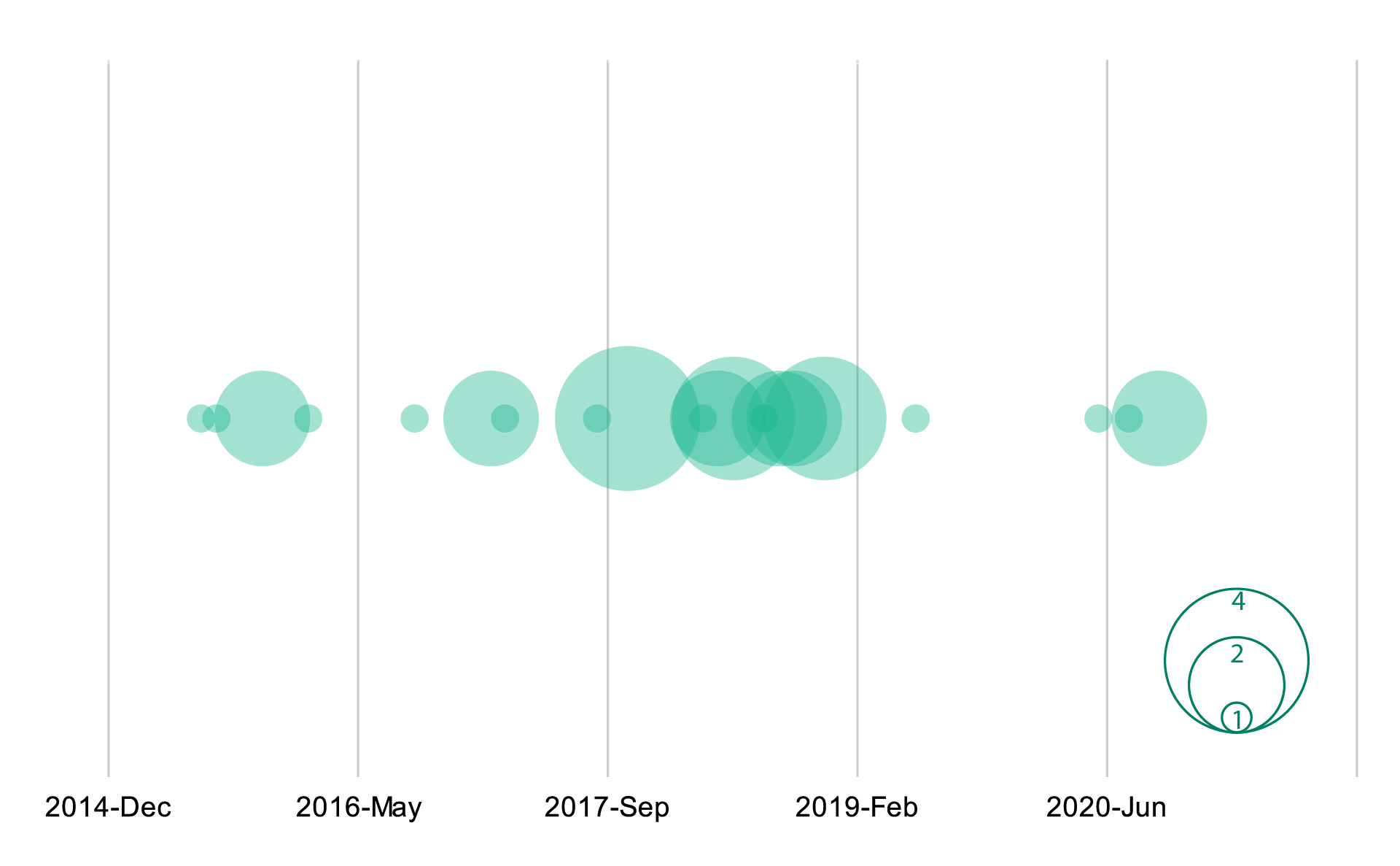

2.6 Russian State Media’s Focus on Republika Srpska’s Civic Space over Time

For other territories, Russian state media mentions spike around major events and tend to show up in clusters. However, this is not the case in Republika Srpska, as most key events are largely unreported by Russian state-owned media. The biggest spike occurred in November 2017 when the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) ruled that Bosnian Serb leader Ratko Mladic played a significant role in the Srebrenica Massacre (4 mentions). Events that received some coverage were Republika Srpska’s general election in October 2018 (2 mentions) and the “Justice for David'' protests in December 2018 (2 mentions).

Figure 6. Russian State Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors in Republika Srpska

Number of Mentions Recorded

As noted before, Russian state-owned media did not attribute much coverage to Republika Srpska from January 2015 to March 2021. The largest spike in mentions is in November 2017, after the ICTY ruling on Ratko Mladic. Russian state media adamantly defended Mladic, stating that “Among Bosnia's Serb community, in Serbia, Russia and elsewhere in Eastern Europe, officials, academics, and other observers have rejected the blunt and unequivocal placing of blame for the carnage during the Bosnian war on the Bosnian Serbs alone.” [65] Russian coverage of the event was highly critical, arguing that the ruling was “anti-Serb” and criticizing the West. [66]

Russian state media coverage of civic actors in Republika Srpska highlights some interesting takeaways. First, Russian state media coverage remained predominantly neutral, with the exception of protesters and Western institutions. Coverage of protesters was negative, with the Russian government seeming to support the Government of Republika Srpska against the protesters. Russian state media also criticized the OHR and the ICTY as being tools for Western influence in Republika Srpska. These trends suggest that the Kremlin uses its state-owned media influence in Republika Srpska to strengthen the local government and increase its local popularity amongst the Bosnian Serb population. Second, civic groups in Republika Srpska received relatively little coverage. This may be a result of higher Russian focus in post-Soviet occupied territories closer to its borders, which divert Russian media attention away from Republika Srpska. In sum, the Russian government uses its state-owned media to promote the legitimacy of the Government of Republika Srpska, criticize Western actors in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and garner popularity amongst the Bosnian Serb population.

3. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions of Civic Space in Republika Srpska

Restrictions on civic space actors can take various forms. We focus on three common ways to effectively deter or penalize civic participation: (i) harassment or violence initiated by state or non-state actors; (ii) proposal or passage of restrictive legislation or executive branch policies; and (iii) legal action brought by local authorities against civic actors.

In this section, we examine the restrictions faced by civic space actors over time, the initiators, and targets (section 3.1); and the specific nature and types of restrictions of civic space actors throughout the period (section 3.2). Civic space actors in Republika Srpska experienced 36 known restrictions between January 2015 and September 2020 (see Figure 7). These restrictions were heavily weighted towards instances of harassment or violence (86 percent). There were far fewer instances of legal action brought by local authorities (3 percent) and newly proposed or implemented restrictive legislation (11 percent), but these can have a multiplier effect in creating a legal mandate to pursue other forms of restriction. [67]

Figure 7. Recorded Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Republika Srpska

3.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time

Instances of restriction were front-loaded across this time period with the vast majority of restrictions (89 percent) occurring before 2019 (Figure 7). While instances of restrictions were largely consistent from 2015-2018, a spike in instances of restrictions of actors in the civic space coincided with the “Justice for David” protests in late 2018 and 2019. Authorities in Republika Srpska engaged in two types of restrictions during these protests, arresting protest organizers and journalists (violence or harassment) and filing a criminal case against an activist for his role in the protests (legal action brought by local authorities).

Members of the media were more frequently mentioned in recorded instances of restrictions in Republika Srpska than those working for formal CSOs and NGOs, other community groups, or the political opposition (Figure 8). Journalists and other members of the media were the targets in over half (58 percent) of the instances of violence and harassment, whereas formal CSOs and NGOs were more often targeted through restrictive legislation (50 percent of instances).

Figure 8. Recorded Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Republika Srpska by Targeted Group

Number of Instances, January 2015 - September 2020

Figure 9 breaks down the targets of restrictions by political ideology or affiliation in the following categories: pro-democracy, pro-Western, and anti-Kremlin. [68] Pro-democracy organizations and activists were mentioned 11 times as targets of restrictions during this period. [69] Pro-Western organizations and activists were mentioned 1 time as a target of restriction . [70] Anti-Kremlin organizations and activists were mentioned 1 time as a target of restriction . [71]

Figure 9. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Republika Srpska by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015 - September 2020

The Government of Republika Srpska was the most prolific initiator of violence or harassment (68 percent of mentions). These instances most often involved the police, but also by official media outlets, politicians, and bureaucrats who engaged in verbal attacks and threats (Figure 10). [72] For example, in March 2015, President Milorad Dodik verbally insulted a Banja Luka journalist for the Sarajevo daily Oslobodjenje with derogatory comments about their physical appearance and ethnic background. [73]

Outside of the government, threatened or acted-on restrictions related to ethnic background in Republika Srpska were frequent. Two domestic non-governmental organizations and eight unknown individuals were identified as perpetrating acts or threats of violence and harassment, as well. Most of these restrictions were initiated against media outlets and journalists, usually for perceived ethnic ties. In June 2017, two journalists received death threats from the media outlet Bošnjaci.net for reporting on the breaking of the Ramadan fast, and in January 2016, molotov cocktails were thrown by unknown aggressors at a mosque in Pale. Serbian or Bosniak nationalism was behind the majority of instances of violence or harassment by non-government or unknown actors in Republika Srpska.

Figure 10. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Republika Srpska by Initiator

Number of Instances Recorded

3.2 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

Instances of physical harm (4 threatened, 4 acted-on) were outnumbered by the instances of harassment (1 threatened, 22 acted-on) in Republika Srpska between January 2015 and September 2020. The vast majority of these restrictions (84 percent) were acted-on rather than merely threatened, though since this data is collected on the basis of reported incidents, this likely understates threats which are less visible (Figure 11). The most frequent examples included verbal harassment from politicians or the detention of protesters or journalists. Eleven of the 22 instances involved verbal harassment of civil society actors and eight of the 22 instances of acted-on harassment involved the detention of journalists or protesters.

Figure 11. Threatened versus Acted-On Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Republika Srpska

Number of Instances Recorded

Recorded instances of restrictive legislation in Republika Srpska were relatively few in number (4) but are important to capture as they can constrain civic space with long-term cascading effects. This indicator is limited to a subset of “laws”, “decrees”, or other formal policies and rules that may have a deleterious effect on civic space actors, either subgroups or in general. Both proposed and passed restrictions qualify for inclusion, but we focus exclusively on new and negative developments in laws or rules affecting civic space actors. For this reason, we exclude from mention discussion of pre-existing laws and rules or those that constitute an improvement for civic space.

Where CSOs are concerned, the Government of Republika Srpska announced two draft laws in 2015 and 2018 which cast doubt on the legitimacy of foreign-funded NGOs, impeding their ability to organize and raise funds and forcing them to register as “foreign agents.” The first draft law, proposed in May 2015, was nicknamed Putin’s Bill, due to its similarity to a Russian bill passed in 2012. [74] These laws impose a high financial and human cost, acting as a barrier to entry for residents to engage in active civic participation. The two laws in question include:

- 2015 Bill on Foreign-Funded Non-Governmental Organizations (“Putin’s Bill”)

- 2018 Law on Foreign Funding

Regarding the media, in February 2015, the National Assembly of Republika Srpska proposed draft legislation that sought to expand public order laws over social media, limiting the content that individuals can post online. In March 2020, the government introduced a Chief Executive Order that punishes outlets or journalists that “spread panic and publish or transmit fake news on COVID-19.” [75]

CSOs and the media are limited by these legislative developments, which stoke an atmosphere of distrust and unease towards civic space actors. In addition to the laws themselves, the continued aggressive rhetoric against the media and CSOs appears as consent to attack these civic actors.

Republika Srpska had 1 recorded instance of a legal case in January 2019. The case brought against Aleksandar Gluvić, an activist in the aforementioned “Justice for David” protests. Gluvić received a fine and 20 days in prison for his role in the protests. [76] As shown in Figure 12, this case was directly tied to fundamental freedoms (e.g., freedom of speech, assembly).

Figure 12. Direct versus Indirect Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Republika Srpska

Number of Instances Recorded

In sum, authorities in Republika Srpska use restrictions of civic space actors to attack foreign-funded CSOs and local dissenting journalists and activists. These targets highlight that the Government of Republika Srpska is working in the best interests of the Russian government to maintain ties with Russia and limit Western presence in the region.

4. Conclusion

In this supplemental profile, we have demonstrated that the Kremlin uses multiple channels—financial and in-kind support, state-backed media—to influence civic space actors in Republika Srpska. The Russian government appears to orient its activities to promote two narratives which advance its interests.

First, the Russian government promotes the independent power of Republika Srpska’s government and creates a chilling effect on dissent by strengthening local law enforcement, particularly training the local elite military police, and portraying opposition protests negatively.

Second, the Kremlin attempts to discredit Western organizations and civic actors, encouraging the labeling of CSOs that received external funding as “foreign agents” and criticizing institutions created during the Dayton Accords in 1995 as being “humiliating” to Republika Srpska. [77]

Third, the Kremlin appears intent on encouraging Republika Srpska to push for greater autonomy or independence, using it as leverage in the Balkans to expand its own control.