Occupied Territories Supplement

Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence

Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia, Self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic, Self-declared Luhansk People’s Republic, Nagorno-Karabakh, Georgia’s Russia-occupied South Ossetia, Transnistria

Emily Dumont and Lincoln Zaleski

April 2023

Table of Contents

Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia

Self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic

Self-declared Luhansk People’s Republic

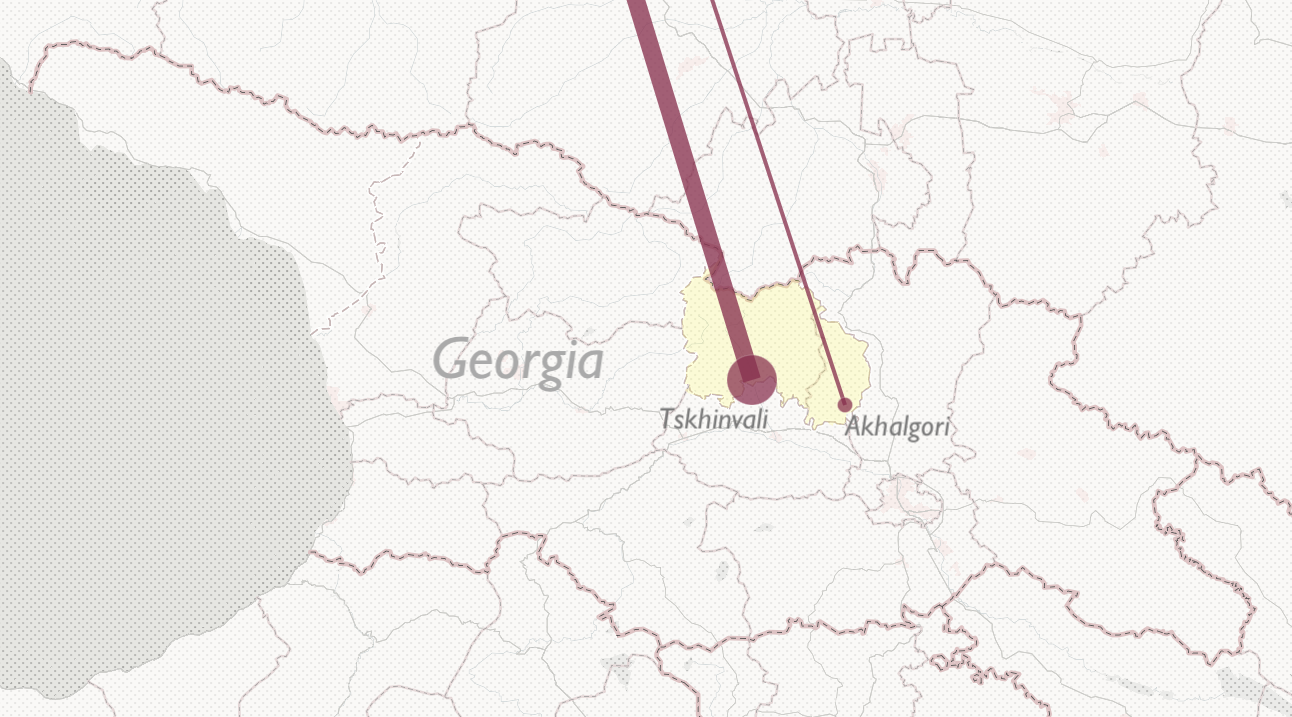

Georgia’s Russia-occupied South Ossetia

Acknowledgments

This supplemental profile was prepared by Emily Dumont and Lincoln Zaleski. John Custer, Sariah Harmer, Parker Kim, and Sarina Patterson contributed editing, formatting, and supporting visuals. We are grateful for Ania Leska’s contribution of fact-checking and editing. We acknowledge the assistance of Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Kelsey Marshall, and our research assistants for their invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report: Jacob Barth, Kevin Bloodworth, Callie Booth, Catherine Brady, Temujin Bullock, Lucy Clement, Jeffrey Crittenden, Emma Freiling, Cassidy Grayson, Annabelle Guberman, Sariah Harmer, Hayley Hubbard, Hanna Kendrick, Kate Kliment, Deborah Kornblut, Aleksander Kuzmenchuk, Amelia Larson, Mallory Milestone, Alyssa Nekritz, Megan O’Connor, Tarra Olfat, Olivia Olson, Caroline Prout, Hannah Ray, Georgiana Reece, Patrick Schroeder, Samuel Specht, Andrew Tanner, Brianna Vetter, Kathryn Webb, Katrine Westgaard, Emma Williams, and Rachel Zaslavsk. The findings and conclusions of this supplement are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

Notes on Vocabulary

The authors recognize the challenge of writing about contexts with ongoing hot and/or frozen conflicts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consistently label groups of people and places for the sake of data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that terminology is political, but our use of terms should not be construed to mean support for one faction over another. For example, the terms Nagorno-Karabakh and Karabakh are used to denote the same enclave inhabited by Karabakh Armenians on the territory of the former Soviet Union Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO). We do not intend for any political meaning related to the conflict to be taken from the use of either term. When we talk about Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia or Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of South Ossetia, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the Georgian government in Tbilisi. When we talk about the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic or the self-declared Luhansk People’s Republic, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the Ukrainian government in Kyiv. When we talk about Transnistria, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the Moldovan government in Chișinău. When we analyze the de facto authorities’ use of legislation or legal action to restrict civic action, it is not to grant legitimacy to separatist movements, or to the de facto legal and judicial institutions of separatists. Rather, our purpose is to glean meaningful insights about the ways in which institutions are co-opted or employed to constrain civic freedoms.

Citation

Dumont, E and Zaleski, L. (2023). Collection of supplemental reports measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence in occupied territories . Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary.

Civic Space Report Occupied Territories Supplement

Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia

Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence

Emily Dumont and Lincoln Zaleski

April 2023

Executive Summary

As a companion to AidData’s main Georgia Country Report, this supplemental profile surfaces insights about the health of civic space and vulnerability to malign foreign influence specific to Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia. The analysis was part of a broader three-year initiative by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to produce quantifiable indicators to monitor civic space resilience in the face of Kremlin influence operations over time and across 17 countries of Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E), including 7 territories that are occupied or autonomous and vulnerable to malign actors.

Below we summarize the top-line findings from our indicators on the channels of Russian malign influence operations, as well as the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia:

- Russian-backed Civic Space Projects: The Kremlin supported 14 Abkhazian civic organizations via 24 civic-space relevant projects between January 2015 and September 2020. Projects emphasized training local “military” units, promoting Russian language and history via compatriot unions, and engaging youth groups. Russian state overtures were primarily oriented towards Sokhumi, the Abkhazian “capital”, which attracted 17 projects. The Kremlin supported a variety of groups—from formal civil society organizations and compatriot unions to schools.

- Russian State-run Media: Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News referenced Abkhazian civic space actors 160 times from January 2015 to March 2021. The lion’s share of mentions were focused on domestic Abkhazian civil society actors. Political parties were the most frequently mentioned Abkhazian organizations. The overall tone of Russian state media coverage of Abkhazian civic actors was largely neutral, though they portrayed opposition parties and protesters more negatively.

- Restrictions of Civic Actors: Abkhazian civic space actors were the targets of 3 recorded restrictions between January 2015 and September 2020. All of these restrictions involved harassment or violence, with no instances of newly proposed or implemented restrictive “legislation” or legal action brought by de facto authorities. Other community groups were the targets in most of the instances of violence and harassment (67 percent). The preponderance of harassment or violence was initiated by the self-declared government of Abkhazia.

A Note on Vocabulary

The authors recognize the challenge of writing about contexts with ongoing hot and/or frozen conflicts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consistently label groups of people and places for the sake of data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that terminology is political, but our use of terms should not be construed to mean support for one faction over another. For example, when we talk about Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the Georgian government in Tbilisi. Or when we analyze the de facto authorities’ legislation or legal action to restrict civic action, it is not to grant legitimacy to the laws or courts of separatists, but rather to glean meaningful insights about the ways in which institutions are co-opted or employed to constrain civic freedoms.

Acknowledgements

This supplemental profile was prepared by Emily Dumont and Lincoln Zaleski. John Custer, Sariah Harmer, Parker Kim, and Sarina Patterson contributed editing, formatting, and supporting visuals. We acknowledge the assistance of Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Kelsey Marshall, and our research assistants for their invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report: Jacob Barth, Kevin Bloodworth, Callie Booth, Catherine Brady, Temujin Bullock, Lucy Clement, Jeffrey Crittenden, Emma Freiling, Cassidy Grayson, Annabelle Guberman, Sariah Harmer, Hayley Hubbard, Hanna Kendrick, Kate Kliment, Deborah Kornblut, Aleksander Kuzmenchuk, Amelia Larson, Mallory Milestone, Alyssa Nekritz, Megan O’Connor, Tarra Olfat, Olivia Olson, Caroline Prout, Hannah Ray, Georgiana Reece, Patrick Schroeder, Samuel Specht, Andrew Tanner, Brianna Vetter, Kathryn Webb, Katrine Westgaard, Emma Williams, and Rachel Zaslavsk. The findings and conclusions of this supplement are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

This research was made possible with funding from USAID's Europe & Eurasia (E&E) Bureau via a USAID/DDI/ITR Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) cooperative agreement (AID-A-12-00096). The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

Citation

Dumont, E., Zaleski, L. (2023). Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence. Occupied Territories Supplemental Profile. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary.

1. Introduction

The Russian government supports occupied territories as a tactic to weaken perceived adversaries and further its influence in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. [1] As a companion to AidData’s main Georgia Country Report, this supplemental profile examines the Kremlin’s tools of influence in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia’s civic space [2] which seek to manipulate local attitudes in support of three key narratives which advance its interests.

First, the Kremlin bolsters pro-Russian sentiment in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia by using its state-owned media to amplify, and its state institutions to finance Russian cultural and historical connections between Sokhumi and Moscow. Second, the Kremlin attempts to discredit Western and Georgian organizations in the territory, criticizing organizations like the European Union Monitoring Mission in Georgia. Finally, the Kremlin promotes the status quo in the territory, encouraging a crackdown on dissent, which the Sokhumi self-declared government backs up through restrictions of political opponents.

This profile is part of a broader three-year research effort conducted by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to collect and analyze vast amounts of historical data on civic space and Russian influence across 17 countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E), including 7 territories that are occupied or autonomous and vulnerable to malign actors. For the purpose of this project, we define civic space as: the formal laws, informal norms, and societal attitudes which enable individuals and organizations to assemble peacefully, express their views, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction.

In the remainder of this supplemental profile, we provide additional details on how the Russian government uses its state institutions to influence the Abkhazian population in support of these narratives. In section 2, we examine Russian projectized support relevant to civic space and analyze Russian state-backed media mentions of civic space actors. In section 3, we enumerate restrictions of civic space actors. A methodology document is available via aiddata.org.

Table 1. Quantifying External Influence on and Restrictions of Civic Space

|

Civic Space Barometer |

Supporting Indicators |

|

Russian state financing and in-kind projectized support relevant to civic space actors or regulators (January 2015-September 2020) |

|

|

Russian state media mentions of civic space actors or democratic rhetoric (January 2015-March 2021) |

|

|

Restrictions of civic space actors (January 2017-September 2020) |

|

Notes: Table of indicators collected by AidData to assess the health of Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia’s domestic civic space and vulnerability to Russian influence. Indicators are categorized by barometer (i.e., dimension of interest) and specify the time period covered by the data in the subsequent analysis.

2. External Channels of Influence: Kremlin Civic Space Projects and Russian State-Run Media

In this project, we tracked financing and in-kind support from Kremlin-affiliated agencies to: (i) build the capacity of those that “regulate” the activities of civic space actors; and (ii) co-opt the activities of civil society actors within E&E countries in ways that seek to promote or legitimize Russian policies abroad. The Kremlin supported 14 known Abkhazian civic organizations via 24 civic space-relevant projects during the period of January 2015 to September 2020. In section 2, we unpack more specifics on the suppliers (section 2.1), recipients (section 2.2), and focus of Russian state-backed support to the Abkhazian civic space (section 2.3).

Since E&E countries are exposed to a high concentration of Russian state-run media, we analyzed how the Kremlin may use its coverage to influence public attitudes about civic space actors (formal organizations and informal groups), as well as public discourse pertaining to democratic norms or rivals in the eyes of citizens. Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced civic actors in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia a total of 160 times from January 2015 to March 2021. The majority of these mentions (117 instances) were of domestic civic space actors, while the remaining portion (43 instances) consisted of mentions of foreign and intergovernmental actors in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia. Russian state media covered a diverse set of civic actors, mentioning 24 organizations by name, as well as 17 informal groups operating in the territory.

In this section, we examine how Russian state media characterizes both domestic and external actors in the Abkhazian civic space. We examine Russian state media coverage of domestic (section 2.4) and external (section 2.5) actors in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia’s civic space, and how this has evolved over time (section 2.6).

2.1 The Suppliers of Russian State-Backed Support to Civic Space

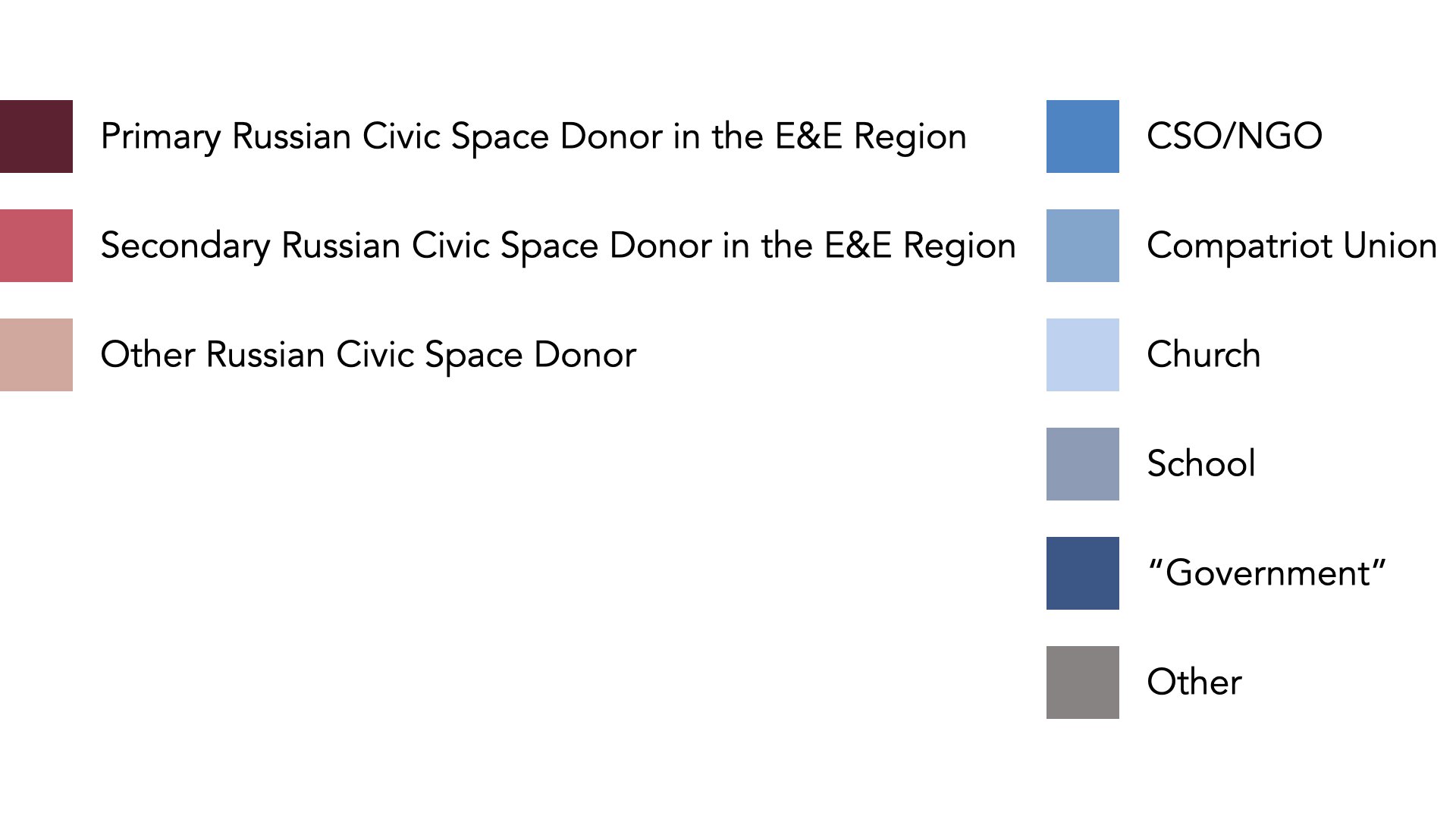

Moscow prefers to directly engage and build relationships with individual civic actors in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia—training local “military” units, promoting Russian language and history via compatriot unions, and engaging youth groups—as opposed to investing in broader based institutional development. The Russian government’s interest in cultivating these relationships with Abkhazian civic actors increased in frequency throughout the period (Figure 1) and its support primarily financed cultural programs aimed at bridging ties between the Abkhazian and Russian populations.

Figure 1. Russian Projects Supporting Civic Space Actors by Type

Number of Projects Recorded, January 2015 - September 2020

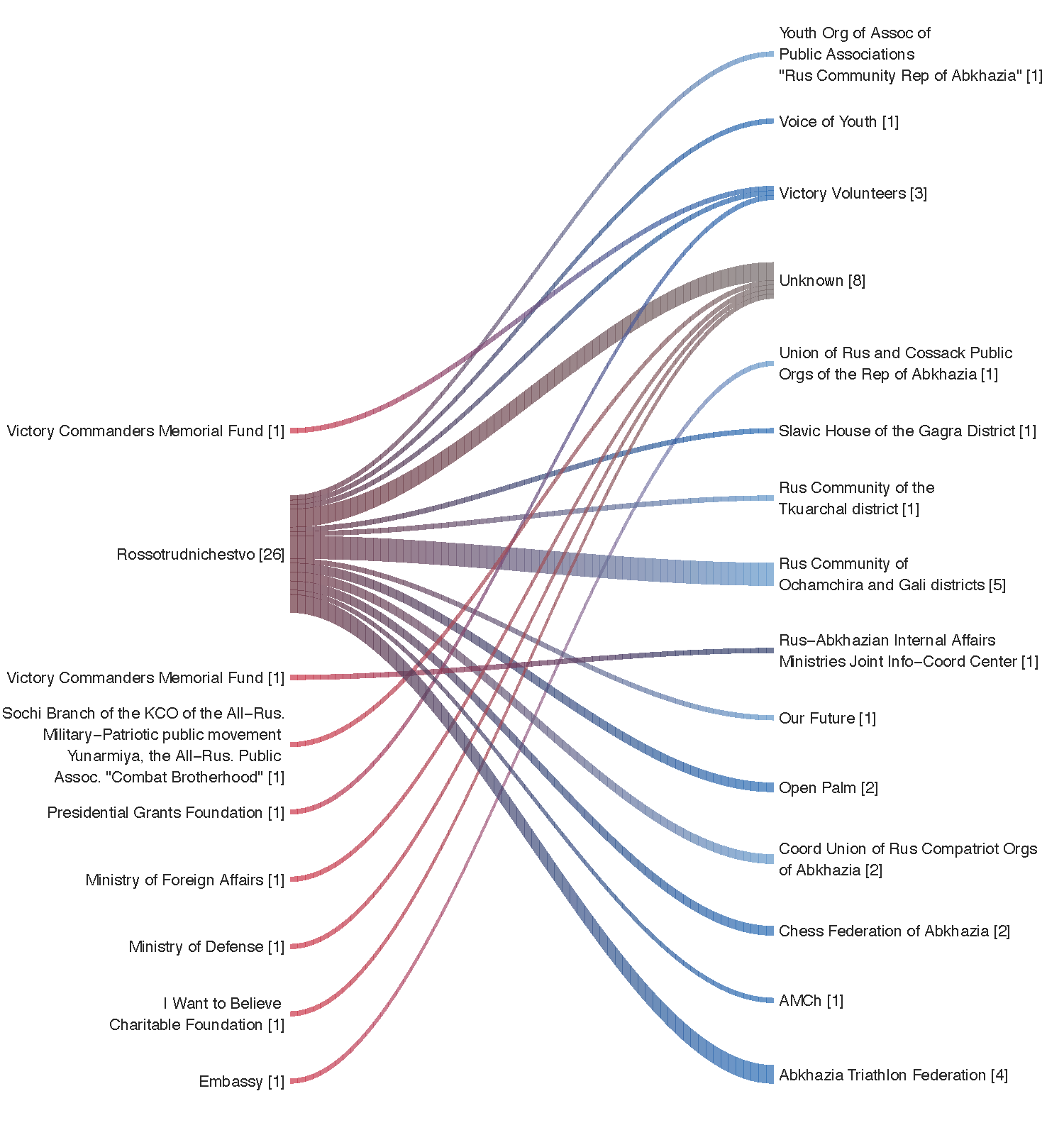

The Kremlin routed its engagement in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia through 7 different channels (Figure 2), which included numerous Russian government ministries, federal centers, language and culture-focused funds, and the Embassy in Sokhumi. The stated missions of these Russian government entities focus on defense, education and culture, and public diplomacy. Civil society development was more often a supporting theme than the primary purpose of most of these entities.

Rossotrudnichestvo [3] —an autonomous agency under the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs with a mandate to promote political and economic cooperation abroad—is associated with the vast majority (92 percent) of the Kremlin’s overtures to Abkhazian civic actors. Rossotrudnichestvo has an office in Sokhumi, the “capital” of Abkhazia, potentially explaining the Russian agency’s influence in the territory.

Two Russian ministries financing projects in the territory—the Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Foreign Affairs—focused on training of “security forces”. Both Russian ministries financed “military” training sessions for Abkhazian cadets and youth in Gudauta. The stated goals of this training were to “educate and strengthen in the minds of adolescents the rejection of violence, the formation of a negative attitude towards terrorism, extremism in all forms.” [4] The continued presence of the Russian military in the territory, now as occupying forces, likely bolsters the Kremlin’s influence in the security sphere and, by extension, constrain civic space actors that would be threatening to its interests. [5]

Additionally, Russian non-governmental organizations joined forces with Russian government entities to finance and plan a series of military and political trainings in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia. Since this profile focuses on official Russian government actors, it provides an initial baseline of Kremlin support to civic space actors in the territory, but likely undercounts the full universe of such relationships.

Figure 2. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Civic Space Actors

Number of Projects, 2015-2020

2.2 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Civic Space

Russia supported a variety of actors in the Abkhazian civic space between January 2015 and September 2020. These include formal civil society organizations (CSOs), compatriot unions for the Russian diaspora in the territory, [6] and academic schools. The Abkhazian Ministry of Internal Affairs is the only known agency of the self-declared government that received projectized support from the Kremlin, through the Russian-Abkhazian Internal Affairs Ministries Joint Information-Coordination Center. Additionally, a Kremlin-sponsored training for young professionals included employees from a number of purported ministries and departments of Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia.

Over one-third of recipient organizations were Russian compatriot organizations in the territory. Joint Russian government and compatriot organization events highlight how the Kremlin promotes historical and cultural narratives amongst the Russian diaspora in the territory. For example, events with diaspora compatriot organizations in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia included handing out Russian flag ribbons for the Day of the State Flag of the Russian Federation in August 2017 and a concert with traditional Russian singers for the Day of Russia in June 2018. Taken together with Russian state-owned media narratives (which will be discussed below), the Kremlin appears to use its financial resources to generate support for its continued presence in the territory through shared history and culture, starting with the Russian ethnic population.

Formal civil society organizations (CSOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) were the most frequent recipients of Russian projectized support to the territory (46 percent of flows). These organizations were often oriented towards sports and exercise, with the Triathlon Federation and Chess Federation of Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia receiving over half of all support to CSOs and NGOs. The Russian government often offered support for events such as a Victory Day cycling race or a Day of Russia chess tournament, tying in Russian holidays and celebrations into engagement with the civic space.

Geographically, Russian state overtures were primarily oriented towards Sokhumi. Seventeen of the 24 identified projects were located in the Abkhazian “capital”. Six events were held in Ochamchire, including Russian-sponsored concerts and celebrations for Black Sea Day, the Day of National Unity, and Day of Russia. Three events distributing St. George ribbons were held in Tkvarcheli. One event, a youth “military” training in August 2018, was held in Gudauta. Lastly, Rossotrudnichestvo sponsored an education program for Abkhazian youth in December 2018 for Abkhazian students at the Southern Federal University in Russia, which was attributed to the territory at-large.

Figure 3. Locations of Russian Support to Civic Space Actors

Number of Projects, 2015-2020

|

Recipient Organization Subnational Location |

Project Counts |

|

Abkhazia (Unspecified) |

1 |

|

Gudauta |

1 |

|

Ochamchire |

5 |

|

Ochamchire, Sokhumi, Tkvarcheli |

1 |

|

Sokhumi |

14 |

|

Sokhumi, Tkvarcheli |

2 |

|

Total |

24 |

2.3 The Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Civic Space

With a few notable exceptions, Russian support to civic space actors in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia appears to be weighted toward non-financial support rather than direct transfers of funding. Over 95 percent of the projects identified (23 projects) did not explicitly describe receiving grants. Instead, Russian actors supplied various forms of non-financial “support” such as training, technical assistance, and other in-kind contributions to its partners.

One of the main types of Russian assistance was support for cultural events. This support typically appeared in the form of space, materials, or other logistical and technical contributions to local partners via organs such as Rossotrudnichestvo or the Presidential Grants Foundation. In particular, Rossotrudnichestvo provided support for all 19 Russian state assisted events in the territory. The majority of events that received Kremlin support promoted Russian culture and history.

The Russian government additionally funded both political and military training for youth in the territory. Through sponsored political trainings and youth “military” training from the Russian Defense Ministry, children in the territory were the target audiences for pro-Russian doctrine and early “military” education.

Kremlin-backed organizations in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia focused on providing assistance to organizations that focused on youth, “military”, history, and culture. This trend shows a significant investment in shaping the future of the territory, as training future fighters and implementing Russian-backed historical education campaigns may highlight that Russia has no intention of solving the frozen conflict between Georgia and the territory. Rather, through its financial influence in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia, the Kremlin seems to double-down on the institutions that support its presence in the region: the “military”, Russian compatriot organizations, and pro-Russian education.

2.4 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Civic Space Actors

Roughly a quarter (17 percent) of Russian media mentions pertaining to domestic actors in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia’s civic space referred to specific groups by name. The 13 named domestic actors represent a diverse cross-section of organizational types, ranging from political parties to formal civil society organizations to media outlets. Political parties were the most frequently mentioned organization type (10 mentions), followed by formal civil society or non-governmental organizations (5 mentions). Opposition parties, including the Bloc of Opposition Forces (4 mentions) and the Amtsakhara Party (3 mentions), made up the majority of domestic political party mentions.

Russian state media mentions of specific civic space actors in the territory were predominantly neutral (80 percent) in tone. The remaining sentiment consisted of 3 “somewhat negative” mentions (15 percent) and 1 “somewhat positive” mention (5 percent). All three “somewhat negative” mentions were attributed to parties in opposition for inciting protests. The Amtsakhara Party (1 negative mention) and Bloc of Opposition Forces (1 negative mention) encouraged protests to support current de facto President Aslan Bzhania when he was in opposition, and the Coordinating Council of Political Parties and Public Organizations (1 negative mention) supported former de facto President Raul Khajimba rise to power through protests as well. Although the self-declared administrations changed over the time frame, Russian coverage of the various parties behind opposition-backed protests remained “somewhat negative,” as the Kremlin appeared wary of protest movements in the territory.

Aside from these named organizations, TASS and Sputnik made 97 generalized mentions of 10 informal civic groups during the same period. Coverage of these organizations was predominantly neutral (63 percent) as well. The remaining mentions consisted of both negative coverage, with 25 “somewhat negative” mentions (26 percent) and 6 “extremely negative” mentions (6 percent), and positive coverage, with 4 “somewhat positive” mentions (4 percent) and 1 “extremely positive” mention (1 percent). In line with negative coverage of opposition parties above, Russian state media assigned all 25 “somewhat negative” and 6 “extremely negative” mentions of informal domestic civic groups to opposition movements and protesters. Russian state media criticized opposition-backed protesters in the territory, in one case stating, “Storming the republic’s Interior Ministry began at a moment when we were meeting the opposition representatives. It’s nothing short of treachery. We’ll do everything possible to prevent such incidents in the future." [7]

Notably, Russian state media assigned positive coverage to three informal domestic civic groups as well: civil society institutions (2 positive mentions), liberation movement (2 positive mentions), and folklore groups (1 positive mention). This positive coverage is in line with Russian state media narratives in other occupied territories, as Russia promotes the continued separation of the territory from Georgia through encouraging local culture, such as through folklore groups, and canonizing the liberation movement. By promoting separate civil society institutions, encouraging separate cultural identities, and rewriting the war effort to sound positive, Russian state media attempts to make Abkhazian residents less likely to ever support returning to Georgia.

When considering the domestic civic actors in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia as a whole, there are two trends surrounding their coverage by Russian state media. First, Russian state media assigned negative coverage to local dissenters and opposition groups. Second, positive coverage is attributed to institutions that encourage territory’s “independence”, such as civil society institutions and cultural groups. These trends are reflected in the top mentioned domestic organizations.

As noted, opposition parties, including Amtsakhara and the Bloc of Opposition Forces, and protesters received the vast majority of negative coverage from Russian state media. This is consistent with findings across other occupied territories, as the Russian government seeks to promote the frozen status of occupied territories through its state-owned media by discouraging dissent.

Figure 4. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors by Sentiment

Number of Mentions, January 2015 - March 2021

2.5 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in Abkhazian Civic Space

Russian state media dedicated the remaining mentions (43 instances) to external actors in the Abkhazian civic space. [8] TASS and Sputnik mentioned 8 intergovernmental organizations (15 mentions) and 4 foreign organizations (11 mentions) by name, as well as 6 general foreign actors (17 mentions). External organizations monitoring “elections” and security threats in the territory and Russian media outlets reporting in the region dominated the external mentions.

Russian state-owned media mentioned international ”election” observers most often when referencing the civic space of the territory (9 mentions). These observers received entirely neutral coverage and were mostly from Russia and other Commonwealth of Independent States countries. Notably, Russian “Peacekeepers” in the territory received some positive attention from Russian state-owned media, whereas the European Union Monitoring Mission received negative coverage. Russian state media assigning negative coverage to Western actors and positive coverage to Russian actors is a consistent trend among former Soviet occupied territories.

Figure 5. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors by Sentiment

Number of Mentions, January 2015 - March 2021

Mentions of foreign and intergovernmental civic actors involved in the territory were predominantly neutral (72 percent). The remaining mentions consisted of 7 “somewhat negative” (16 percent) and 5 “somewhat positive” mentions (12 percent).

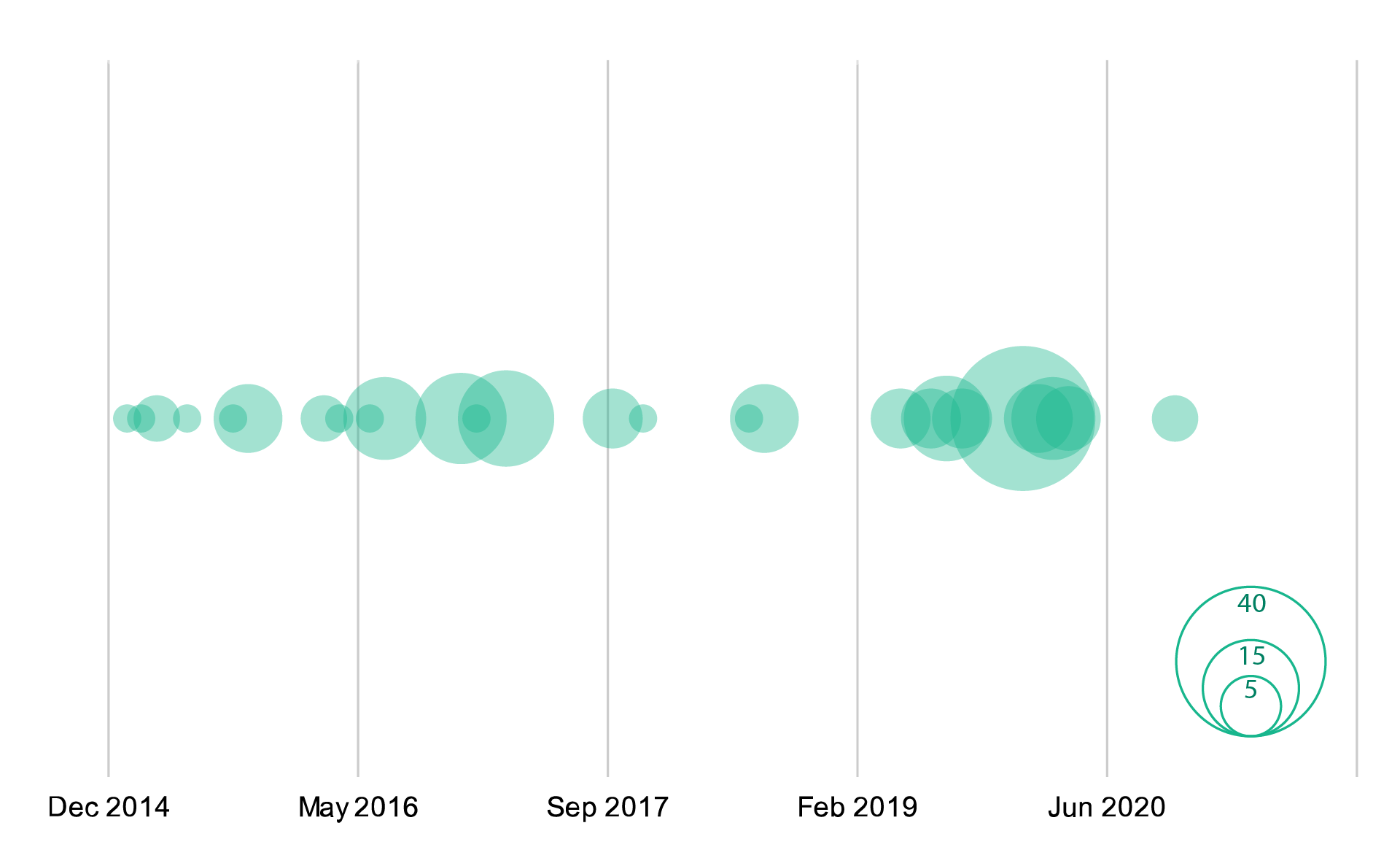

2.6 Russian State Media’s Focus on Civic Space over Time

For many of the occupied territories, Russian state media mentions spike around major events and tend to show up in clusters. This remains true in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia, with spikes in mentions related to protests to the early presidential ”election” in July 2016, the arrest of Aslan Bzhania in December 2016, the parliamentary “elections” in March 2017, and the August 2019 Presidential ”election”, which sparked protests and another ”election” in early 2020. The highest spike in mentions was in January 2020, when the Abkhazian “Supreme Court” annulled the August 2019 Presidential ”election” in response to ongoing mass protests.

Figure 6. Russian State Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

Number of Mentions Recorded

Major events in Russian state media mentions of the Abkhazian civic space can be broken down between protests and “elections”. Three key protest events in July 2016, December 2016, and January 2020 accounted for 65 total mentions (41 percent). Of these mentions, 27 were negative (42 percent). During the parliamentary “elections” in March 2017 and the presidential “elections” in August 2019 and March 2020, Russian state media made 36 mentions of civic actors (23 percent of all mentions) and attributed only neutral coverage to these organizations. This trend highlights the focus of the Russian government on cracking down on dissent within the territory through its state-owned media.

Russian state media coverage of civic actors in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia highlights some interesting takeaways. First, protesters and opposition groups, regardless of political belief or supported leader, received negative coverage from Russian state-owned media. The Russian government seeks to continue the territory’s status of de facto “independence”, and uses its state-owned media to dissuade residents from dissenting against the “Abkhazian authorities”. By preventing political fractures, the Russian government can discourage Georgia from taking advantage of Abkhazian weaknesses and maintain control over the occupied territory. Second, Russian state-owned media covered Western institutions working in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia negatively. While Western actors received significantly less coverage than in other occupied territories, when institutions such as the European Union Monitoring Mission in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia were mentioned, they were covered negatively. This is a consistent trend across occupied territories and highlights the Kremlin’s goal of maintaining the heavy Russian influence over the territory’s civic space and governance by sowing discord and doubt.

3. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions of Civic Space

Restrictions on civic space actors can take various forms. We focus on three common ways to effectively deter or penalize civic participation: (i) harassment or violence initiated by state or non-state actors; (ii) proposal or passage of restrictive “legislation” or executive branch policies; and (iii) legal action brought by de facto authorities against civic actors.

In this section, we examine the restrictions faced by civic space actors over time, the initiators, and targets (section 3.1); and the specific nature and types of restrictions of civic space actors throughout the period (section 3.2). Abkhazian civic space actors experienced 3 known restrictions between January 2015 and September 2020 (Figure 7). These restrictions were heavily weighted towards instances of harassment or violence (100 percent). There were no instances of legal action brought by de facto authorities or newly proposed or implemented restrictive “legislation”. [9] In the remainder of this section, we examine: the restrictions over time, the initiators, and targets (section 3.1); and the specific nature and types of restrictions of civic space actors throughout the period (section 3.2).

Figure 7. Recorded Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

3.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time

Instances of restriction were front-loaded across this time period with all restrictions (100 percent) occurring before 2018 (Figure 7). No counts of restriction were recorded after 2017 in the territory. Other community groups and political opposition were the only mentioned targets of restriction (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Recorded Restrictions of Civic Space Actors by Targeted Group

Number of Instances, January 2015 - September 2020

Figure 9 breaks down the targets of restrictions by political ideology or affiliation in the following categories: pro-democracy, pro-Western, and anti-Kremlin. [10] Pro-democracy organizations and activists were mentioned 3 times as targets of restriction during this period. [11] Pro-Western organizations and activists were not mentioned as targets of restrictions . [12] Anti-Kremlin organizations and activists were not mentioned as targets of restrictions . [13]

Figure 9. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015 - September 2020

The self-declared government of Abkhazia was the most prolific initiator of harassment or violence, with 67 percent of mentions (Figure 10). In 2015 and 2016, de facto authorities seized Abkhazian passports of ethnic Georgians residing in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Territory of Abkhazia, preventing them from voting in local, presidential, or parliamentary “elections”. Further issues persisted in March 2017, as “elections” were marred by instances of voter intimidation and attacks against opposition candidates.

Figure 10. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors by Initiator

Number of Instances Recorded

3.2 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

There were 2 instances of acted-on harassment of civic space actors and 1 instance of acted-on violence against civic space actors recorded between 2015 and 2020. Since this data is collected on the basis of reported incidents, this data likely understates threats which are less visible (see Figure 11). The most frequent type of harassment included seizures of passports from ethnic Georgians, preventing them from voting (2 instances).

One instance of acted-on violence towards civic space actors was recorded in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia, as two members of the political opposition were attacked by unknown forces during the parliamentary “elections” in March 2017. [14]

Figure 11. Acted-On Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors

Number of Instances Recorded

There were no recorded instances of restrictive “legislation” in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia or legal action brought by de facto authorities between January 2015 and September 2020. In general, the Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia scores higher on civil liberties and political freedoms than any other occupied territory in Europe and Eurasia. [15]

4. Conclusion

In this supplemental profile, we demonstrate that the Kremlin uses multiple channels—financial and in-kind support, state-backed media—to influence Abkhazian civic space actors. The Russian government appears to orient its activities to promote three narratives which advance its interests.

First, the Kremlin bolsters pro-Russian sentiment in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia by using its state-owned media to amplify and its state institutions to finance Russian cultural and historical connections between Sokhumi and Moscow. By providing support to Russian compatriot institutions and promoting revisionist cultural and historical ties between Russia and the territory, the Kremlin seeks to extend its influence over not only the institutions of Sokhumi, but also the hearts and minds of the Abkhazian population.

Second, the Kremlin attempts to discredit Western and Georgian organizations in the territory, criticizing organizations like the European Union Monitoring Mission in Georgia. Negative coverage of Georgian actors by Russian media in the territory likely contributes to the self-declared Abkhazian government denying ethnic Georgians a right to vote. As such, through state-owned media, the Kremlin discredits Western and Georgian groups that may threaten Russia’s influential position in the territory.

Finally, the Kremlin promotes the status quo in Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of Abkhazia, encouraging a crackdown on dissent, which the de facto authorities in Sokhumi backs up through restrictions of ethnic Georgians and political opponents. Negative coverage of protesters and other dissenters is a common trope in Russian state-owned media, encouraging local restrictions of political opposition and other critical civic space actors.

As highlighted in the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin leverages occupied territories as a tool for expanding its control. By blocking dissenters and Western organizations and bolstering pro-Russian sentiment in the region, the Kremlin intends to maintain Abkhazia’s occupied status, using it as leverage over Georgia.

Civic Space Report Occupied Territories Supplement

Self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic

Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence

Emily Dumont and Lincoln Zaleski

April 2023

Executive Summary

As a companion to AidData’s main Ukraine Country Report, this supplemental profile surfaces insights about the health of civic space and vulnerability to malign foreign influence specific to the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic. The analysis was part of a broader three-year initiative by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to produce quantifiable indicators to monitor civic space resilience in the face of Kremlin influence operations over time and across 17 countries of Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E), including 7 territories that are occupied or autonomous and vulnerable to malign actors.

Below we summarize the top-line findings from our indicators on the channels of Russian malign influence operations, as well as the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Donetsk:

- Russian-backed Civic Space Projects: The Russian government channeled financing and in-kind support to two Donetsk recipient organizations via one civic space-relevant project between January 2015 and September 2020. The project emphasized training and support for labor and trade unions. Russian state overtures were oriented towards formal civil society organizations in Donetsk, the “capital” of the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR).

- Russian State-run Media: The Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News referenced Donetsk civic space actors 925 times between January 2015 and March 2021, providing disproportionately greater attention, as this number is higher than Russian state-run media coverage of civic space actors in entire countries in the E&E region. Only Ukrainian (Kyiv) and Belarussian civic space actors were referenced more often. Media organizations were the most frequently mentioned Donetsk organizations, followed by other community organizations. The overall tone of mentions was largely neutral, though Russian state media frequently provided positive coverage to local groups protesting against the Ukrainian government in Kyiv.

- Restrictions of Civic Actors: Donetsk civic space actors were the targets of 20 known restrictions between January 2017 and March 2021. Eighty percent of these restrictions involved harassment or violence, followed by legal action brought by de facto authorities (15 percent) and newly proposed or implemented restrictive “legislation” (5 percent). Community groups were most often the targets in instances of violence and harassment (44 percent). The preponderance of instances of harassment or violence was initiated by the self-declared government of Donetsk.

A Note on Vocabulary

The authors recognize the challenge of writing about contexts with ongoing hot and/or frozen conflicts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consistently label groups of people and places for the sake of data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that terminology is political, but our use of terms should not be construed to mean support for one faction over another. For example, when we talk about the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the Ukrainian government in Kyiv. Or when we analyze the de facto authorities’ legislation or legal action to restrict civic action, it is not to grant legitimacy to the laws or courts of separatists, but rather to glean meaningful insights about the ways in which institutions are co-opted or employed to constrain civic freedoms

Acknowledgements

This supplemental profile was prepared by Emily Dumont and Lincoln Zaleski. John Custer, Sariah Harmer, Parker Kim, and Sarina Patterson contributed editing, formatting, and supporting visuals. We are grateful for Ania Leska’s contribution of fact-checking and editing. We acknowledge the assistance of Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Kelsey Marshall, and our research assistants for their invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report: Jacob Barth, Kevin Bloodworth, Callie Booth, Catherine Brady, Temujin Bullock, Lucy Clement, Jeffrey Crittenden, Emma Freiling, Cassidy Grayson, Annabelle Guberman, Sariah Harmer, Hayley Hubbard, Hanna Kendrick, Kate Kliment, Deborah Kornblut, Aleksander Kuzmenchuk, Amelia Larson, Mallory Milestone, Alyssa Nekritz, Megan O’Connor, Tarra Olfat, Olivia Olson, Caroline Prout, Hannah Ray, Georgiana Reece, Patrick Schroeder, Samuel Specht, Andrew Tanner, Brianna Vetter, Kathryn Webb, Katrine Westgaard, Emma Williams, and Rachel Zaslavsk. The findings and conclusions of this supplement are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

Citation

Dumont, E., Zaleski, L. (2023). Donetsk People’s Republic: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence in the lead up to war. Occupied Territories Supplemental Profile. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary.

1. Introduction

The Kremlin established a breakaway “government” in Donetsk, following its occupation by Russia, as a tactic to weaken perceived adversaries and further its influence in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. [16] The Kremlin appears to have two overarching goals for its overtures in Donetsk: fostering a Donetsk civic space independent of Ukraine and discrediting Ukrainian organizations in Donetsk.

As a companion to AidData’s main Ukraine Country Report, this supplemental profile examines the Kremlin’s tools of influence in Donetsk’s civic space [17] which seek to manipulate local attitudes in support of two key narratives. First, the Russian government focuses on supporting Donetsk’s “independence” from Ukraine by fostering a distinct identity for Donetsk via media outlets, labor unions, and other civil society organizations. Second, the Kremlin criticizes Ukrainian or pro-Ukrainian organizations in Donetsk, discrediting officials and driving a wedge between the Ukrainian and Donetsk civil societies.

This profile is part of a broader three-year research effort conducted by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to collect and analyze vast amounts of historical data on civic space and Russian influence across 17 countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E), including 7 territories that are occupied or autonomous and vulnerable to malign actors. For the purpose of this project, we define civic space as: the formal laws, informal norms, and societal attitudes which enable individuals and organizations to assemble peacefully, express their views, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction.

In the remainder of this supplemental profile, we provide additional details on how the Russian government uses its state institutions to influence the Donetsk population in support of these narratives. In section 2, we examine Russian projectized support relevant to civic space and analyze Russian state-backed media mentions of civic space actors. In section 3, we enumerate restrictions of civic space actors. A methodology document is available via aiddata.org.

Table 1. Quantifying External Influence on and Restrictions of Donetsk’s Civic Space

|

Civic Space Barometer |

Supporting Indicators |

|

Russian state financing and in-kind projectized support relevant to civic space actors or regulators (January 2015-September 2020) |

|

|

Russian state media mentions of civic space actors or democratic rhetoric (January 2015-March 2021) |

|

|

Restrictions of civic space actors (January 2017-March 2021) |

|

Notes: Table of indicators collected by AidData to assess the health of Donetsk’s domestic civic space and vulnerability to Russian influence. Indicators are categorized by barometer (i.e., dimension of interest) and specify the time period covered by the data in the subsequent analysis.

2. External Channels of Influence: Kremlin Civic Space Projects and Russian State-Run Media in Donetsk

In this project, we tracked financing and in-kind support from Kremlin-affiliated agencies to: (i) build the capacity of those that “regulate” the activities of civic space actors; and (ii) co-opt the activities of civil society actors within E&E countries in ways that seek to promote or legitimize Russian policies abroad. The Kremlin supported 2 known Donetsk civic organizations—both trade unions—via 1 civic space-relevant project during the period of January 2015 to September 2020. Specifically, the Russian government financed training for two student trade union organizations in 2019. In section 2, we unpack more specifics on the suppliers (section 2.1), recipients (section 2.2), and focus of Russian state-backed support to Donetsk’s civic space (section 2.3).

Since E&E countries are exposed to a high concentration of Russian state-run media, we analyzed how the Kremlin may use its coverage to influence public attitudes about civic space actors (formal organizations and informal groups), as well as public discourse pertaining to democratic norms or rivals in the eyes of citizens. Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced civic actors in Donetsk a total of 925 times from January 2015 to March 2021. The majority of these mentions (496 instances) were of domestic actors, while the remaining portion (429 instances) consisted of mentions of foreign and intergovernmental civic space actors in Donetsk. Russian state media covered a diverse set of civic actors, mentioning 52 organizations by name, as well as 32 informal groups operating in Donetsk’s civic space. We examine Russian state media coverage of domestic (section 2.4) and external (section 2.5) actors in Donetsk’s civic space, and how this has evolved over time (section 2.6).

2.1 The Suppliers of Russian State-Backed Support to Donetsk’s Civic Space

The Kremlin routed its engagement in Donetsk through only one channel, the Gorchakov Fund, [18] which promotes Russian culture and provides projectized support to non-governmental organizations to bolster Russia’s image abroad. No identified Russian organization in Donetsk had a relationship to security or security training. However, the continued presence of the Russian military in Donetsk, now as occupying forces, is an indication of the Kremlin’s influence in the security sphere.

Russian state media also mentions flows of support from Russian non-governmental organizations into Donetsk; however, these relationships are outside the scope of this report. For example, organizations like the Humanitarian Battalion of Novorossiya have provided significant support to Donetsk, particularly in humanitarian aid. [19] In this respect, this profile provides an initial baseline of Kremlin support to civic space actors in Donetsk, but likely undercounts the full universe of such relationships.

2.2 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Donetsk’s Civic Space

Students and employees from two labor organizations—the Trade Union of Education and Science Workers of the Donetsk People’s Republic and GOU VPO “Donetsk Academy of Management and Civil Service under the Head of the Donetsk People's Republic”—received event support and political training from the Russian government. Noticeably, Russian state media further reinforced these partnerships through providing positive coverage of local labor unions (see section 2.6). No known self-declared “Donetsk government” agencies received projectized support from the Kremlin for civic space projects. Geographically, Russian state overtures were oriented towards Donetsk, the “capital” of the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic.

2.3 The Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Donetsk’s Civic Space

Russian support to civic space actors in Donetsk appears to be non-financial, rather than direct transfers of funding. The sole project identified did not explicitly describe receiving grants. Instead, Russian actors supplied various forms of non-financial “support” such as training and event support. Through its support to trade and labor organizations, the Kremlin seeks to promote a distinct and independent civic space in Donetsk, and diminish Kyiv’s influence over the occupied territory. Additionally, a number of Russian projects fell outside of the parameters for inclusion in this report, meaning that Russian financing and partnerships with civic space actors in Donetsk to promote further autonomy from Ukraine are likely undercounted.

2.4 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Civic Space Actors in Donetsk

The vast majority (79 percent) of Russian media mentions pertaining to domestic actors in Donetsk’s civic space referred to specific groups by name. The 14 named domestic actors represent a diverse cross-section of organizational types, ranging from political parties to civil society organizations to media outlets. Media organizations were the most frequently mentioned organization type (384 mentions), followed by other community organizations (5 mentions). The domestic “state-run” news agency of self-declared Donetsk, Donetsk News Agency, accounted for the high number of media organizations, with Russian state media citing reports from the Donetsk News Agency as a domestic source 379 times.

In our sample of Russian state media articles, mentions of specific Donetsk civic space actors were predominantly neutral (99 percent) in tone. The activist group Immortal Regiment attracted more positive coverage in relation to an annual celebration of the Soviet Union’s victory in World War II. The sole negative mention was in regards to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate, as Russian state media quoted Ukrainian officials stating that they had detained two clergymen for their role in abetting a terrorist organization. [20]

Aside from these named organizations, TASS and Sputnik made 102 generalized mentions of 11 informal civic groups during the same period. Coverage of these organizations was predominantly neutral (81 percent) as well. Three informal domestic civic groups attracted positive coverage from Russian state media: protesters (9 positive mentions), “independence” supporters (4 positive mentions), and trade unions (1 positive mention). The positive coverage of Donetsk protesters and “independence” supporters rallying against the Kyiv government and Ukrainian forces highlights Russian attempts to discredit Ukrainian authorities amongst Donetsk residents. Similarly, trade unions in Donetsk received positive coverage for filing lawsuits against the Ukrainian government for overdue salaries.

When considering the domestic civic actors in Donetsk as a whole, there are two trends surrounding their coverage by Russian state media. First, the Kremlin’s narratives focused on Ukrainian mistreatment of Donetsk civic space actors. Second, positive coverage is attributed to civic space organizations that highlight Donetsk’s independent civic space from Ukraine, such as citing Donetsk media outlets and journalists rather than Ukrainian outlets. These trends are reflected in the top mentioned domestic organizations.

Figure 1. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in Donetsk by Sentiment

Number of Mentions, January 2015 to March 2021

2.5 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in Donetsk’s Civic Space

Russian state media dedicated the remaining mentions (429 instances) to external actors in the Donetsk civic space. [21] TASS and Sputnik mentioned 6 intergovernmental organizations (203 mentions) and 33 foreign organizations (137 mentions) by name, as well as 21 general foreign actors (89 mentions). Foreign media outlets and international conflict monitors dominated the external mentions.

Russian state-owned media mentioned the OSCE Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) (143 mentions) most often when referencing external actors in the Donetsk civic space. While Russian coverage of the international watchdog was predominantly neutral, these observers received some negative attention from Russian state-owned media (8 negative mentions). This negative coverage was usually a result of OSCE reporting that Moscow perceived as favorable towards Ukraine. In general, Russian state media coverage was positive towards organizations that were critical of the Ukrainian government and negative towards organizations that supported Ukrainian authorities.

Figure 2. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Donetsk by Sentiment

Number of Mentions, January 2015 - March 2021

Mentions of foreign and intergovernmental civic actors involved in Donetsk were predominantly neutral (86 percent). Negative coverage (8 percent) was primarily oriented towards Ukrainian and Western actors—from foreign journalists filming Donetsk militias to Ukrainian activists enforcing a transport blockage on goods to Donbas—seen as hindering the “independence” of Donetsk from Ukraine. Positive coverage (6 percent) was largely directed towards Russian humanitarian groups, such as the Fair Aid Charity Fund (6 positive mentions).

2.6 Russian State Media’s Focus on Donetsk’s Civic Space over Time

For many of the occupied territories, Russian state media mentions spike around major events and tend to show up in clusters. This remains true in Donetsk, as spikes appear during key events, such as journalist deaths in the War in Donbas, as well as the self-declared DPR “elections” in November 2018. The biggest spike occurred during a flare-up in attacks on journalists during the war in August 2015.

Figure 3. Russian State Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors in Donetsk

Number of Mentions Recorded

Russian state media focused on civic space events that criticized Ukrainian authorities or supported Donetsk’s “independence”. In particular, Russian state media sought to portray Ukraine as an oppressor in the War in Donbas, Russia as coming to the aid of an oppressed group, and those that opposed the war as complicit in supporting Ukrainian atrocities. Russian state-run media highlighted journalist deaths and attacks near foreign observers in order to dehumanize Ukrainian authorities and mobilize support for the Donbas during the war. It painted Moscow as the responsible actor, promoting the protection of journalists whose safety was compromised by Ukrainian restriction.

3. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions of Civic Space in Donetsk

Restrictions on civic space actors can take various forms. We focus on three common ways to effectively deter or penalize civic participation: (i) harassment or violence initiated by state or non-state actors; (ii) proposal or passage of restrictive “legislation” or executive branch policies; and (iii) legal action brought by de facto authorities against civic actors.

In this section, we examine the restrictions faced by civic space actors over time, the initiators, and targets (section 3.1); and the specific nature and types of restrictions of civic space actors throughout the period (section 3.2). Donetsk civic space actors experienced 20 known restrictions between January 2017 and March 2021 (Figure 4). The period of review (January 2015 to March 2021 for other indicators) was truncated for these indicators, due to the volume of coverage. These restrictions were heavily weighted towards instances of harassment or violence (80 percent). There were fewer instances of legal action brought by de facto authorities (15 percent) or newly proposed or implemented restrictive “legislation” (5 percent); however, these instances can have a multiplier effect in creating a legal mandate to pursue other forms of restriction. [22]

Figure 4. Recorded Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Donetsk

Number of Instances

3.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time

Instances of restriction occurred every year across this time period with a small spike in 2017 (Figure 4). Other community groups were most frequently the targets of restriction (Figure 5), accounting for nearly half (44 percent) of the instances of violence and the only civic space actors targeted through restrictive “legislation” (100 percent of instances).

Figure 5. Recorded Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Donetsk by Targeted Group

Number of Instances, January 2017 - March 2021

Figure 6 breaks down the targets of restrictions by political ideology or affiliation in the following categories: pro-democracy, pro-Western, and anti-Kremlin. [23] Pro-democracy organizations and activists were mentioned 4 times as targets of restriction during this period. [24] Pro-Western organizations and activists were mentioned 8 times as targets of restrictions . [25] Anti-Kremlin organizations and activists were mentioned 5 times as targets of restriction . [26]

Figure 6. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Donetsk by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2017 - March 2021

The self-declared government of the DPR was the most prolific initiator of harassment or violence, with 63 percent of mentions. The initiators of legal action were always de facto authorities, either directly or by association (e.g., the spouse or immediate family member).

The Russian state-owned media outlet Rossiya 24 and the Ukrainian Armed Forces both initiated instances of violence or harassment in Donetsk during the period. However, unknown (i.e., unidentified) actors committed the next highest number of instances of harassment or violence (4 instances), including acts of vandalism against religious groups and attacks on local activists.

Figure 7. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Donetsk by Initiator

Number of Instances Recorded

3.2 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

There were 10 instances of harassment (all acted-upon) and 6 instances of violence (all acted-upon) against civic space actors recorded between 2017 and 2021. Since this data is collected on the basis of reported incidents, this data likely understates threats which are less visible (see Figure 8). The most frequent type of harassment included seizing and closing religious places of worship (5 instances).

Six instances of acted-on violence towards civic space actors were recorded in Donetsk. In one instance in June 2020, local Donetsk activist Valentina Buchok was attacked in her garden, when a hand grenade tripwire set up for her was detonated. This was not the first attack against her, as a similar explosive was found outside her house in October 2019. [27]

Figure 8. Acted-On Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Donetsk

Number of Instances Recorded

There was only one instance of restrictive “legislation” (1) in Donetsk, but it is important to capture, as it gives the de facto authorities a mandate to constrain civic space with long-term cascading effects. This indicator is limited to a subset of “laws”, “decrees”, or other formal policies and rules that may have a deleterious effect on civic space actors, either subgroups or in general. Both proposed and passed restrictions qualify for inclusion, but we focus exclusively on new and negative developments in laws or rules affecting civic space actors. We exclude discussion of pre-existing laws and rules or those that constitute an improvement for civic space.

Jehovah’s Witnesses, tagged as “Other community groups” in the data, was the primary target of restrictive “legislation”. The law intentionally banned the religious group from practicing and organizing in Donetsk. In September 2017, the Donetsk Supreme Court banned the practicing of the religion outright. [28]

Donetsk had 3 recorded instances of legal action brought by de facto authorities between January 2017 and March 2021. In May 2017, Donetsk de facto authorities detained Professor Ihor Kozlovsky for possession of a weapon, though this is likely an indirect nuisance charge for his pro-Ukrainian stances—a tactic often used by regimes elsewhere in the region to discredit anti-government activists. [29] The self-declared &ldquogovernment of Donetsk” also brought a case against journalist Stanyslav Aseyev in June 2017, after he exposed human rights violations committed by the “Donetsk authorities”. [30] Lastly, activist Dmitry Batrak was charged with espionage after sharing information about the position of Donetsk militias with the Ukrainian military. [31] The charges in the Aseyev and Batrak cases were directly tied to fundamental freedoms (e.g., freedom of speech, freedom of assembly), while Kozlovsky’s case was not.

4. Conclusion

In this supplemental profile, we demonstrate that the Kremlin uses multiple channels—financial and in-kind support, as well as state-backed media—to influence Donetsk civic space actors. The Russian government appears to orient its activities to promote two narratives which advance its interests.

First, the Kremlin focuses on supporting Donetsk’s “independence” from Ukraine by fostering a distinct civic space identity in the occupied territory. Russian state-owned media cited domestic Donetsk journalists and media outlets, such as the Donetsk News Agency, to bolster the credibility of these outlets. Kremlin-backed institutions funded training for Donetsk labor unions, further strengthening an independent civic space.

Second, the Kremlin criticizes Ukrainian or pro-Ukrainian organizations in Donetsk, discrediting officials and driving a wedge between the Ukrainian and Donetsk civil societies. Russian state-owned media assigned positive coverage to anti-Ukrainian protesters and highlighted journalists killed in the war, blaming Ukraine for the War in Donbas. At the encouragement of Moscow, the de facto authorities of the self-declared DPR detained pro-Ukrainian activists and journalists, accusing them of espionage. These acts are intended to villainize the Ukrainian authorities and discredit the actions of Kyiv in Donetsk.

As highlighted by the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin leverages occupied territories as a tool for expanding its control. By discrediting Ukrainian organizations and bolstering civic space organizations in Donetsk independent of Ukraine, the Kremlin paved the way for first the creation of the so-called Donetsk People's Republic and later the illegal annexation of the self-declared DPR by Russia.

Civic Space Report Occupied Territories Supplement

De Facto Luhansk People’s Republic

Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence

Emily Dumont and Lincoln Zaleski

April 2023

Executive Summary

As a companion to AidData’s main Ukraine Country Report, this supplemental profile surfaces insights about the health of civic space and vulnerability to malign foreign influence specific to the self-declared Luhansk People’s Republic. The analysis was part of a broader three-year initiative by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to produce quantifiable indicators to monitor civic space resilience in the face of Kremlin influence operations over time (2010 to 2021) and across 17 countries of Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E), including 7 territories that are occupied or autonomous and vulnerable to malign actors.

Below we summarize the top-line findings from our indicators on the channels of Russian malign influence operations as well as the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Luhansk:

- Russian-backed Civic Space Projects: The Russian government channeled financing and in-kind support to two Luhansk recipient organizations via two civic space-relevant projects between January 2015 and September 2020. The projects emphasized funding anti-Ukraine propaganda and delivering humanitarian aid. Russian state overtures were primarily oriented towards the “capital” of Luhansk. The Kremlin supported groups that furthered Luhansk’s separation from Ukraine.

- Russian State-run Media: The Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News referenced Luhansk civic space actors 668 times between January 2015 and March 2021; however, more than half of these mentions were focused on intergovernmental organizations or Russian civil society actors operating in Luhansk. Media organizations were the most frequently mentioned, followed by other community organizations. The overall tone of mentions was largely neutral. Russian state media often reinforced the messaging of the self-declared Luhansk regional government, particularly with regard to negative mentions of opposition protesters.

- Restrictions of Civic Actors: Luhansk civic space actors were the targets of 25 known restrictions between January 2017 and March 2021. Eighty-four percent of these restrictions involved harassment or violence, followed by newly proposed or implemented restrictive “legislation” (8 percent), and legal action brought by de facto authorities (8 percent). Other community groups, especially religious organizations, were the targets in the majority (80 percent) of cases. The preponderance of harassment or violence was initiated by the de facto authorities of Russian-occupied Luhansk.

A Note on Vocabulary

The authors recognize the challenge of writing about contexts with ongoing hot and/or frozen conflicts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consistently label groups of people and places for the sake of data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that terminology is political, but our use of terms should not be construed to mean support for one faction over another. For example, when we talk about self-declared Luhansk People’s Republic, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the Ukrainian government in Kyiv; or when we analyze the de facto authorities’ legislation or legal action to restrict civic action, it is not to grant legitimacy to the laws or courts of separatists, but rather to glean meaningful insights about the ways in which institutions are co-opted or employed to constrain civic freedoms.

Acknowledgements

This supplemental profile was prepared by Emily Dumont and Lincoln Zaleski. John Custer, Sariah Harmer, Parker Kim, and Sarina Patterson contributed editing, formatting, and supporting visuals. We are grateful for Ania Leska’s contribution of fact-checking and editing. We acknowledge the assistance of Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Kelsey Marshall, and our research assistants for their invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report: Jacob Barth, Kevin Bloodworth, Callie Booth, Catherine Brady, Temujin Bullock, Lucy Clement, Jeffrey Crittenden, Emma Freiling, Cassidy Grayson, Annabelle Guberman, Sariah Harmer, Hayley Hubbard, Hanna Kendrick, Kate Kliment, Deborah Kornblut, Aleksander Kuzmenchuk, Amelia Larson, Mallory Milestone, Alyssa Nekritz, Megan O’Connor, Tarra Olfat, Olivia Olson, Caroline Prout, Hannah Ray, Georgiana Reece, Patrick Schroeder, Samuel Specht, Andrew Tanner, Brianna Vetter, Kathryn Webb, Katrine Westgaard, Emma Williams, and Rachel Zaslavsk. The findings and conclusions of this supplement are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

Citation

Dumont, E., Zaleski, L. (2023). Luhansk People's Republic: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence in the lead up to war. Occupied Territories Supplemental Profile. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary.

1. Introduction

The Kremlin established a breakaway “government” in Luhansk, following its occupation by Russia, as a tactic to weaken perceived adversaries and further its influence in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. [32] The Kremlin appears to have two overarching goals for its overtures in Luhansk: foster a Luhansk civic space independent of Ukraine and discredit Ukrainian organizations in Luhansk.

As a companion to AidData’s main Ukraine Country Report, this supplemental profile examines the Kremlin’s tools of influence in Luhansk’s civic space [33] which seek to manipulate local attitudes in support of two key narratives. First, the Russian government focuses on supporting Luhansk’s “independence” from Ukraine by fostering a distinct identity for Luhansk via media outlets, labor unions, and other civil society organizations. Second, the Kremlin criticizes Ukrainian or pro-Ukrainian organizations in Luhansk, discrediting officials and driving a wedge between the Ukrainian and Luhansk civil societies.

This profile is part of a broader three-year research effort conducted by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to collect and analyze vast amounts of historical data on civic space and Russian influence across 17 countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E), including 7 territories that are occupied or autonomous and vulnerable to malign actors. For the purpose of this project, we define civic space as: the formal laws, informal norms, and societal attitudes which enable individuals and organizations to assemble peacefully, express their views, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction.

In the remainder of this supplemental profile, we provide additional details on how the Russian government uses its state institutions to influence the Luhansk population in support of these narratives. In section 2, we examine Russian projectized support relevant to civic space and analyze Russian state-backed media mentions of civic space actors. In section 3, we enumerate restrictions of civic space actors. A methodology document is available via aiddata.org.

Table 1. Quantifying External Influence on and Restrictions of Luhansk’s Civic Space

|

Civic Space Barometer |

Supporting Indicators |

|

Russian state financing and in-kind projectized support relevant to civic space actors or regulators (January 2015-September 2020) |

|

|

Russian state media mentions of civic space actors or democratic rhetoric (January 2015-March 2021) |

|

|

Restrictions of civic space actors (January 2017-March 2021) |

|

Notes: Table of indicators collected by AidData to assess the health of Luhansk’s domestic civic space and vulnerability to Russian influence. Indicators are categorized by barometer (i.e., dimension of interest) and specify the time period covered by the data in the subsequent analysis.

2. External Channels of Influence: Kremlin Civic Space Projects and Russian State-Run Media in Luhansk

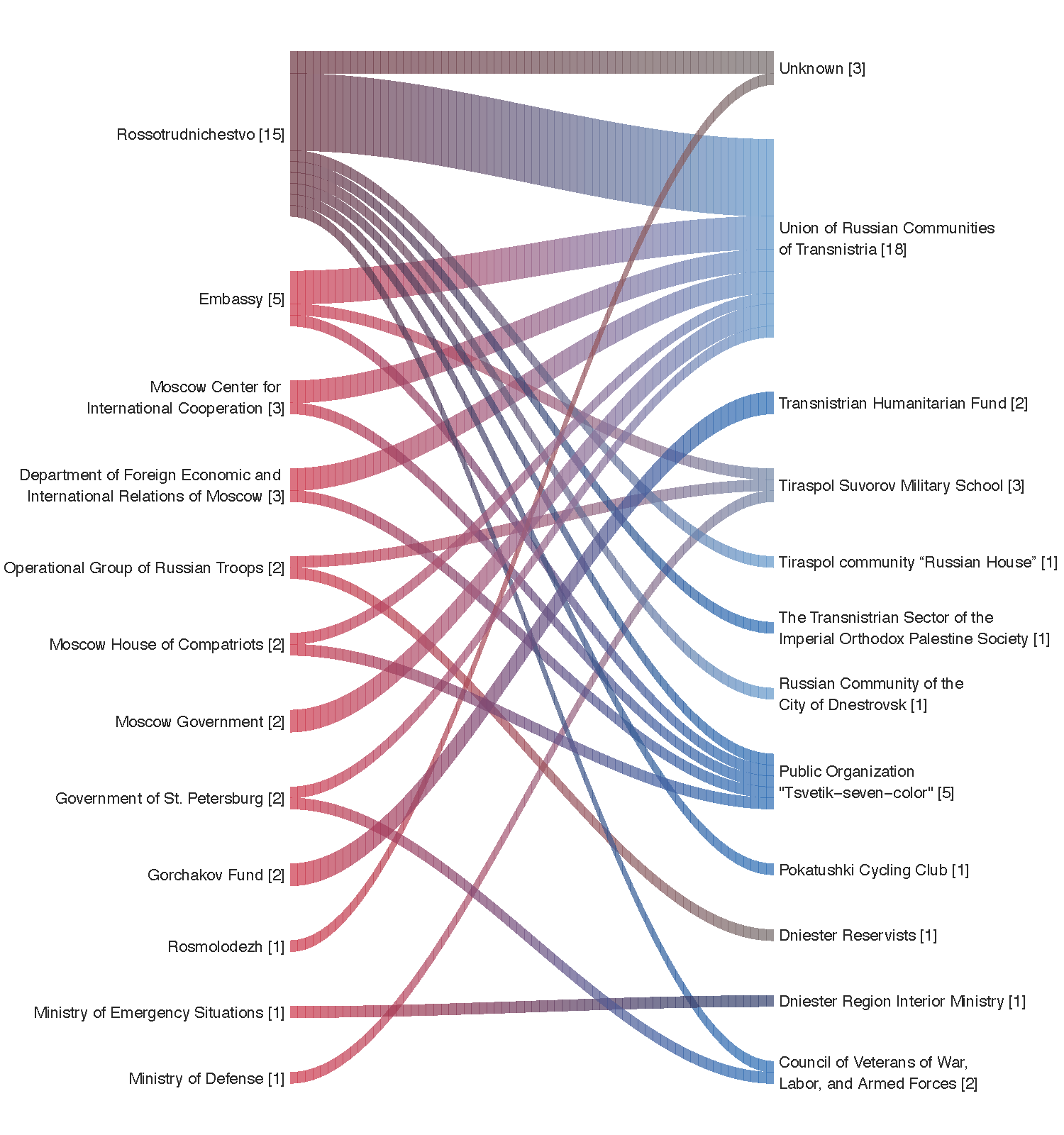

In this project, we tracked financing and in-kind support from Kremlin-affiliated agencies to: (i) build the capacity of those that “regulate” the activities of civic space actors; and (ii) co-opt the activities of civil society actors within E&E countries in ways that seek to promote or legitimize Russian policies abroad. The Kremlin supported 2 known Luhansk civic organizations via 2 civic space-relevant projects during the period of January 2015 to September 2020 . Kremlin-backed projects in 2016 and 2017 emphasized financing militant groups to promote anti-Ukraine propaganda and facilitating humanitarian aid. In section 2, we unpack more specifics on the suppliers (section 2.1), recipients (section 2.2), and focus of Russian state-backed support to the Luhansk civic space (section 2.3).

Since E&E countries are exposed to a high concentration of Russian state-run media, we analyzed how the Kremlin may use its coverage to influence public attitudes about civic space actors (formal organizations and informal groups), as well as public discourse pertaining to democratic norms or rivals in the eyes of citizens. Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced Luhansk civic actors a total of 668 times from January 2015 to March 2021. The vast majority of these mentions (485 instances) were of non-Luhansk and intergovernmental actors, while the remaining portion (183 instances) consisted of mentions of domestic Luhansk civic space actors. Russian state media covered a diverse set of civic actors, mentioning 40 organizations by name, as well as 26 informal groups operating in the Luhansk civic space. We examine Russian state media coverage of domestic (section 2.4) and external (section 2.5) actors in Luhansk’s civic space, and how this has evolved over time (section 2.6).

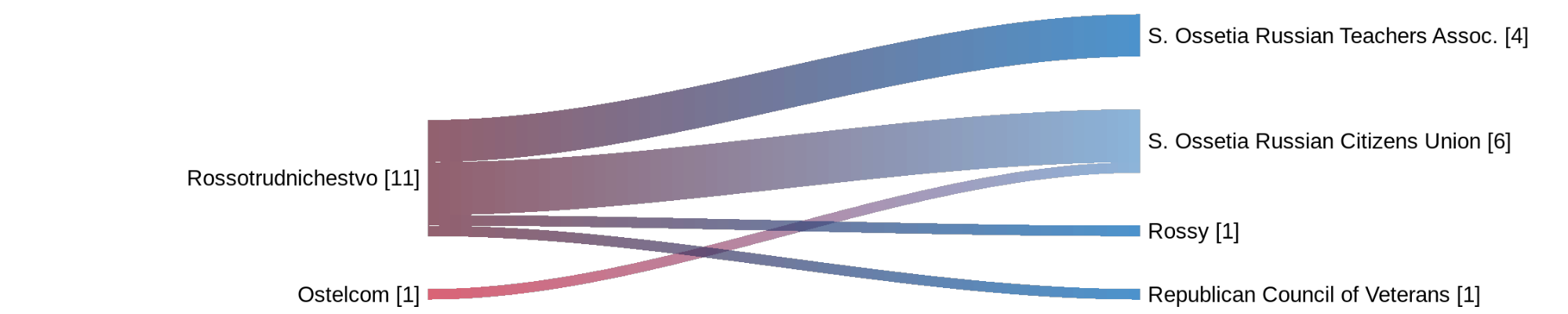

2.1 The Suppliers of Russian State-Backed Support to Luhansk’s Civic Space

The Kremlin routed its engagement in Luhansk through 2 different channels: the Fund for Support of International Humanitarian Projects and the Ministry of Emergency Situations. The stated missions of these Russian government entities focus on defense and humanitarian aid. Civil society development was more often a supporting theme than the primary purpose of most of these entities' missions.

The Russian Ministry of Emergency Situations [34] is a Russian government agency with a mandate to protect citizens and territories from both natural and man-made emergencies. In one project, the Russian ministry assisted a Spanish humanitarian organization working in the region with the delivery of cargo including food, hygiene items, clothing, and other aid supplies to Luhansk. Using a Russian government agency to deliver humanitarian supplies further promotes the Kremlin’s desired narrative for itself as delivering tangible benefits to the local population.

The Fund for Support of International Humanitarian Projects was set up by Moscow-based International Payment Bank to channel funds to the self-declared Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR) “State” Bank. Headed by Vladimir Pashkov, who has ties to both the Russian government, as well as the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic and the self-declared LPR, these funds are believed to have funded anti-Ukrainian propaganda and ameliorated a budget deficit among pro-Russian militant groups. This profile provides an initial baseline of Kremlin support to civic space actors in Luhansk but likely undercounts the full universe of such relationships.

2.2 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Luhansk’s Civic Space

Pro-Russian “military” groups affiliated with the self-declared LPR received financial support from the Kremlin to engage in anti-Ukraine propaganda activities and to ameliorate a budget deficit. The regional arm of Spanish-charitable organization Good Cause also received in-kind support to deliver humanitarian aid.

2.3 The Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Luhansk’s Civic Space

Russian support to civic space actors in Luhansk appears to be divided between non-financial support and direct transfers of funding. Of the two projects identified, only one explicitly described receiving grants. The other project received in-kind assistance in the form of distribution of humanitarian items. By supporting “military” groups and funding anti-Ukraine propaganda in Luhansk, the Kremlin stoked the seeds of discontent and promoted an independent Luhansk long before the current Russian military invasion of Ukraine. With its support to humanitarian aid organizations, the Kremlin also sought to position itself as delivering tangible benefits to the local population and diminishing Kyiv’s influence over the occupied territory. Additionally, a number of Russian projects fell outside of the parameters for inclusion in this report, meaning that Russian flows to Luhansk are likely undercounted.

2.4 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Luhansk Civic Space Actors

Three-quarters (75 percent) of Russian media mentions pertaining to domestic actors in Luhansk’s civic space referred to specific groups by name. The 11 named domestic actors represent a diverse cross-section of organizational types, ranging from political parties to civil society organizations to media outlets. The vast majority of named domestic actors mentioned were media organizations (129 mentions), followed by other community organizations (4 mentions). LuganskInformCenter, the official news agency for the Russian-occupied Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR), accounted for the high number of media mentions with Russian state media citing LuganskInformCenter as a domestic source 127 times.

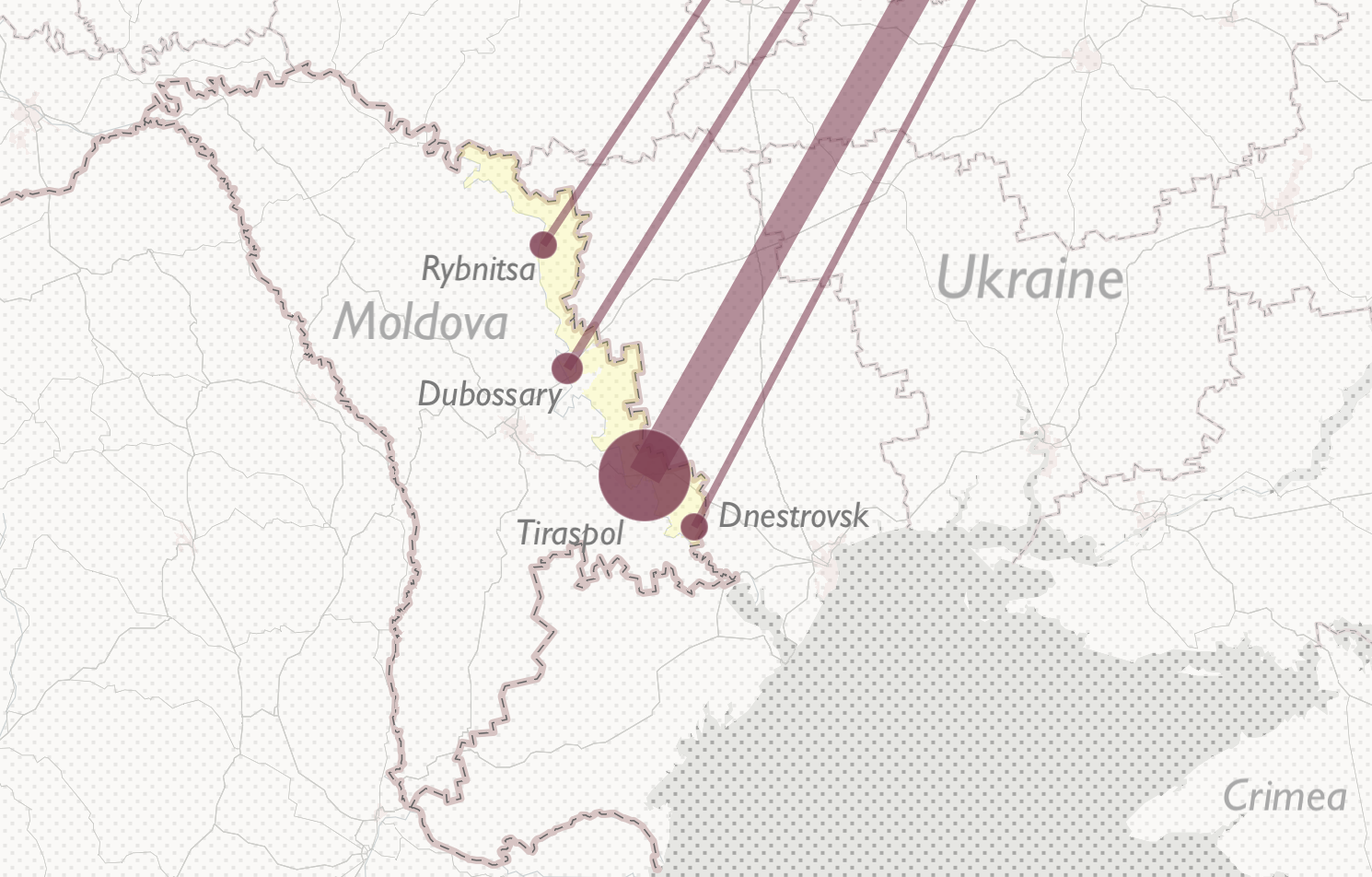

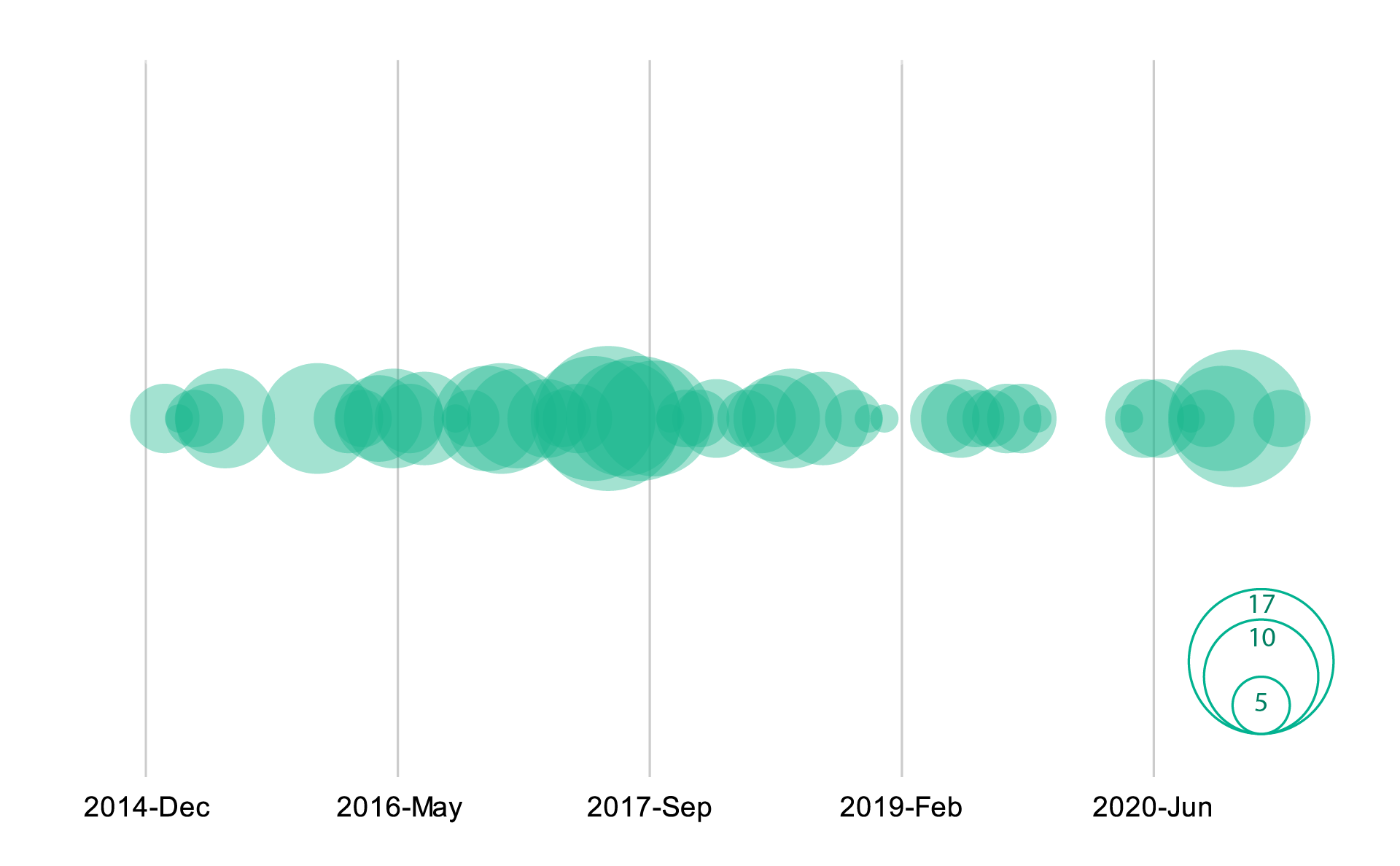

In our sample of Russian state media articles, mentions of specific Luhansk civic space actors were primarily neutral (97 percent) in tone. The Ukraine Salvation Committee (2 negative mentions) and the organization Aidar (1 negative mention), which supports Ukrainian independence, attracted more negative coverage. Comparatively, the activist group Immortal Regiment was accorded more positive coverage by Russian state-run media in relation to the organization of a WWII victory parade.