Civic Space Country Report

Ukraine: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence in the lead up to war

Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, Lincoln Zaleski

March 2023

Executive Summary

This report surfaces insights about the health of Ukraine’s civic space and vulnerability to malign foreign influence in the lead up to Russia’s February 2022 invasion. The analysis was part of a broader three-year initiative by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to produce quantifiable indicators to monitor civic space resilience in the face of Kremlin influence operations over time (from 2010 to 2021) and across 17 countries and 7 occupied or autonomous territories in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). Research included extensive original data collection to track Russian state-backed financing and in-kind assistance to civil society groups and regulators, media coverage targeting foreign publics in the region, and indicators to assess domestic attitudes to civic participation and restrictions of civic space actors.

Although Russia’s aggression has undeniably altered the civic space landscape in Ukraine for years to come, the insights from this profile are useful to: (i) illuminate how the Kremlin exploits hybrid tactics to deter resistance long in advance of conventional military action; and (ii) identify underlying points of resilience that enabled Ukraine to sustain a whole-of-society resistance to the Kremlin’s aggression. Below we summarize the top-line findings from our indicators on the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Ukraine, as well as channels of Russian malign influence operations:

- Restrictions of Civic Actors: Ukraine accounted for the fourth largest volume of restrictions (494 recorded instances) initiated against civic space actors in the E&E region, trailing Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan. The majority of restrictions of civic space activity documented between January 2017 and March 2021 were in the form of harassment or violence (85 percent), followed by state-backed legal cases (8 percent), as well as newly proposed or implemented restrictive legislation (7 percent). Forty percent of instances of violence or harassment throughout the entire period were carried out by separatist authorities in Russia-occupied Donetsk and Luhansk, or Russian occupiers in Crimea. Nine restrictions involved foreign governments, including Turkey (2), Azerbaijan (2), and Russia (5). The lion’s share of these restrictions occurred in just two years, 2017 and 2018, coinciding with the imposition of Russian law in Crimea and protests following the arrest of Mikheil Saakashvili. There was a marked downturn in restrictions against civic space actors documented between 2019 and 2021, coinciding with the election of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

- Attitudes Towards Civic Participation: Ukrainians were demonstrating, donating, volunteering, and helping strangers at much higher levels in 2021 than seen the decade prior, though interest in politics remained muted. In 2020, two-thirds of Ukrainians reported they were disinterested in politics and a mere quarter of the population had confidence in their government, political parties, and the parliament. This disenchantment with organized politics stands in sharp contrast with a substantial uptick in reported participation in other forms of civic life. Over 40 percent of Ukrainians said they had or would join a demonstration in 2020 (+26 percentage points since 2010) and reported higher levels of membership in nearly every voluntary organization type, with the largest gains among churches, art organizations, and self-help groups. In 2021, 47 percent of Ukrainians reported donating to charity, 24 percent volunteered with an organization, and over 75 percent reported helping a stranger—charting Ukraine’s highest civic engagement score in a decade.

- Russian-backed Civic Space Projects: The Russian government channeled financing and in-kind support via four Kremlin-affiliated agencies to seven Ukrainian and Crimean recipient organizations via five civic space-relevant projects between January 2015 and August 2021. Legislative and executive branch restrictions of Russian-backed organizations in Ukraine in the years prior to the invasion likely inhibited the Kremlin from relying as heavily on this channel of influence, relative to the volume of activity seen in other countries. Regardless, the thematic focus of the Kremlin’s support was consistent with elsewhere in the region: mobilize pro-Russian sympathizers, stoke discontent with Kyiv, and create a pretext for Russian intervention. Consistent with these aims, Kremlin support prioritized youth “patriotic” education, Eurasian integration, and increased autonomy for regional governments, particularly in the eastern oblasts. As documented in two profiles on the Russia-occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk, the Kremlin also backed additional pro-Russian groups in the Donbas.

- Russian State-run Media: Ukraine attracted 55 percent of all Russian state-run media outlets’ mentions across the E&E region related to specific civic space actors and five keywords of interest (NATO, U.S., EU, West, democracy). Between January 2015 and March 2021, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News referenced Ukrainian civic actors 5,993 times. Media organizations, nationalist paramilitary groups, and political parties were the most frequently mentioned domestic actors. Coverage by Russian state media highlighted far-right groups to stoke concerns of rising neo-Nazism; vilified ethnic Crimean Tatar organizations and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church as a threat to conservative values; and criticized Kyiv’s mistreatment of foreign journalists to discredit the Ukrainian government. These Kremlin mouthpieces were even more prolific with regard to democratic rhetoric, mentioning NATO, the U.S., the EU, the West or democracy 6,563 times during the same period, with coverage concentrated around significant events in Ukrainian civic life (the one-year anniversary of the Odessa Trade Union House fire, 2017 restrictions on Russian banks and social media sites, and the 2019 Ukrainian presidential elections) as well as broader international stories (Crimea sanctions, the 2018 Kerch Strait incident, EU and NATO membership prospects, and the U.S.-Ukrainian alliance) as vehicles to proliferate pro-Russian messages.

Table of Contents

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Ukraine

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Ukraine: Targets, Initiators, Trends Over Time

2.2 Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Ukraine

3.1 Suppliers of Russian State-Backed Support to Ukrainian Civic Space

3.2 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Ukraine’s Civic Space

3.3 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Ukraine's Civic Space

3.4 Russian Media Mentions Related to Civic Space Actors and Democratic Rhetoric

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

5.3 Russian Financing and In-kind Support to Civic Space Actors or Regulators

5.4 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors and Democratic Rhetoric

Figures and Tables

Table 1. Quantifying Ukrainian Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of Ukrainian Civic Space Actors

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Ukraine

Figure 2. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Ukraine by Initiator

Figure 3. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Ukraine

Figure 4. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Ukraine by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Figure 5. Threatened versus Acted-On Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Ukraine

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Ukraine

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Ukraine

Figure 7. Interest in Politics: Ukrainian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2020

Figure 8. Political Action: Ukrainian Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2011 and 2020

Figure 9. Political Action: Participation by Ukrainian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2020

Table 4. Ukrainian Citizens’ Membership in Voluntary Organizations by Type, 2011 and 2020

Table 5. Ukrainian Confidence in Key Institutions, 2011 and 2020

Figure 11. Civic Engagement Index: Ukraine versus Regional Peers

Figure 12. Russian Projects Supporting Civic Space Actors by Type

Figure 13. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Ukrainian Civic Space

Figure 14. Locations of Russian Support to Ukrainian Civic Space

Figure 15. Young Guards of Crimea in the Union Patriotic Camp in the Donbas, 2021

Table 6. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in Ukraine by Sentiment

Table 7. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Ukraine by Sentiment

Figure 16. Russian State Media Mentions of Ukrainian Civic Space Actors

Figure 17. Keyword Mentions by Russian State Media in Relation to Ukraine

Figure 18. Keyword Mentions versus Mentions of Ukrainian Civic Space Actors by Russian State Media

Figure 19. Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State Media in Relation to Ukraine

Table 8. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, and Lincoln Zaleski. John Custer, Sariah Harmer, Parker Kim, and Sarina Patterson contributed editing, formatting, and supporting visuals. Kelsey Marshall and our research assistants provided invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report including: Jacob Barth, Kevin Bloodworth, Callie Booth, Catherine Brady, Temujin Bullock, Lucy Clement, Jeffrey Crittenden, Emma Freiling, Cassidy Grayson, Annabelle Guberman, Sariah Harmer, Hayley Hubbard, Hanna Kendrick, Kate Kliment, Deborah Kornblut, Aleksander Kuzmenchuk, Amelia Larson, Mallory Milestone, Alyssa Nekritz, Megan O’Connor, Tarra Olfat, Olivia Olson, Caroline Prout, Hannah Ray, Georgiana Reece, Patrick Schroeder, Samuel Specht, Andrew Tanner, Brianna Vetter, Kathryn Webb, Katrine Westgaard, Emma Williams, and Rachel Zaslavsk. The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

This research was made possible with funding from USAID's Europe & Eurasia (E&E) Bureau via a USAID/DDI/ITR Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) cooperative agreement (AID-A-12-00096). The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

A Note on Vocabulary

The authors recognize the challenge of writing about contexts with ongoing hot and/or frozen conflicts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consistently label groups of people and places for the sake of data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that terminology is political, but our use of terms should not be construed to mean support for one faction over another. For example, when we talk about an occupied territory, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the Ukrainian government in Kyiv. Or, when we analyze the de facto authorities’ use of legislation or the courts to restrict civic action, it is not to grant legitimacy to the laws or courts of separatists, but rather to glean meaningful insights about the ways in which institutions are co-opted or employed to constrain civic freedoms.

Citation

Custer, S., Mathew, D., Burgess, B., Dumont, E., Zaleski, L. (2023). Ukraine: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence in the lead up to war . March 2023. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William and Mary.

1. Introduction

It is hard to imagine Vladimir Putin, on the cusp of invading Ukraine in February 2022, viewing his odds of success as anything other than inevitable. Yet, more than one year later, the Kremlin’s victory is anything but certain. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that the Kremlin severely underestimated the bravery and resilience of the Ukrainian people. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy was an important part of this story, but the willingness of the average Ukrainian citizen to mount a whole-of-society resistance to Putin’s aggression also played a decisive role in overcoming the odds. As we show in this country report, the seeds of this solidarity began much earlier, with Russia’s 2022 invasion only adding fuel to the fire of an increasingly energized Ukrainian citizenry.

There is a broader lesson here that reverberates far beyond Ukraine: investing early in a robust civil society is not just an optional “extra” but fundamental to a society’s ability to deter, withstand, and repel the destructive intent of an external aggressor in times of peace and war. It is therefore critical for policymakers and practitioners to have better information at their fingertips to monitor the relative health of civil society across countries and over time, reinforce sources of societal resilience, and mitigate risks in the face of autocratizing governments at home and malign influence from abroad.

Over the last three years, AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—has collected and analyzed vast amounts of historical data on civic space and Russian influence across 17 countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). [1] In this country report, we present top-line findings specific to Ukraine from a novel dataset which monitors four barometers of civic space in the E&E region from 2010 to 2021 (see Table 1). [2] For the purpose of this project, we define civic space as: the formal laws, informal norms, and societal attitudes which enable individuals and organizations to assemble peacefully, express their views, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. [3] Here we provide only a brief introduction to the indicators monitored in this and other country reports. However, a more extensive methodology document is available via aiddata.org which includes greater detail about how we conceptualized civic space and operationalized the collection of indicators by country and year.

Civic space is a dynamic rather than static concept. The ability of individuals and organizations to assemble, speak, and act is vulnerable to changes in the formal laws, informal norms, and broader societal attitudes that can facilitate an opening or closing of the practical space in which they have to maneuver. To assess the enabling environment for Ukrainian civic space, we examined two indicators: restrictions of civic space actors (section 2.1) and citizen attitudes towards civic space (section 2.2). Because the health of civic space is not strictly a function of domestic dynamics alone, we also examined two channels by which the Kremlin could exert external influence to dilute democratic norms or otherwise skew civic space throughout the E&E region. These channels are Russian state-backed financing and in-kind support to government regulators or pro-Kremlin civic space actors (section 3.1) and Russian state-run media mentions related to civic space actors or democracy (section 3.2).

Since restrictions can take various forms, we focus here on three common channels which can effectively deter or penalize civic participation: (i) harassment or violence initiated by state or non-state actors; (ii) the proposal or passage of restrictive legislation or executive branch policies; and (iii) state-backed legal cases brought against civic actors. Citizen attitudes towards political and apolitical forms of participation provide another important barometer of the practical room that people feel they have to engage in collective action related to common causes and interests or express views publicly. In this research, we monitored responses to citizen surveys related to: (i) interest in politics; (ii) past participation and future openness to political action (e.g., petitions, boycotts, strikes, protests); (iii) trust or confidence in public institutions; (iv) membership in voluntary organizations; and (v) past participation in less political forms of civic action (e.g., donating, volunteering, helping strangers).

In this project, we also tracked financing and in-kind support from Kremlin-affiliated agencies to: (i) build the capacity of those that regulate the activities of civic space actors (e.g., government entities at national or local levels, as well as in occupied or autonomous territories ); and (ii) co-opt the activities of civil society actors within E&E countries in ways that seek to promote or legitimize Russian policies abroad. Since E&E countries are exposed to a high concentration of Russian state-run media, we analyzed how the Kremlin may use its coverage to influence public attitudes about civic space actors (formal organizations and informal groups), as well as public discourse pertaining to democratic norms or rivals in the eyes of citizens.

Although Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022 undeniably altered the civic space landscape in Ukraine for years to come, the historical information in this report is still useful in three respects. By taking the long view, this report sheds light on the Kremlin’s patient investment in hybrid tactics to foment unrest, co-opt narratives, demonize opponents, and cultivate sympathizers in target populations as a pretext or enabler for military action. Second, by examining both domestic and external factors in tandem, this report provides new appreciation for underlying points of vulnerability and resilience that serve as the foundation for Ukraine’s ability to mount and sustain a whole-of-society resistance to the Kremlin’s aggression. Third, the comparative aspect of these indicators lends itself to drawing lessons learned about bolstering resilience to malign foreign influence with relevance for other E&E countries.

Table 1. Quantifying Ukrainian Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

|

Civic Space Barometer |

Supporting Indicators |

|

Restrictions of civic space actors (January 2017–March 2021) |

|

|

Citizen attitudes toward civic participation space (2010–2021)

|

|

|

Russian state financing and in-kind support to civic space actors or regulators (January 2015–August 2021) |

|

|

Russian state media mentions of civic space actors or democratic rhetoric (January 2015–March 2021) |

|

Notes: Table of indicators collected by AidData to assess the health of Ukraine’s domestic civic space and vulnerability to Russian influence. Indicators are categorized by barometer (i.e., dimension of interest) and specify the time period covered in the subsequent analysis.

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Ukraine

A healthy civic space is one in which individuals and groups can assemble peacefully, express views and opinions, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. Laws, rules, and policies are critical to this space, in terms of rights on the books (de jure) and how these rights are safeguarded in practice (de facto). Informal norms and societal attitudes are also important, as countries with a deep cultural tradition that emphasizes civic participation can embolden civil society actors to operate even absent explicit legal protections. Finally, the ability of civil society actors to engage in activities without fear of retribution (e.g., loss of personal freedom, organizational position, and public status) or restriction (e.g ., constraints on their ability to organize, resource, and operate) is critical to the practical room they have to conduct their activities. If fear of retribution and the likelihood of restriction are high, this likely has a chilling effect on the motivation of citizens to form and participate in civic groups.

In this section, we assess the health of civic space in Ukraine over time in two respects: the volume and nature of restrictions against civic space actors (section 2.1) and the degree to which Ukrainians engage in a range of political and apolitical forms of civic life (section 2.2). Ukraine accounted for the fourth largest volume of restrictions initiated against civic space actors in the E&E region during the reporting period, driven by high instances of harassment or violence in 2017 and 2018. [4] There was a marked downturn in such restrictions of civic space actors between 2019 and 2021, coinciding with the election of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. In parallel, Ukrainians were demonstrating, donating, volunteering, and helping strangers at higher levels in 2021 than seen the decade prior. We delve into greater detail about these trends and other developments in Ukraine’s domestic civic space in the remainder of this section.

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Ukraine: Targets, Initiators, Trends Over Time

Between January 2017 and March 2021, we documented 494 known restrictions of Ukrainian civic space actors (Table 2), most frequently instances of harassment or violence (85 percent). There were fewer instances of state-backed legal cases (8 percent) and newly proposed or implemented restrictive legislation (7 percent); however, these instances can have a multiplier effect in creating a legal mandate for a government to pursue other forms of restriction.

The volume of these restrictions were unevenly distributed and decreased over the time period, particularly following the April 2019 election of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy (Figure 1). Thirty-seven percent of cases were recorded in 2017 alone, coinciding with two key events—the imposition of a Russian law in Crimea that restricted “missionary activity” in April 2017, and the arrest of Mikheil Saakashvili and ensuing protests. These imperfect estimates are based upon publicly available information either reported by the targets of restrictions, documented by a third-party actor, or covered in the news (see Section 3). [5]

Table 2.Recorded Restrictions of Ukrainian Civic Space Actors

|

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021–Q1 |

Total |

|

Harassment/Violence, excluding Crimea & Donbas |

80 |

80 |

43 |

38 |

7 |

248 |

|

Harassment/Violence in Crimea |

59 |

32 |

20 |

11 |

3 |

125 |

|

Harassment/Violence in Donbas [6] |

19 |

17 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

45 |

|

Restrictive Legislation |

12 |

9 |

6 |

6 |

1 |

34 |

|

State-Backed Legal Cases |

14 |

11 |

3 |

10 |

4 |

42 |

|

Total |

184 |

149 |

77 |

66 |

18 |

494 |

Notes: Table of the number of restrictions initiated against civic space actors in Ukraine, disaggregated by type and year. Since the legitimacy of de facto authorities in Crimea and the Donbas are contested, we have categorized all instances of restriction (including restrictive legislation and legal cases) in the occupied territories as “harassment/violence.” Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Ukraine and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Ukraine

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment / Violence

Restrictive Legislation

State-Backed Legal Cases

Key Events Relevant to Civic Space in Ukraine

|

January 2017 |

Ukrainian government forces and pro-Russian separatist rebels, fighting in eastern Ukraine, accuse each other of disrupting a fragile truce declared in December. |

|

April 2017 |

Imposing Russian law in Crimea, the Prosecutor's Office only allows religious organizations registered with the authorities to perform missionary activities. |

|

July 2017 |

The EU ratifies Ukraine's association agreement, set to begin September 1. |

|

May 2018 |

Vladimir Putin opens a bridge linking southern Russia to Crimea, an action Ukraine calls illegal. |

|

November 2018 |

Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko declares martial law after Russia seizes three of Kyiv's navy vessels near the Kerch Strait. |

|

January 2019 |

With support from the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, Ukraine sets up its own Orthodox Church, breaking ties with Russian ecclesiastical supervision. |

|

April 2019 |

Volodymyr Zelenskyy, a television comedian and political novice, wins a presidential runoff with more than 70 percent of the vote, defeating Poroshenko. |

|

July 2019 |

The Servant of the People Party wins Parliamentary elections, marking the first time that the President's party has a majority in Ukrainian parliament. |

|

March 2020 |

Former businessman Denys Shmyhal is appointed Prime Minister with a mandate to stimulate industrial revival and improve tax receipts. |

|

June 2020 |

NATO recognizes Ukraine as an Enhanced Opportunities Partner. |

|

September 2020 |

The Russian Federation holds "elections" in the occupied territories of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol. |

|

February 2021 |

Zelenskyy orders sanctions against oligarchs, notably Viktor Medvedchuk, chairman of Ukraine’s largest pro-Russia political party and a close friend of Putin. |

The above charts visualize instances of civic space restrictions in Ukraine, including in Crimea and the Donbas, disaggregated by quarter and accompanied by a timeline of events in the political and civic space of Ukraine. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Ukraine and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Over one in every three instances (40 percent) of violence or harassment was carried out by separatist authorities in Russia-occupied Donetsk and Luhansk, or by the Russian occupying authorities in Crimea against the Crimean Tatars or a church. The Ukrainian government was the second-most prolific initiator of restrictions of civic space actors, accounting for 157 recorded mentions (Figure 2). Members of community groups—including the Crimean Tatar Mejlis, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and other churches in Russia-occupied Crimea—were frequent targets of restrictions (Figure 3). Domestic non-governmental actors were identified as initiators in 48 restrictions and there were some incidents involving unidentified assailants (53 mentions). Due to how the indicator was defined, the initiators of state-backed legal cases are either explicitly government agencies and government officials or those clearly associated with these actors (e.g., the spouse or immediate family member of a sitting official).

Of the nine instances of restriction which involved a foreign government, two were associated with Turkey, two with Azerbaijan, and five with Russia.

- Following the failed coup in Turkey in 2016, Yusuf Inan, a Turkish blogger, was accused of “trying to discredit some political figures and state officials in Turkey by carrying out a perception operation on social media.” [7] He was detained by the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU) in July 2018. In October 2019, a woman was attacked by Turkish Embassy staff in Kyiv, as she protested Turkish military action in Syria, outside their compound.

- Two incidents involving Azerbaijan pertained to the arrest and extended detention of Fikret Huseynli, a Dutch journalist of Azerbaijani origin. He was arrested at Boryspil International Airport near Kyiv in October 2017, based on an Interpol alert issued by Azerbaijan’s government.

- Among the instances that involved the Russian government, three were cases being investigated by, and tried in, Russian courts against Ukrainian citizens. The fourth instance was the September 2019 extradition request against Amkhad Ilayev, a Russian citizen seeking political asylum in Ukraine. The most violent among these instances was the assassination of Denis Voronekov, a former Russian lawmaker who defected to Ukraine and aired damning criticism of Russia's leadership. He was gunned down in broad daylight in the heart of Kyiv in 2017.

Figure 4 breaks down the targets of restrictions by political ideology or affiliation in the following categories: pro-democracy, pro-Western, and anti-Kremlin. [8] Pro-democracy organizations and activists were mentioned 87 times as targets of restriction during this period. [9] Pro-Western organizations and activists were mentioned 75 times as targets of restrictions. [10] There were also 162 instances where we identified the target organizations or individuals to be explicitly anti-Kremlin in their public views. [11] It should be noted that this classification does not imply that these groups were targeted because of their political ideology or affiliation, merely that they met certain predefined characteristics. In fact, these tags were deliberately defined narrowly such that they focus on only a limited set of attributes about the organizations and individuals in question.

Figure 2. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Ukraine by Initiator

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment/Violence

Notes: The figure visualizes recorded instances of harassment/violence of civic space actors in Ukraine, including in Crimea and the Donbas, categorized by initiator. If an instance of violence or harassment targeted multiple groups, it is counted for each group. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Ukraine and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Figure 3. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Ukraine

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2017 - March 2021

Notes: This figure shows the number of instances of harassment/violence of civic space actors in Ukraine, as well as in Crimea and the Donbas, disaggregated by the group targeted. If an instance of violence or harassment targeted multiple groups, it is counted for each group. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Ukraine and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Figure 4. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Ukraine by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment / Violence

State-Backed Legal Cases

Notes: These figures visualizes instances of harassment/violence and restrictive legislation initiated against civic space actors in Ukraine, including in Crimea and the Donbas, categorized by whether targets were known to be “pro-democracy,” “pro-Western,” or “anti-Kremlin,” as manually tagged by AidData staff. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Ukraine and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants .

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

Instances of harassment (6 threatened, 299 acted upon) of civic space actors were more common than episodes of outright physical harm (9 threatened, 104 acted upon) during the period. The vast majority of these instances (96 percent) were acted on, rather than merely threatened. However, since this data is collected on the basis of reported incidents, this likely understates threats which are less visible (see Figure 5). Of the 418 instances of harassment and violence, acted-on harassment accounted for the largest percentage (71 percent).

Figure 5. Threatened versus Acted-On Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Ukraine

Number of Instances Recorded

Notes: This figure visualizes instances of harassment/violence against civic space actors in Ukraine, including in Crimea and the Donbas. For definitions, please refer to the associated methodology document. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Ukraine and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Recorded instances of restrictive legislation in Ukraine (34) are important to capture, as they give government actors a mandate to constrain civic space with long-term cascading effects. This indicator is limited to a subset of parliamentary laws, chief executive decrees, or other formal executive branch policies and rules that may have a deleterious effect on civic space actors (either subgroups or in general). Both proposed and passed restrictions qualify for inclusion, but we focus exclusively on new and negative developments in laws or rules affecting civic space actors. We exclude discussion of pre-existing laws and rules or those that constitute an improvement for civic space.

Taking a closer look at instances of restrictive legislation, the Ukrainian government constrained civic space in three respects: (i) the media; (ii) the Church; and (iii) the Russian language. Ukraine’s legislative practices in the realm of civic space highlight the trade-offs that government leaders sometimes face in balancing competing priorities, such as protecting citizens from the Kremlin’s malign foreign influence operations on the one hand, while still preserving space for citizens to exercise their basic rights to assemble peacefully, express their views, and take collective action without fear. On the surface, one could read these examples of restrictive legislation as an effort to strengthen Ukraine’s resilience in the face of Russian hybrid warfare tactics or circumscribe civic space for the public good. [12]

Yet, these same laws applied indiscriminately can deter opposition or stoke discontent among populations that self-identify on the basis of shared language, culture, or religious ties. In fact, several of the examples below raised concern among domestic civil society and international watchdogs for these very reasons. As discussed in Section 3, it appears likely that the Kremlin did indeed exploit unease and disenfranchisement to some of these pieces of legislation as an entry point for influence in Ukraine.

Media restrictions: Decrees on cybersecurity and information security were introduced in Ukraine in February 2017, calling for legal mechanisms to block, monitor, and remove content deemed threatening to the state. This was followed by at least nine identified instances of drafting, reviewing or passing laws that imposed strict sanctions on the media. In June 2018, the Committee on Security and Defense approved a bill that would allow the government to block any website for 48 hours without court authorization. In January 2020, the Ukrainian Disinformation Bill gave the state the mandate to impose large penalties (from sizable fines to seven years imprisonment) for spreading false information. Activists expressed concern over the breadth and ambiguity of these laws which allow the authorities to determine what constitutes a threat or disinformation, such that the laws could be used to selectively harass government critics.

Religious restrictions: Although the Orthodox Church in Ukraine officially separated from the authority of the Moscow Patriarchate, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko signed a law in December 2018 obliging the Church to state in its title that it is subordinate to Russia. [13] In January 2019, the Ukrainian parliament passed a bill on religious communities, amending an existing law "On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations" to regulate the flow of parishes and other Church property from the old Ukrainian Orthodox Church (under the Moscow Patriarchate) to the newly established one. The laws were controversial, as religion is a sensitive aspect of identity, and Russian state-owned media fanned the flames of local discontent by portraying the legislation as promoting Russophobia (see Section 3).

Language restrictions: In April 2017, the parliament reviewed a bill that would oblige local media outlets to produce at least 75 percent of their content in the Ukrainian language. The bill invited criticism that it constituted a gag on media freedom and could be perceived as promoting Russophobia. When coupled with laws adopted in January 2020 which regulated Russian language instruction and use in Ukrainian schools, a sizable portion of the Ukrainian population felt disenfranchised. Language, like religion, is a resource of the community and is inextricable from identity. [14] Although this was likely intended to curb the Kremlin’s campaign for influence, it may have had the unintended consequence of decreasing public trust in government (see Section 2.2), particularly among Russian-speaking minorities.

Civic space actors were the targets of 42 recorded instances of state-backed legal cases between January 2017 and March 2021 (Table 3), the highest volume occurring in 2017. The most frequent example of cases brought by the government of Ukraine involved individuals accused of sympathizing with Russia or opposing Ukraine. Often, the defendants’ social media posts were presented as evidence of their crimes. As shown in Figure 6, 60 percent of the charges were tied to fundamental freedoms (e.g., freedom of speech, assembly). Thirty-eight percent of the charges were categorized as indirect nuisance charges (e.g., abuse of power, tax evasion) similar to those often used by regimes throughout the region to discredit the reputations of civic space actors. There was one instance where the nature of the charge was coded as “unknown,” as there was insufficient information to make the determination.

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Ukraine

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2017–March 2021

|

Defendant Category |

Number of Cases |

|

Media/Journalist |

6 |

|

Political Opposition |

7 |

|

Formal CSO/NGO |

4 |

|

Individual Activist/Advocate |

9 |

|

Other Community Group |

1 |

|

Other |

15 |

Notes: This table shows the number of state-backed legal cases against civic space actors in Ukraine, disaggregated by the targeted group. This excludes entries related to Russia-occupied Crimea and Donbas, where all entries regardless of type were categorized as harassment/violence. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Ukraine and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Ukraine

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2017–March 2021

Notes: Bar chart of the number of state-backed legal cases brought against civic space actors in Ukraine, disaggregated by targeted group (i.e., political opposition, individual activist/advocate, media/journalist, other community group, formal CSO/NGO or other) and the nature of the charge (i.e., direct or indirect). This excludes entries related to Russia-occupied Crimea and Donbas, where all entries, regardless of type, were categorized as harassment/violence. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Ukraine and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

2.2 Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Ukraine

Prior to the Russian invasion in 2022, Ukraine had seen declining levels of confidence in government, political parties, and the parliament over the past decade, along with consistently low reported interest among Ukrainians in politics. However, Ukrainians’ disenchantment with organized politics stands in sharp contrast to a substantial uptick in their reported participation in other forms of civic life—from increased involvement in demonstrations to growing levels of membership in voluntary organizations, charitable donations, and helping strangers. In this section, we examine how Ukrainians’ interest and engagement in politics, along with less political forms of civic participation, evolved between 2010 and 2021 in the lead up to the outbreak of a hot war with Russia.

2.2.1 Interest in Politics, Willingness to Act, and Membership in Voluntary Organizations

In 2011, two-thirds of Ukrainian respondents to the World Values Survey (WVS) said they were disinterested in politics (Figure 7). An even larger majority (72-88 percent) said they would never take part in political activities such as petitions, boycotts, demonstrations or strikes (Figure 8). Respondents were most likely to have joined a demonstration—but even then, only 14 percent reported doing so. By 2020, there was a movement towards greater political participation—over 40 percent of Ukrainian respondents said they either had participated or would consider participating in a petition or demonstration (Figure 8)—even as a majority remained disinterested in politics (-3 percentage points). [15]

As elsewhere in the region, [16] Ukrainians’ greater willingness to demonstrate may be inspired by seeing large turnouts in response to the 2013–14 Euromaidan protests and the March 2020 protests in Kyiv, as citizens gathered in defiance of a COVID-19 lockdown to rally against President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s perceived concessions to Russia. [17] Relatedly, this could also speak to greater capacity among Ukrainian civil society to engage in advocacy and mobilize the involvement of citizens in mass movements, as described by the CSO Sustainability Index (CSOSI). [18] Yet, Ukraine was not the only country to report an uptick in political participation over the past decade. Other E&E countries not only caught up but ultimately surpassed Ukrainian involvement in protests, boycotts, and petitions by 2020 (Figure 9). [19]

Figure 7. Interest in Politics: Ukrainian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2020

Percentage of Respondents

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of Ukrainian respondents that were interested or not interested in politics in 2011 and 2020, as compared to the regional average. Sources: World Values Survey Wave 6 (2011) and the Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey Wave 2017–2021.

Figure 8. Political Action: Ukrainian Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2011 and 2020

Percentage of Respondents

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of Ukrainian respondents that reported past participation in four types of political action as well as their future willingness to do so. Sources: World Values Survey Wave 6 (2011), and the Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey Wave 2017–2021.

Figure 9. Political Action: Participation by Ukrainian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2020

Percentage of Respondents Reporting “Have Done”

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of Ukrainian respondents who reported past participation in each of four types of political action in 2011 and 2020, as compared to the regional average. Sources: World Values Survey Wave 6 (2011) and the Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey Wave 2017–2021.

Beyond increased involvement in political activities, a growing share of Ukrainians became members of voluntary organizations over the last decade. In 2011, labor unions and churches were the most popular membership organizations in the country, with 12-14 percent of Ukrainian respondents participating (Table 4). [20] By 2020, Ukrainians reported higher levels of membership in nearly every organization type, [21] with the largest gains among churches (+27 percentage points), art organizations (+9 percentage points), and self-help groups (+7 percentage points). Notably, Ukrainians’ expanded engagement in voluntary organizations far outstripped comparable participation rates among their regional peers. Ukrainians’ participation in religious groups exceeded regional membership by 16 percentage points, while Ukraine’s art, environmental, and self-help organizations exceeded the mean by 5 percentage points each.

At the start of the period, Ukrainians’ low levels of membership in organizations was matched by similarly low confidence in the country’s institutions overall. In 2011, 44 percent of Ukrainians were confident in their institutions, trailing the regional average by 11 percentage points. However, this average obscures a deeper crisis of confidence particularly in government, parliament, [22] and political parties which were each distrusted by three-quarters or more of Ukrainians (Table 5). There was greater optimism about other institutions, with churches and religious institutions, [23] environmental organizations, the press, and the military each trusted by the majority of respondents. [24]

Figure 10. Voluntary Organization Membership: Ukrainian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2020

Percentage of Respondents Reporting Membership

Notes: This figure highlights the changes in Ukrainians’ membership in key categories of voluntary organizations from 2011 to 2020, as compared to regional peers. For further details, see Table 4 below. Sources: World Values Survey Wave 6 (2011) and the Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey Wave 2017–2021.

Table 4. Ukrainian Citizens’ Membership in Voluntary Organizations by Type, 2011 and 2020

|

Voluntary Organization |

Membership, 2011 |

Membership, 2020 |

Percentage Point Change |

|

Church or Religious Organization |

11.9% |

27.3% |

+ 15.4 |

|

Sport or Recreational Organization |

7.4% |

13.9% |

+ 6.5 |

|

Art, Music or Educational Organization |

4.4% |

13.5% |

+ 9.1 |

|

Labor Union |

14.5% |

12.5% |

- 1.9 |

|

Political Party |

4.6% |

8.1% |

+ 3.5 |

|

Environmental Organization |

1.3% |

9.2% |

+ 7.9 |

|

Professional Association |

3.2% |

9.4% |

+ 6.2 |

|

Humanitarian or Charitable Organization |

2.8% |

8.7% |

+ 5.8 |

|

Consumer Organization |

2.0% |

5.7% |

+ 3.7 |

|

Self-help Group, Mutual Aid Group |

2.1% |

8.8% |

+ 6.7 |

|

Other Organization |

3.0% |

8.5% |

+ 5.5 |

Notes : This table shows the percentage of Ukrainian respondents that reported membership in various categories of voluntary organizations in 2011 versus 2020. Sources: The World Values Survey Wave 6 (2011) and the Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey Wave 2017–2021.

Although membership in voluntary organizations and confidence in public institutions often go hand-in-hand elsewhere in the region, this was not the case in Ukraine. Even as Ukrainians reported higher membership levels in nearly all types of voluntary organizations in 2020, their confidence in their country’s institutions plummeted across the board, with the exception of the military. [25] The press (-23 percentage points), labor unions (-19 percentage points), and environmental organizations (-17 percentage points) saw the largest declines in public confidence.

At least some of these attitudes may be influenced by the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian war in 2014 and its aftermath, as the Kremlin’s increasingly aggressive use of hybrid tactics in the military and information spheres long preceded the full-scale invasion of Ukraine that came in February 2022. Ukrainians were highly confident in their military even prior to the onset of the 2014 conflict; however, six years of constant warfare against separatist fighters in the Donbas rallied even more of the country behind its armed forces, even in the face of losses. [26] Conversely, Ukrainians’ confidence in their media plummeted by 23 percentage points to 30 percent in 2020, possibly reflecting concerns about the vulnerability of the country’s press in the face of the Kremlin’s second front of attack [27] —a proliferation of disinformation and cyber operations—over the past decade. [28]

Table 5. Ukrainian Confidence in Key Institutions, 2011 and 2020

|

Institution |

Confidence, 2011 |

Confidence, 2020 |

Percentage Point Change |

|

Church or Religious Organizations |

75.2% |

69.6% |

- 5.6 |

|

Military |

58.7% |

70.7% |

+ 12.0 |

|

Environmental Organizations |

55.7% |

38.6% |

-17.1 |

|

Press |

53.0% |

29.6% |

- 23.4 |

|

Labor Unions |

39.2% |

20.6% |

- 18.6 |

|

Government |

25.3% |

18.9% |

-6.4 |

|

Political Parties |

22.1% |

17.8% |

-4.3 |

|

Parliament |

20.5% |

17.9% |

-2.6 |

Notes : This table shows the percentage of Ukrainian respondents that reported confidence in various categories of institutions in 2011 and 2020. Sources: The World Values Survey Wave 6 (2011) and the Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey Wave 2017–2021.

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

The Gallup World Poll’s (GWP) Civic Engagement Index affords an additional perspective on Ukrainian citizens’ attitudes towards less political forms of participation between 2010 and 2021. This index measures the proportion of citizens that reported giving money to charity, volunteering with organizations, and helping a stranger on a scale of 0 to 100. [29] Overall, Ukraine charted its highest civic engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021) period, with corresponding lows in 2011–13 and 2018–19. Donating to charity and helping strangers appeared to be the two key index components driving the overall index score. Although economic performance was correlated with civic engagement scores in several other countries in the region, that did not appear to be the case in Ukraine. [30]

Towards the start of the period (2011–2013), Ukraine’s civic engagement score trailed the regional average, at 23 to 26 points, respectively (Figure 11). During this three-year period, 8 percent of Ukrainian respondents reportedly gave money to charity, 25 percent volunteered at an organization, and 36 percent helped a stranger. [31] Ukraine’s civic engagement scores saw a 6-point increase in 2014 in the aftermath of the Maidan Revolution and the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian War. This increased civic engagement was largely driven by an uptick in charitable donations to 38 percent, even as the share of Ukrainians volunteering decreased to 13 percent and those helping a stranger remained static. [32]

Figure 11. Civic Engagement Index: Ukraine versus Regional Peers

Notes: This figure shows how scores for Ukraine varied on the Gallup World Poll Index of Civic Participation between 2010 and 2021, as compared to the regional mean. Sources: Gallup World Poll, 2010-2021.

The timing of this increase in charitable donations coincides with growing concerns in Ukraine regarding Russia’s military ambitions, as the Ukrainian Army raised $13 million in private donations following the start of the Russo-Ukrainian war in 2014, and many other campaigns emerged to support servicemen and the displaced. [33] Nevertheless, the corresponding decrease in Ukrainians volunteering with organizations raises the question of why this grassroots mobilization in response to war did not necessarily translate from the pocketbook to how Ukrainians spent their time.

It is possible that the answer to this apparent dissonance may lie with how the question was framed in the Gallup World Poll, which asked about “volunteering with an organization.” Respondents may have interpreted this as not including joining mass protest movements or enlisting with the army to defend Ukraine’s borders. Notably, the Civil Society Organization Sustainability Index (CSOSI) for that same year reported a dramatic growth in of volunteerism in support of the Euromaidan protests, families of the Heavenly Hundred, [34] and defending the eastern borders of Ukraine. [35]

Ukraine’s civic engagement receded again in 2018–19, before rallying in the wake of not one but two crises—the 2020 arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic [36] and the 2021 buildup of troops by Russia. [37] The country’s 2020 index improved 22 points compared to the previous year and climbed another 6 points in 2021 (Figure 11). In 2021, 47 percent of Ukrainians reported donating to charity, 24 percent volunteered with an organization, and over 75 percent reported helping a stranger. This upward trend in scores is consistent with improving civic engagement around the world as citizens rallied in response to COVID-19, even in the face of lockdowns and limitations on public gatherings; however, it remains to be seen whether this initial improvement will be sustained in the future. Although respondents were not asked why they engaged in their country’s civic space, the timing of the GWP survey in July 2021 likely meant that the Kremlin’s buildup of 80,000 soldiers on the border in April of that year was top of mind, and there is precedent for similar upswings in civic engagement coinciding with Russian provocations. [38]

Despite serious threats to Ukraine’s sovereignty and security in the face of the Kremlin’s intensifying aggression, there is reason to believe that the country’s civic space will continue to be an important source of resilience and resolve. The Maidan Revolution may have created space for Ukrainian civic actors to emerge, but communities choosing to support each other during the Russo-Ukrainian War and the War in Donbas have fueled the sustained growth of a variety of forms of civic engagement. It remains to be seen whether and how the Kremlin’s military aggression changes perceptions of Ukrainians about their own government in the future. Distrust of government and political parties has worsened since 2011 and likely suffocates citizens’ interest in politics, which has remained static. Working to rebuild public trust in government and interest in political processes will likely be important to the long-term sustainability of Ukraine’s civic space and its ability to endure beyond response to immediate crises.

3. External Channels of Influence: Kremlin Civic Space Projects and Russian State-Run Media in Ukraine

Foreign governments can wield civilian tools of influence such as money, in-kind support, and state-run media in various ways that disrupt societies far beyond their borders. They may work with the local authorities who design and enforce the prevailing rules of the game that determine the degree to which citizens can organize themselves, give voice to their concerns, and take collective action. Alternatively, they may appeal to popular opinion by promoting narratives that cultivate sympathizers, vilify opponents, or otherwise foment societal unrest. While these tools can be used independently, Ukraine is a sobering example where we can see with the benefit of hindsight how the Kremlin employed these instruments of power to soften the ground for conventional military force.

In this section, we analyze data on Kremlin financing and in-kind support to civic space actors or regulators in Ukraine (section 3.1), as well as Russian state media mentions related to civic space, including specific actors and broader rhetoric about democratic norms and rivals (section 3.2). Notably, the Kremlin’s involvement in Ukraine’s civic space differed somewhat from its interactions with other countries in the E&E region, even before Russia’s full-scale military invasion in February 2022. Ukrainian political leaders, in the face of Russia’s financial and military support for separatist militias in the Donbas and the annexation of Crimea, [39] passed legislation and took executive actions (Section 2) to scrutinize the activities of Russian actors, close Russian centers, and otherwise curb the Kremlin’s influence within their borders. Ukraine’s crackdown on Russian cultural centers came both from the bottom up (e.g., the local Lviv council evicting the Russian Pushkin Society from its center on Korolenko street in 2016) [40] and the top down (e.g., President Zelenskyy’s April 2021 sanctions and operational restrictions of Rossotrudnichestvo’s offices and eviction of the Russian State Agency from the country). [41]

In practice, these crackdowns likely inhibited the Kremlin’s ability to replicate in Ukraine one of its common influence tactics from elsewhere in the region: channeling financing and in-kind support to pro-Russian civic actors. This may be why we captured relatively few instances of Russian support to Ukrainian civic space actors or regulators between January 2015 and August 2021, [42] though the Kremlin backed pro-Russian groups in the Donbas. [43] Instead, the Russian government doubled down on another of its tools in Ukraine—international broadcasting—in a bid to influence public attitudes. In fact, Ukraine alone accounted for over half (55 percent) of the nearly 23,000 mentions of civic space actors or democratic rhetoric by two Russian state media outlets across the E&E region between January 2015 and March 2021. We delve into greater detail about these channels of Kremlin influence in Ukraine’s civic space in the remainder of this section.

3.1 Suppliers of Russian State-Backed Support to Ukrainian Civic Space

Although there were fewer documented instances of the Kremlin channeling financing and in-kind support to civic space actors in Ukraine (Figure 12) as compared to other E&E countries, the five examples captured were noticeably consistent in their thematic focus with broader regional trends. Specifically, Russia’s support to Ukrainian and Crimean civic space actors between 2015 and 2021 prioritized youth “patriotic” education, Eurasian integration, and the promotion of narratives centered on increasing federal autonomy for regional governments.

Figure 12. Russian Projects Supporting Civic Space Actors by Type

Number of Projects Recorded, January 2015–August 2021

Notes: This table shows the number of projects directed by the Russian government to either civic space actors or government regulators between January 2015 and August 2021. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

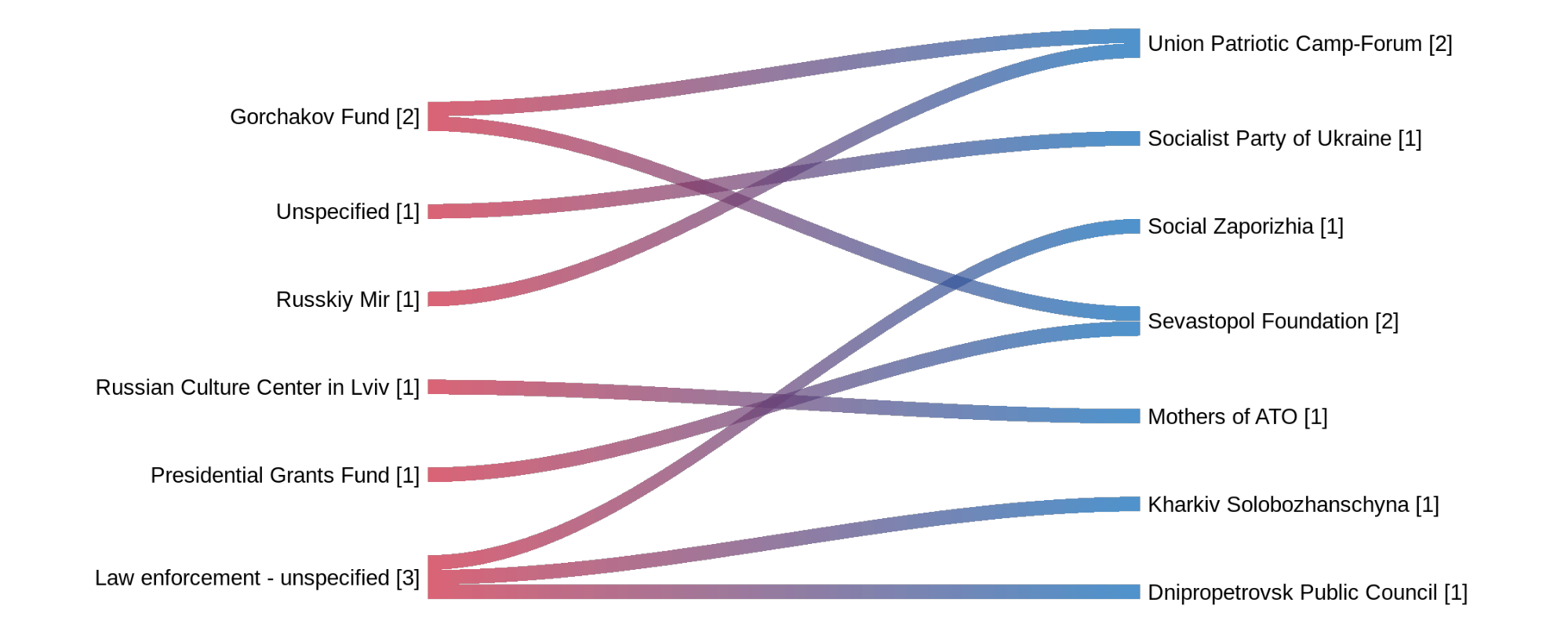

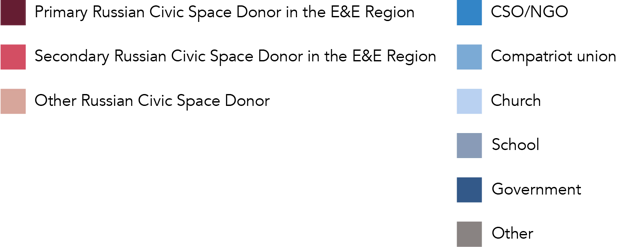

The Kremlin routed its engagements in Ukraine (inclusive of Crimea) through five identified channels (Figure 13), which included language and culture-focused funds, charitable foundations, and the Russian Cultural Center in Lviv. The stated missions of these Russian government entities tend to emphasize themes such as education, culture promotion, and patriotic celebrations of Russia’s military history. However, not all of these Russian state organs were equally important. The Gorchakov Fund, [44] which provides projectized support to NGOs to bolster Russia’s image abroad, was the most prominent organization, writing grants to two Crimean CSOs.

As it often does throughout the region, the Gorchakov Fund partnered with other Kremlin agencies in both of its projects. [45] For example, in May 2021, the Gorchakov Fund and the Presidential Grants Fund together underwrote a conference hosted by the Crimean Foundation for History, Culture, and Development (the Sevastopol Foundation). A few months later, the Gorchakov Fund and the Russkiy Mir Foundation organized the “Union Patriotic Camp-Forum ‘Young Guards Crimea: Donuzlav 2021’” for youth from Crimea, Russia-occupied Donetsk and Luhansk, Russia, and Belarus.

Even in the absence of Rossotrudnichestvo, the above-mentioned Kremlin organs active in Ukraine during the 2015–2021 period generally operated in the same mode: partnering with local organizations in Ukraine (including in occupied Crimea), to promote cultural and educational events with a pro-Russian narrative. These public-facing events sought to leverage and build upon organic local interest among students and the Russian diaspora in Ukraine, which gave the Kremlin plausible deniability of malign intent as it could position these educational activities as innocuous in content and responsive to local demand.

Nevertheless, the Kremlin also engaged in more opaque schemes to influence Ukraine’s civic space. The national head of the Socialist Party of Ukraine, Illia Kiva, reportedly expelled several members of the political party in 2018 for soliciting $30 million in campaign funding for local elections from the Russian government. [46] The Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) found indications of Kremlin activity in several oblasts just west of the Donbas. In February 2017, the SBU identified suspected Kremlin funding of petitions in the local councils of Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk, and Zaporizhzhia, supported by the “Public Council of Dnipropetrovsk Region, Social Zaporizhia, Kharkiv Solobozhanschyna [Sloboda Ukraine].” [47] In September 2017, the SBU uncovered a plot by a Russian Center activist from the Volyn Region to hire and pay 100 protesters 400 hryvnia each to participate in a Lviv protest organized by the mothers of Ukrainian servicemen in the Donbas Security Operation. Perhaps in reaction to the 2016 eviction of its Russian center in Lviv, the Kremlin instead levied its networks in the neighboring region to influence western Ukraine’s largest city.

The Crimean Occupation Authorities are another important set of known Russian actors influencing Ukraine’s civic space. The illegal annexation of Crimea severed many civic actors from their counterparts in Kyiv-controlled Ukraine, and eight years of Russian-backed law enforcement have had a profound impact on the operations of civic actors in the peninsula, as discussed in Section 2.

Figure 13. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Ukrainian Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

Notes: This figure shows which Kremlin-affiliated agencies (left-hand side) were involved in directing financial or in-kind support to which civic space actors or regulators (right-hand side) between January 2015 and August 2021. Lines are weighted to represent counts of projects. The total weight of lines may exceed the total number of projects, due to many projects involving multiple donors and/or recipients. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

3.2 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Ukraine’s Civic Space

The recipients of Kremlin support in Ukraine’s civic space included formal CSOs, youth summer camps, political parties, historical foundations, and false front protestors. Russia focused most of its support to actors in eastern oblasts and occupied Crimea, which is unsurprising given its goal of building a buffer between the Russian state and NATO-friendly nations (Figure 14). The western part of the country still saw Kremlin efforts to influence civic debates, however, with two attempts to buy friends and muddy the political discourse by inflating the appearance of pro-Russian sympathies in Kyiv and Lviv.

Ukraine’s SBU identified attempts by the Kremlin to influence public councils in the eastern capitals of Dnipro, Kharkiv, and Zaporizhzhia, in a bid to turn their oblasts into federally independent regions. [48] Generally following the model of the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and self-declared Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR), three public councils were formed and began to push for increased decentralization of authority to operate their oblasts independent of Kyiv’s oversight. These arguments took many forms and employed common narratives: creating and expanding special economic zones, increasing independence for local groups, and improving trade connectivity with Russia.

Figure 14. Locations of Russian Support to Ukrainian Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

Notes: This map visualizes the distribution of Kremlin-backed support to civic space actors in Ukraine. A more detailed analysis of the flows to Russia-occupied Donetsk and Luhansk can be found in their respective profiles. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

The “Public Council of the Dnipropetrovsk Region,” also known as the “Dnipro Public Council,” was created in 2015 and led by Serhiy Shapran, the local leader of Viktor Medvedchuk’s [49] “Ukrainian Choice” NGO with ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin. [50] The council soon adopted language demanding increased regional autonomy. Similarly, in December 2015, law enforcement broke up a separatist forum organized by the NGO Social Zaporizhia, which had organized a fraudulent congress and promised 200 hryvnias for each vote to create a Zaporizhzhia People’s Republic. [51] Meanwhile, in Kharkiv, Alla Alexandrovskaya, as the head of the “Kharkiv Solobozhanshchyna” movement (also known as the “Slobozhanshchyna” movement) pushed for a bill establishing a special region within the Kharkiv oblast. [52]

All three entities appear to share the same middleman to the Kremlin: Victor Medvedchuk. While it is unclear if Medvedchuk was directly funding the three initiatives, individuals associated with the local offices of “Ukrainian Choice'' acted as nodes to connect these NGOs with the Russian government. [53] The Ukrainian SBU ramped up its scrutiny of separatists in early 2017. Andriy Lesyk, an associate of Medvedchuk, was arrested in December 2017 for repackaging and lobbying for the same separatist agenda as “Kharkiv Solobozhanschyna.” [54] The Prosecutor General’s Office in Kyiv opened an investigation against Medvedchuk in 2019, charging him with suspected treason, and placed him under house arrest in May 2021. [55] The charges were tied to Medvedchuk’s business activities in Russia-occupied Crimea, but this also constrained the Kremlin’s ability to leverage “Ukrainian Choice” to further influence Ukraine’s civic space.

The Kremlin’s efforts to fund civic actors since the 2017 crackdown on “Ukrainian Choice” affiliates highlights Medvedchuk’s importance as a middleman. As mentioned above, an activist from the Russian Culture Center in the Volyn region tried to fund a fake protest rally in Lviv in September 2017. Allegedly organized by the “Mothers of the Donbas Security Operation,” the rally adopted rhetoric used by separatists and Kremlin allies in the Donbas oblasts. There were a number of earlier appeals across the occupied territories by the “Mothers of Donbas'' to end the conflict, which were amplified by the blog “Solidarity with the Antifascist Resistance in Ukraine'' [56] and writer Vladislav Rusanov [57] (a vocal supporter of Donetsk’s “independence”). The petitions were framed as impartial pleas for peace from concerned mothers but criticized the Ukrainian government for failing to protect citizens and withdraw troops.

The fake rally in Lviv intended to use these same themes to stir up unrest in the city and create the illusion that large numbers of Ukrainian citizens in the west of the country were pushing for a unilateral withdrawal from the east. The SBU quickly closed down the operation, as it discovered the activist was using Russian money to pay protesters to march in Lviv. This operation echoed the Kremlin’s earlier attempts to push forward separatist agendas within city councils, but in this case without the endorsement of local politicians to give the rally a semblance of legitimacy.

At the national level, the head of the Socialist Party of Ukraine, Illia Kiva, disclosed in January 2018 that some of his party members had approached Putin’s aide, Vladislav Surkov, to entice the Kremlin to sponsor the party in upcoming elections in exchange for promoting a pro-Russian agenda in Kyiv. The Kremlin’s willingness to consider bankrolling a party that has failed to win a seat in parliament since 2006 (when it captured 6% of the popular vote) to the tune of $30 million reflects the difficulties the Kremlin has had in building political networks in Kyiv after the doors closed on its allies in the eastern oblasts.

3.3 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Ukraine's Civic Space

The Kremlin’s civic space operations in Russia-occupied Crimea grew more frequent and public in 2021, perhaps in a bid to secure popular sympathy in advance of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In May 2021, the Gorchakov and Presidential Grants Funds held a conference with the Crimean Foundation for History, Culture and Development (also known as the Sevastopol Foundation) entitled “The Black Sea Problem in Focus of World Politics.” The conference included a roundtable celebrating Russian history in the peninsula in “Commemoration of the 150th Anniversary of the London Conference of 1871.” In July 2021, the Kremlin funded the Union Patriotic Camp “Young Guards Crimea. Donuzlav – 2021” on the banks of Lake Donuzlav. The youth camp promoted several of the Kremlin’s preferred narratives across the region: celebrating the victory of Soviet forces over the “German-fascist invaders” in World War II and emphasizing Eurasian identity in support of a Eurasian Union.

Russia’s emphasis on its role in defeating the Nazis in “the Great Patriotic War” and attempts to portray its enemies as contemporary Nazis is not unique to Ukraine. Yet, in the aftermath of the February 2022 invasion, the Kremlin’s narrative-building efforts took on greater significance in illuminating Russia’s use of hybrid warfare tactics to build popular support and create a pretext for military intervention. Notably, the Kremlin’s long-standing practice was to portray the fight in the Donbas as protecting citizens from “Ukrainian fascists” and frame the separatist struggle as a crusade against fascism. [58] Some news coverage and academic studies have reported on far-right militias operating in Eastern Ukraine. [59] However, the Kremlin manipulated these fears to stoke a self-serving narrative that countering fascism outweighed concerns of Ukraine’s national sovereignty and justified the ongoing war in Donbas (see Section 3.2).

Eurasian integration was also a central theme in several of the Kremlin’s civic space activities, particularly the framing of the Union Patriotic Camp. In addition to representatives from Russia-occupied Crimea, the camp hosted individuals from Russia, Belarus, and the self-declared Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics, whose flags flew high in a picture documenting the event included in the official press release (Figure 15). The inclusion of a Belarusian delegation at a Crimean youth conference is not surprising, as Russia views Belarus as its co-ambassador for Eurasian integration to promote an economic and political bloc to counter the EU. [60] The presence of the self-declared LPR and DPR at the Union Patriotic Camp foreshadowed the Kremlin’s vision for these two regions to become independent sovereign entities like Belarus, deeply enmeshed in Russia’s political and economic sphere of influence, under the banner of “Eurasian integration.” Seven months later, Putin formalized this view by officially recognizing the two regions as independent states. [61]

Even in advance of the February 2022 invasion, civic space within Kyiv-controlled Ukraine had grown more resistant to the Kremlin’s attempts to undermine it. But in Russia-occupied Crimea, Luhansk, and Donetsk, the Kremlin was able to act with greater impunity in using multiple channels of influence to promote pro-Russian narratives on the ground. In hindsight, this underscores the unique vulnerabilities of occupied territories throughout the E&E region as the first, and arguably easiest, entry points for the Kremlin to expand its sphere of influence. Yet, as we have seen in Ukraine, the Kremlin’s pro-independence and anti-fascism narrative building can have far-reaching effects outside of the occupied territories themselves.

Figure 15. Young Guards of Crimea in the Union Patriotic Camp in the Donbas, 2021

Notes: The Gorchakov Fund-sponsored event in July 2021 flew flags from Russia, Belarus, and several separatist regions. Source: Photo by Donbas State Technical University, under fair use.

3.4 Russian Media Mentions Related to Civic Space Actors and Democratic Rhetoric

Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced Ukrainian civic actors a total of 5,993 times from January 2015 to March 2021. [62] Approximately two-thirds of these mentions (3,995 instances) were of domestic actors, while the remaining one-third (1,998 instances) focused on foreign and intergovernmental actors. Russian state media mentioned 516 organizations by name and 235 informal groups. In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of Ukrainian citizens, we also analyzed 6,563 mentions by Russian state media of five keywords in conjunction with Ukraine: North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO, the United States, the European Union, democracy, and the West.

3.4.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Ukrainian Civic Space Actors

Forty-seven percent of Russian media mentions of domestic civic actors in Ukraine referred to specific groups by name. The 289 named domestic actors represent a diverse cross-section of organizational types, ranging from political parties to civil society organizations and media outlets. Media organizations (542 mentions), “nationalist paramilitary groups” (515 mentions), [63] and political parties (310 mentions) were most frequently mentioned. Russian state media mentions of named domestic actors were most often neutral (64 percent) or negative (34 percent) in tone. Positive mentions were scarce (2 percent).

Russian state media most often referenced domestic Ukrainian media as source material for local coverage of events of interest, such as the War in Donbas and protests in Kyiv. Kremlin-affiliated media mentioned the Donetsk News Agency, the main newspaper for the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR), 117 times (20 percent of all domestic media mentions). [64] Similarly, they provided a megaphone for the LuganskInformCenter in Russia-occupied Luhansk, citing the outlet 30 times. In addition, the Kremlin amplified local pro-Russian newspapers in Ukraine, broadcasting messages through local outlets such as 112 Ukraine Television Channel (48 mentions), Vesti (19 mentions), Ukrainian Independent News Agency (UNIAN) (16 mentions), Strana.ua (16 mentions), and Inter TV (16 mentions).

Nationalist paramilitary groups attracted the most negative coverage (89 percent negative mentions) among named domestic civic space actors. Russian state media portrayed nationalist organizations as hijacking the Euromaidan protests, which helped overthrow the Yanukovich regime, and controlling the government in Kyiv, which allegedly allowed them to commit brazen acts of violence against pro-Kremlin actors with impunity. As elsewhere in the E&E region, this line of rhetoric also advances one of the Kremlin’s preferred narratives: that Russia is the natural defender of conservative values and a bulwark against the dangerous spread of neo-Nazism. In this case, co-opting controversial nationalist radical organizations as the face of, and force behind, grassroots activism is best understood as a tactic to discredit civil society movements in Ukraine and is an important tool of influence in the Kremlin’s state media arsenal:

- A January 2015 Sputnik article argued, "Moscow has repeatedly expressed concern over the rise of neo-Nazism in Ukraine. Far-right groups were actively involved in the overthrow of former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych in February last year and have also been engaged in Kyiv's military operation against independence supporters in the country’s predominantly Russian-speaking eastern regions.” [65]

- A June 2017 Sputnik article continued this refrain, “the Ukrainian authorities did not do anything to remove the violent 'civic activists' who prevented the lines from being repaired, beating and insulting the repair teams. These Ukrainian 'civic activists'...included...the veterans of the neo-Nazi Azov battalion and the Right Sector group, made infamous by their suppression of the population of Donbas.” [66]

The organization Right Sector (297 mentions in non-militant contexts) was a favorite target of Russian state media attention—attracting 267 negative references (90 percent). Kremlin-affiliated media blamed the group for the alleged “Odessa Massacre of 2014,” which resulted in the deaths of 48 activists. As highlighted in a 2015 TASS segment, "radicals from the far-right Ukraine’s Right Sector movement, which is banned in Russia...burnt a tent camp in Odessa where the city residents were collecting signatures in support of the referendum on Ukraine’s federalization and the granting of state status to the Russian language. The federalization supporters found shelter in the House of Trade Unions, which was later surrounded by the Right Sector militants who set the building on fire. As a result, 48 people [were] burnt alive and over 200 were injured.” [67] Although multiple international organizations, including the Council of Europe and the May 2 Group, determined that the deaths at the Odessa Trade Union House were not caused by intentional arson, [68] Russian state media ignored this evidence, blaming the Right Sector to advance the narrative that extremist organizations dominate Ukrainian civil society.