Turkmenistan: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence

Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, Lincoln Zaleski

April 2023

[Skip to Table of Contents] [Skip to Chapter 1]Executive Summary

This report surfaces insights about the health of Turkmenistan’s civic space and vulnerability to malign foreign influence in the lead up to Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Research included extensive original data collection to track Russian state-backed financing and in-kind assistance to civil society groups and regulators, media coverage targeting foreign publics, and indicators to assess domestic attitudes to civic participation and restrictions of civic space actors. Further reinforcing the fact that the Kremlin does not employ a one-size fits all strategy, Moscow’s engagement with civic space actors was noticeably absent as compared to other countries in the region. Instead, the Kremlin focused its attention more squarely on Turkmenistan's chief executive.

The analysis was part of a broader three-year initiative by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to produce quantifiable indicators to monitor civic space resilience in the face of Kremlin influence operations over time (from 2010 to 2021) and across 17 countries and 7 occupied or autonomous territories in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). Below we summarize the top-line findings from our indicators on the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Turkmenistan, as well as channels of Russian malign influence operations:

- Restrictions of Civic Actors: Turkmen civic space actors were the targets of 124 restrictions between January 2017 and March 2021. Eighty-six percent of these restrictions involved harassment or violence, followed by state-backed legal cases (11 percent), and newly proposed or implemented restrictive legislation (3 percent). The most prominent spike in restrictions was in mid-2020 following a deadly hurricane which coincided with authorities doubling down on efforts to silence critics. Other community groups were most frequently targeted, followed by journalists, and the Turkmen government was the primary initiator. There were three recorded instances of restrictions involving the Turkish government cooperating with Turkmen authorities to constrain civic space.

- Attitudes Towards Civic Participation: Ninety-five and seventy-nine percent of Turkmen respondents “strongly” or “somewhat” trusted the media in 2018 and 2019, respectively. There was a more pronounced loss of confidence in newspapers (-14 percentage points) and radio (-24 percentage points), as compared to television, between the two survey waves. Turkmen citizens reported higher participation in less political forms of civic engagement than their regional peers between 2011 and 2019. Over a nine-year period, 36 percent of Turkmen citizens gave money to charity, 39 percent volunteered, and 54 percent helped a stranger, on average. Turkmenistan’s civic engagement reached a high in 2019, when 73 percent of citizens reported helping a stranger. There was no data available to assess the level of more political forms of civic engagement or public trust in institutions other than the media.

- Russian-backed Civic Space Projects: The Kremlin supported two Turkmen civic organizations via two projects between January 2015 and August 2021; however, the nature of its support differed from its typical approach elsewhere in the E&E region. Turkmenistan attracted the second-lowest level of Russian civic space activities which were exclusively channeled towards civic space regulators, centered on bilateral security cooperation, and narrowly involved the security services and presidency.

- Russian State-run Media: Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News mentions of civic space actors in Turkmenistan were extremely sparse. The two agencies referenced 2 external civic actors and 1 informal group 4 times from January 2015 to March 2021. The overall tone of these mentions was largely neutral and there were no mentions of domestic Turkmen civic actors. Coverage of the U.S. was limited to 2 instances: a positive reference to the help of U.S. allies during the 72nd anniversary of Victory Day and a negative reference to the U.S. “Greater Central Asia project.”

Table of Contents

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Turkmenistan

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Turkmenistan: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

2.2 Attitudes Toward Civic Space in Turkmenistan

2.2.1 Trust in Information via Television, Newspapers, and Radio

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to Turkmenistan’s Civic Space

3.1.1 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Turkmenistan’s Civic Space

3.1.2 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Turkmenistan's Civic Space

3.2 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

3.2.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in Turkmenistan’s Civic Space

3.2.3 Russian State Media’s Focus on Turkmenistan’s Civic Space over Time

3.2.4 Russian State Media Coverage of Western Institutions and Democratic Norms

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

5.3 Russian Projectized Support to Civic Space Actors or Regulators

5.4 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

Figures and Tables

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of Turkmen Civic Space Actors

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Turkmenistan

Figure 2. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Turkmenistan

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Turkmenistan

Figure 3. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Turkmenistan by Initiator

Figure 5. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Turkmenistan

Table 4. Citizen Trust of Media Institutions in Turkmenistan, 2018 and 2019

Figure 6. Civic Engagement Index: Turkmenistan versus Regional Peers

Figure 7. Russian Projects Supporting Turkmen Civic Space Actors by Type

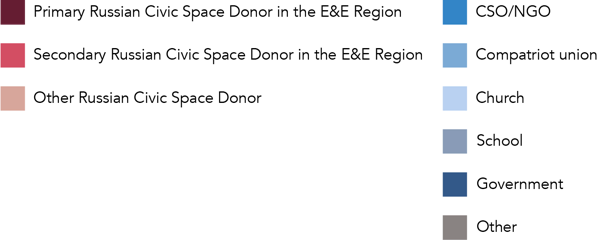

Figure 8. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Turkmen Civic Space

Figure 9. Locations of Russian Support to Turkmen Civic Space

Table 5. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Turkmenistan by Sentiment

Figure 10. Russian State Media Mentions of Turkmen Civic Space Actors

Table 6. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, and Lincoln Zaleski. John Custer, Sariah Harmer, Parker Kim, and Sarina Patterson contributed editing, formatting, and supporting visuals. Kelsey Marshall and our research assistants provided invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report including: Jacob Barth, Kevin Bloodworth, Callie Booth, Catherine Brady, Temujin Bullock, Lucy Clement, Jeffrey Crittenden, Emma Freiling, Cassidy Grayson, Annabelle Guberman, Sariah Harmer, Hayley Hubbard, Hanna Kendrick, Kate Kliment, Deborah Kornblut, Aleksander Kuzmenchuk, Amelia Larson, Mallory Milestone, Alyssa Nekritz, Megan O’Connor, Tarra Olfat, Olivia Olson, Caroline Prout, Hannah Ray, Georgiana Reece, Patrick Schroeder, Samuel Specht, Andrew Tanner, Brianna Vetter, Kathryn Webb, Katrine Westgaard, Emma Williams, and Rachel Zaslavsk. The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

This research was made possible with funding from USAID's Europe & Eurasia (E&E) Bureau via a USAID/DDI/ITR Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) cooperative agreement (AID-A-12-00096). The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

A Note on Vocabulary

The authors recognize the challenge of writing about contexts with ongoing hot and/or frozen conflicts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consistently label groups of people and places for the sake of data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that terminology is political, but our use of terms should not be construed to mean support for one faction over another. For example, when we talk about an occupied territory, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the government in the capital. Or, when we analyze the de facto authorities’ use of legislation or the courts to restrict civic action, it is not to grant legitimacy to the laws or courts of separatists, but rather to glean meaningful insights about the ways in which institutions are co-opted or employed to constrain civic freedoms.

Citation

Custer, S., Mathew, D., Burgess, B., Dumont, E., Zaleski, L. (2023). Turkmenistan: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence . April 2023. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William and Mary.

1. Introduction

How strong or weak is the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Turkmenistan? To what extent do we see Russia attempting to shape civic space attitudes and constraints in Turkmenistan to advance its broader regional ambitions? Over the last three years, AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—has collected and analyzed vast amounts of historical data on civic space and Russian influence across 17 countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). [1] In this country report, we present top-line findings specific to Turkmenistan from a novel dataset which monitors four barometers of civic space in the E&E region from 2010 to 2021 (see Table 1). [2] Due to the challenging survey environment of Turkmenistan, and logistical difficulties due to the COVID-19 pandemic, some indicators used in other E&E countries were unavailable.

For the purpose of this project, we define civic space as: the formal laws, informal norms, and societal attitudes which enable individuals and organizations to assemble peacefully, express their views, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. [3] Here we provide only a brief introduction to the indicators monitored in this and other country reports. However, a more extensive methodology document is available via aiddata.org which includes greater detail about how we conceptualized civic space and operationalized the collection of indicators by country and year.

Civic space is a dynamic rather than static concept. The ability of individuals and organizations to assemble, speak, and act is vulnerable to changes in the formal laws, informal norms, and broader societal attitudes that can facilitate an opening or closing of the practical space in which they have to maneuver. To assess the enabling environment for Turkmenistan’s civic space, we examined two indicators: restrictions of civic space actors (section 2.1) and citizen attitudes towards civic space (section 2.2). Because the health of civic space is not strictly a function of domestic dynamics alone, we also examined two channels by which the Kremlin could exert external influence to dilute democratic norms or otherwise skew civic space throughout the E&E region. These channels are Russian state-backed financing and in-kind support to government regulators or pro-Kremlin civic space actors (section 3.1) and Russian state-run media mentions related to civic space actors or democracy (section 3.2).

Since restrictions can take various forms, we focus here on three common channels which can effectively deter or penalize civic participation: (i) harassment or violence initiated by state or non-state actors; (ii) the proposal or passage of restrictive legislation or executive branch policies; and (iii) state-backed legal cases brought against civic actors. Citizen attitudes towards political and apolitical forms of participation provide another important barometer of the practical room that people feel they have to engage in collective action related to common causes and interests or express views publicly. In this research, we monitored responses to citizen surveys related to: (i) interest in politics; (ii) past participation and future openness to political action (e.g., petitions, boycotts, strikes, protests); (iii) trust or confidence in public institutions; (iv) membership in voluntary organizations; and (v) past participation in less political forms of civic action (e.g., donating, volunteering, helping strangers).

In this project, we also tracked financing and in-kind support from Kremlin-affiliated agencies to: (i) build the capacity of those that regulate the activities of civic space actors (e.g., government entities at national or local levels, as well as in occupied or autonomous territories ); and (ii) co-opt the activities of civil society actors within E&E countries in ways that seek to promote or legitimize Russian policies abroad. Since E&E countries are exposed to a high concentration of Russian state-run media, we analyzed how the Kremlin may use its coverage to influence public attitudes about civic space actors (formal organizations and informal groups), as well as public discourse pertaining to democratic norms or rivals in the eyes of citizens.

Although Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine February 2022 undeniably altered the civic space landscape in Turkmenistan and the broader E&E region for years to come, the historical information in this report is still useful in three respects. By taking the long view, this report sheds light on the Kremlin’s patient investment in hybrid tactics to foment unrest, co-opt narratives, demonize opponents, and cultivate sympathizers in target populations as a pretext or enabler for military action. Second, the comparative nature of these indicators lends itself to assessing similarities and differences in how the Kremlin operates across countries in the region. Third, by examining domestic and external factors in tandem, this report provides a holistic view of how to support resilient societies in the face of autocratizing forces at home and malign influence from abroad.

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

|

Civic Space Barometer |

Supporting Indicators |

|

Restrictions of civic space actors (January 2017–March 2021) |

|

|

Citizen attitudes toward civic space (2011–2019)

|

|

|

Russian projectized support relevant to civic space (January 2015–August 2021) |

|

|

Russian state media mentions of civic space actors (January 2015–March 2021) |

|

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Turkmenistan

A healthy civic space is one in which individuals and groups can assemble peacefully, express views and opinions, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. Laws, rules, and policies are critical to this space, in terms of rights on the books (de jure) and how these rights are safeguarded in practice (de facto). Informal norms and societal attitudes are also important, as countries with a deep cultural tradition that emphasizes civic participation can embolden civil society actors to operate even absent explicit legal protections. Finally, the ability of civil society actors to engage in activities without fear of retribution (e.g., loss of personal freedom, organizational position, and public status) or restriction (e.g ., constraints on their ability to organize, resource, and operate) is critical to the practical room they have to conduct their activities. If fear of retribution and the likelihood of restriction are high, this has a chilling effect on the motivation of citizens to form and participate in civic groups.

In this section, we assess the health of civic space in Turkmenistan over time in two respects: the volume and nature of restrictions against civic space actors (section 2.1) and the degree to which Turkmen engage in a range of political and apolitical forms of civic life (section 2.2).

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Turkmenistan: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time

Turkmen civic space actors experienced 124 known restrictions between January 2017 and March 2021 (see Table 2). These restrictions were weighted toward instances of harassment or violence (86 percent). There were fewer instances of state-backed legal cases (11 percent) and newly proposed or implemented restrictive legislation (3 percent); however, these can have a multiplier effect in creating a legal mandate for a government to pursue other forms of restriction. These imperfect estimates are based upon publicly available information either reported by the targets of restrictions, documented by a third-party actor, or covered in the news (see Section 5). [4]

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of Turkmen Civic Space Actors

|

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021-Q1 |

Total |

|

Harassment/Violence |

21 |

17 |

20 |

48 |

0 |

106 |

|

Restrictive Legislation |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

|

State-backed Legal Cases |

5 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

0 |

14 |

|

Total |

26 |

20 |

22 |

56 |

0 |

124 |

Instances of restrictions of Turkmen civic space actors were unevenly distributed across this time period (Figure 1). There are no instances recorded in the first quarter of 2021. This may be due to the strict media environment in Turkmenistan, which has consistently ranked in the bottom 3 countries of the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index from 2017 to 2021. There is a prominent spike in the number of restrictions in 2020, the bulk of which took place in July 2020. Turkmenistan was hit by a deadly hurricane in May 2020, resulting in death and destruction of property. Instead of focusing on relief and rebuilding, the authorities doubled down on efforts to silence critics. Citizens who shared images of the damage done by the hurricane were arrested. In some cases, when the dissidents were abroad, their families in Turkmenistan were called in for questioning and harassed by the police.

Other community groups (coded as “other”) were more frequently mentioned in recorded instances of harassment or violence in Turkmenistan than those working for formally registered CSOs and NGOs, or members of the media (Figure 2). This “other” group includes citizens suspected of sharing photos detailing government inaction with media outlets, university students accused of visiting “hostile” websites [5] , and women threatened with arrest for complaining about the shortage of flour at the office of the local administration. [6] Journalists and media outlets were the second most-targeted group.

Compared to other E&E countries, political opposition members were noticeably absent from the recorded instances of restriction; however, this is most likely indicative of the extremely constrained space for political debate. Despite the appearance of a multi-party system, in practice the Democratic Party of Turkmenistan is the dominant political party and all other legally recognized parties support the government. [7] Political movements opposed to the Democratic Party of Turkmenistan exist in exile, but are not allowed to operate within the country or participate in elections.

The Turkmen government was the most prolific initiator of restrictions of civic space actors accounting for 94 recorded mentions. Turkmen authorities visited the homes of activists and ordinary citizens alike, threatening consequences for those who spoke out against corruption or “liked” social media posts critical of the government (Figure 3). Domestic non-governmental actors were identified as initiators in 2 restrictions and there were several incidents involving unidentified assailants (10 mentions). By virtue of the way that the indicator was defined, the initiators of state-backed legal cases are either explicitly government agencies and government officials or clearly associated with these actors (e.g., the spouse or immediate family member of a sitting official).

There were three recorded instances of restrictions of civic space actors involving the Turkish government cooperating with Turkmen authorities to constrain civic space:

- In July 2020, Turkmen citizens were detained by Turkish police while protesting in Istanbul in two separate incidents. Concurrently, the parents of the detainees, who lived in Turkmenistan, were questioned and threatened by the local police.

- In October 2020, Turkmen activists living in Turkey attempted to hold a protest outside of Turkmenistan’s consulate in Istanbul. Consulate staff informed the Turkish police, who sent police officers and armed security guards to inform the protestors that they would not be allowed to hold their rally due to COVID-19 restrictions. In connection with the planned protest, the Turkish police also detained two activists on accusations of migration violations.

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Turkmenistan

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment/Violence

Restrictive Legislation

State-backed Legal Cases

Key Events Relevant to Civic Space in Turkmenistan

|

February 2017 |

President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov gains a third term in office with 98% of the vote. Amendments to the Law on the President (approved before the elections) allow for a transition of power only if the president is no longer able to fulfill his responsibilities. |

|

September 2017 |

Recently adopted Constitutional amendments increase the presidential term from five to seven years and scrap the 70-year age limit for the office. |

|

October 2017 |

Russian President Vladimir Putin meets with Turkmenistan's president on a rare visit to the gas-rich Central Asian nation. |

|

March 2018 |

Parliamentary elections are held that include candidates from three parties and some independents, but no real opposition to President Berdymukhamedov. Serdar Berdymukhamedov, the son of the authoritarian president, is appointed the deputy minister of foreign affairs. |

|

September 2019 |

Media watchdog Committee to Protect Journalists lists Eritrea as the world’s most censored state, with North Korea and Turkmenistan 2nd and 3rd. |

|

February 2020 |

President Berdymukhamedov named his son, Serdar, minister of industry and construction. Serdar oversees the building of a new capital from scratch for the central Ahal province, which he used to head. |

|

June 2020 |

President Berdymukhamedov spearheads a cycling parade to mark World Bicycle Day, with thousands of tracksuit-wearing officials brought along for a ride. World Bicycle Day was recognized by the UN in 2018 following a proposal by Turkmenistan. |

Figure 2. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Turkmenistan

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2017–March 2021

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Turkmenistan

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2017–March 2021

|

Defendant Category |

Number of Cases |

|

Media/Journalist |

1 |

|

Political Opposition |

0 |

|

Formal CSO/NGO |

0 |

|

Individual Activist/Advocate |

6 |

|

Other Community Group |

3 |

|

Other |

4 |

Figure 3. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Turkmenistan by Initiator

Number of Instances Recorded

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

Instances of harassment (10 threatened, 86 acted upon) towards civic space actors were more common than episodes of outright physical harm (2 threatened, 8 acted-upon) during the period. The vast majority of these restrictions (89 percent) were acted upon, rather than merely threatened. However, since this data is collected on the basis of reported incidents, this likely understates threats which are less visible (see Figure 4). Of the 106 instances of harassment and violence, acted-on harassment counted for the largest percentage (81 percent).

Figure 4. Threatened versus Acted-on Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Turkmenistan

Number of Instances Recorded

Recorded instances of restrictive legislation in Turkmenistan were relatively few in number (4) but are important to capture as they give government actors a mandate to constrain civic space with long-term cascading effects. This indicator is limited to a subset of parliamentary laws, chief executive decrees or other formal executive branch policies and rules that may have a deleterious effect on civic space actors, either subgroups or in general. Both proposed and passed restrictions qualify for inclusion, but we focus exclusively on new and negative developments in laws or rules affecting civic space actors. We exclude discussion of pre-existing laws and rules or those that constitute an improvement for civic space.

Compared to other E&E countries, executive branch policies were a relatively more common form of restrictive legislation targeting civic space actors in Turkmenistan than parliamentary proceedings. In January 2018, the new Law on TV and Radio Broadcasting came into effect, emphasizing the importance of promoting a positive image of Turkmenistan through TV and radio broadcasts. The law used wording reminiscent of President Gurbanguly’s repeated statements that national media outlets should ensure their coverage popularized the achievements of the country. Travel restrictions were frequently used by Turkmen authorities to blacklist out-of-favor former officials, civil society activities, journalists, religious leaders, and their family members and prohibit them from leaving the country for undisclosed reasons.

The Turkmen government proved creative in exploiting the COVID-19 pandemic as a pretext to constrain civic space in various ways. Turkmen authorities put in place executive orders to prevent people from talking about the coronavirus or anything that would suggest a lack of confidence in the authorities’ handling of the pandemic. The police were ordered to disperse any crowds of people to prevent the spread of coronavirus, despite earlier in the year promoting mass events to mark World Health Day, paying no heed to the World Health Organization’s social distancing guidelines.

Civic space actors were the targets of 14 recorded instances of state-backed legal cases between January 2017 and March 2021. The highest concentration of these cases (6) occurred in 2020. Most frequently Turkmen authorities pursued cases against both ordinary citizens and activists in retaliation for expressing critical views of the government. As shown in Figure 5, charges in these cases were most often (50 percent) directly tied to fundamental freedoms (e.g., freedom of speech, assembly.) There were fewer indirect nuisance charges (29 percent), such as illegal possession of drugs or “unsanitary conditions caused by an excessive number of pets” [8] , intended to discredit the reputations of civic space actors. In the remaining cases (21 percent), details were insufficient to classify the nature of the charge.

Figure 5. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Turkmenistan

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2017–March 2021

2.2 Attitudes Toward Civic Space in Turkmenistan

Due to the extremely restrictive environment of Turkmenistan, many of the indicators used to assess citizen attitudes towards civic space and institutions in other E&E countries were unavailable here. [9] In this profile, we instead exclusively focus on citizens’ trust in media per the Central Asian Barometer [10] and the extent of apolitical forms of civic engagement via the Gallup World Poll’s Civic Engagement Index. Trust in the media remained high, but declined between 2018 and 2019, perhaps as a reaction to the Law on TV and Radio Broadcasting. Turkmen citizens reported higher apolitical civic engagement than regional peers. In this section, we take a closer look at Turkmen citizens’ trust in media outlets. We also examine how Turkmen involvement in less political forms of civic engagement—donating to charities, volunteering for organizations, helping strangers—has evolved over time.

2.2.1 Trust in Information via Television, Newspapers, and Radio

Citizens’ overall trust in the media was surprisingly strong in Turkmenistan—95 and 79 percent of Turkmen respondents to the Central Asia Barometer said they “strongly” or “somewhat” trusted the media in surveys conducted in 2018 and 2019, respectively. This was on par or higher than Central Asian peers such as Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. [11] These aggregate measures obscure a deeper insight that Turkmen citizens’ declining trust varied somewhat by type of media. Between the two survey waves, television fared the best (-7 percentage points), with a more pronounced loss in confidence related to newspapers (-14 percentage points) and radio (-24 percentage points). Table 4 provides a breakdown of the results by survey wave and type of media. It is important to note that while the survey questions gauge levels of public trust, they do not speak to the accuracy or independence of the media. [12]

Table 4. Citizen Trust of Media Institutions in Turkmenistan, 2018 and 2019

|

Media Type |

"Strongly Trust" Wave 4 - November 2018 |

"Strongly Trust" Wave 5 - May 2019 |

Percentage Point Change in "Strongly Trust" |

"Trust somewhat" Wave 4 - November 2018 |

"Trust somewhat" Wave 5 - May 2019 |

Percentage Point Change in "Trust Somewhat" |

|

TV |

61% |

57% |

-4 |

37% |

34% |

-3 |

|

Newspaper |

58% |

45% |

-13 |

36% |

35% |

-1 |

|

Radio |

62% |

46% |

-16 |

29% |

21% |

-8 |

|

Average |

61% |

49% |

-11 |

34% |

30% |

-4 |

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

The Gallup World Poll’s (GWP) Civic Engagement Index affords an additional perspective on Turkmen citizens’ attitudes towards less political forms of participation between 2011 and 2019. This index measures the proportion of citizens that reported giving money to charity, volunteering at organizations, and helping a stranger on a scale of 0 to 100. [13] Overall, Turkmenistan charted the highest civic engagement scores on the index in 2015 and 2019, with lows in 2014 and 2016.

Turkmenistan surpassed its E&E regional peers by approximately 15 points each year from 2011 to 2019—an average of 43 versus 28 points respectively (Figure 6). [14] During this nine-year period, 36 percent of Turkmen respondents on average reportedly gave money to charity, 39 percent volunteered at an organization, and 54 percent helped a stranger. Nevertheless, there was a high degree of volatility during the period. Turkmenistan’s civic engagement scores plummeted in 2014, [15] the same year that the government made significant cuts to their system of subsidies funded by natural gas revenue. [16] Civic engagement rebounded in 2015, [17] despite an economic slowdown, as Turkmen authorities issued a law permitting some forms of public assembly, albeit with “stark restrictions.” [18] Gains were reversed in 2016, before Turkmenistan’s performance on the index rallied for three consecutive years, reaching a high of 52 points in 2019 when 73 percent of citizens reported helping a stranger. [19]

Elsewhere in Central Asia, donating to charity and helping strangers appeared to be weakly and positively correlated with the overall performance of the economy. However, in Turkmenistan, there was no statistically significant link between these facets of civic engagement and the economy. Instead, political and social factors may have influenced Turkmenistan’s large swings on the index over the years. There was no Gallup data for Turkmenistan in 2020 or 2021, but broader regional trends suggest that it may be reasonable to assume that civic engagement increased or held steady during the COVID-19 crisis.

Figure 6. Civic Engagement Index: Turkmenistan versus Regional Peers

3. External Channels of Influence: Kremlin Civic Space Projects and Russian State-Run Media in Turkmenistan

Foreign governments can wield civilian tools of influence such as money, in-kind support, and state-run media in various ways that disrupt societies far beyond their borders. They may work with the local authorities who design and enforce the prevailing rules of the game that determine the degree to which citizens can organize themselves, give voice to their concerns, and take collective action. Alternatively, they may appeal to popular opinion by promoting narratives that cultivate sympathizers, vilify opponents, or otherwise foment societal unrest. In this section, we analyze data on Kremlin financing and in-kind support to civic space actors or regulators in Turkmenistan (section 3.1), as well as Russian state media mentions related to civic space, including specific actors and broader rhetoric about democratic norms and rivals (section 3.2).

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to Turkmenistan’s Civic Space

The Kremlin supported two known Turkmen entities via two civic space-relevant projects in Turkmenistan between January 2015 and August 2021 (Figure 7). Moscow’s projectized support to Turkmenistan’s civic space differs from how it engages with other E&E countries. Turkmenistan attracted the second-lowest level of Russian civic space activities, only surpassing Kosovo (which the Kremlin does not formally recognize) in the number of projects and recipient organizations. Russian authorities focused on building the capacity of civic space regulators—the President of Turkmenistan and the State Security Council—rather than local civil society organizations. Rather than the usual emphasis on compatriot unions and cultural promotion, the Kremlin’s projects in Turkmenistan instead centered on promoting bilateral security cooperation.

This status quo could be symptomatic of a relatively constrained environment for formal civil society organizations to operate in Turkmenistan, which would limit the number of non-governmental partners with which the Kremlin could conceivably partner.

Figure 7. Russian Projects Supporting Turkmen Civic Space Actors by Type

Number of Projects Recorded, January 2015–August 2021

Elsewhere in the E&E region, the Kremlin taps an array of executive agencies and ministries, most notably Rossotrudnichestvo and the Gorchakov Fund, to engage with civic space actors and regulators. This was not the case in Turkmenistan. The Gorchakov Fund, whose activities typically center on funding formal civil society organizations to undertake pro-Russian projects, likely ran into Turkmenistan’s restrictions of foreign funding for public associations. [20] Rossotrudnichestvo similarly did not partner with any Turkmen civil society organizations, instead conducting only limited public diplomacy and consular activities such as hosting lectures on poets, [21] promoting study abroad in Russia, [22] and hosting a Mother’s Day drawing and photo competition in 2020. [23]

Instead, Russian President Putin chose to interact with civic space regulators directly such as Turkmen President Berdymukhamedov and Turkmenistan’s State Security Council (Figure 8). In May 2018, representatives of the Security Council of the Russian Federation met with the State Security Council of Turkmenistan in Ashgabat for an intergovernmental meeting to discuss improving joint information security. [24] In November 2020, President Putin signed the “Federal Law On Ratification of the Agreement between the Russian Federation and Turkmenistan on Cooperation in the Area of Security,” [25] after it was approved by Russia and Turkmenistan’s parliamentary bodies. [26]

Figure 8. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Turkmen Civic Space

Number of Projects Recorded, 2015–2021

3.1.1 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Turkmenistan’s Civic Space

Many of the usual channels for Russian authorities to build ties with civic space actors—local civil society organizations, compatriot unions, and religious groups—are less feasible in Turkmenistan. Formally registered CSOs are few in number (118), predominantly focused on sports (40 percent), [27] and subject to extremely restrictive laws on their operations and funding. [28] Relatedly, Turkmen authorities have restricted independent political activity by ethnic or religious minorities. [29] Given the limited alternatives, the Kremlin instead opted for more personalized engagement with Turkmenistan’s chief executive and his closest advisors in the capital city of Ashgabat.

The Turkmenistan State Security Council and the counterpart Security Council of the Russian Federation are consultative bodies, which Presidents Berdymukhamedov and Putin use to personally communicate and coordinate security policy. President Putin himself pushed the 2020 cooperation agreement with Turkmenistan forward, likely using the promise of aid to President Berdymukhamedov to ensure that Turkmen government signed on to the document. [30] Neither this outreach, nor Russia’s decision to focus on Turkmenistan’s State Security Council were surprising, given the high degree of centralization of decision-making in Turkmenistan and the lack of alternative partners.

Figure 9. Locations of Russian Support to Turkmen Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

3.1.2 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Turkmenistan's Civic Space

The Kremlin focused its civic-space relevant activities in Turkmenistan exclusively on expanding security cooperation between Moscow and Ashgabat. Not all forms of security cooperation are relevant to civic space (e.g., joint military exercises), but the 2018 consultation and 2020 agreement were sufficiently broad as to raise concerns that the Turkmen authorities would leverage support from the Kremlin to further increase surveillance of, and control over, citizens’ activities.

The 2020 agreement mandated cooperation on a range of issues—from counter-terrorism to economic crimes—and called for new information exchange mechanisms. [31] The objectives included the countries’ intention to work together to “suppress the activities of terrorist and extremist organizations,” as well as “ fight against organized crime, economic crimes, crimes against transport safety, [and] illicit trafficking in narcotic drugs.” [32] Turkmen authorities can easily exploit such broad language, along with enhanced technology and information sharing, to harass or discredit civic space actors with nuisance suits, internet crackdowns, and surveillance. [33] For example, Turkmen diplomats have previously accused activists of terrorism, following a series of protests in 2020, [34] and authoritarian governments elsewhere in the region have employed false or inflated drug charges to target activists.

3.2 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced civic actors in Turkmenistan a total of 4 times from January 2015 to March 2021. However, all four instances referenced foreign and intergovernmental civic space actors active in Turkmenistan, rather than domestic Turkmen entities. Russian state media mentioned 2 civic actors by name and 1 informal group operating in Turkmenistan’s civic space. In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of Turkmen citizens, we also analyzed 5 mentions of five keywords in conjunction with Turkmenistan: North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO, the United States, the European Union, democracy, and the West. In this section, we examine Russian state media coverage of civic space actors, how this has evolved over time, and the portrayal of democratic institutions and Western powers to Turkmen audiences.

3.2.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in Turkmenistan’s Civic Space

Russian state media dedicated all mentions of civic space actors in Turkmenistan (4 instances) to external actors. TASS and Sputnik mentioned the intergovernmental International Telecommunication Union (1 mention) and the Russian-owned media outlet Kommersant (1 mention) by name, as well as general mentions of international human rights groups (2 mentions). The international human rights groups were mentioned in reference to their condemnation of the Turkmen government’s actions to dismantle privately owned satellite dishes. Both mentions were neutral in sentiment, as was the single mention of Kommersant. Russian state media covered the International Telecommunication Union “somewhat positively” in the context of improving internet standards in Turkmenistan.

The low number of overall mentions, and the absence of references to domestic civic space actors, is likely a result of the Turkmen government’s strict control over the media, which prevents information about many local civic space events from leaving the country. Additionally, many domestic and external civic space actors are banned from operating within Turkmenistan, greatly reducing events that could be reported on and included in our dataset.

Table 5. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Turkmenistan by Sentiment

|

External Civic Actors |

Neutral |

Somewhat Positive |

Grand Total |

|

International Human Rights Groups |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

International Telecommunication Union |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

Kommersant |

1 |

0 |

1 |

3.2.3 Russian State Media’s Focus on Turkmenistan’s Civic Space over Time

Elsewhere in the E&E region, Russian state media mentions of civic space actors spike around major events and tend to show up in clusters. This is not really the case in Turkmenistan where the number of instances is low and fairly spread out across the period of January 2015 to March 2021. The two mentions of the international human rights groups were in April 2015, coinciding with the launch of Turkmenistan’s first satellite in space. The other two Russian state media mentions of external civic space actors occurred in June 2016, in conjunction with a defense minister meeting, and October 2019, which does not appear to coincide with any key event in Turkmenistan.

It is important to underscore that the lack of coverage of civic space actors operating in Turkmenistan may highlight less about Russian state-owned media, and more about the nature of the Turkmen civic space. The Turkmenistan government does not allow external media outlets to circulate within its borders and takes domestic civic space actors are few in number and limited in their activities due to extensive restrictions in their operation and funding. As such, it is not surprising that Russian state media coverage of Turkmenistan’s civic space is sparse.

Figure 10. Russian State Media Mentions of Turkmen Civic Space Actors

Number of Mentions Recorded

Notes: This figure shows the distribution and concentration of Russian state media mentions of Turkmenistan civic space actors between January 2015 and March 2021. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

3.2.4 Russian State Media Coverage of Western Institutions and Democratic Norms

In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of Turkmen citizens, we analyzed the frequency and sentiment of coverage related to five keywords in conjunction with Turkmenistan. [35] Between January 2015 and March 2021, two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced three of these keywords a total of 5 times with regard to Turkmenistan. This included: the European Union (1 instance), the United States (2 instances), and the “West” (2 instances). No mentions of democracy or the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) were recorded.

Table 6. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

|

Keyword |

Somewhat Negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat Positive |

Grand Total |

|

NATO* |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

European Union |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

United States |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

Democracy* |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

West |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

The “West” received 2 mentions, both in relation to equipment and energy trade. The European Union received only 1 mention, in relation to an international discussion that included representatives from both the European Union and Turkmenistan. Each of these mentions were neutral in tone. The United States received two mentions, 1 “somewhat negative” and 1 “somewhat positive.”

The positive U.S. mention was in regard to Russian state media recognizing the help of U.S. allies during the 72nd anniversary of Victory Day. The negative U.S. reference was in the context of Russian state media coverage of the “Greater Central Asia project,” a former U.S. initiative intended to take a regional approach to addressing security and stability issues across the former Soviet Central Asian republics. [36] Russian state media implied that the U.S. policy was controlling and stated that, “[the Russian government has] been hearing about the United States’ desire to somewhat abuse [the C5+1] format and promote the ideas related to what was called the Greater Central Asia project under the previous administrations.” [37]

Both of these U.S. mentions are indicative of larger narratives observed in Russian state media coverage across the broader E&E region. The negative mention portrays U.S. involvement in the region as controlling and manipulative. The positive mention highlights past military successes as a tool for bolstering national pride. Both narratives aim to bolster Russia’s image domestically and internationally, either by undermining the alternative ideologies of adversaries or promoting nostalgia of Soviet history.

4. Conclusion

The profile of Russia’s engagement with Turkmenistan is decidedly different from that observed elsewhere in the E&E region. Rather than the usual emphasis on compatriot unions and cultural promotion, the Kremlin’s projects in Turkmenistan squarely focused on government counterparts and promoting bilateral security cooperation. Similarly, there was limited Russian state-run media mentions related to civic space actors.

This status quo likely reflects the Kremlin's calculation that it will get farther in advancing its regional ambitions through cultivating Turkmenistan's chief executive than in engaging with the relatively few formal civil society organizations operating in the country. Furthermore, this situation underscores that Moscow does not employ a one-size fits all influence playbook and reinforces the benefit of having comparable metrics to monitor its activities across the region to highlight where those differences lie.

We hope that the country reports, regional synthesis, and supporting dataset of civic space indicators produced by this multi-year project is a foundation for future efforts to build upon and incrementally close this critical evidence gap.

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

In this section, we provide a brief overview of the data and methods used in the creation of this country report and the underlying data collection upon which these insights are based. More in-depth information on the data sources, coding, and classification processes for these indicators is available in our full technical methodology available on aiddata.org.

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

AidData collected and classified unstructured information on instances of harassment or violence, restrictive legislation, and state-backed legal cases from two primary sources: (i) CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Turkmenistan; and (ii) Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. AidData supplemented this data with country-specific information sources from media associations and civil society organizations who report on such restrictions.

Restrictions that took place prior to January 1, 2017 or after March 31, 2021 were excluded from data collection. It should be noted that there may be delays in reporting of civic space restrictions. More information on the coding and classification process is available in the full technical methodology documentation.

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

Due to the extremely restrictive environment of Turkmenistan, the World Values Survey was not conducted for either of the two most recent waves of the survey: WVS Wave 6 in 2011 or WVS Wave 7 in 2017-2021. Therefore, we were unable to draw on these sources to examine citizens’ interest in politics, participation in political action or voluntary organizations, and confidence in institutions.

The Central Asia Barometer Wave 4 was conducted in Turkmenistan in November 2018, with 1500 random, nationally representative respondents aged 18 and up. Wave5 was conducted in Turkmenistan between April and May 2019, with 1500 random, nationally representative respondents aged 18 and up. The Central Asia Barometer trust indicator uses the question “In general, how strongly do you trust or distrust (Insert Item) media? Would you say you…” with respondents provided the following choices: “Strongly trust,” “Trust somewhat,” “Distrust somewhat,” “Strongly distrust,” “Refused,” and “Don’t Know/Not sure” for Television, Newspaper, and the Radio [38] .

The Gallup World Poll was conducted annually in the E&E region countries from 2009-2020, except for the countries that did not complete fieldwork due to the coronavirus pandemic. Each country sample includes at least 1,000 adults and is stratified by population size and/or geography with clustering via one or more stages of sampling. The data are weighted to be nationally representative. In Turkmenistan, however, there is no Gallup data for 2009, 2010, 2020, or 2021.

The Civic Engagement Index is an estimate of citizens’ willingness to support others in their community. It is calculated from positive answers to three questions: “Have you done any of the following in the past month? How about donated money to a charity? How about volunteered your time to an organization? How about helped a stranger or someone you didn’t know who needed help?”

The engagement index is then calculated at the individual level, giving 33% to each of the answers that received a positive response. Turkmenistan’s country values are then calculated from the weighted average of each of these individual Civic Engagement Index scores. The regional mean is similarly calculated from the weighted average of each of those Civic Engagement Index scores, taking the average across all 17 E&E countries: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. The regional means for 2020 and 2021 are the exception, as Gallup World Poll fieldwork was not conducted for Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, and Turkmenistan in 2020, and data is only available for Ukraine and Serbia for 2021.

5.3 Russian Projectized Support to Civic Space Actors or Regulators

AidData collected and classified unstructured information on instances of Russian financing and assistance to civic space identified in articles from the Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones between January 1, 2015 and August 31, 2021. Queries for Factiva Analytics pull together a collection of terms related to mechanisms of support (e.g., grants, joint training, etc.), recipient organizations, and concrete links to Russian government or government-backed organizations. In addition to global news, we reviewed a number of sources specific to each of the 17 target countries to broaden our search and, where possible, confirm reports from news sources.

While many instances of Russian support to civic society or institutional development are reported with monetary values, a greater portion of instances only identified support provided in-kind, through modes of cooperation, or through technical assistance (e.g., training, capacity building activities). In the initial phase of inquiry, these will be recorded as such without a monetary valuation. More information on the coding and classification process is available in the full technical methodology documentation.

5.4 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

AidData developed queries to isolate and classify articles from three Russian state-owned media outlets (TASS, Russia Today, and Sputnik) using the Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Articles published prior to January 1, 2015 or after March 31, 2021 were excluded from data collection. These queries identified articles relevant to civic space, from which AidData, during an initial round of pilot coding, was able to record mentions of formal or informal civic space actors operating in Turkmenistan. It should be noted that there may be delays in reporting of relevant news.

Each identified mention of a civic space actor was assigned a sentiment according to a five-point scale: extremely negative, somewhat negative, neutral, somewhat positive, and extremely positive. These numbers and the sentiment distribution are subject to change as AidData refines its methodology. More information on the coding and classification process is available in the full technical methodology documentation.

[1] The 17 countries include Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

[2] The specific time period varies by year, country, and indicator, based upon data availability.

[3] This definition includes formal civil society organizations and a broader set of informal civic actors, such as political opposition, media, other community groups (e.g., religious groups, trade unions, rights-based groups), and individual activists or advocates. Given the difficulty to register and operate as official civil society organizations in many countries, this definition allows us to capture and report on a greater diversity of activity that better reflects the environment for civic space. We include all these actors in our indicators, disaggregating results when possible.

[4] Much like with other cases of abuse, assault, and violence against individuals, where victims may fear retribution or embarrassment, we anticipate that this number may understate the true extent of restrictions.

[5] Turkmenistan Attacks the Credibility of Independent News Sources and Locks Up Critics. CIVICUS Monitor News. 27 August 2019.

[6] Government Responds to COVID-19 and Hurricane with Denial, Cover-Ups and Intimidation Tactics. CIVICUS Monitor News. 8 June 2020

[7] Other political parties were allowed to be founded after 2012 in order to give the appearance of a multi-party system.

[8] Weekly Digest of Central Asia. The Times of Central Asia. 16 December 2017, via Factiva.

[9] Due to the extremely restrictive environment of Turkmenistan, the World Values Survey was not conducted for either of the two most recent waves of the survey: WVS Wave 6 in 2011 or WVS Wave 7 in 2017–2021. Therefore, we were unable to draw on these sources to examine citizens’ interest in politics, participation in political action or voluntary organizations, and confidence in institutions.

[10] While these questions do not distinguish between specific media outlets, they serve as a useful indicator of how Turkmen citizens receive and process the news in general.

[11] On CAB Wave 5, Kazakhstan averaged 58 percent trust (both “Strong” and “Somewhat”) across all three types of media, Tajikistan averaged 75 percent trust, and Uzbekistan averaged 79 percent trust.

[12] A free and independent media is related to citizens’ trust of the information it publishes, but one may not necessarily be a precondition for the other. Turkmenistan has no media independence. Indeed, Freedom House’s 2018 Freedom in the World report notes that Turkmenistan's media is controlled by the state and used “to advance the regime’s propaganda and consolidate the president’s personality cult.” https://freedomhouse.org/country/turkmenistan/nations-transit/2018

[13] The GWP Civic Engagement Index is calculated at an individual level, with 33% given for each of three civic-related activities (Have you: Donated money to charity? Volunteered your time to an organization in the past month?, Helped a stranger or someone you didn't know in the past month?) that received a “yes” answer. The country values are then calculated from the weighted average of these individual Civic Engagement Index scores.

[14] The regional mean is generally calculated from the index values of Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, the Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. For further information, see the technical annex.

[15] Citizens’ reported rates of volunteering dropped 32 percentage points (to 21 percent) in 2014 from the previous year, while the share who reported helping a stranger dropped by 11 percentage points (to 45 percent). Counterintuitively, citizens gave money to charity more frequently in face of the stresses caused by subsidy cuts (+12 percentage points).

[16] https://freedomhouse.org/country/turkmenistan/nations-transit/2015

[17] In 2015, Turkmenistan improved 16 points on the Civic Engagement Index from the previous year, with gains in citizens contributing to charity (+6 percentage points), volunteering (+39 percentage points), and helping strangers (+4 percentage points).

[18] https://freedomhouse.org/country/turkmenistan/nations-transit/2015

[19] Though fewer than one in four Turkmen respondents reported volunteering their time in 2019.

[20] Particularly the provisions included in the 2017 Amendments to Article 29 of the PA Law, which exclude “foreign budget organizations” from funding organizations. Source: https://www.icnl.org/resources/civic-freedom-monitor/turkmenistan

[21] https://www.facebook.com/people/Россотрудничество-Туркменистан-Rossotrudnichestvo-Turkmenistan/100067550116969/

[22] https://turkmenportal.com/blog/39378/otkryta-registraciya-na-besplatnoe-obuchenie-inostrancev-v-rossii-v-20222023-uchebnom-godu

[23] https://turkmenportal.com/en/blog/32022/the-representative-office-of-rossotrudnichestvo-in-turkmenistan-holds-a-creative-competition

[24] https://usa.tmembassy.gov.tm/en/news/13575

[25] Though President Putin originally signed a version of the cooperation agreement in April 2003 with then Turkmen President Saparmurat Niyazovthe it then stalled out for 17 years as Turkmenistan sought independence from Moscow’s orbit. https://central.asia-news.com/en_GB/articles/cnmi_ca/features/2020/11/12/feature-01

[26] http://en.kremlin.ru/catalog/keywords/78/events/copy/64364

[27] Interestingly, while Russian agencies have supported dozens of sports-related events throughout the region, the Kremlin did not opt to engage with Turkmenistan’s many sports associations, instead focusing on the President and the decision-makers closest to him.

[28] CIVICUS, Joint Submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review 30th Session of the UPR Working Group: https://www.civicus.org/documents/Turkmenistan.CIVICUS.UPRSubmisson2017.pdf

[29] https://freedomhouse.org/country/turkmenistan/freedom-world/2021

[30] https://central.asia-news.com/en_GB/articles/cnmi_ca/features/2020/11/12/feature-01

[31] http://kremlin.ru/supplement/1661

[32] http://kremlin.ru/supplement/1661

[33] For example, Human Rights Watch has criticized the Turkmen government’s past attempts to build its cyber security capacity as enabling more total internet crackdowns and surveillance of civic space actors. https://en.hronikatm.com/2018/02/the-president-of-turkmenistan-meets-a-representative-of-the-company-specializing-in-state-security-and-surveillance-systems/ ; https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/06/25/turkmenistan-report-inquiry-german-cybersecurity-firm#

[34] https://freedomhouse.org/country/turkmenistan/nations-transit/2021

[35] These keywords included North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO, the United States, the European Union, democracy, and the West

[36] Indeo, Fabio. “The Concept of a "Greater Central Asia: Perspectives of a Regional Approach.” Central Asian Studies Institute. October 2011. https://auca.kg/uploads/CASI/Working_Papers/WP_Indeo.pdf.

[37] “Lavrov points to US’ desire to misuse C5+1 format in Central Asia.” ITAR-TASS. Published January 15, 2018.

[38] For full documentation of Central Asia Barometer survey waves, see: https://ca-barometer.org/en/cab-database