North Macedonia: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence

Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, Lincoln Zaleski

April 2023

[Skip to Table of Contents] [Skip to Chapter 1]Executive Summary

This report surfaces insights about the health of North Macedonia’s civic space and vulnerability to malign foreign influence in the lead up to Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Research included extensive original data collection to track Russian state-backed financing and in-kind assistance to civil society groups and regulators, media coverage targeting foreign publics, and indicators to assess domestic attitudes to civic participation and restrictions of civic space actors. Crucially, this report underscores that the Kremlin’s influence operations were not limited to Ukraine alone and illustrates its use of civilian tools in North Macedonia to co-opt support and deter resistance to its regional ambitions.

The analysis was part of a broader three-year initiative by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to produce quantifiable indicators to monitor civic space resilience in the face of Kremlin influence operations over time (from 2010 to 2021) and across 17 countries and 7 occupied or autonomous territories in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). Below we summarize the top-line findings from our indicators on the domestic enabling environment for civic space in North Macedonia, as well as channels of Russian malign influence operations:

- Restrictions of Civic Actors : North Macedonian civic space actors were the targets of 173 restrictions between January 2015 and March 2021, including harassment or violence (81 percent), state-backed legal cases (11 percent), and restrictive legislation (8 percent). Fifty-three percent of cases occurred in 2015 and 2016, coinciding with a massive illegal surveillance operation coming to light and ending the ten-year reign of the VMRO-DPMNE party. Journalists were most frequently targeted, and the North Macedonian government was the primary initiator. Foreign governments were involved in three instances of restriction, including: Serbia (2), Bulgaria (1), and Russia (1).

- Attitudes Towards Civic Participation : Only one-third of North Macedonians were interested in politics in 2019. Citizens increasingly felt unable to impact government decisions and concerned about reprisals if they did engage politically. Nevertheless, North Macedonians had a stronger appetite to engage in less political forms of civic participation, reporting higher rates of activity and membership in voluntary organizations than regional peers. In 2021, North Macedonia surpassed the regional average in its civic participation, with strong showings in the share of citizens donating to charity (51 percent) and helping strangers (69 percent).

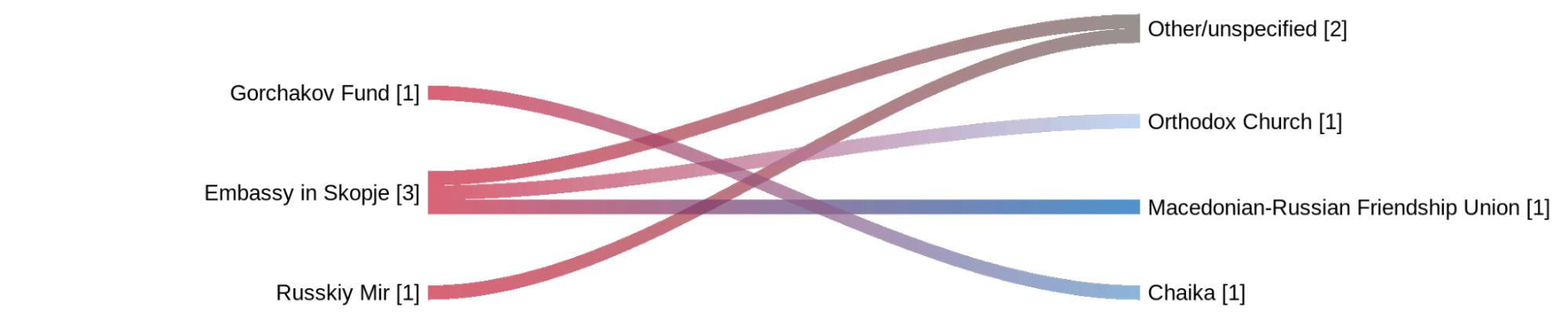

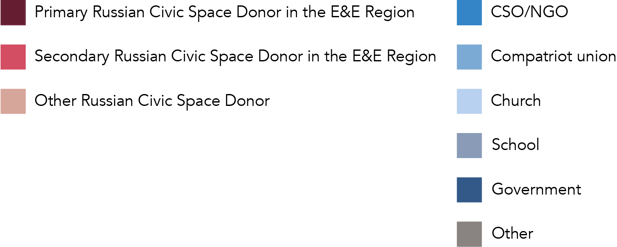

- Russian-backed Civic Space Projects : The Kremlin supported 2 North Macedonian entities via 3 civic space-relevant projects between January 2015 and August 2021. Promoting Russian-Macedonian friendship by highlighting shared history and strengthening Eastern Orthodox religious ties were the primary areas of focus. The Russian government routed its engagement in North Macedonia through three state channels: the Gorchakov Fund, Russkiy Mir Foundation, and the Russian embassy in Skopje. Macedonian recipient organizations were relatively more established than those the Kremlin typically engages with elsewhere in the region and included: the Union of Macedonian-Russian Friendship Societies, the Society of Russian Compatriots “Chaika,” and the Macedonian Orthodox Church.

- Russian State-run Media : Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News referenced North Macedonian civic actors 196 times from January 2015 to March 2021. Political parties were the most frequently mentioned domestic actors. Russian media used its coverage of civic space actors to emphasize inter-ethnic strife, criticize pro-European parties, and promote pro-Kremlin voices. The Kremlin wielded its state media in the earlier years to discourage North Macedonia’s accession to NATO, with mentions tapering off later in the period after that window of opportunity had passed.

Table of Contents

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in North Macedonia

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in North Macedonia: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

2.2 Attitudes Toward Civic Space in North Macedonia

2.2.1 Interest in Politics and Willingness to Act as Barometers of North Macedonian Civic Space

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to North Macedonia’s Civic Space

3.1.1 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to North Macedonia’s Civic Space

3.1.2 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to North Macedonia's Civic Space

3.2 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

3.2.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic North Macedonian Civic Space Actors

3.2.2 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in North Macedonian Civic Space

3.2.3 Russian State Media’s Focus on North Macedonia’s Civic Space over Time

3.2.4 Russian State Media Coverage of Western Institutions and Democratic Norms

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

5.3 Russian Projectized Support to Civic Space Actors or Regulators

5.4 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

Figures and Tables

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of North Macedonian Civic Space Actors

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in North Macedonia

Figure 2. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in North Macedonia

Figure 3. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in North Macedonia by Initiator

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in North Macedonia

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in North Macedonia

Figure 8. Political Action: North Macedonian Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2019

Figure 9. Interest in Politics: North Macedonian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2019

Figure 10. Political Action: Participation by North Macedonian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2019

Figure 11. Voluntary Organization Membership: North Macedonian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2019

Table 5. North Macedonian Confidence in Key Institutions versus Regional Peers, 2019

Figure 12. Civic Engagement Index: North Macedonia versus Regional Peers

Figure 13. Russian Projects Supporting North Macedonian Civic Space Actors by Type

Figure 14. Kremlin-affiliated Support to North Macedonian Civic Space

Figure 15. Locations of Russian Support to North Macedonian Civic Space

Table 6. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in North Macedonia by Sentiment

Table 7. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in North Macedonia by Sentiment

Figure 16. Russian State Media Mentions of North Macedonian Civic Space Actors

Figure 17. Keyword Mentions by Russian State Media in Relation to North Macedonia

Table 8. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, and Lincoln Zaleski. John Custer, Sariah Harmer, Parker Kim, and Sarina Patterson contributed editing, formatting, and supporting visuals. Kelsey Marshall and our research assistants provided invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report including: Jacob Barth, Kevin Bloodworth, Callie Booth, Catherine Brady, Temujin Bullock, Lucy Clement, Jeffrey Crittenden, Emma Freiling, Cassidy Grayson, Annabelle Guberman, Sariah Harmer, Hayley Hubbard, Hanna Kendrick, Kate Kliment, Deborah Kornblut, Aleksander Kuzmenchuk, Amelia Larson, Mallory Milestone, Alyssa Nekritz, Megan O’Connor, Tarra Olfat, Olivia Olson, Caroline Prout, Hannah Ray, Georgiana Reece, Patrick Schroeder, Samuel Specht, Andrew Tanner, Brianna Vetter, Kathryn Webb, Katrine Westgaard, Emma Williams, and Rachel Zaslavsk. The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

This research was made possible with funding from USAID's Europe & Eurasia (E&E) Bureau via a USAID/DDI/ITR Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) cooperative agreement (AID-A-12-00096). The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

A Note on Vocabulary

The authors recognize the challenge of writing about contexts with ongoing hot and/or frozen conflicts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consistently label groups of people and places for the sake of data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that terminology is political, but our use of terms should not be construed to mean support for one faction over another. For example, when we talk about an occupied territory, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the government in the capital. Or, when we analyze the de facto authorities’ use of legislation or the courts to restrict civic action, it is not to grant legitimacy to the laws or courts of separatists, but rather to glean meaningful insights about the ways in which institutions are co-opted or employed to constrain civic freedoms.

Citation

Custer, S., Mathew, D., Burgess, B., Dumont, E., Zaleski, L. (2023). North Macedonia: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence . April 2023. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William and Mary.

1. Introduction

How strong or weak is the domestic enabling environment for civic space in North Macedonia? To what extent do we see Russia attempting to shape civic space attitudes and constraints in North Macedonia to advance its broader regional ambitions? Over the last three years, AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—has collected and analyzed vast amounts of historical data on civic space and Russian influence across 17 countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). [1] In this country report, we present top-line findings specific to North Macedonia from a novel dataset which monitors four barometers of civic space in the E&E region from 2010 to 2021 (see Table 1). [2]

For the purpose of this project, we define civic space as: the formal laws, informal norms, and societal attitudes which enable individuals and organizations to assemble peacefully, express their views, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. [3] Here we provide only a brief introduction to the indicators monitored in this and other country reports. However, a more extensive methodology document is available via aiddata.org which includes greater detail about how we conceptualized civic space and operationalized the collection of indicators by country and year.

Civic space is a dynamic rather than static concept. The ability of individuals and organizations to assemble, speak, and act is vulnerable to changes in the formal laws, informal norms, and broader societal attitudes that can facilitate an opening or closing of the practical space in which they have to maneuver. To assess the enabling environment for North Macedonian civic space, we examined two indicators: restrictions of civic space actors (section 2.1) and citizen attitudes towards civic space (section 2.2). Because the health of civic space is not strictly a function of domestic dynamics alone, we also examined two channels by which the Kremlin could exert external influence to dilute democratic norms or otherwise skew civic space throughout the E&E region. These channels are Russian state-backed financing and in-kind support to government regulators or pro-Kremlin civic space actors (section 3.1) and Russian state-run media mentions related to civic space actors or democracy (section 3.2).

Since restrictions can take various forms, we focus here on three common channels which can effectively deter or penalize civic participation: (i) harassment or violence initiated by state or non-state actors; (ii) the proposal or passage of restrictive legislation or executive branch policies; and (iii) state-backed legal cases brought against civic actors. Citizen attitudes towards political and apolitical forms of participation provide another important barometer of the practical room that people feel they have to engage in collective action related to common causes and interests or express views publicly. In this research, we monitored responses to citizen surveys related to: (i) interest in politics; (ii) past participation and future openness to political action (e.g., petitions, boycotts, strikes, protests); (iii) trust or confidence in public institutions; (iv) membership in voluntary organizations; and (v) past participation in less political forms of civic action (e.g., donating, volunteering, helping strangers).

In this project, we also tracked financing and in-kind support from Kremlin-affiliated agencies to: (i) build the capacity of those that regulate the activities of civic space actors (e.g., government entities at national or local levels, as well as in occupied or autonomous territories ); and (ii) co-opt the activities of civil society actors within E&E countries in ways that seek to promote or legitimize Russian policies abroad. Since E&E countries are exposed to a high concentration of Russian state-run media, we analyzed how the Kremlin may use its coverage to influence public attitudes about civic space actors (formal organizations and informal groups), as well as public discourse pertaining to democratic norms or rivals in the eyes of citizens.

Although Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine February 2022 undeniably altered the civic space landscape in North Macedonia and the broader E&E region for years to come, the historical information in this report is still useful in three respects. By taking the long view, this report sheds light on the Kremlin’s patient investment in hybrid tactics to foment unrest, co-opt narratives, demonize opponents, and cultivate sympathizers in target populations as a pretext or enabler for military action. Second, the comparative nature of these indicators lends itself to assessing similarities and differences in how the Kremlin operates across countries in the region. Third, by examining domestic and external factors in tandem, this report provides a holistic view of how to support resilient societies in the face of autocratizing forces at home and malign influence from abroad.

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

|

Civic Space Barometer |

Supporting Indicators |

|

Restrictions of civic space actors (January 2015–March 2021) |

|

|

Citizen attitudes toward civic space (2010–2021)

|

|

|

Russian projectized support relevant to civic space (January 2015–August 2021) |

|

|

Russian state media mentions of civic space actors (January 2015–March 2021) |

|

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in North Macedonia

A healthy civic space is one in which individuals and groups can assemble peacefully, express views and opinions, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. Laws, rules, and policies are critical to this space, in terms of rights on the books (de jure) and how these rights are safeguarded in practice (de facto). Informal norms and societal attitudes are also important, as countries with a deep cultural tradition that emphasizes civic participation can embolden civil society actors to operate even absent explicit legal protections. Finally, the ability of civil society actors to engage in activities without fear of retribution (e.g., loss of personal freedom, organizational position, and public status) or restriction (e.g ., constraints on their ability to organize, resource, and operate) is critical to the practical room they have to conduct their activities. If fear of retribution and the likelihood of restriction are high, this has a chilling effect on the motivation of citizens to form and participate in civic groups.

In this section, we assess the health of civic space in North Macedonia over time in two respects: the volume and nature of restrictions against civic space actors (section 2.1) and the degree to which North Macedonians engage in a range of political and apolitical forms of civic life (section 2.2).

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in North Macedonia: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time

North Macedonian civic space actors experienced 173 known restrictions between January 2015 and March 2021 (see Table 2). These restrictions were weighted toward instances of harassment or violence (81 percent). There were fewer instances of state-backed legal cases (11 percent) and newly proposed or implemented restrictive legislation (8 percent); however, these instances can have a multiplier effect in creating a legal mandate for a government to pursue other forms of restriction. These imperfect estimates are based upon publicly available information either reported by the targets of restrictions, documented by a third-party actor, or covered in the news (see Section 5). [4]

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of North Macedonian Civic Space Actors

|

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021-Q1 |

Total |

|

Harassment/Violence |

31 |

38 |

31 |

17 |

6 |

14 |

3 |

140 |

|

Restrictive Legislation |

3 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

14 |

|

State-backed Legal Cases |

10 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

19 |

|

Total |

44 |

48 |

32 |

19 |

7 |

20 |

3 |

173 |

Instances of restrictions of North Macedonia civic space actors were unevenly distributed across the time period and spiked in 2015 and 2016, with three restrictions recorded in the first quarter of 2021 (Figure 1). Fifty-three percent of cases were recorded in 2015 and 2016 alone, coinciding with a massive illegal surveillance operation of over 20,000 individuals by the government coming to light and, eventually, ending the ten-year reign of the VMRO-DPMNE party. Journalists and other members of the media were the most frequent targets of violence and harassment, appearing in 51 percent of all recorded instances (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in North Macedonia

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment/Violence

Restrictive Legislation

State-backed Legal Cases

Key Events Relevant to Civic Space in North Macedonia

|

January 2015 |

Zoran Zaev, opposition leader, is charged with conspiring to overthrow the government in the wiretap case. He claims to expose the government's criminal activity. |

|

May 2015 |

Clashes in Kumanovo leave 8 police and 14 gunmen dead. The government blames the unrest on ethnic Albanians from Kosovo. |

|

April 2016 |

Despite protests, President Gjorge Ivanov upholds his pardon of 56 officials investigated over the massive wiretapping scandal. |

|

December 2016 |

Macedonians vote in a general election, called two years early, to end a paralyzing political crisis. |

|

April 2017 |

Protesters storm parliament over the election of an ethnic Albanian, Talat Xhaferi, as Speaker. The interior minister resigns the next day. |

|

December 2017 |

A court places three opposition MPs in judicial custody and another three under house arrest over the attack on parliament in April. |

|

May 2018 |

A Skopje criminal court clears PM Zoran Zaev on bribery charges dating back to his mayorship of Strumica. |

|

July 2018 |

NATO invites Macedonia to join, post-implementation of the name-change deal signed with Greece. Russia accuses NATO of bringing Macedonia into the alliance by force. |

|

November 2018 |

Former premier Nikola Gruevski, who fled to Budapest after being convicted for abuse of power, is granted asylum by Hungary. |

|

February 2019 |

Macedonia's new name, North Macedonia, comes into force, and both Greece and North Macedonia inform the UN of the change. |

|

October 2019 |

EU leaders block talks with North Macedonia, despite concerns over increasing Chinese and Russian influence in the Balkans. |

|

March 2020 |

The EU determines North Macedonia merits accession negotiations. North Macedonia signs an accession document to become NATO's next member. |

|

July 2020 |

The pro-Western SDSM party starts power-sharing negotiations, after narrowly winning an election postponed by COVID-19. |

|

November 2020 |

Around 2,000 demonstrators, led by the opposition VMRO-DPMNE party, gather in anti-government protests calling for the resignation of Prime Minister Zoran Zaev. |

Figure 2. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in North Macedonia

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

The North Macedonian government was the most prolific initiator of restrictions of civic space actors, accounting for 79 recorded mentions. The police were most frequently the channel of restrictions of civic space actors, though politicians and bureaucrats were also initiators of hostility including verbal attacks and threats (Figure 3). Domestic non-governmental actors were identified as initiators in 42 restrictions and there were many incidents involving unidentified assailants (30 mentions). By virtue of the way that the state-backed legal cases indicator was defined, the initiators are either explicitly government agencies and government officials or clearly associated with these actors (e.g., the spouse or immediate family member of a sitting official).

Figure 3. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in North Macedonia by Initiator

Number of Instances Recorded

There were three recorded instances of restrictions of civic space actors during this period involving three foreign governments:

- In May 2016, Zoran Bozinovski, the author of a blog critical of the North Macedonian administration, was detained in Serbia and extradited to Skopje. He was immediately detained for alleged espionage, blackmail, and criminal activity. Various journalists’ associations and unions insist the arrest was politically motivated.

- In June 2016, the North Macedonian President reportedly sought information from Serbian and Bulgarian intelligence services on the activities of “dangerous” North Macedonian CSOs and activists after the “Colorful Revolution.”

- In September 2018, following NATO’s invitation to North Macedonia to join the alliance, the Kremlin flooded Twitter and Facebook with thousands of accounts using the hashtag “#Bojkotiram” (boycott) in an apparent bid to depress turnout at the referendum on joining NATO to less than 50 percent, which would challenge its legitimacy.

Figure 4 breaks down the targets of restrictions by political ideology or affiliation in the following categories: pro-democracy, pro-Western, and anti-Kremlin. [5] Pro-democracy organizations and activists were mentioned 92 times as targets of restriction during this period. [6] Pro-Western organizations and activists were mentioned 38 times as targets of restrictions. [7] There were 3 instances where we identified the target organizations or individuals to be explicitly anti-Kremlin in their public views. [8] It should be noted that this classification does not imply that these groups were targeted because of their political ideology or affiliation, merely that they met certain predefined characteristics. In fact, these tags were deliberately defined narrowly such that they focus on only a limited set of attributes about the organizations and individuals in question.

Figure 4. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in North Macedonia by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment / Violence

Restrictive Legislation

State-backed Legal Cases

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

Instances of harassment (7 threatened, 83 acted upon) towards civic space actors were more common than episodes of outright physical harm (11 threatened, 39 acted upon) during the period. The vast majority of these restrictions (87 percent) were acted on, rather than merely threatened. However, since this data is collected on the basis of reported incidents, this likely understates threats which are less visible (see Figure 5). Of the 140 instances of harassment and violence, acted-on harassment accounted for the largest percentage (59 percent).

Figure 5. Threatened versus Acted-on Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in North Macedonia

Number of Instances Recorded

Recorded instances of restrictive legislation (14) in North Macedonia are important to capture as they give government actors a mandate to constrain civic space with long-term cascading effects. This indicator is limited to a subset of parliamentary laws, chief executive decrees or other formal executive branch policies and rules that may have a deleterious effect on civic space actors, either subgroups or in general. Both proposed and passed restrictions qualify for inclusion, but we focus exclusively on new and negative developments in laws or rules affecting civic space actors. We exclude discussion of pre-existing laws and rules or those that constitute an improvement for civic space.

Several illustrative examples of restrictive legislation employed by the government include:

- Three instances of restrictive legislation were directly related to the release of tapes which exposed criminal activity involving the government. In October 2015, the government drafted and introduced legislation that prohibited the release and republication of material collected during the government’s illegal surveillance operation against civic space actors [9] . The Law on Protection of Whistleblowers came into effect in March 2016 but was criticized for the lack of safeguards it offered to those who came forward to expose government corruption. The ruling coalition passed the Law on Protection of Privacy through an expedited legislative process in May 2016. The legislation prohibited the possession, processing and publishing of any material, including wiretapped conversations, that violated the privacy of a person or family. These three instances, along with other legislation that restricted political advertising and interfered with media freedom, left civic actors vulnerable to manipulation and control by the state.

- Other legislation that curbed civic space included amendments to the Law on Public Gatherings and proposed changes to the Law on Personal Income, which raised concern among members of civil society as it would negatively affect their work. These two proposals were put forward in November 2018 and November 2019, respectively, coinciding with a prolonged period of protests and unrest, as North Macedonia navigated an official change in the country’s name as well as bids for NATO and EU membership.

Civic space actors were the targets of 19 recorded instances of state-backed legal cases between January 2015 and March 2021. Members of the political opposition were most frequently the defendants (Table 3). As shown in Figure 6, charges in these cases were often directly (63 percent) tied to fundamental freedoms (e.g., freedom of speech, assembly). There were some indirect charges (37 percent) such as drug trafficking or bribery, often used by regimes throughout the E&E region to discredit the reputations of civic space actors.

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in North Macedonia

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

|

Defendant Category |

Number of Cases |

|

Media/Journalist |

4 |

|

Political Opposition |

9 |

|

Formal CSO/NGO |

1 |

|

Individual Activist/Advocate |

5 |

|

Other Community Group |

0 |

|

Other |

0 |

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in North Macedonia

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

2.2 Attitudes Toward Civic Space in North Macedonia

The majority of North Macedonian citizens reported low interest in politics on the most recent wave of the World Values Survey / European Values Study, [10] while respondents to the Balkan Barometers survey reported decreased participation in certain forms of political activity (like protests, public debates, comments on social media and discussions with friends) between 2016 and 2019. This coincided with an uptick in citizens reporting they felt unable to impact government decisions. Compared to its regional peers, however, North Macedonia’s civic space appears more robust, with higher rates of activity and membership in voluntary organizations reported in 2019. Lingering fears of reprisal and a general discontent with the “political” sphere appear to be the main impediments to citizens’ active participation in the civic space, as reported in the Balkan Barometer surveys.

In this section, we take a closer look at North Macedonian citizens’ interest in politics, participation in political action or voluntary organizations, and confidence in institutions. We also examine how North Macedonian involvement in less political forms of civic engagement—donating to charities, volunteering for organizations, helping strangers—has evolved over time.

2.2.1 Interest in Politics and Willingness to Act as Barometers of North Macedonian Civic Space

Forty percent of North Macedonian respondents in the 2016 Balkan Barometer survey indicated that their political activity was limited to discussing issues with friends, rather than more public-facing activities including protests and commenting on social networking sites (8 percent, each). Public debates were the least popular mode of political participation among North Macedonians in 2016, with only a small fraction of respondents indicating that they joined these discussions (3 percent).

In 2019, approximately one-third of North Macedonians reported being interested in politics. According to the 2019 Balkan Barometer survey, the proportion of respondents who did not even discuss political issues with friends (arguably the least risky form of political participation in the survey) rose from one-third in 2016 to nearly fifty percent in 2019 (Figure 7). The share of respondents who engaged in political conversations on social media increased, but only slightly (+2 percentage points).

Figure 7. Political Action: Participation by North Macedonian Citizens versus Balkan Peers, 2016 and 2019

Percentage of Respondents

The World Values Survey, conducted in North Macedonia in 2019, found higher levels of engagement on a different set of political activities than those included in the Balkan Barometers surveys (Figure 8). One-fifth of respondents had signed a petition, and almost as many reported joining a boycott or demonstration (15 percent and 17 percent, respectively). [11] An additional quarter of respondents indicated that they may take part in these three activities in the future. Nevertheless, a fairly substantial part of society still could not conceive of the possibility of their engaging in these forms of political participation. Over forty percent said they would never join a petition, boycott or demonstration. There was even less appetite for strikes, with 62 percent of respondents unwilling to participate.

North Macedonians’ interest in politics was relatively on par with their peers across the E&E region in 2019 (Figure 9), [12] but were comparatively more likely to have engaged with petitions, boycotts, demonstrations, and strikes by 3 to 9 percentage points (Figure 10). Macedonians were slightly more likely than their Balkan counterparts to have joined in public debates, protests, and commented on social media (+1 to 2 percentage points). [13] They were also less likely than their regional peers (-2 percentage points) to have only discussed issues with friends or to have not discussed issues at all (Figure 7).

Figure 8. Political Action: North Macedonian Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2019

Percentage of Respondents

Figure 9. Interest in Politics: North Macedonian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2019

Percentage of Respondents

Figure 10. Political Action: Participation by North Macedonian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2019

Percentage of Respondents Reporting “Have Done”

North Macedonian respondents in 2019 were more likely than their peers across the E&E region to be members of voluntary organizations (Table 4), except for labor unions (-4 percentage points) and consumer organizations (-1 percentage point). North Macedonians most clearly outstripped other E&E countries (Figure 11) in their involvement in humanitarian or charitable organizations (16 percent), more than double the regional average (6 percent). Compared to regional peers, North Macedonians were more likely to be members of political parties (+5 percentage points), even though their reported confidence in these institutions is low (21 percent) and perceived corruption is high (Table 5). [14]

According to the 2016 and 2019 Balkan Barometer surveys, North Macedonians consistently said that the two biggest deterrents to their involvement in government decision-making were their desire to avoid public exposure and their view that they could not influence government decisions. The share of Macedonians fearing exposure or reprisal if they engaged politically exceeded the regional mean in both survey waves (by +11 and +5 percentage points, respectively). A key shift occurred between the surveys, as the share of Macedonians who believed they could not influence government decisions went from trailing the regional mean (-8 percentage points) in 2016 to exceeding it (+1 percentage point) in 2019.

Figure 11. Voluntary Organization Membership: North Macedonian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2019

Table 4. North Macedonian Citizens’ Membership in Voluntary Organizations by Type versus Regional Peers, 2019

|

Voluntary Organization |

North Macedonian Membership, 2019 |

Regional Mean Membership, 2019 |

Percentage Point Difference |

|

Church or Religious Organization |

14% |

11% |

+3 |

|

Sport or Recreational Organization |

16% |

10% |

+6 |

|

Art, Music or Educational Organization |

13% |

9% |

+5 |

|

Labor Union |

7% |

11% |

-4 |

|

Political Party |

13% |

8% |

+5 |

|

Environmental Organization |

9% |

4% |

+4 |

|

Professional Association |

7% |

5% |

+1 |

|

Humanitarian or Charitable Organization |

16% |

6% |

+10 |

|

Consumer Organization |

2% |

3% |

-1 |

|

Self-Help Group, Mutual Aid Group |

8% |

4% |

+4 |

|

Other Organization |

5% |

4% |

+1 |

Table 5. North Macedonian Confidence in Key Institutions versus Regional Peers, 2019

|

Institution |

North Macedonian confidence, 2019 |

Regional mean confidence, 2019 |

Percentage point difference |

|

Church or Religious Organization |

74% |

68% |

+6 |

|

Military |

64% |

71% |

-8 |

|

Press |

31% |

34% |

-3 |

|

Labor Unions |

25% |

31% |

-6 |

|

Police |

54% |

57% |

-2 |

|

Courts |

34% |

41% |

-7 |

|

Government |

26% |

42% |

-17 |

|

Political Parties |

21% |

26% |

-5 |

|

Parliament |

32% |

36% |

-4 |

|

Civil Service |

38% |

46% |

-7 |

|

Environmental Organizations |

40% |

44% |

-4 |

Declining faith in their ability to impact government decisions appears to mirror the increasing share of Macedonians who reported that they do not even discuss political matters with friends. In parallel, North Macedonians' limited confidence in their government suggests that they believe that affecting political change is either impossible or unlikely to produce meaningful results. Nevertheless, there is some evidence to support the idea that North Macedonians may see greater space (and utility) for engaging in less political forms of civic participation.

Humanitarian and charitable organizations enjoy comparatively high rates of membership and serve as conduits for citizens to gather and address the issues they think are important in their communities. Similar to their Balkan peers, North Macedonians view NGOs as less corrupt (46 percent) than other institutions (67 percent, on average). This perceived trustworthiness may help charitable organizations eschew some of the negative trends of disinterest and pessimism seen elsewhere in North Macedonia’s civic space.

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

The Gallup World Poll’s (GWP) Civic Engagement Index affords an additional perspective on North Macedonia citizens’ attitudes towards less political forms of participation between 2010 and 2021. This index measures the proportion of citizens that reported giving money to charity, volunteering at organizations, and helping a stranger on a scale of 0 to 100. [15] Overall, North Macedonia’s Civic Engagement scores peaked in 2016, retrenched in 2017 and 2018 (Figure 12), before recovering gains later in the period. Charity and helping strangers were the two most important factors driving North Macedonia’s index scores. Unlike other Balkan countries, [16] North Macedonians civic engagement scores do not appear to be correlated with the country’s economic performance, [17] though there are some anecdotal indications that citizens’ appetite for altruism may be somewhat influenced by political trends.

In 2014, North Macedonia had a civic engagement score on par with the regional mean (30 points), but its performance plummeted (-7 percentage points) the next year to 23 points). Volunteerism remained relatively stable, but fewer North Macedonians donated to charity or helped a stranger that year (-8 and -10 percentage points, respectively). Ahead of the 2016 parliamentary elections, North Macedonia’s civic engagement rebounded (+11 points), driven by an uptick in activity across all three index measures. [18] Unfortunately, this improvement was not sustained, as the country’s civic engagement score hovered around 20 points in 2017-18. Notably, this declining civic engagement coincided with the eruption of ethnic tensions in North Macedonia, when years of political tension came to a head and Macedonian nationalists stormed the parliament building. [19]

North Macedonia saw a dramatic improvement in its civic engagement scores beginning in 2019—after the country ratified the Prespa agreement and began its path toward NATO and EU membership [20] —and steadily rising through 2021. [21] North Macedonia’s 2020 index score improved by 10 points compared to the previous year in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 12). By 2021, the country’s index performance overtook the regional mean (+6 percentage point): 51 percent of North Macedonians donated to charity and 69 percent helped a stranger that year, though volunteerism still trailed at 14 percent of respondents. This upward trend is consistent with improving civic engagement across the region and around the world as citizens rallied in response to COVID-19, even in the face of lockdowns and limitations on public gathering. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen as to whether this initial improvement will be sustained in future.

Figure 12. Civic Engagement Index: North Macedonia versus Regional Peers

3. External Channels of Influence: Kremlin Civic Space Projects and Russian State-Run Media in North Macedonia

Foreign governments can wield civilian tools of influence such as money, in-kind support, and state-run media in various ways that disrupt societies far beyond their borders. They may work with the local authorities who design and enforce the prevailing rules of the game that determine the degree to which citizens can organize themselves, give voice to their concerns, and take collective action. Alternatively, they may appeal to popular opinion by promoting narratives that cultivate sympathizers, vilify opponents, or otherwise foment societal unrest. In this section, we analyze data on Kremlin financing and in-kind support to civic space actors or regulators in North Macedonia (section 3.1), as well as Russian state media mentions related to civic space, including specific actors and broader rhetoric about democratic norms and rivals (section 3.2).

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to North Macedonia’s Civic Space

The Kremlin supported 2 known North Macedonian civic organizations via 3 civic space-relevant projects in North Macedonia during the period of January 2015 to August 2021. The composition of these activities indicates that Moscow prefers to directly engage and build relationships with individual civic actors, as opposed to investing in broader based institutional development. The Kremlin’s relationship-building activities were concentrated in the 2016-2018 period (Figure 13) and centered on promoting Russian-Macedonian friendship by highlighting shared history and Eastern Orthodox religious ties.

Figure 13. Russian Projects Supporting North Macedonian Civic Space Actors by Type

Number of Projects Recorded, January 2015–August 2021

The Kremlin routed its engagement in North Macedonia through 3 different channels (Figure 14), which included the Gorchakov Fund (1 project), [22] the language and culture-focused Russkiy Mir Foundation (1 project), and the Russian embassy in Skopje (2 projects). The stated missions of these Russian government entities emphasize education and cultural promotion within a broader public diplomacy strategy. The Gorchakov Fund, which awarded a grant to the Society of Russian Compatriots “Chaika” in February 2018, promotes Russian culture abroad and provides projectized support to non-governmental organizations to bolster Russia’s image. The Russkiy Mir Foundation promotes Russian language education and programming, providing funding to open Russian Centers based in local universities. Russian Embassies frequently support civic space actors as part of their public diplomacy mandate, though often as an auxiliary actor. The Embassy in Skopje funding the opening of a Russkiy Mir branch in January 2016 is one example of this modality.

Rossotrudnichestvo—an autonomous agency under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs which promotes political and economic cooperation abroad—is notably not associated with any of the Kremlin’s overtures to Macedonian civic actors. A leading channel of Russian-backed support throughout the rest of the E&E region, Rossotrudnichestvo does not have a stand-alone Russian Center for Science and Culture in North Macedonia, operating instead out of the Russian Embassy. This coworking arrangement may inhibit one of Rossotrudnichestvo’s go-to modalities of support in other countries: lending physical space and assistance in logistical coordination for events to local civic society actors.

Figure 14. Kremlin-affiliated Support to North Macedonian Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

3.1.1 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to North Macedonia’s Civic Space

Russia supported formal civil society organizations (CSOs), compatriot unions for the Russian diaspora, [23] and Orthodox churches in North Macedonia. These Macedonian recipient organizations were relatively more established than those Russia typically engages with in other countries. [24] The two youngest organizations, the Union of Macedonian-Russian Friendship Societies and the Society of Russian Compatriots “Chaika” were founded in 2013 and 2000, respectively. While domestic government institutions play an important role in maintaining and defining civic space and are a frequent recipient of Kremlin support elsewhere in the region, we did not identify any Macedonian government bodies receiving support relevant to civic space during the period from 2015 to 2021.

Two of the Macedonian recipient organizations work in the education and culture sector with an emphasis on promoting shared Russian-Macedonian history and narratives of shared development. This includes the Society of Russian Compatriots “Chaika,” which received a Gorchakov Fund grant in February 2018 to host the conference titled ‘The contribution of the Russian emigration to the development of the Republic of Macedonia and the Balkan Peninsula in the 20-21 centuries.’ The grant was notable as it highlighted a renewed emphasis on convening Russian compatriots within North Macedonia rather than sending delegates to participate in international conferences. [25]

The Kremlin also appears to wrap religious elements into their cultural events, though less frequently than elsewhere in the E&E region. Religious collaborations in Macedonia were limited to erecting Orthodox crosses and inviting local leaders including the Archbishop of the Macedonian Orthodox Church to the opening of a Russkiy Mir center. In contrast to its overtures in other countries, no Macedonian beneficiaries of Kremlin support were organizations with an explicit emphasis on working with youth. Elsewhere, the Russian Orthodox Church has targeted its activities toward youth, such as its support of military-patriotic boot camps for Belarusian children.

Geographically, Russian-state overtures were primarily oriented towards Skopje (Figure 15). The Society of Russian Compatriots “Chaika” is based in the North Macedonian capital, and the country’s only Russkiy Mir center is based in the Saints Cyril and Methodius University in the city center. Sveti Nikole, a town in the Eastern statistical region, is home to The Union of Macedonian-Russian Friendship Societies. Like “Chaika,” the Union of Macedonian-Russian Friendship Societies is based at a local university: the International Slavic University.

Figure 15. Locations of Russian Support to North Macedonian Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

3.1.2 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to North Macedonia's Civic Space

In a departure from its activities elsewhere in the E&E region, [26] Russian support to civic space actors in North Macedonia appears to be weighted toward direct transfers of funding. Two thirds of the projects explicitly described recipients receiving financial grants—one awarded by the Gorchakov Fund to Chaika, and the other involved the Embassy providing funding to Orthodox churches. There was only one identified instance where the Kremlin provided unspecified non-financial support to the Union of Macedonian-Russian Friendship Societies. Although the Kremlin typically provides event support in the form of venues, materials, or other logistical and technical contributions in other E&E countries, this was not the case in North Macedonia.

More consistent with regional trends was the Kremlin’s emphasis on promoting Russian history, language, and culture—opening the Russkiy Mir center in 2016, supporting a 2018 conference on Russian emigration to Macedonia, and partnering with the Union of Macedonian-Russian Friendship Societies. The Kremlin appears to favor the ethnic Macedonian and the Russian compatriot populations in its overtures, ignoring North Macedonia’s sizable Albanian minority population. In fact, Russia has accused the EU and U.S. of supporting a “Greater Albania” project following the 2016 round of Parliamentary elections, [27] and may seek to exploit anti-Albanian sentiment in the future.

3.2 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced North Macedonian civic actors 196 times from January 2015 to March 2021. Approximately 59 of these mentions (116 instances) were of domestic actors, while the remaining 41 percent (80 instances) focused on foreign and intergovernmental actors operating in North Macedonia’s civic space. In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of North Macedonian citizens, we also analyzed 352 mentions of five keywords in conjunction with North Macedonia: North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO, the United States, the European Union, democracy, and the West. In this section, we examine Russian state media coverage of domestic and external civic space actors, how this has evolved over time, and the portrayal of democratic institutions and Western powers to North Macedonian audiences.

3.2.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic North Macedonian Civic Space Actors

Roughly one-third (35 percent) of Russian media mentions pertaining to domestic actors in North Macedonia’s civic space referred to 14 specific groups by name. They represent a diverse cross-section of organizational types, ranging from political parties to civil society organizations and media outlets. Political parties are the most frequently mentioned domestic organization type (23 mentions), followed by formal civil society organizations (15 mentions). The high number of political party mentions is mostly driven by the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM) with 15 mentions and the Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity (VMRO-DPMNE) with 6 mentions.

Russian state media mentions of specific North Macedonian civic space actors were most often neutral (59 percent) in tone. The remaining coverage was mostly negative (39 percent), with only 1 mention (2 percent) receiving positive coverage. This negative sentiment tended to be strongly held [28] and was directed towards four organizations: the Coalition for Better Macedonia (1 negative mention), the Democratic Union for Integration (1 negative mention), the Movement for a United Macedonia (3 negative mentions), and the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (11 negative mentions).

Through their negative coverage, Russian state media outlets demonstrated two consistent trends in their reporting on North Macedonia: emphasizing inter-ethnic strife and criticizing pro-European parties. For the Democratic Union for Integration (DUI), the largest ethnic Albanian party in North Macedonia, Sputnik’s singular mention stated that the DUI “stubbornly refused to work with the incumbent authorities unless they conceded to the radical demands of the so-called 'Albanian Platform.'” [29] The strong overall negative sentiment, describing the party as “radical,” is similar to Russian state media’s criticism of Albanian organizations in Kosovo and emphasizes ethnic divisions in North Macedonia.

For the pro-European parties, Movement for a United Macedonia and the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM), Russian coverage was predominantly negative. For example, one Sputnik article stated that SDSM “was tasked by the U.S. with being the face of the anti-government movement, and [its] political supporters are characterized by their liberal-progressive beliefs in radical feminism and pro-homosexual legislation.” [30] By characterizing major pro-European parties as “US-controlled” and “radical,” Russian state media seeks to guide readers to viewing pro-Russian parties as more trustworthy.

Aside from these named organizations, TASS and Sputnik made 75 more general references to domestic North Macedonian non-governmental organizations, protesters, opposition activists, and other informal groups during the same period. The sentiment was most often neutral (47 percent) or negative (45 percent). Similar to the named domestic organizations, informal organizations that received negative coverage were largely pro-European or ethnic Albanian actors. The other informal group receiving negative sentiment was the press in Macedonia, as “journalists” and “Macedonian media” were described as “propaganda machinery” and puppets of an American-led color revolution in North Macedonia.

When considering the domestic civic actors as a whole, mentions of protesters and unnamed opposition groups dominate Russian state media headlines (Table 6). The tone of sentiment accorded to the top two most frequently mentioned political parties—the pro-European SDSM and the pro-Russian Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity (VMRO-DPMNE)—is illustrative of a broader trend of Russian state media selectively promoting pro-Kremlin actors with positive coverage and discrediting pro-European actors with negative articles. This distinction is even more pronounced in the coverage of North Macedonia, as compared to other E&E countries, and this divisive rhetoric may stem from North Macedonia’s successful bid to join NATO and its promising campaign to join the EU.

Table 6. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in North Macedonia by Sentiment

|

Domestic Civic Group |

Extremely Negative |

Somewhat Negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat Positive |

Grand Total |

|

Protesters |

6 |

3 |

7 |

2 |

18 |

|

Opposition |

2 |

4 |

10 |

0 |

16 |

|

Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM) |

4 |

7 |

4 |

0 |

15 |

|

Helsinki Committee for Human Rights of the Republic of Macedonia |

0 |

0 |

7 |

0 |

7 |

|

Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity (VMRO-DPMNE) |

0 |

0 |

5 |

1 |

6 |

3.2.2 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in North Macedonian Civic Space

Russian state media dedicated the remaining mentions (80 instances) to external actors in the North Macedonian civic space, including 8 intergovernmental organizations (19 mentions), 22 foreign organizations by name (39 mentions), and 22 general references to 15 foreign actors, such as American NGOs. The majority of external actors mentioned were formal and informal Western organizations, which is reflected in the top mentions of this group (Table 7).

Russian state media mentions of external actors, both named and unnamed, were mostly neutral (55 percent) or negative (40 percent) in tone with only 4 somewhat positive mentions. Negative coverage was heavily concentrated towards Western organizations, as Russian state media accused institutions like the Open Society Foundation, the European Union, and the National Endowment for Democracy, of political manipulation in North Macedonia. Similar to the negative coverage of pro-European domestic actors and Albanian ethnic groups, Russian media deployed conspiracy theories and tenuous accusations to discredit Western institutions working in North Macedonia.

For example, a 2017 TASS article accused Western institutions of using Albanian parties to create discord in North Macedonia saying, “by appointing their puppets, imposing the so-called Tirana platform and other elements of the ‘Greater Albania’ project, which are completely alien to the Macedonian people, the U.S., NATO and the EU are irresponsibly opening up a Pandora’s box.” [31] While Russian accusations of Western influence behind “color revolutions” are prevalent in most E&E countries, the timing of this strong rhetoric in North Macedonia is likely symptomatic of heightened urgency prior to North Macedonia’s accession to NATO membership in March 2020.

Table 7. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in North Macedonia by Sentiment

|

External Civic Actors |

Extremely Negative |

Somewhat Negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat Positive |

Grand Total |

|

Western politicians |

1 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

|

Doctors Without Borders (MSF) |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

4 |

|

European Union |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

|

Human Rights Watch (HRW) |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

4 |

|

Open Society Foundation |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

3.2.3 Russian State Media’s Focus on North Macedonia’s Civic Space over Time

As a general rule, Russian state media mentions of civic space actors tend to spike around specific events within E&E countries. This dynamic is even more pronounced in North Macedonia (Figure 16), as forty-four percent of mentions for the entire tracking period (January 2015–March 2021) occurred in just two months: May 2015 (68 mentions) and April 2017 (18 mentions). These months represent significant events in the life of North Macedonia’s civic space: the 2015 Macedonian anti-government protests during the wiretap scandal and the breaching of Parliament in 2017.

Russian media coverage of the 2015 protests were somewhat more neutral (53 percent), though there were still substantial numbers of negative articles related to the events on the ground (46 percent). Comparatively, coverage of the April 2017 storming of the Macedonian parliament was more stridently negative (78 percent), with only 22 percent neutral mentions. That said, Kremlin-affiliated media took care to blame Western powers for the protest activity and noticeably excluded mentioning the pro-Russian political party VMRO-DPMNE in relation to the event at all.

For example, one TASS article covered the storming of parliament saying, “The protests in Macedonia that culminated when infuriated members of the Coalition for a Better Macedonia broke into parliament building clearly prove the disastrous nature of the policy of protectionism, mentoring and brutal interference in the internal affairs of Macedonia… pursued by the U.S., NATO and the European Union in that region.” [32]

Russian mentions of North Macedonian civic space actors tapered off in the later years of the tracking period, following Greece’s willingness to settle the Macedonia naming dispute and remove a major impediment to the country’s accession to NATO. One interpretation of why this might be the case may have to do with the Kremlin’s assessment that its window of opportunity to discourage North Macedonia’s NATO and EU membership aspirations had passed with the removal of Greece’s veto, reducing the upside for it to continue to expend effort in influencing North Macedonian public opinion to stop this eventuality.

Figure 16. Russian State Media Mentions of North Macedonian Civic Space Actors

Number of Mentions Recorded

3.2.4 Russian State Media Coverage of Western Institutions and Democratic Norms

In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of North Macedonia’s citizens, we analyzed the frequency and sentiment of coverage related to five keywords in conjunction with North Macedonia. [33] Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced all five keywords from January 2015 to March 2021 (Table 8). Russian state media mentioned the European Union (105 instances), the United States (70), NATO (121 instances), the “West” (40 instances), and democracy (17 instances) with reference to North Macedonia during this period.

Sixty-five percent of these mentions (230 instances) were negative, while an extremely small share was positive (4 percent). Similar to civic space actors, the preponderance of Russian state media coverage of the keywords in relation to North Macedonia occurred in the earlier years of the time period, tapering off subsequent to 2019, with only 15 mentions occurring in 2020 and the first quarter of 2021 (Figure 17). This trend may reflect a deprioritization of these topics in Russian media coverage about the country, following North Macedonia’s ascendance into NATO in early 2020.

Figure 17. Keyword Mentions by Russian State Media in Relation to North Macedonia

Number of Unique Keyword Instances of NATO, the U.S., the EU, Democracy, and the West in Russian State Media

Table 8. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

|

Keyword |

Extremely negative |

Somewhat negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat positive |

Extremely positive |

Grand Total |

|

NATO |

16 |

66 |

35 |

4 |

0 |

121 |

|

European Union |

7 |

44 |

49 |

5 |

0 |

105 |

|

United States |

23 |

35 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

70 |

|

Democracy |

0 |

3 |

9 |

5 |

0 |

17 |

|

West |

19 |

17 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

40 |

Russian state media mentioned NATO and the European Union most frequently in reference to North Macedonia. Skopje’s aspirations to join the two membership blocs and the status of accession talks was the most common recurring topic across both keywords. [34] The Kremlin targeted a higher proportion of negative coverage (68 percent of mentions) towards NATO relative to the EU, positioning NATO’s expansion as provoking instability in Europe and as an affront to friendly relations with Russia. Seeking to exploit inter-ethnic tensions, Russian state media portrayed NATO as an “initiator of renewed Albanian insurgency in Kumanovo” [35] which strong-armed Skopje to “embrace the demands of the [country’s] Albanian minority,” [36] emphasizing NATO’s ambition to promote a “Greater Albania,” [37] and recalling NATO’s involvement in the bombing of Yugoslavia. Kremlin-affiliated media questioned the credibility of the Prespa agreement, which resolved a 27-year naming dispute with Greece, and the results of the referendum which established public support for EU and NATO membership. Media coverage routinely cast the costs and risks to North Macedonia of joining NATO as far outweighing the benefits:

“There will certainly be a price to pay for NATO’s protection…In fact, they will have to increase their defense spending, pay for participation in military preparations and operations that have little to do with the interests of the Macedonian people, and also lose the possibility to pursue a truly independent foreign policy'...We don’t see any other security threats and so we ask ourselves: is it possible that NATO will once again wage a war against those who received training and weapons from the Alliance?” [38]

Comparatively, Russian media coverage of the EU in relation to North Macedonia was often neutral (57 percent) and somewhat less negative (49 percent). This slightly more tempered attitude towards the EU, in comparison to NATO, appears to be intentional. For example, one Sputnik article quoted Vladimir Chizhov, Russia’s Permanent Representative to the EU, as suggesting that Macedonia’s accession to NATO would be “a mistake with consequences,” further clarifying that “Russia does not oppose the EU enlargement…but has somewhat of a different stance on NATO.” [39] More negative mentions of the EU accused the membership bloc of colluding with the U.S. and NATO to intervene in North Macedonia’s internal affairs—“instigating a Ukraine-like scenario to remove the government of Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski,” [40] “using the Albanian factor to influence [domestic] events,” [41] and pushing the Prespa agreement to bring about “EuroAtlantic integration…in the Western Balkans.” [42]

Russian state media mentioned the “West” and the United States less frequently in relation to North Macedonia but when they did so, the sentiment was almost entirely negative: 90 and 83 percent negative mentions, respectively. The U.S. attracted negative coverage for its opposition to the Kremlin-backed Turkish Stream gas pipeline, which Russian state media decried as motivated by Washington’s imperial logic” to prevent countries from becoming self-sufficient for “fear of losing control of Europe” [43] and exploiting the Albanian minority to “hinder implementation of [the project]…by fomenting a new conflict in the Balkans.” [44] The Kremlin promoted narratives that the U.S. was exporting “Color Revolution unrest against the government” and “liberal-progressive beliefs…at odds with Macedonia’s conservative majority” with the aim of destabilizing the country. [45] Russian state media used the term “the West” to inject fear about the motives of the U.S. and Europe writ large, warning against “massive propaganda campaigns…to drag Macedonia into NATO” [46] “destructive attempts” to use the Albanian minority to bring the defeated opposition back into power [47] ; and efforts to spread Russophobia. [48]

Of the five keywords, Russian state media was most varied in its coverage of the term “democracy,” which attracted positive mentions (29 percent), along with neutral (53 percent) and negative (18 percent) references. Similar to trends observed elsewhere in the E&E region, these differences in tone convey something of the Kremlin’s intent. Positive coverage of democracy was often used to highlight Western overreach—"it is necessary to stop external interference in the internal affairs of Macedonia, respect Macedonian citizens’ right to decide their own destiny based on the founding democratic principles" [49] —or to talk about Russia’s shared values as a fellow democracy. [50] Meanwhile, negative coverage typically sowed doubt about the Western approach to democracy as “cynical and hypocritical.” [51]

4. Conclusion

The data and analysis in this report reinforces a sobering truth: Russia’s appetite for exerting malign foreign influence abroad is not limited to Ukraine, and its civilian influence tactics are already observable in North Macedonia and elsewhere across the E&E region. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see clearly how the Kremlin invested its media, money, and in-kind support to promote pro-Russian sentiment within North Macedonia and discredit voices wary of its regional ambitions.

The Kremlin was adept in deploying multiple tools of influence in mutually reinforcing ways to amplify the appeal of closer integration with Russia, raise doubts about the motives of the U.S., EU, and NATO, as well as legitimize its actions as necessary to protect the region’s security from the disruptive forces of democracy. Russian state media sought to stoke inter-ethnic cleavages, criticize pro-European parties, and promote pro-Kremlin voices. In parallel, the Kremlin’s cultural and language programming primarily focused on making inroads within Russian compatriots and the Macedonian Orthodox Church. Noticeably, the highest concentration of Kremlin activity occurred in the years prior to North Macedonia’s accession to NATO as Russian authorities sought to forestall this eventuality by stoking skepticism and uncertainty about the alliance. Once the country’s membership was finalized, the Kremlin focused its attention elsewhere.

Taken together, it is more critical than ever to have better information at our fingertips to monitor the health of civic space across countries and over time, reinforce sources of societal resilience, and mitigate risks from autocratizing governments at home and malign influence from abroad. We hope that the country reports, regional synthesis, and supporting dataset of civic space indicators produced by this multi-year project is a foundation for future efforts to build upon and incrementally close this critical evidence gap.

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

In this section, we provide a brief overview of the data and methods used in the creation of this country report and the underlying data collection upon which these insights are based. More in-depth information on the data sources, coding, and classification processes for these indicators is available in our full technical methodology available on aiddata.org.

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

AidData collected and classified unstructured information on instances of harassment or violence, restrictive legislation, and state-backed legal cases from three primary sources: (i) CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for North Macedonia; and (ii) Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. AidData supplemented this data with country-specific information sources from media associations and civil society organizations who report on such restrictions. Restrictions that took place prior to January 1, 2015 or after March 31, 2021 were excluded from data collection. It should be noted that there may be delays in reporting of civic space restrictions. More information on the coding and classification process is available in the full technical methodology documentation.

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

Survey data on citizen perceptions of civic space were collected from three sources: the Joint European Values Study and World Values Survey Wave 2017-2021, the Gallup World Poll (2010-2021), and the Balkan Barometer Waves 2016 and 2019. These surveys capture information across a wide range of social and political indicators. The coverage of the three surveys and the exact questions asked in each country vary slightly, but the overall quality and comparability of the datasets remains high.

The fieldwork for the EVS Wave 7 in North Macedonia was conducted in Macedonian and Albanian between December 2018 and February 2019 with a nationally representative sample of 1117 randomly selected adults residing in private homes, regardless of nationality or language. [52] The research team did not provide an estimated error rate for the survey data after applying a weighting variable “computed using the marginal distribution of age, sex, educational attainment, and region. This weight is provided as a standard version for consistency with previous releases.” [53]

The E&E region countries included in the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 dataset, which were harmonized and designed for interoperable analysis, were Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, and Ukraine. Regional means for the question “How interested have you been in politics over the last 2 years?” were first collapsed from “Very interested,” “Somewhat interested,” “Not very interested,” and “Not at all interested” into the two categories: “Interested” and “Not interested.” Averages for the region were then calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen countries.

Regional means for the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 question “Now I’d like you to look at this card. I’m going to read out some different forms of political action that people can take, and I’d like you to tell me, for each one, whether you have actually done any of these things, whether you might do it or would never, under any circumstances, do it: Signing a petition; Joining in boycotts; Attending lawful demonstrations; Joining unofficial strikes” were calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen E&E countries as well.

The membership indicator uses responses to a Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 question which lists several voluntary organizations (e.g., church or religious organization, political party, environmental group, etc.). Respondents to WVS 7 could select whether they were an “Active member,” “Inactive member,” or “Don’t belong.” The EVS 5 survey only recorded a binary indicator of whether the respondent belonged to or did not belong to an organization. For our analysis purposes, we collapsed the “Active member” and “Inactive member” categories into a single “Member” category, with “Don’t belong” coded to “Not member.” The values included in the profile are weighted in accordance with WVS and EVS recommendations. The regional mean values were calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen countries included in a given survey wave. The values for membership in political parties, humanitarian or charitable organizations, and labor unions are provided without any further calculation, and the “Other community group” cluster was calculated from the mean of membership values in “Art, music or educational organizations,” “Environmental organizations,” “Professional associations,” “Church or other religious organizations,” “Consumer organizations,” “Sport or recreational associations,” “Self-help or mutual aid groups,” and “Other organizations.”

The confidence indicator uses responses to a Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 question which lists several institutions (e.g., church or religious organization, parliament, the courts and the judiciary, the civil service, etc.). Respondents to the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 surveys could select how much confidence they had in each institution from the following choices: “A great deal,” “Quite a lot,” “Not very much,” or “None at all.” The “A great deal” and “Quite a lot” options were collapsed into a binary “Confident” indicator, while “Not very much” and “None at all” options were collapsed into a “Not confident” indicator. [54]

The fieldwork for the Balkan Barometer 2016 Survey in North Macedonia was conducted in Macedonian and Albanian with a nationally representative sample of 1000 randomly selected adults residing in private homes, whose usual place of residence is in the country surveyed, and who speak the national languages well enough to respond to the questionnaire. Responses were weighted by demographic factors for both country-specific and regional demographic weights. [55] The research team did not provide an estimated error rate for the survey data.

The fieldwork for the Balkan Barometer 2019 Survey in North Macedonia was conducted in Macedonian and Albanian with a nationally representative sample of 1023 randomly selected adults residing in private homes, whose usual place of residence is in the country surveyed, and who speak the national languages well enough to respond to the questionnaire. Responses were weighted by demographic factors for both country-specific and regional demographic weights. [56] The research team did not provide an estimated error rate for the survey data.

The E&E region countries included in both waves of the Balkan Barometer survey were Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia. Respondents to the question “Have you ever done something that could affect any of the government decisions?” were allowed to choose multiple options from the following options: “Yes, I did, I took part in public debates,” “Yes, I did, I took part in protests,” “Yes, I did, I gave my comments on social networks or elsewhere on the Internet,” “I only discussed about it with friends, acquaintances, I have not publicly declared myself [sic],” “I do not even discuss about it [sic],” and “DK/refuse.” Most respondents selected only one option, however, due to double coding the values in this analysis were calculated by the total number of respondents who selected each option in any combination of responses, and therefore add up to a total percentage slightly greater than 100%. Balkan means were calculated using the regional respondent weights from all six Balkan Barometer countries.

Respondents to the Balkan Barometer 2016 question “What is the main reason you are not actively involved in government decision-making?” were allowed to choose a single response from the following options: “I as an individual cannot influence government decisions,” “I do not want to be publicly exposed,” “I do not care about it at all,” and “DK/refuse.” Balkan means were calculated using the regional respondent weights from all six Balkan Barometer countries. These response options differ from those available in 2019, so the two waves’ values cannot be directly compared for North Macedonia but should be assessed relative to the regional mean.

Respondents to the Balkan Barometer 2019 question “What is the main reason you are not actively involved in government decision-making?” were allowed to choose a single response from the following options: “The government knows best when it comes to citizen interests and I don't need to get involved,” “I vote and elect my representatives in the parliament so why would I do anything more,” “I as an individual cannot influence government decisions,” “I do not want to be publicly exposed,” “I do not trust this government and I don't want to have anything to do with them,” “I do not care about it at all,” and “DK/refuse.” Balkan means were calculated using the regional respondent weights from all six Balkan Barometer countries. These response options differ from those available in 2016, so the two waves’ values cannot be directly compared for North Macedonia but should be assessed relative to the regional mean.

The perceptions of corruption indicator uses responses to a series of Balkan Barometer 2019 questions which asks respondents “To what extent do you agree or not agree that [institution] in your economy is affected by corruption?” for several institutions (e.g., religious organizations, political parties, the military, NGOs, etc.). Respondents to the survey could select whether they “Totally agree,” “Tend to agree,” “Tend to disagree,” “Totally disagree,” or “DK/refuse.” The “Totally agree” and “Tend to agree” responses were collapsed into the binary indicator of “Agree” and the “Tend to disagree” and “Totally disagree” responses were collapsed into the binary indicator of “Disagree.” Regional means were calculated using the regional respondent weights from all six Balkan Barometer countries.

The Gallup World Poll was conducted annually in each of the E&E region countries from 2010-2021, except for the countries that did not complete fieldwork due to the coronavirus pandemic. Each country sample includes at least 1,000 adults and is stratified by population size and/or geography with clustering via one or more stages of sampling. The data are weighted to be nationally representative. The survey was conducted in Macedonian and Albanian each year from 2010 to 2021.