Moldova: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence

Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, Lincoln Zaleski

April 2023

Executive Summary

This report surfaces insights about the health of Moldova’s civic space and vulnerability to malign foreign influence in the lead up to Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Research included extensive original data collection to track Russian state-backed financing and in-kind assistance to civil society groups and regulators, media coverage targeting foreign publics, and indicators to assess domestic attitudes to civic participation and restrictions of civic space actors. Crucially, this report underscores that the Kremlin’s influence operations were not limited to Ukraine alone and illustrates its use of civilian tools in Moldova to co-opt support and deter resistance to its regional ambitions.

The analysis was part of a broader three-year initiative by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to produce quantifiable indicators to monitor civic space resilience in the face of Kremlin influence operations over time (from 2010 to 2021) and across 17 countries and 7 occupied or autonomous territories in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). Below we summarize the top-line findings from our indicators on the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Moldova, as well as channels of Russian malign influence operations:

- Restrictions of Civic Actors: Moldovan civic space actors were the targets of 212 restrictions between January 2015 and March 2021, including 14 instances in the occupied territory of Transnistria. Eighty-two percent of these restrictions involved harassment or violence, followed by newly proposed or implemented restrictive legislation (10 percent), and state-backed legal cases (8 percent). Thirty percent of these restrictions were recorded in 2018 alone, as campaigning began to heat up in advance of the February 2019 parliamentary elections. Formal CSOs were most frequently targeted. The Moldovan government was often the primary initiator, though in one case Chișinău worked at the behest of the Turkish government to detain and extradite seven school teachers accused of being part of the Gulen movement.

- Attitudes Towards Civic Participation: Although the majority (59-63 percent) of Moldovans expressed interest in politics between 2011-2018, this did not translate into high rates of political participation. As of 2018, only a minority had joined a petition (12 percent), boycott (6 percent) or demonstration (17 percent). This disconnect may be more about fear than apathy, for nearly 60 percent of Moldovans in 2018 said their fellow countrymen were afraid to openly express their political views. Nevertheless, Moldovans have found alternative avenues to offer practical support to their fellow citizens. In 2020, 70 percent of Moldovans reported helping a stranger and 24 percent gave money to charity. Similar to dynamics across the region, volunteerism was the lowest performing metric (16 percent).

- Russian-backed Civic Space Projects : The Kremlin supported 31 Moldovan civic organizations via 47 projects between January 2015 and August 2021. Not all of these Russian state organs were equally important: Rossotrudnichestvo accounted for 70 percent of the Kremlin’s overtures, followed by the Russian embassy in Chișinău and the Gorchakov Fund. Language and culture promotion, youth patriotic education and training, along with donations to local churches and the elderly. Moscow directed 64 percent of its projects to project influence in Gagauzia and occupied Transnistria. Many of these overtures are documented in the companion profile on the occupied territory of Transnistria.

- Russian State-run Media : Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News referenced Moldovan civic actors 427 times from January 2015 to March 2021. The 42 named domestic actors included civil society organizations, media outlets and political parties. Mentions of these domestic actors were primarily neutral (82 percent) in tone. The Kremlin oriented its negative coverage primarily anti-NATO and anti-EU narratives, compared to highly positive mentions of Russia-Moldova relations. Moldova was the fifth most referenced country in the E&E region in Russian state media coverage, lagging behind Ukraine, Belarus, Serbia, and tied with Georgia.

Table of Contents

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Moldova

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Moldova: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time

2.2 Attitudes Toward Civic Space in Moldova

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to Moldova’s Civic Space

3.2 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

5.3 Russian Financing and In-kind Support to Civic Space Actors or Regulators

5.4 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors and Democratic Rhetoric

Figures and Tables

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of Moldovan Civic Space Actors

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Moldova

Figure 2. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Moldova

Figure 3. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Moldova by Initiator

Figure 4. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Moldova by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Figure 5. Threatened versus Acted-on Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Moldova

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Moldova

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Moldova

Figure 7. Interest in Politics: Moldovan Citizens, 2011 and 2018

Figure 8. Political Action: Participation of Moldovan Citizens, 2018

Figure 9. Political Action: Moldovan Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2018

Figure 10. Civic Engagement Index: Moldova versus Regional Peers

Figure 11. Russian Projects Supporting Moldovan Civic Space Actors by Type

Figure 12. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Moldovan Civic Space

Figure 13. Locations of Russian Support to Moldovan Civic Space

Table 4. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in Moldova by Sentiment

Table 5. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Moldova by Sentiment

Figure 14. Russian State Media Mentions of Moldovan Civic Space Actors

Table 6. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, and Lincoln Zaleski. John Custer, Sariah Harmer, Parker Kim, and Sarina Patterson contributed editing, formatting, and supporting visuals. Kelsey Marshall and our research assistants provided invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report including: Jacob Barth, Kevin Bloodworth, Callie Booth, Catherine Brady, Temujin Bullock, Lucy Clement, Jeffrey Crittenden, Emma Freiling, Cassidy Grayson, Annabelle Guberman, Sariah Harmer, Hayley Hubbard, Hanna Kendrick, Kate Kliment, Deborah Kornblut, Aleksander Kuzmenchuk, Amelia Larson, Mallory Milestone, Alyssa Nekritz, Megan O’Connor, Tarra Olfat, Olivia Olson, Caroline Prout, Hannah Ray, Georgiana Reece, Patrick Schroeder, Samuel Specht, Andrew Tanner, Brianna Vetter, Kathryn Webb, Katrine Westgaard, Emma Williams, and Rachel Zaslavsk. The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

This research was made possible with funding from USAID's Europe & Eurasia (E&E) Bureau via a USAID/DDI/ITR Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) cooperative agreement (AID-A-12-00096). The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

A Note on Vocabulary

The authors recognize the challenge of writing about contexts with ongoing hot and/or frozen conflicts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consistently label groups of people and places for the sake of data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that terminology is political, but our use of terms should not be construed to mean support for one faction over another. For example, when we talk about an occupied territory, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the government in the capital. Or, when we analyze the de facto authorities’ use of legislation or the courts to restrict civic action, it is not to grant legitimacy to the laws or courts of separatists, but rather to glean meaningful insights about the ways in which institutions are co-opted or employed to constrain civic freedoms.

Citation

Custer, S., Mathew, D., Burgess, B., Dumont, E., Zaleski, L. (2023). Moldova: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence . April 2023. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William and Mary.

1. Introduction

How strong or weak is the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Moldova? To what extent do we see Russia attempting to shape civic space attitudes and constraints in Moldova to advance its broader regional ambitions? Over the last three years, AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—has collected and analyzed vast amounts of historical data on civic space and Russian influence across 17 countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). [1] In this country report, we present top-line findings specific to Moldova from a novel dataset which monitors four barometers of civic space in the E&E region from 2010 to 2021 (see Table 1). [2]

For the purpose of this project, we define civic space as: the formal laws, informal norms, and societal attitudes which enable individuals and organizations to assemble peacefully, express their views, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. [3] Here we provide only a brief introduction to the indicators monitored in this and other country reports. However, a more extensive methodology document is available via aiddata.org which includes greater detail about how we conceptualized civic space and operationalized the collection of indicators by country and year.

Civic space is a dynamic rather than static concept. The ability of individuals and organizations to assemble, speak, and act is vulnerable to changes in the formal laws, informal norms, and broader societal attitudes that can facilitate an opening or closing of the practical space in which they have to maneuver. To assess the enabling environment for Moldovan civic space, we examined two indicators: restrictions of civic space actors (section 2.1) and citizen attitudes towards civic space (section 2.2). Because the health of civic space is not strictly a function of domestic dynamics alone, we also examined two channels by which the Kremlin could exert external influence to dilute democratic norms or otherwise skew civic space throughout the E&E region. These channels are Russian state-backed financing and in-kind support to government regulators or pro-Kremlin civic space actors (section 3.1) and Russian state-run media mentions related to civic space actors or democracy (section 3.2).

Since restrictions can take various forms, we focus here on three common channels which can effectively deter or penalize civic participation: (i) harassment or violence initiated by state or non-state actors; (ii) the proposal or passage of restrictive legislation or executive branch policies; and (iii) state-backed legal cases brought against civic actors. Citizen attitudes towards political and apolitical forms of participation provide another important barometer of the practical room that people feel they have to engage in collective action related to common causes and interests or express views publicly. In this research, we monitored responses to citizen surveys related to: (i) interest in politics; (ii) past participation and future openness to political action (e.g., petitions, boycotts, strikes, protests); (iii) trust or confidence in public institutions; (iv) membership in voluntary organizations; and (v) past participation in less political forms of civic action (e.g., donating, volunteering, helping strangers).

In this project, we also tracked financing and in-kind support from Kremlin-affiliated agencies to: (i) build the capacity of those that regulate the activities of civic space actors (e.g., government entities at national or local levels, as well as in occupied or autonomous territories ); and (ii) co-opt the activities of civil society actors within E&E countries in ways that seek to promote or legitimize Russian policies abroad. Since E&E countries are exposed to a high concentration of Russian state-run media, we analyzed how the Kremlin may use its coverage to influence public attitudes about civic space actors (formal organizations and informal groups), as well as public discourse pertaining to democratic norms or rivals in the eyes of citizens.

Although Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine February 2022 undeniably altered the civic space landscape in Moldova and the broader E&E region for years to come, the historical information in this report is still useful in three respects. By taking the long view, this report sheds light on the Kremlin’s patient investment in hybrid tactics to foment unrest, co-opt narratives, demonize opponents, and cultivate sympathizers in target populations as a pretext or enabler for military action. Second, the comparative nature of these indicators lends itself to assessing similarities and differences in how the Kremlin operates across countries in the region. Third, by examining domestic and external factors in tandem, this report provides a holistic view of how to support resilient societies in the face of autocratizing forces at home and malign influence from abroad.

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

|

Civic Space Barometer |

Supporting Indicators |

|

Restrictions of civic space actors (January 2015–March 2021) |

|

|

Citizen attitudes toward civic space (2010–2021)

|

|

|

Russian projectized support relevant to civic space (January 2015–August 2021) |

|

|

Russian state media mentions of civic space actors (January 2015–March 2021) |

|

Notes: Table of indicators collected by AidData to assess the health of Moldova’s domestic civic space and vulnerability to Kremlin influence. Indicators are categorized by barometer (i.e., dimension of interest) and specify the time period covered by the data in the subsequent analysis.

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Moldova

A healthy civic space is one in which individuals and groups can assemble peacefully, express views and opinions, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. Laws, rules, and policies are critical to this space, in terms of rights on the books (de jure) and how these rights are safeguarded in practice (de facto). Informal norms and societal attitudes are also important, as countries with a deep cultural tradition that emphasizes civic participation can embolden civil society actors to operate even absent explicit legal protections. Finally, the ability of civil society actors to engage in activities without fear of retribution (e.g., loss of personal freedom, organizational position, and public status) or restriction (e.g ., constraints on their ability to organize, resource, and operate) is critical to the practical room they have to conduct their activities. If fear of retribution and the likelihood of restriction are high, this has a chilling effect on the motivation of citizens to form and participate in civic groups.

In this section, we assess the health of civic space in Moldova over time in two respects: the volume and nature of restrictions against civic space actors (section 2.1) and the degree to which Moldovans engage in a range of political and apolitical forms of civic life (section 2.2).

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Moldova: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time

Moldovan civic space actors experienced 212 known restrictions between January 2015 and March 2021 (see Table 2). These restrictions were weighted toward instances of harassment or violence (82 percent). There were fewer instances of state-backed legal cases (8 percent) and newly proposed or implemented restrictive legislation (10 percent); however, these instances can have a multiplier effect in creating a legal mandate for a government to pursue other forms of restriction. These imperfect estimates are based upon publicly available information either reported by the targets of restrictions, documented by a third-party actor, or covered in the news (see Section 5). [4]

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of Moldovan Civic Space Actors

|

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021-Q1 |

Total |

|

Harassment/Violence, excluding occupied Transnistria |

18 |

19 |

48 |

53 |

7 |

14 |

0 |

159 |

|

Harassment/Violence in occupied Transnistria [5] |

8 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

14 |

|

Restrictive Legislation |

5 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

22 |

|

State-backed Legal Cases |

6 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

17 |

|

Total |

37 |

29 |

55 |

63 |

9 |

19 |

0 |

212 |

Notes: Table of the number of restrictions initiated against civic space actors in Moldova, disaggregated by type and year. We have categorized all instances of restriction (including legislation and legal cases) in the occupied territory of Transnistria as “harassment/violence.” There were no identified restrictions during the first quarter of that year in Moldova or the occupied territory of Transnistria. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Moldova and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Instances of restrictions of Moldovan civic space actors were unevenly distributed across this time period and spiked in 2017 and 2018, no restrictions were recorded in the first quarter of 2021 (Figure 1). Thirty percent of cases were recorded in 2018 alone, particularly towards the latter part of the year, as campaigning began to heat up in advance of the February 2019 parliamentary elections. Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) were the most frequent targets of violence and harassment (Figure 2), followed by journalists and members of the media.

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Moldova

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment/Violence

Restrictive Legislation

State-backed Legal Cases

Key Events Relevant to Civic Space in Moldova

|

November 2014 |

The Moldovan National Bank uncovers ~$1 bn embezzlement from the banking system, causing a political crisis. |

|

January 2015 |

The occupied territory of Transnistria issues an anti-extremism order which promotes the perception that CSOs are foreign agents and sought to hinder their operations. |

|

September 2015 |

Mass protests grow as Moldovans call for early elections and the resignation of President Timofti, Red Bloc Party activists try to forcibly enter the prosecutor’s office. |

|

January 2016 |

Police use tear gas to disperse mass protests, after hundreds of activists break into the parliament building amidst dissension over who should be the new prime minister. |

|

June 2016 |

Former prime minister and pro-Euro politician Vlald Filat is convicted on charges connected to the 2014 bank scandal. Moldovans grow wary of pro-European parties. |

|

September 2016 |

The “parliament” of occupied Transnistria passes legislation giving itself greater authority over media outlets from appointing editorial staff to inhibiting registration and access to officials. |

|

November 2016 |

Igor Dodon, a pro-Russian politician is elected president and signals a negative opinion of pro-European forces. |

|

January 2017 |

The Ministry of Justice introduces articles into a draft law on non-commercial organizations seeking to prohibit political activities by those receiving foreign funding. |

|

May 2017 |

The government and pro-Dodon media intensify a verbal campaign to defame civic actors opposed to the country moving from proportional to mixed elections. |

|

December 2017 |

45 Moldovan NGOs condemn a second socio-political barometer survey commissioned by the Democratic Party of Moldova as stoking negative sentiment towards civil society. |

|

May 2018 |

A new law on non-governmental organizations entered into force in the Transnistria region which prohibits CSOs from engaging in political activities, broadly defined. |

|

August 2018 |

Mass protests break out in reaction to an earlier Supreme court ruling which invalidates the election of pro-European candidate Andrei Nastase in the Chișinău mayoral race. |

|

November 2018 |

A parliamentary commission accuses Open Dialogue (Otwarty Dialog) Foundation of money laundering, and seeks new legislation to eliminate NGO funding of political parties. |

|

February 2019 |

Parliamentary elections held in Moldova under a new parallel voting system, replacing the closed-list proportional system used at all previous parliamentary elections. |

|

June 2019 |

The Constitutional Court attempts to dismiss Igor Dodon and Maia Sandu (elected president and prime minister) and install Pavel Filip. The entire court ultimately resigns. |

|

November 2019 |

PM Maia Sandu's coalition fails when they fail to agree on how to appoint a prosecutor on the banking scandal. |

|

March 2020 |

The Audio-visual Council issues regulations for media about dissemination of information around the pandemic and then reverses course after public push back. |

|

June 2020 |

Moldova’s parliament passes legislation easing registration hurdles for NGOs, protecting their role in elections and funding from abroad, despite opposition from President Dodon. |

|

November 2020 |

Maia Sandu wins the presidential election, ousting Dodon. |

Figure 2. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Moldova

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

The Moldovan government was the most prolific initiator of restrictions of civic space actors, accounting for 90 recorded mentions. Compared with other countries in the region, the police were much less frequently the channel of restrictions enacted towards civic space actors. Instead, politicians and bureaucrats were more often the Initiators of hostility (Figure 3). Domestic non-governmental actors were identified as Initiators in 61 restrictions and there were some incidents involving unidentified assailants (8 mentions). By virtue of the way that the state-backed legal cases indicator was defined, the Initiators are either explicitly government agencies and government officials or clearly associated with these actors (e.g., the spouse or immediate family member of a sitting official). We used the category “De Facto Authorities – Occupied Territory” for the 14 instances of restriction identified in Transnistria, to recognize that local authorities in the occupied territory were the Initiators, as opposed to the Chișinău-based Moldovan government.

Figure 3. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Moldova by Initiator

Number of Instances Recorded

There was only one recorded instance of restrictions of civic space actors during this period involving a foreign government:

- In September 2018, Moldova’s Information and Security Service apprehended seven schoolteachers, all of whom were Turkish nationals who had applied for asylum in Moldova. They were accused of being part of the Gulen movement. The teachers were handed over to the Turkish authorities in a secret operation.

Figure 4 breaks down the targets of restrictions by political ideology or affiliation in the following categories: pro-democracy, pro-Western, and anti-Kremlin. [6] Pro-democracy organizations and activists were mentioned 115 times as targets of restriction during this period. [7] Pro-Western organizations and activists were mentioned 85 times as targets of restrictions. [8] There were 10 instances where we identified the target organizations or individuals to be explicitly anti-Kremlin in their public views. [9] It should be noted that this classification does not imply that these groups were targeted because of their political ideology or affiliation, merely that they met certain predefined characteristics. In fact, these tags were deliberately defined narrowly such that they focus on only a limited set of attributes about the organizations and individuals in question.

Figure 4. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Moldova by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment / Violence

Restrictive Legislation

State-backed Legal Cases

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

Instances of harassment (17 threatened, 138 acted upon) towards civic space actors were more common than episodes of outright physical harm (6 threatened, 12 acted upon) during the period. The majority of these restrictions (87 percent) were acted on, rather than threatened. However, since this data is collected on the basis of reported incidents, this likely understates threats which are less visible (see Figure 5). Of the 173 instances of harassment and violence, acted-on harassment accounted for the largest percentage (80 percent).

Figure 5. Threatened versus Acted-on Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Moldova

Number of Instances Recorded

Recorded instances of restrictive legislation (22) in Moldova are important to capture as they give government actors a mandate to constrain civic space with long-term cascading effects. This indicator is limited to a subset of parliamentary laws, chief executive decrees or other formal executive branch policies and rules that may have a deleterious effect on civic space actors, either subgroups or in general. Both proposed and passed restrictions qualify for inclusion, but we focus exclusively on new and negative developments in laws or rules affecting civic space actors. We exclude discussion of pre-existing laws and rules or those that constitute an improvement for civic space.

Taking a closer look at instances of restrictive legislation, the Moldovan government used a two-pronged approach to constrain civic space: (i) expanding the authorities’ ability to censor content and capture metadata from media outlets; and (ii) impeding the ability to operate and raise funds. A few illustrative examples include:

- Amendments to the existing Code and Law on Freedom of Expression were drafted to censor journalists and media outlets. The “Audiovisual Code” not only restricted the transmission of Russian language broadcasting but also limited access to foreign media content in general.

- A “Big Brother” law drafted in 2016 enabled the government to censor and surveil journalists, allowing the authorities to block content deemed to promote hatred, discrimination or violence, as well as requiring internet service providers to collect and retain users' metadata.

- A draft law in June 2017 introduced limits on the involvement of CSOs in political and human rights activities. It also restricted and imposed harsh penalties on organizations receiving foreign funding by creating arduous reporting requirements and excluding them from tax benefits.

Civic space actors were the targets of 17 recorded instances of state-backed legal cases between January 2015 and March 2021, with the highest volume in 2015. CSOs and NGOs were most frequently the defendants (Table 3), often charged in connection with their investigations into the financing of former Moldovan President Igor Dodon’s political campaigns. As shown in Figure 6, charges in these cases were most often directly (82 percent) tied to fundamental freedoms (e.g., freedom of speech, assembly). There were fewer indirect, but much more serious, charges (18 percent) such as forced labor or human trafficking, intended to discredit the reputations of civic space actors.

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Moldova

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

|

Defendant Category |

Number of Cases |

|

Media/Journalist |

1 |

|

Political Opposition |

5 |

|

Formal CSO/NGO |

6 |

|

Individual Activist/Advocate |

1 |

|

Other Community Group |

4 |

|

Other |

0 |

Notes: This table shows the number of state-backed legal cases against civic space actors in Moldova between January 2015–March 2021, disaggregated by the group targeted (i.e., political opposition, individual activist/advocate, media/journalist, other community group, formal CSO/NGO or other). This excludes entries related to the occupied territory of Transnistria, where all entries regardless of type were categorized as harassment/violence. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Moldova and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Moldova

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

2.2 Attitudes Toward Civic Space in Moldova

Moldovans have a relatively high level of reported interest in politics; however, this belies lower than expected levels of political participation in activities such as petitions, boycotts, or demonstrations. This disconnect may be more about fear than apathy, for a majority of Moldovans said their fellow countrymen were afraid to openly express their political views. Nevertheless, Moldovans have found alternative avenues to offer practical support to their fellow citizens, with an uptick in charitable donations and helping strangers coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic. In this section, we take a closer look at Moldovan citizens’ interest in politics and participation in political action. We also examine how Moldovans’ involvement in less political forms of civic engagement—donating to charities, volunteering for organizations, helping strangers—has evolved over time. Due to data availability limitations, we are unable to assess Moldovans’ membership in voluntary organizations or level of confidence in their institutions as in other country profiles.

2.2.1 Interest in Politics and Willingness to Act as Barometers of Moldovan Civic Space

Moldovans have sustained relatively high levels of interest in politics. Between 2011 and 2018, the proportion of Moldovans who said they had some level of interest in politics increased from 59 to 63 percent (+4 percentage points), according to two International Republican Institute (IRI) surveys (see Figure 7). By contrast, reported interest in politics across the E&E region fell from 42 to 36 percent (-6 percentage points), on average, during the same period. It should be noted that these regional estimates are based upon the 2011 World Values Survey Wave 6 and the Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey 2017-2021 which are similar, but distinct from the IRI instruments. [10]

Figure 7. Interest in Politics: Moldovan Citizens, 2011 and 2018

Percentage of Respondents

However, Moldovans’ higher interest in politics has not yet translated into greater participation in political action (Figure 8). As of 2018, only a small fraction of Moldovan respondents said they had joined a boycott (6 percent), petition (12 percent) or protest (17 percent). This low level of political participation is not unique to Moldova and tracks closely with the regional average, [11] but it is out of step with what we might expect to see given Moldovans’ relatively greater reported interest in politics.

Although Moldovans were more likely than their peers to have joined street protests (+7 percentage points), they were less likely to have signed a petition (-8 percentage points). Participation in boycotts was universally less attractive, as the regional average of 7 percent was similarly low to that in Moldova. It appears that the gap between political interest and action in Moldova is less likely due to apathy, but rather fear. According to a 2018 IRI survey, nearly 60 percent of Moldovan respondents said they believed that a large swath of the population was afraid to express their political views.

Looking forward, Moldovan survey respondents expressed greater willingness to join protests (29 percent), petitions (24 percent) or boycotts (16 percent) in the future than had participated in the past (Figure 9). The preference for protests and petitions over boycotts as a mode of political action aligns with general attitudes across the region. The greater relative popularity of protests among Moldovan respondents may be spurred by the increasing normalization of this channel of civic participation in recent years through the 2015 popular protests and 2016 parliamentary election protests.

Figure 8. Political Action: Participation of Moldovan Citizens, 2018 [12]

Percentage of Respondents

Figure 9. Political Action: Moldovan Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2018

Percentage of Respondents

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

The Gallup World Poll’s (GWP) Civic Engagement Index affords an additional perspective on Moldovan citizens’ attitudes towards less political forms of participation between 2010 and 2021. This index measures the proportion of citizens that reported giving money to charity, volunteering at organizations, and helping a stranger on a scale of 0 to 100. [13] Overall, Moldova charted the highest civic engagement in 2020-21, experienced a low point in 2013-14, but otherwise the country’s scores were relatively stable. Helping strangers appeared to be the main index component driving this variability. [14]

Towards the start of the period (2010-2012), Moldova’s civic engagement score was marginally ahead of the regional average—27 to 25 points, respectively (Figure 10). During this three-year period, 20 percent of Moldovan respondents reportedly gave money to charity, 19 percent volunteered at an organization, and 41 percent helped a stranger. These levels of apolitical participation by activity were roughly on par with the regional averages over the same period. Moldova’s civic engagement receded in 2013-14, as the country’s index score dropped to its lowest level (23 points) in 2014, trailing the regional average by 7 points that year. Notably, this dip precedes the 2015 anti-government protests, where citizens took to the streets to express outrage against corruption in mass protests. [15] There is some indication that Moldovan citizens’ willingness to volunteer in civic organizations is strongly and negatively correlated with the country’s economic performance. In other words, Moldovans’ enthusiasm for contributing their time to civic organizations appears to be relatively higher in periods of economic stress, than in times of prosperity. [16]

Following this period, Moldova’s civic engagement score stabilized and then reached its peak performance of the last decade in 2020 and 2021. Moldova’s 2020 index score improved by 9 points compared to the previous year, as 70 percent of Moldovans reported helping a stranger, 24 percent gave money to charity, and even rates of volunteering climbed to 16 percent (+4 percentage points). [17] Moldova’s civic engagement declined somewhat in 2021 but was still higher than at any point prior to 2020. This upward trend is consistent with improving civic engagement around the world as citizens rallied in response to COVID-19, even in the face of lockdowns and limitations on public gatherings. It remains to be seen whether this initial improvement will be sustained in future.

Figure 10. Civic Engagement Index: Moldova versus Regional Peers

3. External Channels of Influence: Kremlin Civic Space Projects and Russian State-Run Media in Moldova

Foreign governments can wield civilian tools of influence such as money, in-kind support, and state-run media in various ways that disrupt societies far beyond their borders. They may work with the local authorities who design and enforce the prevailing rules of the game that determine the degree to which citizens can organize themselves, give voice to their concerns, and take collective action. Alternatively, they may appeal to popular opinion by promoting narratives that cultivate sympathizers, vilify opponents, or otherwise foment societal unrest. In this section, we analyze data on Kremlin financing and in-kind support to civic space actors or regulators in Moldova (section 3.1), as well as Russian state media mentions related to civic space, including specific actors and broader rhetoric about democratic norms and rivals (section 3.2).

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to Moldova’s Civic Space

The Kremlin supported 31 known Moldovan civic space actors across 47 relevant projects between January 2015 and August 2021. Moscow prefers to directly engage and build relationships with individual civic actors, as opposed to investing in broader based institutional development which accounted for a mere 13 percent (6 projects) of its overtures (Figure 11). Notably, the Kremlin directed 64 percent of its support (30 projects) to project influence in Gagauzia and the occupied territory of Transnistria. Moscow doubled down on its engagement with Moldovan civic space in 2018 and 2019, nearly tripling the number of projects it supported. However, the Kremlin’s activities tapered off in 2020 and 2021, [18] likely due to a combination of COVID-19 related disruptions, as well as the election of the pro-European President Maia Sandu.

Figure 11. Russian Projects Supporting Moldovan Civic Space Actors by Type

Number of Projects Recorded, January 2015–August 2021

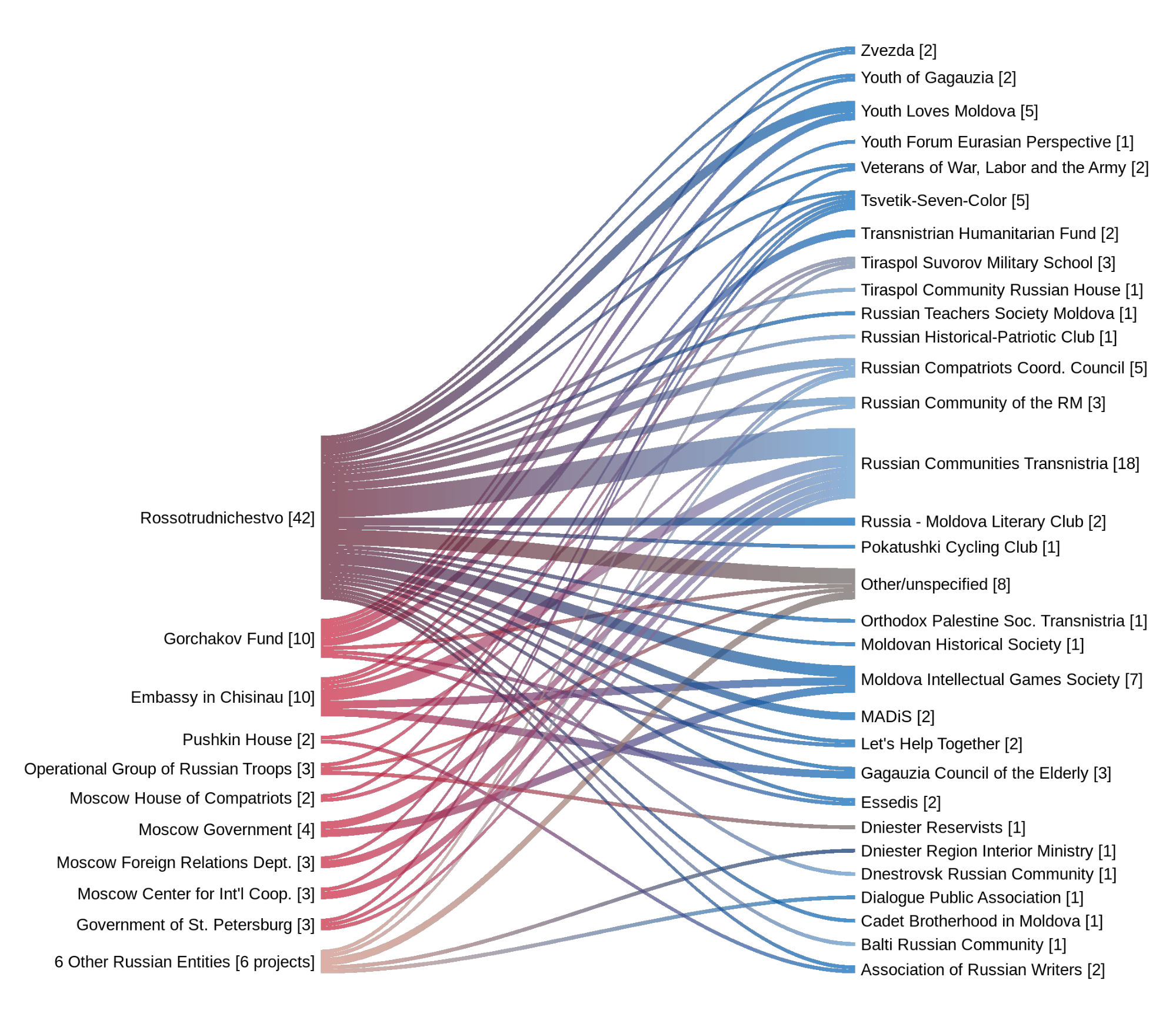

The Kremlin routed its engagement in Moldova through 16 different state channels (Figure 12), including numerous government ministries, federal centers, language and culture-focused funds, the embassy in Chișinău, municipal governments (Moscow, Moscow Oblast, and St. Petersburg), and Russian peacekeeping forces in the occupied territory of Transnistria. The stated missions of these Russian government entities emphasize themes such as education and culture promotion, economic development, and security related issues. Civil society development was more often a supporting theme, than the primary purpose of all but one of these entities.

However, not all of these Russian state organs were equally important. Rossotrudnichestvo [19] —an autonomous agency under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with a mandate to promote political and economic cooperation abroad—is associated with the majority (33 projects, 70 percent) of the Kremlin’s overtures to Moldovan civic actors. The Russian embassy in Chișinău and the Gorchakov Fund [20] , which aims to promote Russian culture and image abroad, were also prominent in partnering with Moldovan civic space actors.

Figure 12. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Moldovan Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

Notes: This figure shows which Kremlin-affiliated agencies (left-hand side) were involved in directing financial or in-kind support to which civil society actors or regulators (right-hand side) between January 2015 and August 2021. Lines are weighted to represent counts of projects such that thicker lines represent a larger volume of projects and thinner lines a smaller volume. The total weight of lines may exceed the total number of projects, due to many projects involving multiple donors and/or recipients. The following 6 Russian organizations were consolidated into Other Russian Entities because they were not ranked in the top 25: Embassy in Minsk [1], Ministry of Defense [1], Ministry of Emergency Situations [1], Moscow Region Government [1], Rosmolodezh [1], Russkiy Mir [1]. The number of projects is indicated in brackets. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

3.1.1 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Moldova’s Civic Space

Civil society organizations (CSOs) are not the only type of civic space actor in Moldova, but they were the most common beneficiaries in 56 percent of projects. Other non-governmental recipients of the Kremlin’s attention included Russian compatriot unions, along with schools, and churches. The Dniester Region Interior Ministry and a group of Dniester reservists also received projectized support from the Kremlin relevant to civic space.

The preponderance of the Moldovan recipient organizations worked in the education and culture sector (21 organizations), many with an emphasis on Russian language and culture promotion while others facilitate vocational training or patriotic education. The Kremlin also engaged with civic actors working on a broader set of issues related to social, religious, humanitarian, media, politics, and security concerns. Notably, a substantial number of the beneficiaries of Kremlin support were organizations that had an explicit emphasis on working with Moldovan youth (9 organizations).

Many Moldovan recipient organizations were comparatively more well established and deeply rooted in their communities than those with whom Russia engages with in other countries. For example, the International Association of Friendship and Cooperation "Moldova and Russia" (MADiS) [21] and the Russian Community of the Republic of Moldova were founded in 1994 and 1993, respectively, with guidance and support from the Russian State Committee for Federation and Nationalities Affairs. The Russian Community of Moldova is one of the few compatriot unions across the region [22] that is formally registered with the government. [23]

Geographically, Russia’s civic space overtures were disproportionately oriented to Gagauzia and the occupied territory of Transnistria, which attracted 15 and 45 percent of projects, respectively (Figure 13). The outsized attention paid by Moscow to these two occupied territories lends credence to the argument that the Kremlin is strategically deploying its support to stoke separatist tendencies, while consolidating its own influence. The remaining projects were primarily directed towards Chișinău or at least organizations based in the Moldovan capital, which received 34 percent of all projects (Figure 13).

Despite the upsurge in Russian projectized support to Moldovan civic space actors in 2017 and 2019 (see Figure 13), the Kremlin’s interest predated the election and subsequent victory of President Igor Dodon. Rossotrudnichestvo was developing plans to open an additional branch office in Tiraspol as far back as 2014, [24] a promise (as yet unfulfilled) which Transnistria’s de facto authorities highlighted somewhat controversially in a March 2016 speech by “Foreign Minister” Vitaliy Ignatyev a few weeks before the elections that would ultimately bring Dodon to power. [25]

Figure 13. Locations of Russian Support to Moldovan Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

3.1.2 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Moldova's Civic Space

The Kremlin has placed an outsized emphasis on two forms of support to individual Moldovan civic actors since 2015—event support and other in-kind contributions, referenced in 19 and 10 projects respectively. The nature of the Kremlin’s “support” is typically in the form of space, materials, or other logistical and technical contributions to Moldovan partners via its various organs. Russian institutions often co-sponsor activities with a Moldovan CSO, school or compatriot union, such as those focused on Russian literature or children’s education through puzzles and “intellectual games” in Chișinău or youth forums on Russian culture and history in the occupied territory of Transnistria. [26]

Moscow channeled support for military training and relationship-building with Transnistrian youth via the Russian Embassy, the Ministry of Defense, and the peacekeeping Operational Group of Russian Troops (i.e., Russian peacekeepers in the occupied territory of Transnistria). The Kremlin funded and furnished the new Suvorov military school in Tiraspol. At the opening, Transnistria’s de facto authorities emphasized the importance of the school in ensuring that future leaders of the defense ministry and law enforcement bodies will have, according to “President” Vadim Krasnoselskiy, “a good ideological background” and “a clear understanding of...the Dniester region.” [27]

Extending the Kremlin’s influence further, the Suvorov military school began accepting youth from Gagauzia to study as early as 2018. This youth training aligns with Moscow’s strategy in Gagauzia more generally, which centers on a longstanding partnership between Russian cultural organizations and the Bashkan (Governor) of Gagauzia to run a summer leadership school, “Gagauzia - Youth Autonomy,” for youth aged 16 to 30 years old [28] . The summer camp’s program includes political and leadership training, as well as frequent lectures by Russian representatives on topics such as Eurasian integration.

Moscow complements its youth-focused work in Gagauzia by distributing aid to local churches and the Council of the Elderly. Kremlin-affiliated organizations provide most of these donations in-kind (e.g., medical equipment, churchware). These goodwill gestures can be sizable: one church in Comrat (a Gagauzian municipality) received a donation of churchware worth 1.2 million rubles from the Moscow government in 2018, according to MP Fiodor Gagauz. The Kremlin works with churches and the elderly elsewhere in the region, most notably in Azerbaijan. However, the Kremlin’s provision of direct aid to the elderly and churches in Gagauzia is likely the result of “One Gagauzia” MP Gagauz’s active outreach on behalf of the region’s Orthodox churches and long-standing relations with the local Council of the Elderly.

3.2 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced Moldovan civic actors 427 times from January 2015 to March 2021. Roughly two-thirds of these mentions (300 instances) were of domestic actors, while the remaining third (127 instances) focused on foreign and intergovernmental actors operating in Moldova’s civic space. Russian state media covered a variety of civic actors, mentioning 74 organizations by name and 14 informal groups. In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of Moldovan citizens, we also analyzed 670 mentions of five keywords in conjunction with Moldova: North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO, the United States, the European Union, democracy, and the West. In this section, we examine Russian state media coverage of domestic and external civic space actors, how this has evolved over time, and the portrayal of democratic institutions and Western powers to Moldovan audiences.

3.2.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Moldovan Civic Space Actors

Roughly two-thirds (64 percent) of Russian media mentions of domestic actors in Moldova’s civic space referred to specific groups by name. The 42 named domestic actors included civil society organizations, media outlets and political parties (Table 4). Russian state media mentions of these Moldovan civic space actors were primarily neutral (82 percent) in tone.

Aside from these named organizations, TASS and Sputnik made 109 generalized mentions of 11 informal groups including protesters, opposition, Pro-European parties, and Moldovan media during the same period. The majority of this coverage was neutral (52 percent), though over a third was negative (34 percent), particularly related to protesters in the 2015–2016 Dignity and Truth demonstrations (13 instances). 100,000 Moldovans joined the protests organized by the Dignity and Truth (Dreptate și Adevăr or DA) Civic Platform, sparked by a billion-dollar corruption scandal that broke in November 2014. The protesters called for the dissolution of parliament, early elections, as well as the resignation of Moldovan President Nicolae Timofti and the government led by Prime Minister Valeriu Strelet.

Overall, the tone and high volume of Russian media mentions of Moldovan civic actors over a six-year period indicates the interest on the Kremlin’s part to use this channel to influence civic space events in the country. In general, coverage of domestic actors tended to be positive only for those that promoted the Kremlin’s interests in Moldova, such as those within the DA Civic Platform that advocated for a closer relationship with Russia through the Eurasian Economic Union, and the Party of Socialists of the Republic of Moldova (PSRM) which has an anti-NATO, anti-EU, and pro-Russian stance.

Table 4. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in Moldova by Sentiment

|

Domestic Civic Actor |

Extremely Negative |

Somewhat Negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat Positive |

Extremely Positive |

Grand Total |

|

Protesters |

2 |

19 |

31 |

9 |

0 |

61 |

|

Party of Socialists of the Republic of Moldova (PSRM) |

0 |

2 |

46 |

3 |

0 |

51 |

|

Our Party |

0 |

5 |

32 |

3 |

0 |

40 |

|

Dignity and Truth (DA) Civil Platform |

0 |

3 |

16 |

5 |

1 |

25 |

|

Opposition |

0 |

8 |

12 |

2 |

0 |

22 |

Notes: This table shows the breakdown of the domestic civic space actors most frequently mentioned by the Russian state media (TASS and Sputnik) between January 2015 to March 2021 and the tone of that coverage by individual mention. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

3.2.2 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in Moldovan Civic Space

Russian state media dedicated the remaining mentions (127 instances) to external actors operating in Moldova’s civic space. TASS and Sputnik mentioned 27 external actors by name including Voice of America, the International Republican Institute, and the United States Agency for Global Media. See Table 5. Russian state media mentioned 3 general foreign actors: Russian journalists (13 mentions), Western media (3 mentions), and Russian media (1 mention).

Russian state media mentions of external actors, both named and unnamed, were primarily neutral (57 percent) in tone. Contrary to the coverage of domestic civic actors, non-neutral mentions of external actors in Moldovan civic space tended to be positive (35 percent). All of the positive coverage was reserved for explicitly Russian or Russian-backed entities like Russian Peacekeepers in Moldova, Russian journalists and media in general, as well as named outlets including Channel One and Ruptly, and a human rights organization based in St. Petersburg, Civil Control.

Table 5. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Moldova by Sentiment

|

External Civic Group |

Extremely Negative |

Somewhat Negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat Positive |

Extremely Positive |

Grand Total |

|

Russian Peacekeepers in Moldova |

0 |

0 |

12 |

12 |

5 |

29 |

|

Russian Journalists |

0 |

0 |

4 |

9 |

0 |

13 |

|

LifeNews |

0 |

1 |

7 |

2 |

0 |

10 |

|

Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) |

0 |

0 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

|

All-Russian State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company (VGTRK) |

0 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

6 |

|

NTV |

0 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

6 |

Notes: This table shows the breakdown of the external civic space actors most frequently mentioned by the Russian state media (TASS and Sputnik) in relation to Moldova between January 2015 to March 2021 and the tone of that coverage by individual mention. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

3.2.3 Russian State Media’s Focus on Moldova’s Civic Space over Time

The preponderance of media mentions (68 percent) related to Moldova’s civic space centered around three events—(i) the ten-month popular protests from March 2015 to January 2016 (ii) the November 2016 presidential election and (iii) the February 2019 Parliamentary elections —all of which attracted largely neutral coverage by Russian state media.

Figure 14. Russian State Media Mentions of Moldovan Civic Space Actors

Number of Mentions Recorded

3.2.4 Russian State Media Coverage of Western Institutions and Democratic Norms

In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of Moldovan citizens, we analyzed the frequency and sentiment of coverage related to five keywords in conjunction with Moldova. [29] Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News referenced all five keywords from January 2015 to March 2021 (Table 6). Russian state media mentioned the European Union (285 instances), the United States (178 instances), the “West” (109 instances), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) (83 instances), and democracy (15 instances) with reference to Moldova during this period. The majority of mentions were neutral.

Table 6. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

|

Keyword |

Extremely negative |

Somewhat negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat positive |

Extremely positive |

Grand Total |

|

European Union |

9 |

81 |

177 |

18 |

0 |

285 |

|

United States |

12 |

22 |

133 |

11 |

0 |

178 |

|

West |

20 |

36 |

51 |

2 |

0 |

109 |

|

NATO |

18 |

29 |

31 |

5 |

0 |

83 |

|

Democracy |

2 |

1 |

3 |

7 |

2 |

15 |

Notes: This table shows the frequency and tone of mentions by Russian state media (TASS and Sputnik) related to five key words—NATO, the European Union, the United States, democracy, and the West—between January 2015 and March 2021 in articles related to Moldova. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Russian state media mentioned the European Union the most frequently (285 instances) in reference to Moldova. Sixty-two percent of these mentions were neutral, particularly in regard to the EU’s observer role during talks between Moldova and the occupied territory of Transnistria in 2016 and 2017, as well as the 2016 presidential elections. In the remaining coverage, the Kremlin was decidedly more negative (28 percent) towards the EU in stories related to public debates about Moldova’s joining the Eurasian Economic Union and whether the country should deprioritize its ties with the EU. For example, Russian state media portrayed Dodon as saying "if the Moldovan authorities decided to integrate politically into the European Union at some stage, it would blow up the country, and it might even lose its sovereignty." [30]

The next most frequently mentioned term was the United States (178 instances). The majority of mentions were neutral (75 percent) with many mentions referring to the United States’ role as an observer in the talks between Moldova and the occupied territory of Transnistria. Negative mentions (19 percent) were often centered around U.S. influence in Moldova, particularly in comparison to Russia.

The West received 109 mentions, roughly equally split between neutral and negative coverage. Several of the negative mentions occurred during the period before the 2019 parliamentary elections and included speculation that if the Socialist Party (PSRM), won then the West would organize a coup and contribute to a power struggle in Moldova. The West was also blamed for circulating anti-Russian rhetoric in the country.

NATO received 83 mentions, a slight majority of which were somewhat or extremely negative (57 percent). Moldovan President Dodon was staunchly anti-NATO, and Russian state media covered many of his remarks about the organization. Some of these instances include Dodon’s firing of a defense minister who recommended joining NATO, his cancellation of an agreement that would have established a liaison office in Chișinău, and the response to a NATO call for Russia to withdraw troops from the occupied territory of Transnistria.

Lastly, we recorded 15 mentions of democracy during this time period. The majority of mentions were positive. Many of these mentions occurred in reference to Moldovan presidential and parliamentary elections and spoke positively of democratic processes being followed.

4. Conclusion

The data and analysis in this report reinforces a sobering truth: Russia’s appetite for exerting malign foreign influence abroad is not limited to Ukraine, and its civilian influence tactics are already observable in Moldova and elsewhere across the E&E region. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see clearly how the Kremlin invested its media, money, and in-kind support to promote pro-Russian sentiment within Moldova and discredit voices wary of its regional ambitions in the years leading up to the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

The Kremlin was adept in deploying multiple tools of influence in mutually reinforcing ways to amplify the appeal of closer integration with Russia, raise doubts about the motives of the U.S., EU, and NATO, as well as legitimize its actions as necessary to protect the region’s security from the disruptive forces of democracy. Russian state media made a substantial effort to highlight Moldovan politicians’ comments that aligned with anti-Western rhetoric and pro-Russian sentiment, sowing skepticism about the appeal of the EU and NATO, while promoting a positive assessment of Russia as a natural security partner.

Similar to dynamics observed in other countries in the region, the Kremlin paid outsized attention to supporting the ambitions of Gagauzia and the occupied territory of Transnistria, who sought greater autonomy from Chișinău via youth summer camps, military training, and cultural programming. Russian overtures to Moldova were also highly concentrated around domestic political events that the Kremlin viewed as consequential to its foreign policy interests such as the popular protests in 2015-16, the November 2016 presidential election, and the February 2019 Parliamentary elections.

Taken together, it is more critical than ever to have better information at our fingertips to monitor the health of civic space across countries and over time, reinforce sources of societal resilience, and mitigate risks from autocratizing governments at home and malign influence from abroad. We hope that the country reports, regional synthesis, and supporting dataset of civic space indicators produced by this multi-year project is a foundation for future efforts to build upon and incrementally close this critical evidence gap.

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

In this section, we provide a brief overview of the data and methods used in the creation of this country report and the underlying data collection upon which these insights are based. More in-depth information on the data sources, coding, and classification processes for these indicators is available in our full technical methodology available on aiddata.org.

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

AidData collected and classified unstructured information on instances of harassment or violence, restrictive legislation, and state-backed legal cases from three primary sources: (i) CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Moldova; (ii) RefWorld database of documents and news articles pertaining to human rights and interactions with civilian law enforcement in Moldova operated by UNHCR; and (iii) Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. AidData supplemented this data with country-specific information sources from media associations and civil society organizations who report on such restrictions. Restrictions that took place prior to January 1, 2015 or after March 31, 2021 were excluded from data collection. It should be noted that there may be delays in reporting of civic space restrictions.

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

The data for citizen perceptions of civic space in Moldova are drawn from four sources. The Gallup World Poll and three additional public opinion surveys published by the International Republican Institute (IRI): the September 2011 National Voter Study, the March 2018 Public Opinion Survey, and the November 2018 Public Opinion Survey. Data on Moldovans’ interest in politics was drawn from the September 2011 National Voter Study and the March 2018 Public Opinion Survey. In both surveys, respondents were asked: “how much interest do you have in politics?” They could select from the following response options: “interested,” “medium interested,” “not interested” or “don’t know/NA.” Response options were further collapsed into “interested,” “not interested” or “don’t know/NA.” The March 2018 Public Opinion Survey also included the question: “are people in Moldova afraid or not to openly express their political views?” Respondents could select from the following responses: “Majority are afraid,” “Many are afraid,” “Some are afraid,” “Nobody is afraid,” and “Don’t know/NA.” The November 2018 Public Opinion Survey was the source of data on Moldovan’s past participation and future willingness to engage in various civic activities.

Conducted August 20 to September 2, 2011, the 2011 Moldova National Voter Study sample consisted of 1200 Moldovans aged 18 and older and eligible to vote. The survey had a response rate of 57.4 percent, an estimated margin of error of 3 percent. [31] The 2011 Moldova National Voter Study corresponds in terms of timing with the 2011 World Values Survey (WVS) which asks similar questions on political interest to facilitate broad comparisons with other countries in the Europe & Eurasia region.

IRI’s March 2018 Public Opinion Survey was conducted from February to March 2018 with a sample of 1513 Moldovan permanent residents aged 18 and older and eligible to vote. The survey had a 64 percent response rate and an estimated margin of error of 2.5 percent [32] . The March 2018 survey was selected to correspond with the 2018 European Values Survey (EVS) which asks similar questions on political interest to facilitate broad comparisons with other countries in the Europe & Eurasia region, as this question was excluded from the November 2018 IRI Survey.

IRI’s November 2018 Public Opinion Survey was conducted from September 11 to October 16, 2018 with a sample of 1503 Moldovan permanent residents aged 18 and older and eligible to vote. [33] The survey had a response rate of 68 percent and an estimated margin of error of 2.5 percent. The November 2018 survey was used for its inclusion of questions on participation in specific civic activities in Moldova that largely correspond to those included in the 2011 WVS and 2018 EVS studies: “participate in a protest,” “sign a petition,” and “participate in a boycott.” Respondents were asked two questions: “Have you ever engaged in any of the following activities?” and “Are you interested in engaging in any of the following activities within the next several years?” Participants were able to select “Yes,” “No,” or “Don’t know/No answer.” The 2018 IRI poll did ask about additional forms of civic participation—“attend a political meeting,” “contact an elected official,” post on social media,” “join a political party,” “join or support a formal or informal organization with a political agenda,” and “run for political office”—however, these were excluded from this analysis for the sake of consistency and comparability with data from other countries.

One option included in the WVS and EVS surveys not mentioned in the IRI list was the interest/experience of respondents in joining in a strike. This absence does not detract from the value of the data on the three priority actions.

For the regional citizen perceptions of civic space, we drew upon responses to two waves of a citizen survey: the World Values Survey (WVS) Wave 6 and the Joint European Values Study (EVS) / World Values Survey (WVS) 2017-2021. The WVS team partnered with the EVS team to design and conduct the EVS 2017 survey in Europe in such a way as to facilitate comparability between the two waves. As Moldova was not included in the survey design of either the WVS or the Joint EVS/WVS, comparisons with other countries in the region should be done cautiously as the instruments are similar, but not identical. However, we still incorporated some discussion of regional comparisons to Moldova in this profile as rougher benchmarks.

The E&E region countries included in WVS Wave 6, which were harmonized and designed for interoperable analysis, were Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine. Regional means for the question “How interested you have been in politics over the last 2 years?” were first collapsed from “Very interested,” “Somewhat interested,” “Not very interested,” and “Not at all interested” into the two categories: “Interested” and “Not interested.” Averages for the region were then calculated using the weighted averages from the seven countries.

Regional means for the WVS Wave 6 question “Now I’d like you to look at this card. I’m going to read out some different forms of political action that people can take, and I’d like you to tell me, for each one, whether you have actually done any of these things, whether you might do it or would never, under any circumstances, do it: Signing a petition; Joining in boycotts; Attending lawful demonstrations; Joining unofficial strikes” were calculated using the weighted averages from the seven E&E countries as well.

The E&E region countries included in the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 dataset, which were harmonized and designed for interoperable analysis, were Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, and Ukraine. Regional means for the question “How interested have you been in politics over the last 2 years?” were first collapsed from “Very interested,” “Somewhat interested,” “Not very interested,” and “Not at all interested” into the two categories: “Interested” and “Not interested.” Averages for the region were then calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen countries.

Regional means for the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 question “Now I’d like you to look at this card. I’m going to read out some different forms of political action that people can take, and I’d like you to tell me, for each one, whether you have actually done any of these things, whether you might do it or would never, under any circumstances, do it: Signing a petition; Joining in boycotts; Attending lawful demonstrations; Joining unofficial strikes” were calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen E&E countries as well.

The Gallup World Poll was conducted annually in each of the E&E region countries from 2010-2021, with the exception of the countries that did not complete fieldwork due to the coronavirus pandemic. Each country sample includes at least 1,000 adults and is stratified by population size and/or geography with clustering via one or more stages of sampling. The data are weighted to be nationally representative.

The Civic Engagement Index is an estimate of citizens’ willingness to support others in their community. It is calculated from positive answers to three questions: “Have you done any of the following in the past month? How about donated money to a charity? How about volunteered your time to an organization? How about helped a stranger or someone you didn’t know who needed help?” The engagement index is then calculated at the individual level, giving 33% to each of the answers that received a positive response. Moldova’s country values are then calculated from the weighted average of each of these individual Civic Engagement Index scores.

The regional mean is similarly calculated from the weighted average of each of those Civic Engagement Index scores, taking the average across all 17 E&E countries: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. The regional means for 2020 and 2021 are the exception. Gallup World Poll fieldwork in 2020 was not conducted for Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, and Turkmenistan. Gallup World Poll fieldwork in 2021 was not conducted for Azerbaijan, Belarus, Montenegro, and Turkmenistan.

5.3 Russian Financing and In-kind Support to Civic Space Actors or Regulators

AidData collected and classified unstructured information on instances of Russian financing and assistance to civic space identified in articles from the Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones between January 1, 2015 and August 30, 2021. Queries for Factiva Analytics pull together a collection of terms related to mechanisms of support (e.g., grants, joint training), recipient organizations, and concrete links to Russian government or government-backed organizations. In addition to global news, we reviewed a number of sources specific to each of the 17 target countries to broaden our search and, where possible, confirm reports from news sources. While many instances of Russian support to civic society or institutional development are reported with monetary values, a greater portion of instances only identified support provided in-kind, through modes of cooperation, or through technical assistance (e.g., training, capacity building activities). These were recorded as such without a monetary valuation.

5.4 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors and Democratic Rhetoric

AidData developed queries to isolate and classify articles from three Russian state-owned media outlets (TASS, Russia Today, and Sputnik) using the Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Articles published prior to January 1, 2015 or after March 31, 2021 were excluded from data collection. These queries identified articles relevant to civic space, from which AidData was able to record mentions of formal or informal civic space actors operating in Moldova. It should be noted that there may be delays in reporting of relevant news. Each identified mention of a civic space actor was assigned a sentiment according to a five-point scale: extremely negative, somewhat negative, neutral, somewhat positive, and extremely positive.

Russian state media mentions pertaining to democratic norms or democratic rivals are potentially consequential for civic space in E&E countries in a few different ways. AidData staff identified several keywords to operationalize this concept of democratic norms or democratic rivals in the E&E region including democracy, the European Union, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the United States, and the West:

-

Democracy: we include all mentions of the word “democracy” (except in the context of named organizations like “National Endowment for Democracy”). To measure anti-democracy sentiment, we also included mentions of different ideologies, including words related to democracy, fascism, authoritarianism, and dictatorships, which allows us to better explore Russian state media coverage of non-democratic sentiment.

-

European Union: we include both general terms “European Union” and “EU,” as well as specific EU bodies, such as “European Parliament,” “EU Courts,” “EU Human Rights Councils,” but not individuals.

-

NATO: we include both general terms “North Atlantic Treaty Organization” or “NATO,” as well as specific bodies associated with NATO, but not individuals.

-

United States: we include both general terms “United States,” “U.S.,” “American,” “America” (unless referring to the continents), as well as specific government bodies (such as Congress, US Department of State).” We do not include references to “White House” or specific individuals, with the exception of mentions of the president when combined with U.S./American in front.

- West: we include all non-geographic mentions of “West” or “Western,” but exclude geographic mentions of “west,” such as “the western portion of Armenia.”

Each identified mention of a keyword was assigned a sentiment according to a five-point scale: extremely negative, somewhat negative, neutral, somewhat positive, and extremely positive.

[1] The 17 countries include Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

[2] The specific time period varies by year, country, and indicator, based upon data availability.

[3] This definition includes formal civil society organizations and a broader set of informal civic actors, such as political opposition, media, other community groups (e.g., religious groups, trade unions, rights-based groups), and individual activists or advocates. Given the difficulty to register and operate as official civil society organizations in many countries, this definition allows us to capture and report on a greater diversity of activity that better reflects the environment for civic space. We include all these actors in our indicators, disaggregating results when possible.

[4] Much like with other cases of abuse, assault, and violence against individuals, where victims may fear retribution or embarrassment, we anticipate that this number may understate the true extent of restrictions.

[5] AidData’s profile of Transnistria offers a more in-depth analysis of the occupied territory.

[6] These tags are deliberately defined narrowly such that they likely understate, rather than overstate, selective targeting of individuals or organizations by virtue of their ideology. Exclusion of an individual or organization from these classifications should not be taken to mean that they hold views that are counter to these positions (i.e., anti-democracy, anti-Western, pro-Kremlin).

[7] A target organization or individual was only tagged as pro-democratic if they were a member of the political opposition (i.e., thus actively promoting electoral competition) and/or explicitly involved in advancing electoral democracy, narrowly defined.

[8] A tag of pro-Western was applied only when there was a clear and publicly identifiable linkage with the West by virtue of funding or political views that supported EU integration, for example.

[9] The anti-Kremlin tag is only applied in instances where there is a clear connection to opposing actions of the Russian government writ large or involving an organization that explicitly positioned itself as anti-Kremlin in ideology.

[10] Unfortunately, the most recent EVS or WVS study was conducted in Moldova in 2006. While the exact formulation of questions differs from the IRI surveys, preventing direct comparisons, both have similar questions on interest in politics and similar questions on involvement in petitions, boycotts, and demonstrations.

[11] As reported via similar questions on the Joint EVS/WVS 2017–2021.

[12] Question text: Are you interested in engaging in any of the following activities within the next several years? Unlike the World Values Survey 2011 and European Values Survey 2018, the IRI 2018 poll does not include information on participation in strikes among the response options.

[13] The GWP Civic Engagement Index is calculated at an individual level, with 33% given for each of three civic-related activities (Have you” Donated money to charity? Volunteered your time to an organization in the past month?, Helped a stranger or someone you didn't know in the past month?) that received a “yes” answer. The country score is then determined by calculating the weighted average of these individual Civic Engagement Index scores.

[14] Helping strangers correlated with the overall index at 0.938***, p = 0.000, while donating to charity correlated at 0.524, p = 0.374, and volunteering correlated at 0.092, p = 1.000.

[15] https://www.politico.eu/article/moldovas-maidan/

[16] That said, volunteerism was not a major driver of Moldova’s overall civic engagement score, so it is likely that factors other than economic performance over the past decade had a more decisive influence on citizens’ participation across all types of apolitical activities overall.

[17] Indeed, this is consistent with the earlier finding that volunteering rates appeared to move opposite to the economy as a whole, as Moldova’s GDP declined 7 percent from 2019 to 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=MD

[18] Following AidData’s original collection of data for the period January 2015 through September 2020, we conducted an update for the period October 2020 through August 2021 and identified no new activities.