Georgia: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence

Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, Lincoln Zaleski

April 2023

[Skip to Table of Contents] [Skip to Chapter 1]Executive Summary

This report surfaces insights about the health of Georgia’s civic space and vulnerability to malign foreign influence in the lead up to Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Research included extensive original data collection to track Russian state-backed financing and in-kind assistance to civil society groups and regulators, media coverage targeting foreign publics, and indicators to assess domestic attitudes to civic participation and restrictions of civic space actors. Crucially, this report underscores that the Kremlin’s influence operations were not limited to Ukraine alone and illustrates its use of civilian tools in Georgia to co-opt support and deter resistance to its regional ambitions.

The analysis was part of a broader three-year initiative by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to produce quantifiable indicators to monitor civic space resilience in the face of Kremlin influence operations over time (from 2010 to 2021) and across 17 countries and 7 occupied or autonomous territories in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). Below we summarize the top-line findings from our indicators on the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Georgia, as well as channels of Russian malign influence operations:

- Restrictions of Civic Actors: Georgian civic space actors were the targets of 305 restrictions between January 2015 and March 2021, including harassment or violence (84 percent), state-backed legal cases (8 percent) and restrictive legislation (8 percent). Twenty-four percent of cases occurred in 2019, coinciding with protests against a Russian delegation visit in June and the Georgian Dream party’s proposed transition to a fully proportional voting system in 2020. Political opposition members were most frequently targeted, and the Georgian government was the primary initiator. Foreign governments were involved in five instances of restriction, including Turkey (2) and Azerbaijan (3).

- Attitudes Towards Civic Participation: Georgian citizens were less interested in politics but surpassed their regional peers in other Europe and Eurasia countries in political participation (e.g., demonstrations, strikes, boycotts, petitions) in 2014 and 2018. Generally low membership rates in voluntary organizations and low levels of confidence in institutions likely continues to have a chilling effect on Georgians’ civic participation, with religious organizations as a notable exception. Georgians’ willingness to engage in less political forms of civic life generally improved over the last decade, reaching a high in 2020, before backtracking. In 2021, 69 percent of Georgians reported helping a stranger, but only a minority volunteered their time (22 percent) or made charitable donations (3 percent).

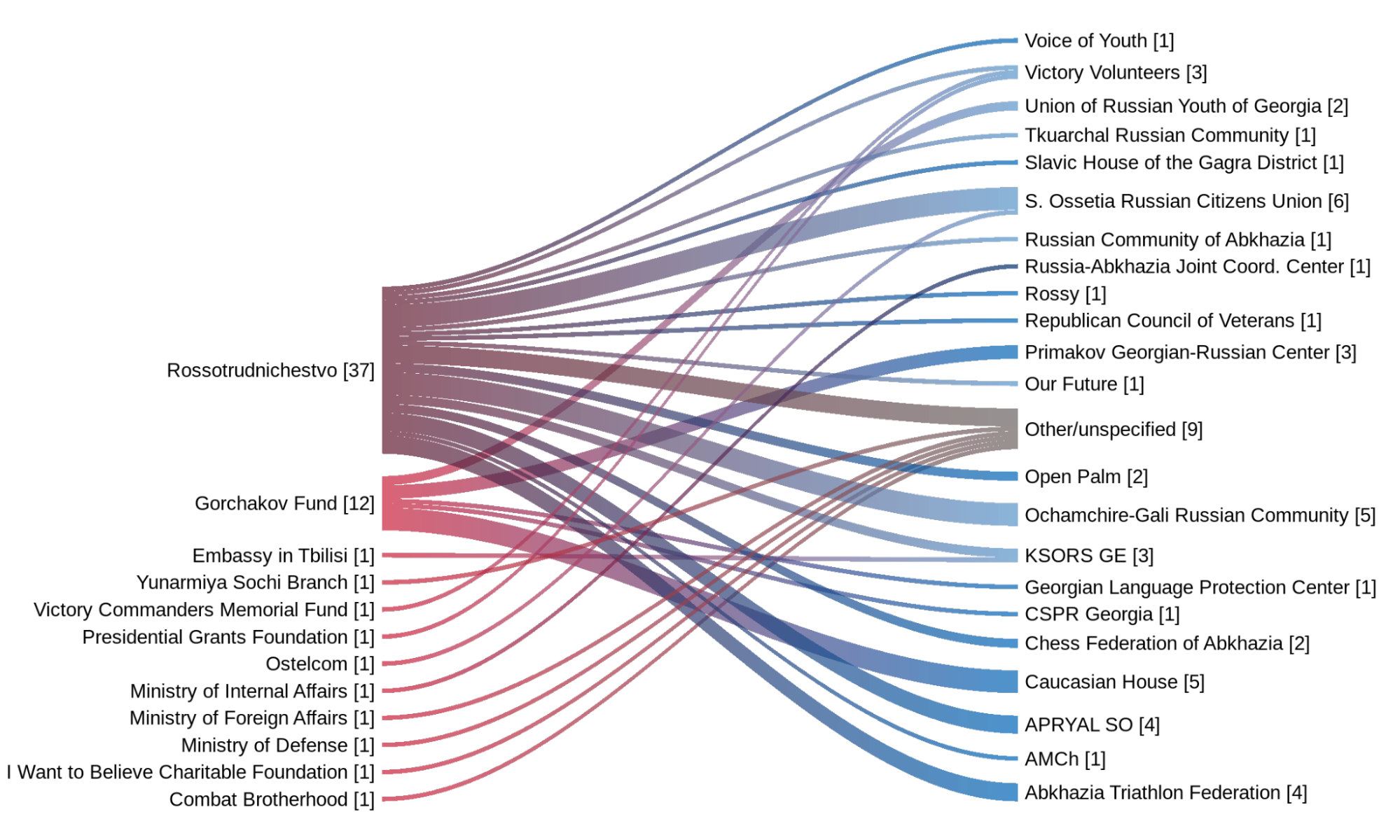

- Russian-backed Civic Space Projects: The Kremlin supported 22 Georgian civic organizations via 46 civic space-relevant projects between January 2015 and August 2021. Kremlin-backed civic space projects centered on promoting Russian linguistic and cultural ties in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia, in line with Moscow’s consistent emphasis on cultural promotion and occupied territories. The Kremlin routed its engagement in Georgia through 12 different channels but two organizations, Rossotrudnichestvo and the Gorchakov Fund, were involved in 95 percent of the projects.

- Russian State-run Media: Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News referenced Georgian civic actors 622 times from January 2015 to March 2021. FForty-three percent of civic space actor mentions occurred in just two months—June to July 2019—in relation to a series of anti-Russian protests. More broadly, the Kremlin used its media coverage to discredit pro-European or Western-affiliated organizations, promote pro-Kremlin voices, and deter Georgia’s aspirations to join NATO and the European Union.

Table of Contents

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Georgia

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Georgia: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

2.2 Attitudes Toward Civic Space in Georgia

2.2.1 Interest in Politics and Willingness to Act as Barometers of Georgian Civic Space

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to Georgia’s Civic Space

3.1.1 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Georgia’s Civic Space

3.1.2 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Georgia's Civic Space

3.2 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

3.2.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Georgian Civic Space Actors

3.2.2 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in Georgian Civic Space

3.2.3 Russian State Media’s Focus on Georgia’s Civic Space over Time

3.2.4 Russian State Media Coverage of Western Institutions and Democratic Norms

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

5.3 Russian Projectized Support to Civic Space Actors or Regulators

5.4 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

Figures and Tables

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of Georgian Civic Space Actors

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Georgia

Figure 2. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Georgia

Figure 3. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Georgia by Initiator

Figure 4. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Georgia by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Figure 5. Threatened versus Acted-on Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Georgia

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Georgia

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Georgia

Figure 7. Interest in Politics: Georgian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2014 and 2018

Figure 8. Political Action: Georgian Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2014 versus 2018

Figure 9. Political Action: Participation by Georgian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2014 and 2018

Figure 10. Voluntary Organization Membership: Georgian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2014 and 2018

Table 4. Georgian Citizens’ Membership in Voluntary Organizations by Type, 2014 and 2018

Table 5. Georgian Confidence in Key Institutions, 2014 and 2018

Figure 11. Civic Engagement Index: Georgia versus Regional Peers

Figure 12. Russian Projects Supporting Georgian Civic Space Actors by Type

Figure 13. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Georgian Civic Space

Figure 14. Locations of Russian Support to Georgian Civic Space

Table 6. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in Georgia by Sentiment

Table 7. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Georgia by Sentiment

Figure 15. Russian State Media Mentions of Georgian Civic Space Actors

Figure 16. Keyword Mentions by Russian State Media in Relation to Georgia

Table 8. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, and Lincoln Zaleski. John Custer, Sariah Harmer, Parker Kim, and Sarina Patterson contributed editing, formatting, and supporting visuals. Kelsey Marshall and our research assistants provided invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report including: Jacob Barth, Kevin Bloodworth, Callie Booth, Catherine Brady, Temujin Bullock, Lucy Clement, Jeffrey Crittenden, Emma Freiling, Cassidy Grayson, Annabelle Guberman, Sariah Harmer, Hayley Hubbard, Hanna Kendrick, Kate Kliment, Deborah Kornblut, Aleksander Kuzmenchuk, Amelia Larson, Mallory Milestone, Alyssa Nekritz, Megan O’Connor, Tarra Olfat, Olivia Olson, Caroline Prout, Hannah Ray, Georgiana Reece, Patrick Schroeder, Samuel Specht, Andrew Tanner, Brianna Vetter, Kathryn Webb, Katrine Westgaard, Emma Williams, and Rachel Zaslavsk. The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

This research was made possible with funding from USAID's Europe & Eurasia (E&E) Bureau via a USAID/DDI/ITR Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) cooperative agreement (AID-A-12-00096). The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

A Note on Vocabulary

The authors recognize the challenge of writing about contexts with ongoing hot and/or frozen conflicts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consistently label groups of people and places for the sake of data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that terminology is political, but our use of terms should not be construed to mean support for one faction over another. For example, when we talk about an occupied territory, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the government in the capital. Or, when we analyze the de facto authorities’ use of legislation or the courts to restrict civic action, it is not to grant legitimacy to the laws or courts of separatists, but rather to glean meaningful insights about the ways in which institutions are co-opted or employed to constrain civic freedoms.

Citation

Custer, S., Mathew, D., Burgess, B., Dumont, E., Zaleski, L. (2023). Georgia: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence. April 2023. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William and Mary.

1. Introduction

How strong or weak is the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Georgia? To what extent do we see Russia attempting to shape civic space attitudes and constraints in Georgia to advance its broader regional ambitions? Over the last three years, AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—has collected and analyzed vast amounts of historical data on civic space and Russian influence across 17 countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). [1] In this country report, we present top-line findings specific to Georgia from a novel dataset which monitors four barometers of civic space in the E&E region from 2010 to 2021 (Table 1). [2]

For the purpose of this project, we define civic space as: the formal laws, informal norms, and societal attitudes which enable individuals and organizations to assemble peacefully, express their views, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. [3] Here we provide only a brief introduction to the indicators monitored in this and other country reports. However, a more extensive methodology document is available via aiddata.org which includes greater detail about how we conceptualized civic space and operationalized the collection of indicators by country and year.

Civic space is a dynamic rather than static concept. The ability of individuals and organizations to assemble, speak, and act is vulnerable to changes in the formal laws, informal norms, and broader societal attitudes that can facilitate an opening or closing of the practical space in which they have to maneuver. To assess the enabling environment for Georgian civic space, we examined two indicators: restrictions of civic space actors (section 2.1) and citizen attitudes towards civic space (section 2.2). Because the health of civic space is not strictly a function of domestic dynamics alone, we also examined two channels by which the Kremlin could exert external influence to dilute democratic norms or otherwise skew civic space throughout the E&E region. These channels are Russian state-backed financing and in-kind support to government regulators or pro-Kremlin civic space actors (section 3.1) and Russian state-run media mentions related to civic space actors or democracy (section 3.2).

Since restrictions can take various forms, we focus here on three common channels which can effectively deter or penalize civic participation: (i) harassment or violence initiated by state or non-state actors; (ii) the proposal or passage of restrictive legislation or executive branch policies; and (iii) state-backed legal cases brought against civic actors. Citizen attitudes towards political and apolitical forms of participation provide another important barometer of the practical room that people feel they have to engage in collective action related to common causes and interests or express views publicly. In this research, we monitored responses to citizen surveys related to: (i) interest in politics; (ii) past participation and future openness to political action (e.g., petitions, boycotts, strikes, protests); (iii) trust or confidence in public institutions; (iv) membership in voluntary organizations; and (v) past participation in less political forms of civic action (e.g., donating, volunteering, helping strangers).

In this project, we also tracked financing and in-kind support from Kremlin-affiliated agencies to: (i) build the capacity of those that regulate the activities of civic space actors (e.g., government entities at national or local levels, as well as in occupied or autonomous territories ); and (ii) co-opt the activities of civil society actors within E&E countries in ways that seek to promote or legitimize Russian policies abroad. Since E&E countries are exposed to a high concentration of Russian state-run media, we analyzed how the Kremlin may use its coverage to influence public attitudes about civic space actors (formal organizations and informal groups), as well as public discourse pertaining to democratic norms or rivals in the eyes of citizens.

Although Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine February 2022 undeniably altered the civic space landscape in Georgia and the broader E&E region for years to come, the historical information in this report is still useful in three respects. By taking the long view, this report sheds light on the Kremlin’s patient investment in hybrid tactics to foment unrest, co-opt narratives, demonize opponents, and cultivate sympathizers in target populations as a pretext or enabler for military action. Second, the comparative nature of these indicators lends itself to assessing similarities and differences in how the Kremlin operates across countries in the region. Third, by examining domestic and external factors in tandem, this report provides a holistic view of how to support resilient societies in the face of autocratizing forces at home and malign influence from abroad.

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

|

Civic Space Barometer |

Supporting Indicators |

|

Restrictions of civic space actors (January 2015–March 2021) |

|

|

Citizen attitudes toward civic space (2010–2021)

|

|

|

Russian projectized support relevant to civic space (January 2015–August 2021) |

|

|

Russian state media mentions of civic space actors (January 2015–March 2021) |

|

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Georgia

A healthy civic space is one in which individuals and groups can assemble peacefully, express views and opinions, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. Laws, rules, and policies are critical to this space, in terms of rights on the books (de jure) and how these rights are safeguarded in practice (de facto). Informal norms and societal attitudes are also important, as countries with a deep cultural tradition that emphasizes civic participation can embolden civil society actors to operate even absent explicit legal protections. Finally, the ability of civil society actors to engage in activities without fear of retribution (e.g., loss of personal freedom, organizational position, and public status) or restriction (e.g ., constraints on their ability to organize, resource, and operate) is critical to the practical room they have to conduct their activities. If fear of retribution and the likelihood of restriction are high, this has a chilling effect on the motivation of citizens to form and participate in civic groups.

In this section, we assess the health of civic space in Georgia over time in two respects: the volume and nature of restrictions against civic space actors (section 2.1) and the degree to which Georgians engage in a range of political and apolitical forms of civic life (section 2.2).

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Georgia: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time

Georgian civic space actors experienced 305 known restrictions between January 2015 and March 2021 (see Table 2). These restrictions were weighted toward instances of harassment or violence (84 percent). There were fewer instances of state-backed legal cases (8 percent) and newly proposed or implemented restrictive legislation (8 percent); however, these instances can have a multiplier effect in creating a legal mandate for a government to pursue other forms of restriction. These imperfect estimates are based upon publicly available information either reported by the targets of restrictions, documented by a third-party actor, or covered in the news (see Section 5). [4]

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of Georgian Civic Space Actors

|

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021-Q1 |

Total |

|

Harassment/Violence |

52 |

36 |

21 |

36 |

61 |

24 |

10 |

241 |

|

Harassment/Violence in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia [5] |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

|

Harassment/Violence in Georgia’s Russia-occupied South Ossetia [6] |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

14 |

|

Restrictive Legislation |

5 |

5 |

7 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

26 |

|

State-backed Legal Cases |

3 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

11 |

3 |

1 |

24 |

|

Total |

64 |

47 |

34 |

42 |

75 |

32 |

11 |

305 [7] |

Instances of restrictions of Georgian civic space actors were unevenly distributed across this time period and spiked in 2019 (Figure 1). Twenty-four percent of cases were recorded in 2019 alone, coinciding with mass protests against the visit of a Russian delegation in June. Thousands of Georgians took to the streets as Duma member Sergei Gavrilov addressed an inter-parliamentary session of lawmakers in Russian, seated in the Speaker’s chair at the Georgian Parliament. Anti-government protests broke out again in November 2019, as the Georgian Dream party proposed an election bill to accelerate the transition to a fully proportional voting system in 2020, instead of waiting until 2024, as set out by the 2017 constitution. Political opposition members were the most frequent targets of violence and harassment, in 40 percent of all recorded instances (Figure 2), followed by journalists and other members of the media.

The Georgian government was the most prolific initiator of restrictions of civic space actors, accounting for 150 recorded mentions. The police were frequently the channel of restrictions enacted towards civic space actors. Politicians and bureaucrats were sometimes the initiators of hostility (Figure 3). Domestic non-governmental actors were identified as initiators in 72 restrictions and there were some incidents involving unidentified assailants (28 mentions). By virtue of the way that the state-backed legal cases indicator was defined, the initiators are either explicitly government agencies and government officials or clearly associated with these actors (e.g., the spouse or immediate family member of a sitting official). We used the category “De Facto Authorities – Occupied Territory” for the 16 instances of restriction identified in the two Russia-occupied territories to recognize that local authorities in the occupied territory were the initiators, as opposed to the Tbilisi-based Georgian government.

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Georgia

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment/Violence

Restrictive Legislation

State-backed Legal Cases

Key Events Relevant to Civic Space in Georgia

|

March 2015 |

Russia signs an "alliance and integration" treaty with Georgia’s Russia-occupied South Ossetia. The treaty is denounced by the Georgian government. |

|

May 2015 |

Exiled Former President Saakashvili is appointed Governor of Odessa in Ukraine. He vows to return and unseat the Georgian Dream. |

|

December 2015 |

Prime Minister Garibashvili resigns after months of falling poll ratings for the coalition. He is replaced by foreign minister Giorgi Kvirikashvili. |

|

October 2016 |

The governing Georgian Dream coalition wins parliamentary elections with an enhanced majority. |

|

April 2017 |

Georgia’s Russia-occupied South Ossetia holds presidential elections and a referendum on changing its name to the State of Alania as part of a plan to join the Russian Federation. |

|

September 2017 |

Georgia adopts a new constitution. Opposition parties walk out of parliament in protest, concerned over threats to democracy. |

|

May 2018 |

Tbilisi sees protests following a 'not guilty' verdict for a suspect in the murder of two teenagers. Protesters demand the government's resignation. |

|

December 2018 |

Salome Zourabichvili becomes Georgia's first female President, ostensibly the last popularly elected one, before constitutional changes come into effect. |

|

June 2019 |

Thousands protest as Duma member Sergei Gavrilov makes an address, from the Georgian parliamentary speaker's seat, in Russian. |

|

September 2019 |

Mamuka Bakhtadze resigned due to the protests. Giorgi Gakharia is nominated to the post of Prime Minister. |

|

February 2020 |

Russianization began in Akhalgori District of Georgia’s Russia-occupied territory of South Ossetia. Speaking in Georgian is banned at schools. |

|

January 2021 |

Europe's top human rights court finds Russia responsible for violations in Georgia's occupied territories after the 2008 Russia-Georgia war. |

Figure 2. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Georgia

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

Figure 3. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Georgia by Initiator

Number of Instances Recorded

There were five recorded instances of restrictions of civic space actors during this period involving foreign governments:

- Two incidents involved the government of Turkey. In February 2017, a Gulen school in Tbilisi lost its license, and reporting suggests that this was done in cooperation with Ankara. In May 2017, Mustafa Emre Cabuk, a secondary school teacher living in Georgia was detained at the request of the Turkish authorities. He is accused of having ties with followers of Fetullah Gulen.

- The government of Azerbaijan was involved in three incidents. Afghan Mukhtarli, an Azerbaijani journalist known for criticizing the Baku authorities, was kidnapped in Tbilisi, forcibly returned to Azerbaijan, and arrested upon his arrival in May 2017. In September 2018, Azerbaijani activist Azer Kazimzade, a vocal critic of the Azerbaijani authorities, was arrested in Tbilisi. It is unlikely that Kazimzade’s detention did not have tacit approval from Baku. In June 2019, Azerbaijani activist Avtandil Mammadov was detained in Georgia on an extradition request from Azerbaijan.

Figure 4 breaks down the targets of restrictions by political ideology or affiliation in the following categories: pro-democracy, pro-Western, and anti-Kremlin. [8] Pro-democracy organizations and activists were mentioned 191 times as targets of restriction during this period. [9] Pro-Western organizations and activists were mentioned 109 times as targets of restrictions. [10] There were 58 instances where we identified the target organizations or individuals to be explicitly anti-Kremlin in their public views. [11] It should be noted that this classification does not imply that these groups were targeted because of their political ideology or affiliation, merely that they met certain predefined characteristics. In fact, these tags were deliberately defined narrowly such that they focus on only a limited set of attributes about the organizations and individuals in question.

Figure 4. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Georgia by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment / Violence

Restrictive Legislation

State-backed Legal Cases

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

Instances of harassment (10 threatened, 165 acted upon) towards civic space actors were more common than episodes of outright physical harm (9 threatened, 71 acted upon) during the period. The vast majority of these restrictions (92 percent) were acted on, rather than merely threatened. However, since this data is collected on the basis of reported incidents, this likely understates threats which are less visible (see Figure 5). Of the 255 instances of harassment and violence, acted-on harassment accounted for the largest percentage (65 percent).

Figure 5. Threatened versus Acted-on Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Georgia

Number of Instances Recorded

Recorded instances of restrictive legislation (26) in Georgia are important to capture as they give government actors a mandate to constrain civic space with long-term cascading effects. This indicator is limited to a subset of parliamentary laws, chief executive decrees or other formal executive branch policies and rules that may have a deleterious effect on civic space actors, either subgroups or in general. Both proposed and passed restrictions qualify for inclusion, but we focus exclusively on new and negative developments in laws or rules affecting civic space actors. We exclude discussion of pre-existing laws and rules or those that constitute an improvement for civic space.

A new constitution was drafted and adopted in September 2017, which was arguably the most significant legislative development between 2015 and 2020. When the constitution was adopted with 117 votes, opposition parties walked out of parliament in protest against upcoming changes to the electoral system. The political opposition and several Georgian CSOs viewed these changes as a threat to democracy. Other concerns about the new constitution included a lack of accountability within law enforcement and security agencies, and a more restrictive media environment.

A close look at other instances of restrictive legislation in Georgia highlight two threats to a vital civic space: (i) censorship and (ii) surveillance. These strictures create an atmosphere of distrust and unease, diminishing the health of the civic space. A few illustrative examples include:

- Censorship: In early 2015, amendments to the Criminal Code outlawed “public calls to violent action.” Human rights defenders expressed concerns that the law could be selectively applied to target legitimate expression. In December 2015, a parliamentarian from the ruling Georgian Dream party proposed and then withdrew [12] a law that would have criminalized “insulting religious feelings.” Finally, amendments to the Law on Broadcasting were passed, which increased the government’s control over the media, reduced their transparency and potentially eroded public trust in the media.

- Surveillance: In August 2015, the government created a new agency, the SSG, responsible for internal surveillance operations. The Law on Personal Data Protection was passed in March 2016, which allowed security services to conduct electronic surveillance with permission from the judiciary. Privacy watchdogs were troubled by how permissive the law was in granting the government access to data. In March 2017, the parliament adopted new surveillance regulations, establishing a new entity called the Operative Technical Agency (OTA), operating under the State Security Service, responsible for surveillance activity across computer and telecommunication networks, with authority to install clandestine applications on individuals' devices.

Civic space actors were the targets of 24 recorded instances of state-backed legal cases between January 2015 and March 2021, with the highest volume in 2019. Members of the political opposition were most frequently the defendants (Table 3). As shown in Figure 6, charges in these cases were less often directly (33 percent) tied to fundamental freedoms (e.g., freedom of speech, assembly). There were more indirect charges (58 percent) such as forgery and money laundering, often used throughout the region to discredit the reputations of civic space actors. There were a number of instances (3 cases) where we did not find sufficient detail to determine the nature of the charges.

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Georgia

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

|

Defendant Category |

Number of Cases |

|

Media/Journalist |

8 |

|

Political Opposition |

12 |

|

Formal CSO/NGO |

1 |

|

Individual Activist/Advocate |

2 |

|

Other Community Group |

1 |

|

Other |

1 |

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Georgia

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

2.2 Attitudes Toward Civic Space in Georgia

Georgian citizens were less interested in politics but surpassed their regional peers in other Europe and Eurasia countries in several common forms of political participation (e.g., demonstrations, strikes, boycotts, petitions) in two surveys conducted in 2014 and 2018. Generally low membership rates in voluntary organizations and low levels of confidence in institutions likely continues to have a chilling effect on Georgians’ civic participation, with religious organizations as a notable exception. Georgians’ willingness to engage in less political forms of civic life (e.g., volunteerism, charitable donations, helping strangers) generally improved over the last decade, reaching a high in 2020, before backtracking somewhat in 2021. In this section, we take a closer look at Georgian citizens’ interest in politics, participation in political action or voluntary organizations, and confidence in institutions. We also examine how Georgian involvement in less political forms of civic engagement—donating to charities, volunteering for organizations, helping strangers—has evolved over time.

2.2.1 Interest in Politics and Willingness to Act as Barometers of Georgian Civic Space

Sixty-one percent of Georgian respondents to the 2014 World Values Survey said they were disinterested in politics (Figure 7), but they surpassed their E&E regional peers in political participation. As a case in point: 21 percent of Georgians had previously participated in demonstrations (+13 percentage points ahead of the regional average) and an additional 17 percent said they would consider doing so in future. Notably, 30,000 Georgians joined anti-government protests in Tbilisi in November—a month prior to when the WVS was conducted—in opposition to a proposed Russian-Georgian agreement over Georgia’s Russia occupied territory of Abkhazia. [13] These protests were likely top-of-mind for Georgian respondents, possibly making them more open-minded to the idea of future demonstrations. Although less than 10 percent had signed petitions, strikes, or boycotts (Figure 8), Georgians still engaged in these activities at higher rates (+2-5 percentage points) than other E&E countries (Figure 9).

By 2018, however, Georgian respondents to the World Values Survey [14] reported declining rates of involvement in demonstrations (-9 percentage points) and even higher disinterest in politics (64 percent, +2 percentage points) than in 2014. [15] The muted enthusiasm in Georgia for joining protests is somewhat surprising in light of the ongoing White Noise Movement in 2018, though the rallies organized by the movement were on a much smaller scale than the 2014 protests in Tbilisi. One bright spot was an uptick in interest in other common forms of political participation including boycotts and petitions, +4 and +10 percentage points, respectively, since 2014. [16] Georgians still surpassed regional peers in their level of participation across all four types of political activities in 2018, but the gap had narrowed (+1 to +3 percentage points).

Figure 7. Interest in Politics: Georgian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2014 and 2018

Figure 8. Political Action: Georgian Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2014 versus 2018

Percentage of Respondents

Figure 9. Political Action: Participation by Georgian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2014 and 2018

Percentage of Respondents Reporting “Have Done”

Membership in voluntary organizations was lower among Georgians than their peers across the E&E region in 2014, with the notable exception of the church (Figure 10). Twenty-one percent of respondents identified themselves as members of a religious congregation (+11 percentage points above the regional average), while all other organization types had zero to two percent of respondents as members (-5 to -7 percentage points behind the regional average). [17]

Figure 10. Voluntary Organization Membership: Georgian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2014 and 2018

With citizens reluctant to join most forms of voluntary organizations (Table 4), religious institutions were an important backbone for Georgian civic space, particularly in light of low confidence in the country’s institutions (Table 5). In 2014, religious establishments were one of only a handful of institutions that enjoyed the confidence of over half of Georgian respondents (87 percent confident), along with the military (77 percent confident) and environmental organizations (53 percent confident). Comparatively, less than one third of Georgians were confident in the government or the press, trailing the regional average by 23-25 percentage points.

Georgians’ confidence in religious organizations declined by 10 percentage points in 2018, possibly due to a series of highly publicized scandals involving the clergy beginning in 2017, [18] and membership in these institutions dropped to 8 percent. Nevertheless, religious organizations still enjoyed the confidence of more than three-quarters of Georgian respondents. Although still trailing their E&E regional peers, Georgians’ membership in other voluntary organizations increased by 2 percentage points in 2018 and confidence in most institutions also grew between the survey waves. [19]

Table 4. Georgian Citizens’ Membership in Voluntary Organizations by Type, 2014 and 2018

|

Voluntary Organization |

Membership, 2014 |

Membership, 2018 |

Percentage Point Change |

|

Church or Religious Organization |

21% |

8% |

-13 |

|

Sport or Recreational Organization |

1% |

3% |

+2 |

|

Art, Music or Educational Organization |

2% |

5% |

+3 |

|

Labor Union |

1% |

4% |

+3 |

|

Political Party |

2% |

3% |

+2 |

|

Environmental Organization |

0% |

2% |

+2 |

|

Professional Association |

0% |

2% |

+2 |

|

Humanitarian or Charitable Organization |

0% |

2% |

+2 |

|

Consumer Organization |

0% |

2% |

+2 |

|

Self-Help Group, Mutual Aid Group |

0% |

2% |

+2 |

|

Other Organization |

1% |

2% |

+2 |

Table 5. Georgian Confidence in Key Institutions, 2014 and 2018

|

Institution |

Confidence, 2014 |

Confidence, 2018 |

Percentage Point Change |

|

Church or Religious Organization |

87% |

77% |

-10 |

|

Military |

78% |

78% |

0 |

|

Press |

22% |

28% |

+6 |

|

Labor Unions |

18% |

23% |

+5 |

|

Police |

50% |

57% |

+8 |

|

Courts |

33% |

39% |

+6 |

|

Government |

32% |

37% |

+5 |

|

Political Parties |

20% |

20% |

0 |

|

Parliament |

29% |

30% |

+1 |

|

Civil Service |

47% |

54% |

+7 |

|

Environmental Organizations |

53% |

49% |

-4 |

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

The Gallup World Poll’s (GWP) Civic Engagement Index affords an additional perspective on Georgian citizens’ attitudes towards less political forms of participation between 2010 and 2021. This index measures the proportion of citizens that reported giving money to charity, volunteering at organizations, and helping a stranger on a scale of 0 to 100. [20]

Georgia was among the region’s poorer performers at the start of the decade with civic engagement scores hovering around 19, as compared to the regional average of 25 points (Figure 11), largely driven by fairly low levels of charitable giving (3 percent), which trailed the regional average by 13 percentage points. [21] Following a few years of improvement, Georgia’s civic engagement experienced a sharp decline in 2016 across all three index measures. Most noticeably, the share of Georgians volunteering with organizations dropped from 18 to 9 percent compared to the previous year, with fewer respondents donating to charity (-4 percentage points) or helping a stranger (-3 percentage points). Beyond the scope of the index, Georgia’s 2016 parliamentary elections also attracted the lowest voter turnout in a decade. [22] Taken together, low rates of volunteerism and low political participation could speak to broader social conditions in the country fueling disengagement. [23]

Figure 11. Civic Engagement Index: Georgia versus Regional Peers

Later in the period, Georgia’s civic engagement experienced a resurgence, reaching its peak performance in 2020. Georgia’s 2020 index score improved by 13 points compared to the previous year, exceeding the regional mean by 2 percentage points. That year, 76 percent of Georgians helped a stranger and 34 percent volunteered their time (+16 percentage points compared to 2019). Georgia’s rate of charitable donations also improved by 4 percentage points to 9 percent, still trailing regional peers. This upward trend is consistent with improving civic engagement across the region and around the world as citizens rallied in response to COVID-19, even in the face of lockdowns and limitations on public gathering.

Nevertheless, these gains may not be sustainable. In 2021, Georgia’s Civic Engagement Index dropped again by 9 points, with declining rates of participation across all three index measures following an election in February, the arrest of Mikheil Saakashvili, and opposition parties boycotting Parliament. [24] These political shocks, and the stresses of the second year of the pandemic, may have had negative spillover effects on Georgian citizens’ interest in even less political forms of civic participation.

3. External Channels of Influence: Kremlin Civic Space Projects and Russian State-Run Media in Georgia

Foreign governments can wield civilian tools of influence such as money, in-kind support, and state-run media in various ways that disrupt societies far beyond their borders. They may work with the local authorities who design and enforce the prevailing rules of the game that determine the degree to which citizens can organize themselves, give voice to their concerns, and take collective action. Alternatively, they may appeal to popular opinion by promoting narratives that cultivate sympathizers, vilify opponents, or otherwise foment societal unrest. In this section, we analyze data on Kremlin financing and in-kind support to civic space actors or regulators in Georgia (section 3.1), as well as Russian state media mentions related to civic space, including specific actors and broader rhetoric about democratic norms and rivals (section 3.2).

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to Georgia’s Civic Space

The Kremlin supported 22 Georgian civic organizations via 46 civic space-relevant projects in Georgia from January 2015 to August 2021. Moscow prefers to directly engage and build relationships with individual civic actors, as opposed to investing in broader based institutional development which accounted for a mere 4 percent of its overtures (2 projects). The Kremlin’s interest in cultivating relationships with Georgian civic actors grew steadily from 2015 to 2019, with a decrease in 2020 and complete drop-off in 2021, likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 12). Kremlin-backed civic space projects centered on promoting Russian linguistic and cultural ties in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia, in line with Moscow’s emphasis on cultural promotion and occupied territories also observed elsewhere in the E&E region.

Figure 12. Russian Projects Supporting Georgian Civic Space Actors by Type

Number of Projects Recorded, January 2015–August 2021

The Kremlin routed its engagement in Georgia through 12 different channels (Figure 13), including government ministries, federal centers, language and culture-focused funds, charitable foundations, and the Russian Embassy in Sokhumi. The stated missions of these Russian government entities tend to emphasize themes such as education and culture promotion, patriotic celebrations of Russia’s military history, and security related issues. However, not all of these Russian state organs were equally important. Rossotrudnichestvo [25] and the Gorchakov Fund [26] supplied over 95 percent of all known Kremlin-backed support (21 organizations via 44 projects). Rossotrudnichestvo—an autonomous agency under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with a mandate to promote political and economic cooperation abroad—alone is associated with two-thirds of the overtures to Georgian civic actors (32 projects).

The Gorchakov Fund, which accounted for one-quarter of all Russian state-backed civic space projects in Georgia identified between 2015 and 2021, typically provides projectized support to non-governmental organizations to promote Russian culture and Russia’s image abroad. In a departure from its cooperative strategy elsewhere in the region, the Gorchakov Fund was the sole Russian sponsor for all of its projects in Georgia. Comparatively, Rossotrudnichestvo hewed more closely to its usual modus operandi, [27] coordinating its support to Georgian civic space actors with seven other Russian organizations. This included one private sector actor, Ostelcom, a subsidiary of the Russian mobile phone operator MegaFon PJSC that co-sponsored the festival of Russian Culture in Tskhinvali with Rossotrudnichestvo and the Union of Russian Citizens in Georgia’s Russia-occupied South Ossetia in April 2018.

Security-focused organizations, namely the Russian Ministry of Defense and Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, were each involved in supporting one project with civic space actors in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia. The Ministry of Defense pushed the boundaries of Rossotrudnichestvo’s public diplomacy mandate when they co-hosted a ten-day youth military training camp in Gaudata. The two organizations also acted as a conduit for Russian military-patriotic public associations, namely the Sochi Branch of the All-Russian Military-Patriotic public movement “Yunarmiya,” the All-Russian public Association "Combat Brotherhood,” and the Victory Commanders Memorial Fund.

Figure 13. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Georgian Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

3.1.1 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Georgia’s Civic Space

Civil society organizations (CSOs) were most frequently named as beneficiaries of Russian state-backed overtures, associated with 59 percent of identified projects (27 projects). Other non-governmental recipients of the Kremlin’s attention included compatriot unions for the Russian diaspora in Georgia and de facto authorities in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia.

“The Joint Information-Coordination Center of the Internal Affairs Ministries of Russia and Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia” was also identified as receiving support from the Kremlin, relevant to civic space. The facility was greenlit in July 2015 to facilitate cooperation between Russia and the de facto authorities in Georgia’s Russia occupied Abkhazia. The pursuit of this center was met with some pushback in 2015, as many feared it would bring in over 400 Russian personnel. The parliament in Sokhumi ratified the foundation of the center in July 2017, though it appears that funding for the center was still being discussed as of March 2019. [28]

Nearly all of the Georgian recipient organizations identified worked in the education and culture sector (19 organizations), many with an emphasis on promoting Russian language and history. Elsewhere in the region the Kremlin has engaged with civic actors working in the religious sphere, or otherwise folded Orthodox religious themes into educational or cultural events, such as Rossotrudnichestvo supporting children’s art celebrations around Orthodox holidays. In Georgia, however, none of the Kremlin’s activities relied on religion as explicitly, perhaps stemming from the rift between the Georgian and Russian Orthodox Churches, as well as an attempt by the Orthodox Church in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia to establish itself as an independent institution. [29] This rift may have reduced the number of religious organizations willing to partner with Russian actors.

Seven beneficiary organizations (32 percent of identified organizations) worked with Georgian youth on a wide range of activities. In Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia, Russian organizations sponsored general outreach events, including chess and checkers competitions, a “Youth Against Drugs” sports relay, and a number of competitions in conjunction with the Triathlon Federation. The Kremlin also supported more politically oriented youth trainings, many in Tbilisi. The Gorchakov Fund backed a series of political science roundtables at the Center for Cultural Relations “Caucasian House” in 2015 and 2016. In 2018, the Fund wrote a grant to the Union of Russian Youth of Georgia to host a forum for young NGO leaders “People’s Diplomacy—Dialogue of Compromises” in October.

Consistent with the Kremlin’s revealed interest in training of future military and civic leaders elsewhere in the E&E region, Russian actors also supported a ten-day military training camp in Gudauta in August 2018. Although the stated goal of the event was to “strengthen in the minds of adolescents the rejection of violence,” the actual content was less benign, as youth in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia received training in hand-to-hand combat and reconnaissance.

The Kremlin also partnered with seven compatriot unions [30] throughout Georgia, based in Ochamchire, Sokhumi, Tbilisi, and Tskhinvali. Apart from the NGO leaders forum in Tbilisi discussed above, Russia’s support to compatriot unions mainly centered on music festivals and holiday commemorations, such as the distribution of St. George’s ribbons with the Russian Community of the Ochamchire and Gali districts in May 2020. Most of these events were based in Georgia’s two Russia-occupied territories, though the presence of the Union of Russian Youth of Georgia, in Tbilisi, indicates that Russian compatriot unions are not restricted to the occupied territories.

Geographically, the majority of Russian-state overtures were oriented towards Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia (28 projects) and Georgia’s Russia-occupied South Ossetia (10 projects). Three Rossotrudnichestvo-backed events, related to distributing St. George’s ribbons in partnership with local compatriot unions and the youth NGO Open Palm, occurred in both regions simultaneously. That said, there was a slight difference between projects in the two separatist regions. Russian projects specifically in Akhalgori and Tskhinvali, were focused on events celebrating Russian language and music, many conducted with the Association of Teachers of Russian Language and Literature of [Georgia’s Russia-occupied] South Ossetia (APRYAL SO). Activities in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia were more varied, including sports, the aforementioned military training camp, and the proposed Joint Information Coordination Center between the Internal Affairs Ministries of Russia and the de facto authorities of Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia.

The Kremlin’s greater emphasis on Georgia’s occupied territories is consistent with its playbook in other E&E countries but may also be a reality of navigating anti-Russian public sentiment among Georgians. Nevertheless, animosity towards Russia did not deter all activity in Tbilisi-controlled Georgia. The Gorchakov Fund still supported 12 projects in Tbilisi and Batumi (Figure 14). These events were primarily hosted by the Center for Cultural Relations "Caucasian House,” the Georgian-Russian Public Center named after E.M. Primakov, and the Union of Russian Youth of Georgia.

Figure 14. Locations of Russian Support to Georgian Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

Yet, neither is Russia’s approach entirely monolithic. In a departure from its promotion of Russian language throughout much of the E&E region, the Gorchakov Fund announced in July 2019 that it would award the Center for the Defense of the Georgian Language a grant for a youth expert meeting in the first half of 2020. The impetus for this grant may have been defensive, rather than proactive, as the Kremlin attempted to quell public outrage over Russian replacing Georgian as the medium of instruction for schools in Georgia’s Russia-occupied South Ossetia. The Gorchakov Fund and its partners canceled many events during the COVID-19 pandemic, so it is unclear if the event took place, but this grant may indicate a new openness to the Kremlin engaging with national languages in the E&E region, rather than solely promoting Russian.

3.1.2 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Georgia's Civic Space

As seen elsewhere in the E&E region, the primary mode of Russian support in Georgia does not appear to be direct transfers of funding, but rather non-financial “support.” Only four of the projects identified explicitly described recipients receiving grants, and all were awarded by the Gorchakov Fund. Instead, the Russian government relies much more extensively on supplying various forms of non-financial “support” such as training, technical assistance, and other in-kind contributions to its Georgian partners.

One of the main modes of Russian assistance was through supporting local conferences and round tables. The Kremlin’s contributions to local conferences and events across the region is typically in the form of space, materials, or other logistical and technical contributions to local partners via organs such as Rossotrudnichestvo or the Gorchakov Fund. Most of these events in Georgia focused on promoting Russian language and culture and included musical concerts and book donations during the holidays.

While most of the Georgian organizations Russia partners with appear to have a general audience, nearly one-third of the identified projects (15 projects) were designed with youth as the target demographic. Elsewhere in the region, Russian events tend to focus on children’s events, but in Georgia the Kremlin tends to focus events more on teenagers and young adults. These events include roundtables of “young specialists” and more general political skills training for youth, ultimately preparing them for leadership positions in civil society. These events also include the more troubling paramilitary youth camp mentioned above. Russian actors have also supported military education for youth in Belarus, Moldova’s Transnistria region, and Serbia.

Beginning in 2018, Rossotrudnichestvo sponsored a number of sports events in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia, primarily in conjunction with the Triathlon Federation. The first of these events was a bike ride in May 2018 commemorating the “independence” of the occupied territory in the 1992-1993 war. In 2019, these events shifted from laying wreaths to sponsoring triathlons and duathlons in Sokhumi. While less explicitly political, Rossotrudnichestvo’s engagement with civic organizations in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia appears to have deepened over the past half decade and taken on more logistically complex events

3.2 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced Georgian civic actors 622 times from January 2015 to March 2021. Nearly three-quarters of these mentions (457 instances) were of domestic actors, while the remaining 27 percent (165 instances) focused on foreign and intergovernmental actors operating in Georgia’s civic space. In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of Georgian citizens, we also analyzed 581 mentions of five keywords in conjunction with Georgia: North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO, the United States, the European Union, democracy, and the West. In this section, we examine Russian state media coverage of domestic and external civic space actors, how this has evolved over time, and the portrayal of democratic institutions and Western powers to Georgian audiences.

3.2.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Georgian Civic Space Actors

Over half (51 percent) of Russian media mentions pertaining to domestic actors in Georgia’s civic space referred to specific groups by name. Domestic actors, writ large, represent a diverse cross-section of organizational types—from political parties to civil society organizations and media outlets. Political parties were the most frequently mentioned domestic organizations (Table 6). Three Georgian parties accounted for the vast majority of these mentions: the United National Movement (55 mentions), the Democratic Movement-United Georgia (45 mentions), and Georgia Dream (36 mentions).

Russian state media mentions of specific Georgian civic actors were most often neutral (86 percent) in tone. The remaining coverage was mostly negative (11 percent), with only 6 mentions (3 percent) receiving positive coverage. Negative coverage was evenly distributed across different types of civic organizations, with the majority of negative mentions split between Georgian media outlet Rustavi-2 which shifted from opposition-aligned to Georgia Dream-aligned (10 negative mentions), the Richard G. Lugar Center for Public Health Research (4 negative mentions), and the United National Movement (6 negative mentions).

The negative sentiment towards Rustavi-2 was a reaction to Giorgi Gabunia, the host of “Post Scriptum,” delivering a monologue insulting Russian President Vladimir Putin on his show. Russian state media condemned the Georgian TV channel and Gabunia himself. This episode is illustrative of “Putinism,” as Russian state coverage attempted to protect Putin’s image in Georgia and defended the reputation of the president. This dynamic has not been as explicit in Russian state media coverage of other E&E countries.

The Richard G. Lugar Center for Public Health Research, now fully owned and operated by the Georgian government, was a favorite target for Russian state media-amplified conspiracy theories (4 negative mentions) seeking to discredit Western countries, similar to dynamics in North Macedonia. Russian state media implied that the U.S.-funded center was “a cover for a bioweapons laboratory” [31] which was “conducting highly suspicious experiments on mortally ill patients.” [32] Finally, as seen in other countries in the region, pro-European political parties also attracted negative coverage.

The 6 positive mentions were divided among 4 civic actors: the pro-Russian Alliance of Patriots of Georgia (2 positive mentions), the Georgian Orthodox Church (2 mentions), the opposition party Amtsakhara in Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia (1 positive mention), and the pro-Russian “Society of Tsar Irakly II” (1 positive mention). The contrast between the positive coverage of pro-Russian movements and political parties and the negative coverage of pro-European parties is noteworthy.

Aside from these named organizations, TASS and Sputnik made 222 more generalized references to domestic Georgian non-governmental organizations, protesters, opposition activists, or other informal groups during the same period. The sentiment of these mentions was predominantly neutral (71 percent) or negative (28 percent).

Table 6. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in Georgia by Sentiment

|

Domestic Civic Group |

Extremely Negative |

Somewhat Negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat Positive |

Grand Total |

|

Opposition |

6 |

15 |

47 |

1 |

69 |

|

United National Movement (UNM) Party |

0 |

6 |

49 |

0 |

55 |

|

Protesters |

0 |

10 |

40 |

1 |

51 |

|

Democratic Movement - United Georgia |

0 |

0 |

45 |

0 |

45 |

|

Georgia Dream (GD) Party |

0 |

0 |

36 |

0 |

36 |

3.2.2 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in Georgian Civic Space

Russian state media dedicated the remaining mentions (165 instances) to external actors in Georgia’s civic space, including 12 intergovernmental organizations (89 mentions), 34 foreign organizations by name (54 mentions), as well as 9 general foreign actors (22 mentions) such as foreign journalists and Russian NGOs. The most frequently mentioned external actors were formal Western organizations (Table 7). Russian state media mentions of external actors, both named and unnamed, was highly neutral (85 percent) in tone. The remaining coverage was mostly negative (15 percent).

Similar to the domestic civic actors, references to external actors spiked around the 2019 protests. The initial trigger for the protests, Russian Duma member Sergei Gavrilov speaking from the Georgian Speaker’s seat, was facilitated by the Interparliamentary Assembly on Orthodoxy (IAO), which explains the high volume of mentions of the IAO. The remaining top mentions are predominantly Western intergovernmental organizations, and they account for the majority of negative mentions. Similar to the coverage of protests in North Macedonia and Belarus, Russian state media accused Western institutions of inciting the protests and, to a lesser degree, continued to push conspiracy theories about the Open Society Foundation manipulating civic actors in Georgia. Once again, this negative coverage is consistent with the Russian media’s attitude towards Western institutions throughout the E&E region.

Table 7. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Georgia by Sentiment

|

External Civic Actors |

Extremely Negative |

Somewhat Negative |

Neutral |

Grand Total |

|

Interparliamentary Assembly on Orthodoxy |

0 |

0 |

44 |

44 |

|

Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) / Including ODIHR |

0 |

2 |

13 |

15 |

|

European Union / Including European Parliament, European Commission, European Court of Human Rights |

0 |

1 |

12 |

14 |

|

NATO |

3 |

3 |

3 |

9 |

|

Rossiya-24 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

9 |

3.2.3 Russian State Media’s Focus on Georgia’s Civic Space over Time

As a general rule, Russian state media mentions of civic space actors tend to spike around specific events within E&E countries. This dynamic is even more pronounced in Georgia (Figure 15), as forty-three percent of mentions for the entire tracking period (January 2015–March 2021) occurred in just two months: June to July 2019. Although there were also minor spikes in reporting associated with parliamentary and presidential elections in October 2016 and October 2018, respectively, Russian state media coverage of the 2019 protests dwarfed these other events. The stronger anti-Russian nature of the 2019 protests in comparison to past anti-government protest movements likely contributed to the increased coverage by Russian state-owned media.

The initial trigger for the 2019 protests was Duma member Gavrilov’s visit to the Interparliamentary Assembly on Orthodoxy; however, unrest surged again in November 2019, following broken promises of electoral reform by the ruling Georgian Dream party. The uptick in mentions in November and December 2019 documents the renewed protests, after the initial spike in June and July 2019.

While Russian state media reporting remained mostly neutral during the protests, the coverage of Georgian civic actors saw a slightly higher percentage of negative sentiment over the June-July 2019 period ,as compared to the overall period of interest. The negative coverage of these protests is consistent with trends observed in Moldova, Belarus, and Armenia, likely a reflection of the Kremlin’s anxiety about potential color revolutions in countries along Russia’s border. Since the initial trigger for the protests were connected to a Russian politician, the protests were perceived to be “anti-Russian,” which may have attracted more negative coverage as Russian media sought to control the narrative.

Figure 15. Russian State Media Mentions of Georgian Civic Space Actors

Number of Mentions Recorded

3.2.4 Russian State Media Coverage of Western Institutions and Democratic Norms

In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of Georgia’s citizens, we analyzed the frequency and sentiment of coverage related to five keywords in conjunction with Georgia. [33] Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced all five keywords from January 2015 to March 2021 (Figure 16). Russian state media mentioned the European Union (124 instances), the United States (195 instances), NATO (189 instances), the “West” (67 instances), and democracy (6 instances) with reference to Georgia during this period (Table 8). Just over half (52 percent) of these mentions (301 instances) were negative, while an extremely small share was positive (6 percent).

Figure 16. Keyword Mentions by Russian State Media in Relation to Georgia

Number of Unique Keyword Instances of NATO, the U.S., the EU, Democracy, and the West in Russian State Media

Table 8. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

|

Keyword |

Extremely negative |

Somewhat negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat positive |

Extremely positive |

Grand Total |

|

NATO |

76 |

59 |

37 |

15 |

2 |

189 |

|

European Union |

7 |

15 |

91 |

9 |

2 |

124 |

|

United States |

60 |

36 |

94 |

5 |

0 |

195 |

|

Democracy |

2 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

West |

22 |

24 |

19 |

2 |

0 |

67 |

NATO and the European Union were the second and third most frequently mentioned keywords in reference to Georgia. Tbilisi’s aspirations to join the two membership blocs was the most common recurring topic across both keywords. The Kremlin targeted a higher proportion of negative coverage (71 percent of mentions) towards NATO relative to the EU, positioning NATO’s joint exercises and deepening military cooperation with Georgia as provoking instability in the region, [34] in “violation of NATO’s promises” not to expand eastward, [35] and the main impediment to improved Moscow-Tbilisi relations. [36] As observed elsewhere in the E&E region, state media portrayed Russia as defending the rights and interests of occupied territories, with Moscow, Sokhumi (Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia), and Tskhinvali (Georgia’s Russia-occupied South Ossetia) as united in their view of “Georgia’s deepening cooperation with NATO amid Tbilisi’s unfriendly rhetoric…as a real threat to regional security” [37] For example, one Sputnik article characterized Russia as the responsible actor in the face of NATO’s unwise overtures:

[Referring to Russia-occupied territories in Georgia] "It is an absolutely irresponsible position. It is just a threat to peace. This can undoubtedly lead to a potential conflict because we consider Abkhazia and South Ossetia independent states. We have friendly relations with these states. Our military bases are located there……" The Russian prime minister noted that NATO’s decision to accept Georgia might lead to very grave consequences." [38]

Comparatively, Russian media coverage of the EU in relation to North Macedonia was more often neutral (73 percent) and much less negative (18 percent). Nevertheless, Kremlin-affiliated media were fairly consistent in articulating Moscow’s position that Georgia’s membership in neither bloc was acceptable. [39] For example, towards the end of the period, one Sputnik article quoted Andrey Rudenko, Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister, as saying that “Georgia’s aspirations to become a member of NATO and the European Union are an unjustified choice that should not be accomplished.” [40] More negative mentions of the EU also questioned its credibility in light of its “slavish adherence to the U.S. [foreign policy] position” [41] and deemed its collusion with Georgia in blocking Russia’s draft resolution calling for sanctions relief amid the coronavirus pandemic as “immoral” and “irresponsible.” [42]

Russian state media mentioned the United States most frequently of the five keywords in relation to Georgia, with coverage roughly split between negative (49 percent) and neutral (48 percent) sentiment. As mentioned previously, the U.S. attracted the most negative coverage related to the Richard Lugar Public Health Research Center on the outskirts of Tbilisi, which Russian state media have decried as “a secret [U.S.] biological weapons laboratory” [43] which uses Georgian partners “as guinea pigs” to conduct lethal experiments [44] in violation of international conventions. [45] Other negative coverage was more predictably consistent with the Kremlin’s preferred narratives elsewhere in the region, accusing the U.S. of intervening in Georgia’s internal affairs by “manually managing political processes and dictating how the authorities should function” [46] and spreading “anti-Russian sentiments to reduce Russia’s influence.” [47]

Particularly relevant to civic space, Russian state media evoked neo-Nazi terminology [48] to portray U.S.-backed democracy promotion efforts as promoting an “American brand of Lebensraum” to manipulate Georgians to advance U.S. and European “crypto-imperial policy.” [49] Similar to dynamics in other E&E countries, Russian state media used “the West” (69 percent negative mentions) to inject fear about the motives of the U.S. and Europe writ large, warning against Western attempts to create “dependency” and instigate regime changes by “sparking allegedly spontaneous civic unrest,” [50] attempts to “fan anti-Russian hysteria,” “saturate the region with weapons,” and “pull Georgia into NATO.” [51]

4. Conclusion

The data and analysis in this report reinforces a sobering truth: Russia’s appetite for exerting malign foreign influence abroad is not limited to Ukraine, and its civilian influence tactics are already observable in Georgia and elsewhere across the E&E region. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see clearly how the Kremlin invested its media, money, and in-kind support to promote pro-Russian sentiment within Georgia and discredit voices wary of its regional ambitions.

The Kremlin was adept in deploying multiple tools of influence in mutually reinforcing ways to amplify the appeal of closer integration with Russia, raise doubts about the motives of the U.S., EU, and NATO, as well as legitimize its actions as necessary to protect the region’s security from the disruptive forces of democracy. It oriented a substantial amount of Russian state media coverage to deter Georgia’s aspirations to join NATO and the EU, promote pro-Kremlin voices, and undercut the credibility of pro-European or Western-affiliated organizations. Russia also paid outsized attention to building ties with Georgia’s Russia-occupied Abkhazia, similar to its emphasis on occupied and autonomous territories elsewhere in the region.

Taken together, it is more critical than ever to have better information at our fingertips to monitor the health of civic space across countries and over time, reinforce sources of societal resilience, and mitigate risks from autocratizing governments at home and malign influence from abroad. We hope that the country reports, regional synthesis, and supporting dataset of civic space indicators produced by this multi-year project is a foundation for future efforts to build upon and incrementally close this critical evidence gap.

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

In this section, we provide a brief overview of the data and methods used in the creation of this country report and the underlying data collection upon which these insights are based. More in-depth information on the data sources, coding, and classification processes for these indicators is available in our full technical methodology available on aiddata.org

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

AidData collected and classified unstructured information on instances of harassment or violence, restrictive legislation, and state-backed legal cases from three primary sources: (i) CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Georgia; (ii) RefWorld database of documents and news articles pertaining to human rights and interactions with civilian law enforcement in Georgia operated by UNHCR; and (iii) Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. AidData supplemented this data with country-specific information sources from media associations and civil society organizations who report on such restrictions. Restrictions that took place prior to January 1, 2015 or after March 31, 2021 were excluded from data collection. It should be noted that there may be delays in reporting of civic space restrictions. More information on the coding and classification process is available in the full technical methodology documentation.

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

Survey data on citizen perceptions of civic space were collected from three sources: the World Values Survey Wave 6, the Joint European Values Study and World Values Survey Wave 2017-2021, the Gallup World Poll (2010-2021). These surveys capture information across a wide range of social and political indicators. The coverage of the three surveys and the exact questions asked in each country vary slightly, but the overall quality and comparability of the datasets remains high.

The fieldwork for WVS Wave 6 in Georgia was conducted during December 2014 with a nationally representative sample of 1202 randomly selected adults residing in private homes, regardless of nationality or language. [52] The documentation does not specify the language that the survey was conducted in. Research team provided an estimated error rate of 2.9%. This weight is provided as a standard version for consistency with previous releases.” [53] The E&E region countries included in WVS Wave 6, which were harmonized and designed for interoperable analysis, were Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Ukraine. Regional means for the question “How interested you have been in politics over the last 2 years?” were first collapsed from “Very interested,” “Somewhat interested,” “Not very interested,” and “Not at all interested” into the two categories: “Interested” and “Not interested.” Averages for the region were then calculated using the weighted averages from the seven countries.

Regional means for the WVS Wave 6 question “Now I’d like you to look at this card. I’m going to read out some different forms of political action that people can take, and I’d like you to tell me, for each one, whether you have actually done any of these things, whether you might do it or would never, under any circumstances, do it: Signing a petition; Joining in boycotts; Attending lawful demonstrations; Joining unofficial strikes” were calculated using the weighted averages from the seven E&E countries as well.

The membership indicator uses responses to a WVS Wave 6 question which lists several voluntary organizations (e.g., church or religious organization, political party, environmental group). Respondents to WVS 6 could select whether they were an “Active member,” “Inactive member,” or “Don’t belong.” The values included in the profile are weighted in accordance with WVS recommendations. The regional mean values were calculated using the weighted averages from the seven countries included in a given survey wave. The values for membership in political parties, humanitarian or charitable organizations, and labor unions are provided without any further calculation, and the “Other community group” cluster was calculated from the mean of membership values in “Art, music or educational organizations,” “Environmental organizations,” “Professional associations,” “Church or other religious organizations,” “Consumer organizations,” “Sport or recreational associations,” “Self-help or mutual aid groups,” and “Other organizations.”

The confidence indicator uses responses to an WVS Wave 6 question which lists several institutions (e.g., church or religious organization, parliament, the courts and the judiciary, the civil service). Respondents to WVS 6 surveys could select how much confidence they had in each institution from the following choices: “A great deal,” “Quite a lot,” “Not very much,” or “None at all.” The “A great deal” and “Quite a lot” options were collapsed into a binary “Confident” indicator, while “Not very much” and “None at all” options were collapsed into a “Not confident” indicator. [54]

The fieldwork for EVS Wave 5 in Georgia was conducted in Georgian, Russian, Azerbaijani and Armenian between January and March 2018 with a nationally representative sample of 2194 randomly selected adults residing in private homes, regardless of nationality or language. [55] The research team did not provide an estimated error rate for the survey data after applying a weighting variable “computed using the marginal distribution of age, sex, educational attainment, and region. This weight is provided as a standard version for consistency with previous releases.” [56]

The E&E region countries included in the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 dataset, which were harmonized and designed for interoperable analysis, were Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, and Ukraine. Regional means for the question “How interested have you been in politics over the last 2 years?” were first collapsed from “Very interested,” “Somewhat interested,” “Not very interested,” and “Not at all interested” into the two categories: “Interested” and “Not interested.” Averages for the region were then calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen countries.

Regional means for the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 question “Now I’d like you to look at this card. I’m going to read out some different forms of political action that people can take, and I’d like you to tell me, for each one, whether you have actually done any of these things, whether you might do it or would never, under any circumstances, do it: Signing a petition; Joining in boycotts; Attending lawful demonstrations; Joining unofficial strikes” were calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen E&E countries as well.

The membership indicator uses responses to a Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 question which lists several voluntary organizations (e.g., church or religious organization, political party, environmental group, etc.). Respondents to WVS 7 could select whether they were an “Active member,” “Inactive member,” or “Don’t belong.” The EVS 5 survey only recorded a binary indicator of whether the respondent belonged to or did not belong to an organization. For our analysis purposes, we collapsed the “Active member” and “Inactive member” categories into a single “Member” category, with “Don’t belong” coded to “Not member.” The values included in the profile are weighted in accordance with WVS and EVS recommendations. The regional mean values were calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen countries included in a given survey wave. The values for membership in political parties, humanitarian or charitable organizations, and labor unions are provided without any further calculation, and the “Other community group” cluster was calculated from the mean of membership values in “Art, music or educational organizations,” “Environmental organizations,” “Professional associations,” “Church or other religious organizations,” “Consumer organizations,” “Sport or recreational associations,” “Self-help or mutual aid groups,” and “Other organizations.”

The confidence indicator uses responses to a Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 question which lists several institutions (e.g., church or religious organization, parliament, the courts and the judiciary, the civil service, etc.). Respondents to the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 surveys could select how much confidence they had in each institution from the following choices: “A great deal,” “Quite a lot,” “Not very much,” or “None at all.” The “A great deal” and “Quite a lot” options were collapsed into a binary “Confident” indicator, while “Not very much” and “None at all” options were collapsed into a “Not confident” indicator. [57]