Civic Space Country Report

Belarus: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence

Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, Lincoln Zaleski

April 2023

[Skip to Table of Contents] [Skip to Chapter 1]Executive Summary

This report surfaces insights about the health of Belarus’ civic space and vulnerability to malign foreign influence in the lead up to Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Research included extensive original data collection to track Russian state-backed financing and in-kind assistance to civil society groups and regulators, media coverage targeting foreign publics in the region, and indicators to assess domestic attitudes to civic participation and restrictions of civic space actors. Crucially, this report underscores that the Kremlin’s influence operations were not limited to Ukraine alone and illustrates its use of civilian tools in Belarus to co-opt support and deter resistance to its regional ambitions.

The analysis was part of a broader three-year initiative by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to produce quantifiable indicators to monitor civic space resilience in the face of Kremlin influence operations over time (from 2010 to 2021) and across 17 countries and 7 occupied or autonomous territories in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). Below we summarize the top-line findings from our indicators on the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Belarus, as well as channels of Russian malign influence operations:

- Restrictions of Civic Actors: Belarus accounted for the largest volume of restrictions (2,146) initiated against civic space actors in the E&E region between January 2015 and March 2021, driven by high instances of both harassment or violence (46 percent of instances) and state-backed legal cases (53 percent of instances). Thirty-one percent of restrictions were recorded in 2020, related to the presidential election, with the upsurge continuing into the first quarter of 2021 which alone accounted for 262 cases. Political opposition members were most frequently targeted, and the Belarusian government was the primary initiator. The Russian government was involved in four instances of restrictions of civic space actors and the Ukrainian government in one case.

- Attitudes Towards Civic Participation: Belarusians tended to report higher interest in politics than their regional peers, holding relatively steady (41-43 percent) between 2011 and 2018. This interest in politics has not led to high levels of civic participation, however. In 2018, Belarusians had extremely low rates of participation in civic activities, trailing most other countries in the region in their willingness to engage in demonstrations, strikes, boycotts, or petitions. Membership in all types of voluntary organizations has declined since 2011. Even outside of the political arena, far fewer Belarusians donated to charities, helped strangers or volunteered with organizations in 2019 than 2010, plummeting to the bottom of the rankings in the region’s Civic Engagement Index.

- Russian-backed Civic Space Projects: The Kremlin supported 21 Belarusian civic organizations via 30 civic space-relevant projects between January 2015 to August 2021. The Russian government routed its engagement in Belarus through 14 different state channels; however, the Gorchakov Fund and Rossotrudnichestvo alone supplied over four-fifths of all identified projects. The Kremlin’s cooperation activities more heavily emphasized Russian-Belarusian integration and promoted the framework of the Union State. Youth-focused programming was a common strategy, from general patriotic education to more intentional efforts to mobilize their support for integration.

- Russian State-run Media: Belarus was a popular target audience for Russian state media, capturing 12 percent of the Kremlin’s media mentions across the region and lagging only Ukraine. The preponderance of civic actor mentions (1,547 instances) coincided with the 2020 presidential elections and anti-government protests, with an uptick in coverage continuing into early 2021. Three-quarters of these mentions were of domestic actors, most often formal civil society organizations and media outlets, with the remainder including references to intergovernmental and foreign organizations operating in Belarus’ civic space. Russian media coverage of these civic space actors, as well as democratic norms and rivals (1,195 mentions), became increasingly negative as the Kremlin grew concerned of a potential color revolution and losing a staunch pro-Russia ally in President Lukashenko.

Table of Contents

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Belarus

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Belarus: Targets, Initiators, Trends Over Time

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

2.2 Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Belarus

2.2.1 Interest in Politics, Willingness to Act, and Membership in Voluntary Organizations

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to Belarusian Civic Space

3.1.1 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Belarusian Civic Space

3.1.2 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Belarusian Civic Space

3.2 Russian Media Mentions Related to Civic Space Actors and Democratic Rhetoric

3.2.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Belarusian Civic Space Actors

3.2.2 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in Belarusian Civic Space

3.2.3 Russian State Media’s Focus on Belarus’s Civic Space over Time

3.2.4 Russian State Media Coverage of Western Institutions and Democratic Norms

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

5.3 Russian Financing and In-kind Support to Civic Space Actors or Regulators

5.4 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors and Democratic Rhetoric

Figures and Tables

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of Belarusian Civic Space Actors

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Belarus

Figure 2. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Belarus by Initiator

Figure 3. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Belarus

Figure 4. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Belarus by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Figure 5. Threatened versus Acted-on Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Belarus

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Belarus

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Belarus

Figure 7. Interest in Politics: Belarusian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2018

Figure 8. Political Action: Belarusian Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2018

Figure 9. Political Action: Participation by Belarusian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2018

Table 4. Belarusian Citizens’ Membership in Voluntary Organizations by Type, 2011 and 2018

Table 5. Belarusian Confidence in Key Institutions, 2011 and 2018

Figure 11. Civic Engagement Index: Belarus versus Regional Peers

Figure 12. Russian Projects Supporting Belarusian Civic Space Actors by Type

Figure 13. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Belarusian Civic Space

Figure 14. Locations of Russian Support to Belarusian Civic Space

Table 6. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in Belarus by Sentiment

Table 7. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Belarus by Sentiment

Figure 15. Russian State Media Mentions of Belarusian Civic Space Actors

Table 8. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

Figure 16. Keyword Mentions by Russian State Media in Relation to Belarus

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, and Lincoln Zaleski. John Custer, Sariah Harmer, Parker Kim, and Sarina Patterson contributed editing, formatting, and supporting visuals. Kelsey Marshall and our research assistants provided invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report including: Jacob Barth, Kevin Bloodworth, Callie Booth, Catherine Brady, Temujin Bullock, Lucy Clement, Jeffrey Crittenden, Emma Freiling, Cassidy Grayson, Annabelle Guberman, Sariah Harmer, Hayley Hubbard, Hanna Kendrick, Kate Kliment, Deborah Kornblut, Aleksander Kuzmenchuk, Amelia Larson, Mallory Milestone, Alyssa Nekritz, Megan O’Connor, Tarra Olfat, Olivia Olson, Caroline Prout, Hannah Ray, Georgiana Reece, Patrick Schroeder, Samuel Specht, Andrew Tanner, Brianna Vetter, Kathryn Webb, Katrine Westgaard, Emma Williams, and Rachel Zaslavsk. The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

This research was made possible with funding from USAID's Europe & Eurasia (E&E) Bureau via a USAID/DDI/ITR Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) cooperative agreement (AID-A-12-00096). The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

A Note on Vocabulary

The authors recognize the challenge of writing about contexts with ongoing hot and/or frozen conflicts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consistently label groups of people and places for the sake of data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that terminology is political, but our use of terms should not be construed to mean support for one faction over another. For example, when we talk about an occupied territory, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the government in the capital. Or, when we analyze the de facto authorities’ use of legislation or the courts to restrict civic action, it is not to grant legitimacy to the laws or courts of separatists, but rather to glean meaningful insights about the ways in which institutions are co-opted or employed to constrain civic freedoms.

Citation

Custer, S., Mathew, D., Burgess, B., Dumont, E., Zaleski, L. (2023). Belarus: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence. April 2023. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William and Mary.

1. Introduction

How strong or weak is the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Belarus? To what extent do we see Russia attempting to shape civic space attitudes and constraints in Belarus to advance its broader regional ambitions? Over the last three years, AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—has collected and analyzed vast amounts of historical data on civic space and Russian influence across 17 countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). [1] In this country report, we present top-line findings specific to Belarus from a novel dataset which monitors four barometers of civic space in the E&E region from 2010 to 2021 (see Table 1). [2]

For the purpose of this project, we define civic space as: the formal laws, informal norms, and societal attitudes which enable individuals and organizations to assemble peacefully, express their views, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. [3] Here we provide only a brief introduction to the indicators monitored in this and other country reports. However, a more extensive methodology document is available via aiddata.org which includes greater detail about how we conceptualized civic space and operationalized the collection of indicators by country and year.

Civic space is a dynamic rather than static concept. The ability of individuals and organizations to assemble, speak, and act is vulnerable to changes in the formal laws, informal norms, and broader societal attitudes that can facilitate an opening or closing of the practical space in which they have to maneuver. To assess the enabling environment for Belarusian civic space, we examined two indicators: restrictions of civic space actors (section 2.1) and citizen attitudes towards civic space (section 2.2). Because the health of civic space is not strictly a function of domestic dynamics alone, we also examined two channels by which the Kremlin could exert external influence to dilute democratic norms or otherwise skew civic space throughout the E&E region. These channels are Russian state-backed financing and in-kind support to government regulators or pro-Kremlin civic space actors (section 3.1) and Russian state-run media mentions related to civic space actors or democracy (section 3.2).

Since restrictions can take various forms, we focus here on three common channels which can effectively deter or penalize civic participation: (i) harassment or violence initiated by state or non-state actors; (ii) the proposal or passage of restrictive legislation or executive branch policies; and (iii) state-backed legal cases brought against civic actors. Citizen attitudes towards political and apolitical forms of participation provide another important barometer of the practical room that people feel they have to engage in collective action related to common causes and interests or express views publicly. In this research, we monitored responses to citizen surveys related to: (i) interest in politics; (ii) past participation and future openness to political action (e.g., petitions, boycotts, strikes, protests); (iii) trust or confidence in public institutions; (iv) membership in voluntary organizations; and (v) past participation in less political forms of civic action (e.g., donating, volunteering, helping strangers).

In this project, we also tracked financing and in-kind support from Kremlin-affiliated agencies to: (i) build the capacity of those that regulate the activities of civic space actors (e.g., government entities at national or local levels, as well as in occupied or autonomous territories ); and (ii) co-opt the activities of civil society actors within E&E countries in ways that seek to promote or legitimize Russian policies abroad. Since E&E countries are exposed to a high concentration of Russian state-run media, we analyzed how the Kremlin may use its coverage to influence public attitudes about civic space actors (formal organizations and informal groups), as well as public discourse pertaining to democratic norms or rivals in the eyes of citizens.

Although Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine February 2022 undeniably altered the civic space landscape in Belarus and the E&E region for years to come, the historical information in this report is still useful in three respects. By taking the long view, this report sheds light on the Kremlin’s patient investment in hybrid tactics to foment unrest, co-opt narratives, demonize opponents, and cultivate sympathizers in target populations as a pretext or enabler for military action. Second, the comparative nature of these indicators lends itself to assessing similarities and differences in how the Kremlin operates across countries in the region. Third, by examining both domestic and external factors in tandem, this report provides a more holistic view of how to support resilient societies in the face of autocratizing forces at home and malign influence from abroad.

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

|

Civic Space Barometer |

Supporting Indicators |

|

Restrictions of civic space actors (January 2015–March 2021) |

|

|

Citizen attitudes toward civic space (2010–2021)

|

|

|

Russian projectized support relevant to civic space (January 2015–August 2021) |

|

|

Russian state media mentions of civic space actors (January 2015–March 2021) |

|

Notes: Table of indicators collected by AidData to assess the health of Belarus’s domestic civic space and vulnerability to Kremlin influence. Indicators are categorized by barometer (i.e., dimension of interest) and specify the time period covered by the data in the subsequent analysis.

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Belarus

A healthy civic space is one in which individuals and groups can assemble peacefully, express views and opinions, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. Laws, rules, and policies are critical to this space, in terms of rights on the books (de jure) and how these rights are safeguarded in practice (de facto). Informal norms and societal attitudes are also important, as countries with a deep cultural tradition that emphasizes civic participation can embolden civil society actors to operate even absent explicit legal protections. Finally, the ability of civil society actors to engage in activities without fear of retribution (e.g., loss of personal freedom, organizational position, and public status) or restriction (e.g ., constraints on their ability to organize, resource, and operate) is critical to the practical room they have to conduct their activities. If fear of retribution and the likelihood of restriction are high, this has a chilling effect on the motivation of citizens to form and participate in civic groups.

In this section, we assess the health of civic space in Belarus over time in two respects: the volume and nature of restrictions against civic space actors (section 2.1) and the degree to which Belarusians engage in a range of political and apolitical forms of civic life (section 2.2). Belarus accounted for the largest volume of restrictions initiated against civic space actors in the E&E region between January 2015 and March 2021, driven by high instances of both harassment or violence and state-backed legal cases. Against this backdrop, it is perhaps unsurprising why there is such a pronounced gap between Belarusians professed high degree of interest in politics juxtaposed with extremely low willingness to participate in common forms of civic life, political or otherwise. We delve into greater detail about these trends and other developments in Belarus’ domestic civic space in the remainder of this section.

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Belarus: Targets, Initiators, Trends Over Time

Belarusian civic space actors experienced 2,146 known restrictions between January 2015 and March 2021 (see Table 2). Thirty-one percent of restrictions were recorded in 2020, related to the presidential election, with the upsurge continuing into the first quarter of 2021 which alone accounted for 262 cases. [4] These restrictions were weighted toward state-backed legal cases (53 percent) and instances of harassment or violence (46 percent). There were fewer instances of newly proposed or implemented restrictive legislation (1 percent); however, these instances can have a multiplier effect in creating a legal mandate for a government to pursue other forms of restriction. These imperfect estimates are based upon publicly available information either reported by the targets of restrictions, documented by a third-party actor, or covered in the news (see Section 5). This data is best understood to be event-level data in that it records reported episodes of violence and harassment, as well as state-backed legal cases, as opposed to a count dataset that attempts to capture the universe of how many individuals were harassed. In this respect, these estimates substantially undercount the number of individuals affected. [5]

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of Belarusian Civic Space Actors

|

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021-Q1 |

Total |

||

|

Harassment/Violence |

98 |

106 |

138 |

98 |

62 |

364 |

120 |

986 |

||

|

Restrictive Legislation |

7 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

2 |

6 |

10 |

32 |

||

|

State-backed Legal Cases |

83 |

124 |

163 |

193 |

144 |

289 |

132 |

1128 |

||

|

Total |

188 |

232 |

301 |

296 |

208 |

659 |

262 |

2146 |

||

Notes: Table of the number of restrictions initiated against civic space actors in Belarus, disaggregated by type and year. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Belarus and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Belarus

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment/Violence

Restrictive Legislation

State-backed Legal Cases

Key Events Relevant to Civic Space in Belarus

|

March 2015 |

Russian President Putin calls for a single currency with the Kremlin's closest ex-Soviet allies, along with his Kazakh and Belarusian counterparts. |

|

|

August 2015 |

President Lukashenko pardons six jailed opposition leaders in a move widely seen as an attempt to persuade the EU to open up trade with Belarus. |

|

|

October 2015 |

President Lukashenko secures a fifth term. Belarusian independent media accuse the government of blocking websites pre-election. |

|

|

March 2016 |

The Ministry of Justice denies registration for the 6th time to the Belarusian Christian Democracy party due to “gross violations of law." |

|

|

September 2016 |

Only two opposition candidates win seats in parliamentary elections. Activists say the pair's success was engineered by the authorities. |

|

|

February 2017 |

Protests in Gomel call for Lukashenko's resignation over "social parasite tax" that targets the under-employed. |

|

|

April 2017 |

Leading opposition figure Mykalay Statkevich is jailed. A widespread wave of protests breaks out and another is called for on May 1st. |

|

|

November 2017 |

The EU pledges to deepen ties with 6 former Soviet states, including Belarus, as part of efforts to counter Russian influence. |

|

|

April 2018 |

Belarusian parliament prohibits unauthorized comments on online forums and requires online outlets to register as mass media. |

|

|

August 2018 |

After a scandal involving embezzlement of funds from the health service, Lukashenko dismisses Prime Minister Kabyakow and several ministers. |

|

|

Jan-Mar 2019 |

Washington and the Kremlin tussle for influence in Belarus, as it tries to negotiate oil prices with Russia and lifts a restriction on the number of U.S. diplomats allowed in its territory. |

|

|

November 2019 |

Opposition groups in Belarus lose their only two parliament seats and many activists are barred from running. |

|

|

January 2020 |

U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo says the U.S. is willing to provide Belarus with 100% of its oil and gas, taking aim at Russia which recently cut off supplies. |

|

|

April 2020 |

Hundreds of thousands of state employees take part in a government-decreed day of civic labor despite the country's rapid rise in COVID-19 cases. |

|

|

August 2020 |

Mass protests follow allegations of rigging after the political opposition is barred from presidential elections. The Prosecutor General's Office opens a criminal probe into the opposition’s attempts to” seize power.” Lukashenko claimed “foreign interference” and Russian President Putin promised him assistance upon request. |

|

|

October 2020 |

Lukashenko orders the partial closure of Belarus’s borders with Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Ukraine. He expels 35 diplomats from Poland and Lithuania after accusing NATO countries of meddling in internal affairs. |

|

|

February 2021 |

Russian President Vladimir Putin hosts his Belarusian counterpart for talks, amid reports suggesting that Lukashenko was going to Russia to secure another loan. |

|

Notes: The above charts visualize instances of civic space restrictions in Belarus, disaggregated by quarter and accompanied by a timeline of events in the political and civic space of Belarus. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Belarus and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

The Belarusian government was the most prolific initiator of restrictions of civic space actors, accounting for 938 recorded mentions. The police and other security forces were the most frequent channels of restrictions of civic space actors, though politicians and bureaucrats were also initiators of hostility including verbal attacks and threats (Figure 2). Domestic non-governmental actors were identified as initiators in 27 restrictions and there were many incidents involving unidentified assailants (31 mentions). By virtue of the way that the state-backed legal cases indicator was defined, the initiators are either explicitly government agencies and government officials or clearly associated with these actors (e.g., the spouse or immediate family member of a sitting official). Political opposition members were the most frequent targets of violence and harassment, appearing in 33 percent of all recorded instances (Figure 3).

There were five recorded instances of restrictions of civic space actors during this period involving the governments of Russia (four cases) and Ukraine (one case):

- In February 2016, Russian trolls targeted the Nasha Niva media portal amid their reporting on an entrepreneurs' strike. The tolls criticized the protestors and praised President Lukashenko as a great leader of all Slavs.

- Russian national and member of the Jehovah's Witnesses religious group, Nikolai Makhalichev, was detained in February 2020, spending 40 days in custody in Belarus after the Kremlin put him on an international wanted list. He was arrested for belonging to a banned religious community.

- Anton Rodnekov, Ivan Kravtsov and Maria Kolesnikova, leading members of Belarus’ political opposition (i.e., democratic forces), were seized by security forces in Minsk and forcibly taken to the Ukrainian border. The deportation, in September 2020, appears to have been in cooperation with the government of Ukraine, as Rodnekov and Kravtsov were arrested on the Ukrainian side.

- In October 2020, Russia placed Belarusian opposition leader, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, on its wanted list. The move was a blow to the protest movement in Belarus, which had denied having an anti-Russian agenda and sought Kremlin involvement in efforts to resolve the political crisis.

- In November 2020, the Kremlin placed Stepan Putilo and Roman Protasevich, founders of the Nexta Live opposition Telegram channel, on an international wanted list subsequent to the Belarusian government’s adding the individuals to a list of terrorists.

Figure 4 breaks down the targets of restrictions by political ideology or affiliation in the following categories: pro-democracy, pro-Western, and anti-Kremlin. [6] Pro-democracy organizations and activists were mentioned 1576 times as targets of restriction during this period. [7] Pro-Western organizations and activists were mentioned 811 times as targets of restrictions. [8] There were 349 instances where we identified the target organizations or individuals to be explicitly anti-Kremlin in their public views. [9] It should be noted that this classification does not imply that these groups were targeted because of their political ideology or affiliation, merely that they met certain predefined characteristics. In fact, these tags were deliberately defined narrowly such that they focus on only a limited set of attributes about the organizations and individuals in question.

Figure 2. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Belarus by Initiator

Number of Instances Recorded

Notes: The figure visualizes the number of recorded instances of restrictions of civic space actors in Belarus, categorized by the initiator. If an instance of violence or harassment targeted multiple groups, it is counted for each group. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Belarus and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Figure 3. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Belarus

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

Notes: This figure shows the number of instances of harassment/violence initiated against civic space actors in Belarus, disaggregated by the group targeted. If an instance of violence or harassment targeted multiple groups, it is counted for each group. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Belarus and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Figure 4. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Belarus by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment / Violence

Restrictive Legislation

State-Backed Legal Cases

Notes: These figures visualize instances of harassment/violence and restrictive legislation initiated against civic space actors in Belarus, categorized by whether targets were known to be “pro-democracy.” “pro-Western.” or “anti-Kremlin” as manually tagged by AidData staff. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

Instances of harassment (34 threatened, 861 acted upon) towards civic space actors were more common than episodes of outright physical harm (13 threatened, 78 acted upon) during the period. The majority of these restrictions (95 percent) were acted on, rather than merely threatened. However, since this data is collected on the basis of reported incidents, this likely understates threats which are less visible (see Figure 5). Of the 986 instances of harassment and violence, acted-on harassment accounted for the largest percentage (87 percent).

Figure 5. Threatened versus Acted-on Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Belarus

Number of Instances Recorded

Notes: This figure visualizes instances of harassment/violence against civic space actors in Belarus by type. For definitions, please refer to the associated methodology document. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Belarus and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Recorded instances of restrictive legislation (32) in Belarus are important to capture as they give government actors a mandate to constrain civic space with long-term cascading effects. This indicator is limited to a subset of parliamentary laws, chief executive decrees or other formal executive branch policies and rules that may have a deleterious effect on civic space actors, either subgroups or in general. Both proposed and passed restrictions qualify for inclusion, but we focus exclusively on new and negative developments in laws or rules affecting civic space actors. We exclude discussion of pre-existing laws and rules or those that constitute an improvement for civic space.

- The Belarusian government pursued numerous measures to curb independent media: expanding its power to block websites, remove content, restrict access to content it deemed to be “extremist,” as well as hamper the operations of foreign or partly foreign-owned media outlets.

- The regime also sought opportunities to hinder the activities of civic activists, formal non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and trade unions. It limited the ability of NGOs to secure foreign funding, selectively wielded a controversial “social parasite tax” to target individual human rights defenders and vocal opposition groups and required those organizing protests to agree to “hefty payments for policing services.” Moreover, the government ordered the unionizing of all enterprises under the leadership of the pro-government Federation of Trade Unions, increasing scrutiny and control of their activities.

- Nine new pieces of legislation were proposed or drafted in March 2021 alone, all aimed at criminalizing peaceful protests. The proposals ranged from increased scrutiny of lawyers who defended opposition activists to a bill to combat “the glorification of Nazism.” If passed, these laws would make it impossible to challenge the regime without inviting state-backed legal action.

Civic space actors were the targets of 1128 recorded instances of state-backed legal cases between January 2015 and March 2021. Individual activists and advocates were most frequently the defendants (Table 3). As shown in Figure 6, charges in these cases were often directly (96 percent) tied to fundamental freedoms (e.g., freedom of speech, assembly). There were some indirect charges (3 percent) such as drug trafficking or bribery, often used by regimes throughout the E&E region to discredit the reputations of civic space actors. There were 4 instances where the nature of the charge was coded as “unknown,” as there was insufficient information to make the determination.

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Belarus

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

|

Defendant Category |

Number of Cases |

|

Media/Journalist |

379 |

|

Political Opposition |

301 |

|

Formal CSO/NGO |

42 |

|

Individual Activist/Advocate |

382 |

|

Other Community Group |

54 |

|

Other |

18 |

Notes: This table shows the number of state-backed legal cases against civic space actors in Belarus, disaggregated by the targeted group. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Belarus and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Belarus

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

Notes: Bar chart of the number of state-backed legal cases brought against civic space actors in Belarus, disaggregated by the group targeted and the nature of the charge. If an instance of a state-backed legal case targeted multiple groups, it is counted for each group. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Belarus and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

2.2 Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Belarus

Belarusians’ interest in politics held relatively steady, hovering around 40 percent between 2011 and 2018—the two most recent waves of the World Values Survey. This interest in politics has not led to high levels of civic participation, however, and trends appear to be worsening. In 2018, Belarus had extremely low rates of participation in civic activities, and membership in all types of voluntary organizations declined since 2011. The one exception—high rates of membership in trade unions—is likely symptomatic of the legacy of Soviet trade unions and President Lukashenko's use of the Federation of Trade Unions in Belarus to sideline other political activity. Outside of the political arena, far fewer Belarusians donated to charities, helped strangers or volunteered with organizations in 2019 than 2010, according to the Gallup World Poll, plummeting to the bottom of the region.

In this section, we take a closer look at Belarusian citizens interest in politics, participation in political action or voluntary organizations, and confidence in institutions. We also examine how Belarusian involvement in less political forms of civic engagement—donating to charities, volunteering for organizations, helping strangers—has evolved over time.

2.2.1 Interest in Politics, Willingness to Act, and Membership in Voluntary Organizations

In 2011, 41 percent of Belarusians expressed an interest in politics, and by 2018 that share had grown slightly larger (+2 percentage points), according to the World Values Survey (Figure 7). Still, the majority remained disinterested in politics in both years. This muted interest was further reflected in extremely low rates of reported political action in Belarus (Figure 8). In 2018, only a small fraction of Belarusian survey respondents had joined a petition (10 percent), demonstration (7 percent), boycott (2 percent), or strike (2 percent). Although Belarusians reported relatively equal levels of interest in politics as their regional peers, they were comparatively less likely to have engaged in these common forms of civic activities (by -2 to 10 percentage points). The slight preference for petitions and demonstrations over boycotts and strikes is in line with citizens’ preferences across the E&E region as a whole.

Figure 7. Interest in Politics: Belarusian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2018

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of Belarusian respondents that were interested or not interested in politics in 2011 and 2018, as compared to the regional average. Sources: World Values Survey Wave 6 (2011) and the Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey Wave 2017-2021.

Figure 8. Political Action: Belarusian Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2018

Percentage of Respondents

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of Belarusian respondents who reported past participation in each of four types of political action—petition, boycott demonstration, and strike—as well as their future willingness to do so. This information was not available for Belarusian respondents in 2011. Sources: Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey Wave 2017-2021.

Figure 9. Political Action: Participation by Belarusian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2018

Percentage of Respondents Reporting “Have Done”

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of Belarusian respondents who reported past participation in each of four types of political action in 2018, as compared to the regional average. This information was not available for Belarusian respondents in 2011. Sources: Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey Wave 2017-2021.

It is reasonable to assume that low levels of political participation are symptomatic of the Lukashenko regime’s track record of restrictions of civic space actors (see Section 2.1), which likely has had a chilling effect on Belarusians’ willingness to engage in public displays of collective action or expression. However, this dynamic does not appear limited to the political arena alone, as the majority of Belarusians were also not members of voluntary organizations, either political or nonpolitical. [10] Belarusian membership in voluntary organizations consistently trailed the region, on average. While only one dimension of civic engagement, membership in voluntary organizations [11] is a useful barometer of the willingness of citizens to join with one another outside of work, government, or familial networks.

In both 2011 and 2018, fewer than 10 percent of Belarusians said they were members of most types of organizations—from churches and sports teams to environmental organizations and political parties—lagging behind their regional peers (Table 4). Belarusian respondents were also less likely to be members of political parties than citizens in other E&E countries: a gap that held relatively steady between 2011 (-6 percentage points) and 2018 (-4 percentage points). Restrictions imposed by President Lukashenko on the registration and operation of non-governmental organizations likely serve as barriers to civic participation (see Section 2.1). [12]

Labor and trade unions were the notable exception to this general rule (Figure 10). Over 40 percent of Belarusian respondents to the World Values Survey in 2011 and 2018 said they were members of a trade union. This comparatively high rate of membership is likely driven by the long-standing Federation of Trade Unions in Belarus, a Soviet era institution that claims approximately 97 percent of working Belarusians as members. [13] Ostensibly, Lukashenko’s co-optation of the Federation of Trade Unions in Belarus, which serves as a government-operated NGO (GONGO), could undercut other forms of civic participation. The regime installed party loyalists at the helm of the Federation, inhibiting the ability of anti-Lukashenko factions to politically organize, and sidelining the growth of independent trade unions. [14]

In a departure from low levels of political activity and organization membership, Belarusian citizens’ had confidence in their country’s institutions on par with their regional peers. [15] In 2011, 56 percent of Belarusians said they were confident in their country’s institutions, on average. Belarusian citizens gave their highest high marks to the military (75 percent) and churches (73 percent), consistent with a number of countries across the E&E region. Interestingly, despite their extremely high rates of membership in labor unions, Belarusian respondents had lower levels of confidence in them (44 percent), perhaps reflective of their known co-optation by the government. however, as political parties and the press had lower rates of confidence (35 percent and 39 percent, respectively).

Belarusian trust in institutions overall declined by an average of 7 percentage points in 2018, though this was driven by a large drop in confidence in the nation’s civil service—from 65 percent of respondents in 65 to 31 percent in 2018 (Table 5). It is unclear if there was a single incident that sparked this massive decline in trust, or more general frustration with the government’s lack of transparency, independent bodies to investigate official corruption, and closed graft trials. The civil service remains a weak spot in Belarus, even as it faces pressure from President Lukashenko, who has forced officials to resign after supporting opposition figures. [16]

Table 4. Belarusian Citizens’ Membership in Voluntary Organizations by Type, 2011 and 2018

|

Voluntary Organization |

Membership, 2011 |

Membership, 2018 |

Percentage Point Change |

|

Church or Religious Organization |

11% |

8% |

-3.2 |

|

Sport or Recreational Organization |

9% |

4% |

-4.8 |

|

Art, Music, or Educational Organization |

6% |

4% |

-2.7 |

|

Labor Union |

44% |

40% |

-4.6 |

|

Political Party |

2% |

2% |

-0.3 |

|

Environmental Organization |

1% |

1% |

-0.1 |

|

Professional Association |

5% |

3% |

-2.2 |

|

Humanitarian or Charitable Organization |

3% |

2% |

-0.6 |

|

Consumer Organization |

1% |

0% |

-0.9 |

|

Self-Help Group, Mutual Aid Group |

1% |

1% |

+0.5 |

|

Other Organization |

5% |

3% |

-1.1 |

Notes: This table shows the percentage of Belarusian respondents that reported membership in various categories of voluntary organizations in 2011 and 2018. Sources: World Values Survey Wave 6 (2011) and the Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey Wave 2017-2021.

Figure 10. Voluntary Organization Membership: Belarusian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2018

Percentage of Respondents Reporting Membership

Notes: This graph highlights membership in a selection of key organization types for Belarus. “Other community group” is the mean of responses for the following responses: "Art, music or educational organization,” “Church or religious organization,” “Sport or recreational organization,” "Environmental organization,” "Professional association,” "Humanitarian or charitable organization,” "Consumer organization,” "Self-help group, mutual aid group,” "Other organization.” Sources: World Values Survey Wave 6 (2011) and the Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey Wave 2017-2021.

Table 5. Belarusian Confidence in Key Institutions, 2011 and 2018

|

Institution |

Confidence, 2011 |

Confidence, 2018 |

Percentage Point Change |

|

Church or Religious Organization |

73% |

58% |

-14.5 |

|

Military |

75% |

64% |

-10.7 |

|

Press |

39% |

37% |

-1.6 |

|

Labor Unions |

44% |

49% |

+5.1 |

|

Police |

55% |

59% |

+4.9 |

|

Courts |

55% |

57% |

+2.2 |

|

Government |

56% |

50% |

-6.1 |

|

Political Parties |

35% |

26% |

-9.3 |

|

Parliament |

49% |

46% |

-3.4 |

|

Civil Service |

65% |

31% |

-34.5 |

|

Environmental Organizations |

66% |

54% |

-11.3 |

Notes: This table shows the percentage of Belarusian respondents that reported confidence in various categories of institutions in 2011 and 2018. Sources: World Values Survey Wave 6 (2011) and the Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey Wave 2017-2021.

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

The Gallup World Poll’s (GWP) Civic Engagement Index affords an additional perspective on Belarusian citizens’ attitudes towards less political forms of participation between 2010 and 2019. This index measures the proportion of citizens that reported giving money to charity, volunteering at organizations, and helping a stranger on a scale of 0 to 100. [17] Belarus began the period slightly ahead of its E&E regional peers (+4 percentage points), with civic engagement scores of 29 and 25 in 2010, respectively. However, its performance on the index subsequently began a sharp descent beginning in 2013 through 2019, the last year of available data. [18] By 2019, Belarus had dropped to the bottom of the region’s rankings with a civic engagement score of 16 points (-13 percentage points from 2010).

Declines in Belarusians' willingness to engage in activities such as volunteering and helping strangers contributed to the country’s weakening civic participation scores. At its peak performance, in 2010, 36 percent of Belarusians reported helping a stranger and 35 percent had volunteered with an organization. By 2019, the average Belarusians’ appetite to engage in these apolitical forms of civic participation had tapered off, as only 24 percent of those surveyed said they had helped a stranger that year, while a mere 8 percent had volunteered. Comparatively, Belarusians’ level of charitable contributions held relatively steady with only a minor decline (-2 percentage points) from 16 percent in 2010 to 14 percent in 2019.

Unlike what we have observed elsewhere in the E&E region, Belarus’ index scores do not appear to correlate with the country’s economic performance. [19] Instead, Belarusians’ decreasing involvement in apolitical channels of civic life is more likely reflective of the increasingly restrictive environment for expression and collective action under Lukashenko’s ongoing rule.

One final note is that these trends may have reversed following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. While Gallup has not conducted its World Poll in Belarus in 2020 or 2021, there was an uptick in citizen engagement elsewhere in the region and around the world as citizens rallied in response to COVID-19, even in the face of lockdowns and limitations on public gatherings. When facing the unique stresses of disease, lockdowns, and economic turbulence, citizens reported increasing their commitment to their community, rather than holding onto their strained resources. That said, we cannot say for certain that these broader regional trends bore out in Belarus due to limited data.

Figure 11. Civic Engagement Index: Belarus versus Regional Peers

Notes: This graph shows how scores for Belarusian citizens varied on the Gallup World Poll Index of Civic Participation between 2010 and 2019, as compared to the regional mean of E&E countries. Sources: Gallup World Poll, 2010-2019. While the poll was conducted in other countries in 2020 and 2021, data was not available for Belarus in these two years.

3. External Channels of Influence: Kremlin Civic Space Projects and Russian State-Run Media in Belarus

Foreign governments can wield civilian tools of influence such as money, in-kind support, and state-run media in various ways that disrupt societies far beyond their borders. They may work with the local authorities who design and enforce the prevailing rules of the game that determine the degree to which citizens can organize themselves, give voice to their concerns, and take collective action. Alternatively, they may appeal to popular opinion by promoting narratives that cultivate sympathizers, vilify opponents, or otherwise foment societal unrest. In this section, we analyze data on Kremlin financing and in-kind support to civic space actors or regulators in Belarus (section 3.1), as well as Russian state media mentions related to civic space, including specific actors and broader rhetoric about democratic norms and rivals (section 3.2).

The Kremlin supported 21 Belarusian civic organizations via 30 civic space-relevant projects between January 2015 to August 2021. Somewhat of a departure from its modus operandi in other countries in the region, the Kremlin focused its activities in Belarus on promoting Russian-Belarusian integration and promoting the framework of the Union State, [20] as opposed to its emphasis elsewhere on cultural programming with minority groups of ethnic Russians.

Belarus was a popular target audience for Russian state media, which captured 12 percent of the Kremlin’s media mentions across the region, lagging only Ukraine. The preponderance of this coverage coincided with the 2020 presidential elections and anti-government protests in Belarus, continuing into early 2021, as the Kremlin grew concerned of a potential color revolution and losing a staunch pro-Russia ally in President Lukashenko.

We delve into greater detail about these channels of Kremlin influence in Belarus’ civic space in the remainder of this section.

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to Belarusian Civic Space

Moscow prefers to directly engage and build relationships with individual civic actors in Belarus, as opposed to investing in broader based institutional development which accounted for a mere 13 percent (4 projects) of its overtures. The Russian government’s interest in cultivating these relationships with Belarusian civic actors appears to be fairly durable, with a slight uptick from 2019 to 2020, despite partial data and disruptions due to COVID-19 (Figure 12). The lack of identified projects in 2021 is likely due to the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns and the partial data for that year.

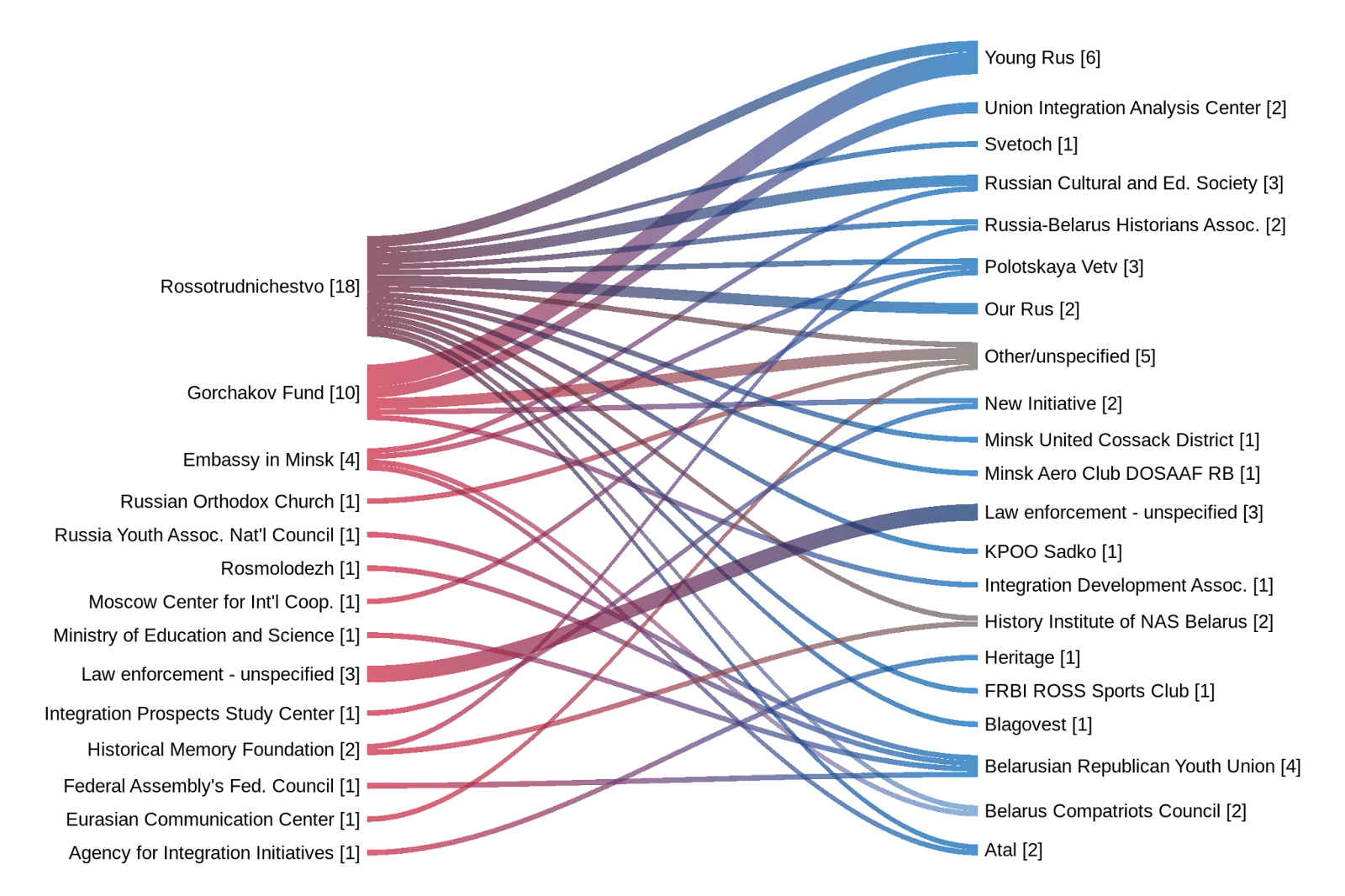

The Kremlin routed its engagement in Belarus through 14 different channels (Figure 13), including government ministries, federal centers, language and culture-focused funds, the Eurasian Communication Center, the Moscow Center for International Cooperation, and the Russian embassy in Minsk. The stated missions of these Russian government entities emphasize themes such as education and culture promotion, patriotic training for civic space leaders, and security-related issues. Many entities couch their activities in the language of Eurasian integration, to a greater extent than that seen in other E&E countries.

However, not all of these Russian state organs were equally important. The Gorchakov Fund [21] and Rossotrudnichestvo [22] supplied over four-fifths of all known Kremlin-backed support (15 organizations via 25 projects) to civic space actors and regulators in Belarus. Indeed, many of the other Russian organizations identified as directing support to civic space actors undertook their activities in conjunction with either the Gorchakov Fund or Rossotrudnichestvo. The Gorchakov Fund, accounting for 37 percent of projects between 2015 and 2020, promotes Russian culture and provides support to non-governmental organizations to bolster Russia’s image abroad. Rossotrudnichestvo—an autonomous agency under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with a mandate to promote political and economic cooperation abroad—is associated with 53 percent of the Kremlin’s overtures to Belarusian civic actors.

Figure 12. Russian Projects Supporting Belarusian Civic Space Actors by Type

Number of Projects Recorded, January 2015–August 2021

Notes: This figure shows the number of projects directed by the Russian government to either civic society actors or government regulators of this civic space between January 2015 and August 2021. No new activities were identified in 2021. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Figure 13. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Belarusian Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

Notes: This figure shows which Kremlin-affiliated agencies (left-hand side) were involved in directing financial or in-kind support to which civil society actors or regulators (right-hand side) between January 2015 and August 2021. Lines are weighted to represent counts of projects. The total weight of lines may exceed the total number of projects, due to many projects involving multiple donors and/or recipients. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

3.1.1 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Belarusian Civic Space

Civil society organizations (CSOs) were the most common beneficiaries in 77 percent of identified Russian-backed projects in Belarus. Other recipients of the Kremlin’s attention included a forum training leading bloggers in Belarus and the Belarusian police force.

Nearly all of the Belarusian recipient organizations work in the education and culture sector (19 organizations), most often with an emphasis on promoting shared Russian-Belarusian history or facilitating educational forums and patriotic training. In contrast to its efforts in other countries, the Kremlin’s collaborations with civic actors on religious or social issues were relatively more limited in Belarus and when they did occur, were typically wrapped into educational or cultural events. Rossotrudnichestvo’s support to the religious organization Blagovest to host a children’s art exhibition as part of the competition “Beauty of God’s World,” is one such example.

As in other countries, many Belarusian beneficiaries of Kremlin support were organizations with an explicit emphasis on working with youth (11 organizations, 58 percent of identified organizations). The Russian Orthodox Church has similarly targeted youth in its support of military-patriotic boot camps for Belarusian children. These activities are aligned with the goals of the Suvorov military schools, in particular the training of future military and civic leaders, albeit with far looser institutional structures.

Rossotrudnichestvo also supported two groups promoting distinct ethnic and cultural identities: the public association for the Chuvash population Atal and the Minsk United Cossack District. This second group, which promotes Cossack and Russian culture, is notable as Cossack groups have been used by the Kremlin as paramilitary units in Donbas and Crimea, as well as police and anti-protest political enforcers within Russia. [23]

Many Belarusian recipient organizations were comparatively newer than those Russia engages with in other countries. Of those with a known founding date, [24] nine (56 percent) were founded after 2010. This may reflect the difficulties for CSOs to register and be recognized by the Belarusian government, but it is also noteworthy that the profile of the newer organizations diverges from those founded in the earlier 2000s.

Integration was a unifying theme among the newer organizations: the association “Promoting the Development of Integration, International Social, Cultural and Business Cooperation,” (founded in 2018); the Center for Research on Union Integration Issues “New Initiative,” (founded in 2019); and the Center for Analysis and Forecasting of Union Integration Processes (founded in 2020). [25] Presenting themselves as modern think tanks, these organizations are a stark contrast with longer-standing organizations such as the cultural and educational association (KPOO) Sadko that also received Kremlin support. Founded in 2010, Sadko aims to preserve Russian culture and promote Belarusian-Russian friendship and hosts holiday celebrations, historical discussions, and film nights.

The Kremlin also partnered with the Belarusian police on several occasions on projects relevant to civic space: training provided in September 2018 in preparation for the European Games, a commitment for a reserve unit of Russian law enforcers to intervene in August 2020 amid protests against Lukashenko’s government, and a September 2020 joint training exercise in the Brest region to “combat terrorism.” [26] Given the importance of southern Belarus as a staging ground for the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, it is plausible in hindsight that these joint exercises could have served dual purposes of both influencing civic space within Belarus, as well as helping Moscow lay important logistical groundwork for its subsequent military hostilities against the authorities in Kyiv.

Geographically, Russian-state overtures were oriented towards Minsk, or organizations based in the Belarusian capital, which received 67 percent of all projects (Figure 13). Mahilyow, Belarus’s third largest city, also captured a fair amount of attention from Moscow (13 percent of projects). Gomel, Belarus’s second largest city and just over 20 miles from the Russian border in the country’s southeastern corner, received two projects, both of which involved hosting the International Forum of the Leaders of the NGOs of the Union State at the Russian Center for Science and Culture. The lack of activity in Belarus’s eastern cities may be simply a result of their smaller and less ethnically Russian populations, but it may also indicate a Russian focus on building support in the regions closest to its own border.

Figure 14. Locations of Russian Support to Belarusian Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

Notes: This map visualizes the geographic distribution of Kremlin-backed support to civic space actors in Belarus. Three projects are unmapped because their geographic focus is unspecified. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

3.1.2 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Belarusian Civic Space

As seen elsewhere in the E&E region, the primary mode of Russian support in Belarus appears to not be direct transfers of funding but rather non-financial “support.” Only two of the projects we identified described recipients receiving grants, both of which were awarded by the Gorchakov Fund. Instead, the Russian government relies much more extensively on supplying various forms of non-financial “support,” such as training, technical assistance, and other in-kind contributions to its Belarusian partners.

The Kremlin places outsized emphasis on event support to Belarusian civic actors since 2015, referenced in 22 projects. Russian institutions co-sponsor activities with a Belarusian CSO, school or compatriot union to undertake a particular event, frequently focused on promoting Russian values, supporting youth politics, and developing networks between pro-Russian associations. The Kremlin’s “support” is typically in the form of space, materials, or other logistical and technical contributions to Belarusian partners.

Supporting youth-focused programming is a common strategy for the Kremlin in Belarus. The Kremlin’s relationship to two Belarusian CSOs—the Belarusian Republican Youth Union and the socio-cultural association Young Rus—is illustrative of this approach. In 2016, the National Council of Youth and Children's Associations of Russia and the Belarusian Republican Youth Union partnered to host the Russian-Belarusian Youth Forum in Minsk. Intended to promote Russian history and cooperation between the two countries, the youth forum received logistics support from three Kremlin-affiliated organs: the Federation Council of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation, the Ministry of Education and Science, and the Federal Agency for Youth Affairs (Rosmolodezh). Similarly, Young Rus hosted the International Forum of the Leaders of NGOs of the Union State in 2017, 2018, and 2020 with support from the Gorchakov Fund and Rossotrudnichestvo. [27]

The emphasis of the aforementioned Young Rus forum series on mobilizing youth to support greater integration of the Union State is also part of a broader theme in the Kremlin’s programing in Belarus. Sixty-four percent of the Kremlin-affiliated organizations (9 of 14 actors) supporting civic space-relevant projects in Belarus sponsored at least one activity that directly referenced the Russian-Belarusian Union State and broader integration language as a core theme. There was even an identified instance of a Belarusian NGO, supported by Russia, promoting Eurasian integration abroad at a political summer camp for Moldovan youth in August 2016.

In a noticeable point of departure from its go-to playbook elsewhere in the region, the Kremlin backed relatively few activities with local Russian compatriot unions. [28] There are likely three reasons for this break from standard practice. First, Russian’s status as the predominant language in Belarus may eliminate the need to promote informal communities of local Russian speakers. Second, the Kremlin may view promoting the framework of the Russian-Belarusian Union State as better advancing its influence objectives than pursuing soft power via its compatriot policy. Third, a smaller proportion of ethnic Russians in Belarus consider themselves a minority than in other countries in the region. [29]

A final insight from the Kremlin’s engagement with civic actors in Belarus is that Russian activities appear to build on one another, signaling deepening engagement over time. For example, Rossotrudnichestvo’s commitment to open a Russian Center for Science and Culture in Mahilyow in 2018 was built upon the foundation of a pre-existing relationship it established with the Mahilyow-based Russian Cultural and Educational Society to co-host a “festival” in October 2017: “We Live in Friendship with Neighbors.”

3.2 Russian Media Mentions Related to Civic Space Actors and Democratic Rhetoric

Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced Belarusian civic actors 1,547 times from January 2015 to March 2021. Three-quarters of these mentions (1,165 instances) were of domestic actors, while the remaining quarter (515 instances) focused on foreign and intergovernmental actors operating in Belarus’ civic space. To understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of Belarusian citizens, we also analyzed 1,194 mentions of five keywords in conjunction with Belarus: North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO, the United States, the European Union, democracy, and the West.

3.2.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Belarusian Civic Space Actors

Roughly one-quarter (27 percent, 317 instances) of Russian media mentions pertaining to domestic actors in Belarusian civic space referred to specific groups by name. The named domestic actors represent a diverse cross-section of organizational types, ranging from political parties to CSOs to media outlets. However, formal civil society organizations are the most frequently named organization type, accounting for 57 percent (182 mentions) of named domestic actors in Belarus. The large number of formal CSO mentions is driven by three organizations: the Coordination Council (65 mentions), the Viasna Human Rights Center (39 mentions), [30] and the Tell the Truth Movement (Govori Pravdu) (28 mentions). Domestic media were also prominent, capturing 30 percent of mentions (94 instances). The Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) was most frequently mentioned in this group, accounting for 36 mentions alone. [31]

Russian state media mentions of specific Belarusian civic space actors were most often neutral (81 percent) in tone. The remaining coverage was mostly negative (16 percent), with only 10 mentions (3 percent) receiving positive coverage. The Coordination Council took the brunt of the negative sentiment (35 of the total 50 negative mentions of named domestic groups). Created by the main Belarusian opposition candidate in the 2020 election, Svetlana Tsikhanouskaya, to facilitate a democratic transition of power, the Coordination Council remained the driving organizer of the Belarusian protests against President Alexander Lukashenko following allegations of election fraud. Interestingly, there is a discernible shift in the tone of Russian media coverage of the Coordination Council from initially positive at the start of the protests in mid-August 2020 to decidedly negative beginning in September 2020.

Voices of the political opposition (i.e., democratic forces) were also more likely to attract negative coverage including the Belarus Christian Democracy Party and Belarusian Democratic Movement (4 negative mentions), Belarusian Left Party (1 negative mention), Belarusian National Front Party (2 negative mentions), and the Nexta Live opposition Telegram channel (2 negative mentions). Other named domestic organizations attracting negative coverage included the Viasna Human Rights Center (3 negative mentions), BelTA (2 negative mentions), and the Zubr Youth Movement (1 negative mention). Conversely, pro-Lukashenko voices such as the Belarusian Orthodox Church (1 positive mention), BelaPAN (1 positive mention), and the Communist Party of Belarus (1 positive mention) were more likely to receive favorable attention in accordance with the Kremlin’s consistent support of its staunchly pro-Russian ally in Belarus.

Aside from these named organizations, TASS and Sputnik made 848 more generalized references to domestic Belarusian non-governmental organizations, protesters, opposition activists, or other informal groups during the same period. Although the preponderance of this coverage was still neutral (58 percent), it was noticeably more negative (34 percent) than that typically accorded to organizations by name with only 64 positive mentions.

When looking at the domestic civic space actors as a whole, the top mentioned groups center around the 2020 Belarusian protests following a fraudulent presidential election (Table 6). At the outset of the unrest, the Russian government did not take a strong stance and appeared to put pressure on the incumbent leader Alexander Lukashenko, evidenced by more neutral or positive coverage of opposition or anti-regime groups. However, following the continued protests, Russian state-owned media sentiment towards these organizations radically shifted to portraying Belarusian protesters, opposition groups, and anti-Lukashenko political parties in a negative light.

Moscow’s extensive coverage of these protests reflects the Kremlin’s concerns regarding the prospect of new “color revolutions” in countries close to its border. Negative coverage accorded to opposition voices and civic space actors viewed as anti-Lukashenko underscores the Kremlin’s use of its state-run media to discredit domestic civic space actors and maintain the status quo.

Table 6. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in Belarus by Sentiment

|

Domestic Civic Group |

Extremely Negative |

Somewhat Negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat Positive |

Extremely Positive |

Grand Total |

|

Opposition |

7 |

92 |

127 |

4 |

0 |

230 |

|

Protesters |

9 |

54 |

121 |

23 |

1 |

208 |

|

Protest |

1 |

32 |

39 |

1 |

0 |

73 |

|

Coordination Council |

2 |

33 |

28 |

2 |

0 |

65 |

|

Viasna Human Rights Center |

0 |

3 |

36 |

0 |

0 |

39 |

|

Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) |

0 |

0 |

35 |

0 |

1 |

36 |

Notes: This table shows the breakdown of the domestic civic space actors most frequently mentioned by the Russian state media (TASS and Sputnik) between January 2015 to March 2021 and the tone of that coverage by individual mention. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

3.2.2 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in Belarusian Civic Space

While the majority of Russian state media mentions covered domestic organizations, TASS and Sputnik mentioned by name 72 foreign organizations (382 mentions), 22 intergovernmental organizations (133 mentions), and 26 general foreign actors (66 mentions). The majority of external actors were mentioned in connection to coverage of the 2020 presidential election and subsequent protests. As a case in point, the top-five most frequently mentioned external actors were in relation to international election observer missions (Figure 7), and Dozhd TV is an independent Russian media outlet that covered the Belarusian elections.

Russian state media mentions of external actors in Belarus’ civic space, both named and unnamed, was predominantly neutral (79 percent) in tone. The remaining coverage was largely negative (17 percent), with Western-affiliated intergovernmental actors, such as the EU and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, bearing the brunt of negative sentiment. Russian state media typically employed two narratives—that the Western intergovernmental organizations should have been more involved in monitoring the 2020 presidential elections in Belarus and that Western organizations, such as the National Endowment for Democracy, acted as puppeteers for the protests following the election and facilitated grassroots mobilization in Belarus. This negative coverage is consistent with the Russian media’s attitude towards any Western institutions and entities that did not recognize the legitimacy of Lukashenko’s election.

Table 7. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Belarus by Sentiment

|

External Civic Group |

Extremely Negative |

Somewhat Negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat Positive |

Grand Total |

|

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) / Including Minsk and ODIHR |

5 |

6 |

28 |

4 |

43 |

|

European Union / Including European Commission, Parliament, Council of Europe |

9 |

4 |

15 |

1 |

29 |

|

Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) |

0 |

0 |

19 |

1 |

20 |

|

Dozhd TV (TV Rain) |

0 |

3 |

16 |

0 |

19 |

|

International Election Observers |

0 |

0 |

15 |

0 |

15 |

Notes: This table shows the breakdown of the external civic space actors most frequently mentioned by the Russian state media (TASS and Sputnik) in relation to Belarus between January 2015 to March 2021 and the tone of that coverage by individual mention. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

3.2.3 Russian State Media’s Focus on Belarus’s Civic Space over Time

The preponderance of media mentions (72 percent) related to Belarusian civic space occurred in just one year: 2020 (1,115 mentions). However, similar to what we observed in section 2 with restrictions of civic space actors, the uptick in Russian state media coverage continued into the first quarter of 2021 (the end of our reporting period) with an additional 191 mentions in those three months alone. Although there were minor spikes in Russian state-run media coverage in October 2015 for the Belarusian presidential elections and in February and March 2017 for the “March of the Angry Belarusians” protests, the coverage of the 2020 presidential election and subsequent protests was at a scale that dwarfed previous mentions (Figure 15).

The 2020 presidential election attracted substantial international media attention in response to growing reports of police violence and human rights abuses towards anti-government protesters. As previously mentioned, Russian state media coverage of the elections was largely neutral in tone; however, coverage became increasingly negative the longer the protests drew on and as the Kremlin grew concerned of the prospects of another color revolution on its border and the potential launch of an ally in Lukashenko. These findings are not dissimilar to comparable coverage by Russian state media of elections and related protest movements in Moldova and Armenia.

Figure 15. Russian State Media Mentions of Belarusian Civic Space Actors

Number of Mentions Recorded

Notes: This figure shows the distribution and concentration of Russian state media mentions of Belarusian civic space actors between January 2015 and March 2021. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

3.2.4 Russian State Media Coverage of Western Institutions and Democratic Norms

In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of Belarusian citizens, we analyzed the frequency and sentiment of coverage related to five keywords in conjunction with Belarus. [32] Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News referenced all five keywords from January 2015 to March 2021 (Table 8). Russian state media mentioned the “West” (326 instances), the European Union (300 instances), the United States (273 instances), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (254 instances), and democracy (41 instances) with reference to Belarus during this period. Fifty-one percent of these references were negative in tone, with the remainder of the coverage largely neutral (42 percent). Consistent with what we observed with civic actor mentions in sections, there was a dramatic uptick in Russia state media mentions of terms related to democratic norms and rivals during and immediately following the 2020 presidential election in Belarus (Figure 16).

Table 8. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

|

Keyword |

Extremely Negative |

Somewhat Negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat Positive |

Extremely Positive |

Grand Total |

|

West |

66 |

158 |

86 |

16 |

0 |

326 |

|

European Union |

17 |

95 |

153 |

35 |

0 |

300 |

|

United States |

33 |

89 |

127 |

23 |

1 |

273 |

|

NATO |

26 |

112 |

110 |

6 |

0 |

254 |

|

Democracy |

2 |

11 |

24 |

4 |

0 |

41 |

Notes: This table shows the frequency and tone of mentions by Russian state media (TASS and Sputnik) related to five key words—NATO, the European Union, the United States, democracy, and the West—between January 2015 and March 2021 in articles related to Belarus. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Figure 16. Keyword Mentions by Russian State Media in Relation to Belarus

Number of Unique Keyword Instances of NATO, the U.S., the EU, Democracy, and the West in Russian State Media

Notes: This figure shows the distribution and concentration of Russian state media mentions of five keywords in relation to Belarus between January 2015 and March 2021. Sources: Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Of these terms, Russian state media mentioned the West the most frequently (326 instances) and the majority of this coverage was negative (69 percent) or neutral (26 percent). Russian state media used its coverage to fan the flame of disapproval for the West’s purported meddling in the 2020 presidential elections in Belarus and accusing Western organizations of instigating the resulting protests. For example, one article about the protests argued that “...the West had launched preparations for protests long before the elections.” [33] Additional topics where the West was mentioned negatively include the Russian annexation of Crimea, perceived NATO expansion, and sanctions against Russia.

The next most frequently mentioned terms were the European Union (300 instances), closely followed by the United States (273 instances). The majority of these mentions were in relation to the Minsk accords and general cooperation between the EU, the U.S., and Russia. Coverage was most often neutral in the case of 51 percent of mentions for the EU and 47 percent for the U.S. Nevertheless, both actors attracted a sizable share of negative coverage, most often in cases where Russian media sought to portray the EU (37 percent negative mentions) and U.S. (45 percent negative mentions) as less attractive partners for Belarus than Russia.