Armenia: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence

Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, Lincoln Zaleski

April 2023

[Skip to Table of Contents] [Skip to Chapter 1]Executive Summary

This report surfaces insights about the health of Armenia’s civic space and vulnerability to malign foreign influence in the lead up to Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Research included extensive original data collection to track Russian state-backed financing and in-kind assistance to civil society groups and regulators, media coverage targeting foreign publics, and indicators to assess domestic attitudes to civic participation and restrictions of civic space actors. Crucially, this report underscores that the Kremlin’s influence operations were not limited to Ukraine alone and illustrates its use of civilian tools in Armenia to co-opt support and deter resistance to its regional ambitions. A companion profile on Nagorno-Karabakh—the longest-running conflict in post-Soviet Eurasia according to the Crisis Group (2023)—provides information on civic space and Kremlin influence in the occupied territory. [1]

The analysis was part of a broader three-year initiative by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to produce quantifiable indicators to monitor civic space resilience in the face of Kremlin influence operations over time (from 2010 to 2021) and across 17 countries and 7 occupied or autonomous territories in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). Below we summarize the top-line findings from our indicators on the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Armenia, as well as channels of Russian malign influence operations:

- Restrictions of Civic Actors: Armenian civic space actors were the targets of 241 restrictions between January 2015 and March 2021, including harassment or violence (80 percent), state-backed legal cases (14 percent), and restrictive legislation (6 percent). Thirty-two percent of cases were recorded in 2016 alone, coinciding with anti-government protests following the seizure of Erebuni police station on July 17 by Sasna Tsrer, an armed militant group with links to the non-violent opposition movement Founding Parliament. Political opposition members were most frequently targeted, and the Armenian government was the primary initiator. The Russian and Azerbaijani governments were involved in five and three of the instances of restrictions of civic space actors, respectively.

- Attitudes Towards Civic Participation: Armenians reported growing interest in politics (+10 percentage points) between 2011 and 2018. There was also a greater openness to the possibility of political participation in the form of petitions, boycotts, demonstrations or strikes. Outside of politics, Armenia lags farther behind other E&E countries. Few Armenians are members of voluntary organizations, and distrust in institutions is high. Although Armenia charted its strongest performance on Gallup’s Civic Engagement Index in 2021—buoyed by 61 percent of Armenians helping a stranger—its rates of charitable donations and volunteerism still trail regional peers.

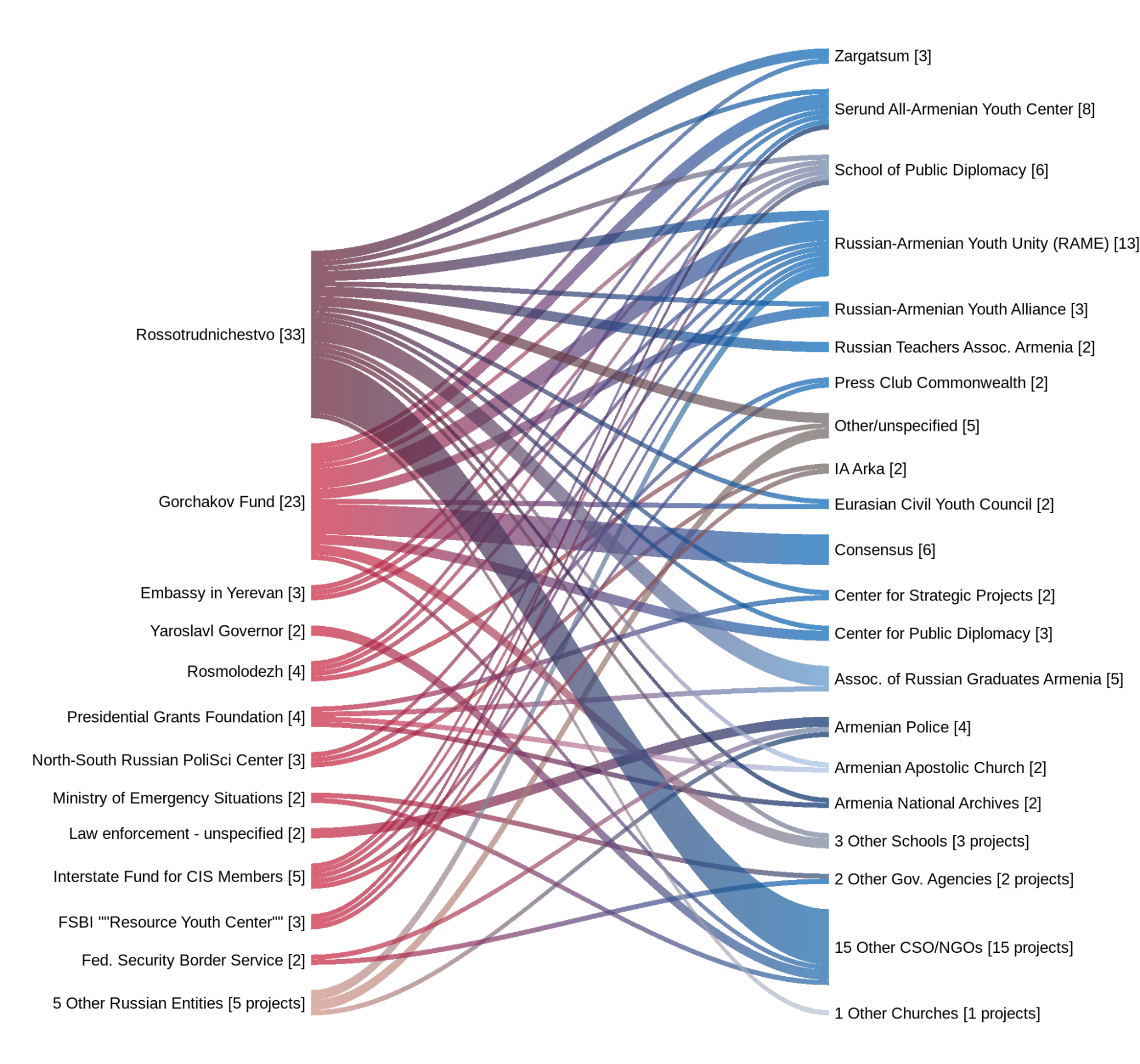

- Russian-backed Civic Space Projects: The Kremlin supported 38 Armenian civic organizations via 49 civic space-relevant projects between January 2015 to August 2021. The Russian government routed its engagement in Armenia through 17 different state channels; however, the Gorchakov Fund and Rossotrudnichestvo alone supplied over three-quarters of all identified projects. Over half of the Armenian recipient organizations worked in the education and culture sector—some emphasizing Russian language and culture, while others facilitated youth vocational training or patriotic education.

- Russian State-run Media: Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News referenced Armenian civic actors 286 times from January 2015 to March 2021. Three-quarters of these mentions were of domestic actors, most commonly political parties and informal political movements, with the remainder including references to intergovernmental and foreign organizations. Oblique references to unnamed foreign actors—“foreign NGOs,” “Western NGOs,” “Western media,” and “the West”—tended to attract the most negative coverage among Russian state media, which sought to discredit domestic pro-Western or pro-democracy voices by casting them as beholden to the U.S. or EU.

Table of Contents

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Armenia

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Armenia: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time.

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

2.2 Attitudes Toward Civic Space in Armenia

2.2.1 Interest in Politics and Willingness to Act as Barometers of Armenian Civic Space

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to Armenia’s Civic Space

3.1.1 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Armenia’s Civic Space

3.1.2 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Armenia's Civic Space

3.2 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

3.2.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Armenian Civic Space Actors

3.2.2 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in Armenian Civic Space

3.2.3 Russian State Media’s Focus on Armenia’s Civic Space over Time

3.2.4 Russian State Media Coverage of Western Institutions and Democratic Norms

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

5.3 Russian Projectized Support to Civic Space Actors or Regulators

5.4 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

Figures and Tables

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of Armenian Civic Space Actors

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Armenia

Figure 2. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Armenia

Figure 3. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Armenia by Initiator

Figure 4. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Armenia by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Figure 5. Threatened versus Acted-on Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Armenia

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Armenia

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Armenia

Figure 7. Interest in Politics: Armenian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2018

Figure 8. Political Action: Armenian Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2011 versus 2018

Figure 9. Political Action: Participation by Armenian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2018

Figure 10. Voluntary Organization Membership: Armenian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2018

Table 4. Armenian Citizens’ Membership in Voluntary Organizations by Type, 2011 and 2018

Table 5. Armenian Confidence in Key Institutions versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2018

Figure 11. Civic Engagement Index: Armenia versus Regional Peers

Figure 12. Russian Projects Supporting Armenian Civic Space Actors by Type

Figure 13. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Armenian Civic Space

Figure 14. Locations of Russian Support to Armenian Civic Space

Table 6. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in Armenia by Sentiment

Table 7. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Armenia by Sentiment

Figure 15. Russian State Media Mentions of Armenian Civic Space Actors

Table 8. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

Figure 16. Keyword Mentions by Russian State Media in Relation to Armenia

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, and Lincoln Zaleski. John Custer, Sariah Harmer, Parker Kim, and Sarina Patterson contributed editing, formatting, and supporting visuals. Kelsey Marshall and our research assistants provided invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report including: Jacob Barth, Kevin Bloodworth, Callie Booth, Catherine Brady, Temujin Bullock, Lucy Clement, Jeffrey Crittenden, Emma Freiling, Cassidy Grayson, Annabelle Guberman, Sariah Harmer, Hayley Hubbard, Hanna Kendrick, Kate Kliment, Deborah Kornblut, Aleksander Kuzmenchuk, Amelia Larson, Mallory Milestone, Alyssa Nekritz, Megan O’Connor, Tarra Olfat, Olivia Olson, Caroline Prout, Hannah Ray, Georgiana Reece, Patrick Schroeder, Samuel Specht, Andrew Tanner, Brianna Vetter, Kathryn Webb, Katrine Westgaard, Emma Williams, and Rachel Zaslavsk. The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

This research was made possible with funding from USAID's Europe & Eurasia (E&E) Bureau via a USAID/DDI/ITR Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) cooperative agreement (AID-A-12-00096). The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

A Note on Vocabulary

The authors recognize the challenge of writing about contexts with ongoing hot and/or frozen conflicts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consistently label groups of people and places for the sake of data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that terminology is political, but our use of terms should not be construed to mean support for one faction over another. For example, when we talk about an occupied territory, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the government in the capital. Or, when we analyze the de facto authorities’ use of legislation or the courts to restrict civic action, it is not to grant legitimacy to the laws or courts of separatists, but rather to glean meaningful insights about the ways in which institutions are co-opted or employed to constrain civic freedoms.

Citation

Custer, S., Mathew, D., Burgess, B., Dumont, E., Zaleski, L. (2023). Armenia: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence. April 2023. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William and Mary.

1. Introduction

How strong or weak is the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Armenia? To what extent do we see Russia attempting to shape civic space attitudes and constraints in Armenia to advance its broader regional ambitions? Over the last three years, AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—has collected and analyzed vast amounts of historical data on civic space and Russian influence across 17 countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). [2] In this country report, we present top-line findings specific to Armenia from a novel dataset which monitors four barometers of civic space in the E&E region from 2010 to 2021 (Table 1). [3]

For the purpose of this project, we define civic space as: the formal laws, informal norms, and societal attitudes which enable individuals and organizations to assemble peacefully, express their views, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. [4] Here we provide only a brief introduction to the indicators monitored in this and other country reports. However, a more extensive methodology document is available via aiddata.org which includes greater detail about how we conceptualized civic space and operationalized the collection of indicators by country and year.

Civic space is a dynamic rather than static concept. The ability of individuals and organizations to assemble, speak, and act is vulnerable to changes in the formal laws, informal norms, and broader societal attitudes that can facilitate an opening or closing of the practical space in which they have to maneuver. To assess the enabling environment for Armenian civic space, we examined two indicators: restrictions of civic space actors (section 2.1) and citizen attitudes towards civic space (section 2.2). Because the health of civic space is not strictly a function of domestic dynamics alone, we also examined two channels by which the Kremlin could exert external influence to dilute democratic norms or otherwise skew civic space throughout the E&E region. These channels are Russian state-backed financing and in-kind support to government regulators or pro-Kremlin civic space actors (section 3.1) and Russian state-run media mentions related to civic space actors or democracy (section 3.2).

Since restrictions can take various forms, we focus here on three common channels which can effectively deter or penalize civic participation: (i) harassment or violence initiated by state or non-state actors; (ii) the proposal or passage of restrictive legislation or executive branch policies; and (iii) state-backed legal cases brought against civic actors. Citizen attitudes towards political and apolitical forms of participation provide another important barometer of the practical room that people feel they have to engage in collective action related to common causes and interests or express views publicly. In this research, we monitored responses to citizen surveys related to: (i) interest in politics; (ii) past participation and future openness to political action (e.g., petitions, boycotts, strikes, protests); (iii) trust or confidence in public institutions; (iv) membership in voluntary organizations; and (v) past participation in less political forms of civic action (e.g., donating, volunteering, helping strangers).

In this project, we also tracked financing and in-kind support from Kremlin-affiliated agencies to: (i) build the capacity of those that regulate the activities of civic space actors (e.g., government entities at national or local levels, as well as in occupied or autonomous territories ); and (ii) co-opt the activities of civil society actors within E&E countries in ways that seek to promote or legitimize Russian policies abroad. Since E&E countries are exposed to a high concentration of Russian state-run media, we analyzed how the Kremlin may use its coverage to influence public attitudes about civic space actors (formal organizations and informal groups), as well as public discourse pertaining to democratic norms or rivals in the eyes of citizens.

Although Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine February 2022 undeniably altered the civic space landscape in Armenia and the broader E&E region for years to come, the historical information in this report is still useful in three respects. By taking the long view, this report sheds light on the Kremlin’s patient investment in hybrid tactics to foment unrest, cºo-opt narratives, demonize opponents, and cultivate sympathizers in target populations as a pretext or enabler for military action. Second, the comparative nature of these indicators lends itself to assessing similarities and differences in how the Kremlin operates across countries in the region. Third, by examining domestic and external factors in tandem, this report provides a holistic view of how to support resilient societies in the face of autocratizing forces at home and malign influence from abroad.

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

|

Civic Space Barometer |

Supporting Indicators |

|

Restrictions of civic space actors (January 2015–March 2021) |

|

|

Citizen attitudes toward civic space (2010–2021)

|

|

|

Russian projectized support relevant to civic space (January 2015–August 2021) |

|

|

Russian state media mentions of civic space actors (January 2015–March 2021) |

|

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Armenia

A healthy civic space is one in which individuals and groups can assemble peacefully, express views and opinions, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. Laws, rules, and policies are critical to this space, in terms of rights on the books (de jure) and how these rights are safeguarded in practice (de facto). Informal norms and societal attitudes are also important, as countries with a deep cultural tradition that emphasizes civic participation can embolden civil society actors to operate even absent explicit legal protections. Finally, the ability of civil society actors to engage in activities without fear of retribution (e.g., loss of personal freedom, organizational position, and public status) or restriction (e.g ., constraints on their ability to organize, resource, and operate) is critical to the practical room they have to conduct their activities. If fear of retribution and the likelihood of restriction are high, this has a chilling effect on the motivation of citizens to form and participate in civic groups.

In this section, we assess the health of civic space in Armenia over time in two respects: the volume and nature of restrictions against civic space actors (section 2.1) and the degree to which Armenians engage in a range of political and apolitical forms of civic life (section 2.2)

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Armenia: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time.

Armenian civic space actors experienced 241 known restrictions between January 2015 and March 2021 (see Table 2). These restrictions were weighted toward instances of harassment or violence (80 percent). There were fewer instances of state-backed legal cases (14 percent) and newly proposed or implemented restrictive legislation (6 percent); however, these instances can have a multiplier effect in creating a legal mandate for a government to pursue other forms of restriction. These imperfect estimates are based upon publicly available information either reported by the targets of restrictions, documented by a third-party actor, or covered in the news (see Section 5). [5]

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of Armenian Civic Space Actors

|

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021-Q1 |

Total |

|

|

Harassment/Violence |

38 |

64 |

14 |

25 |

20 |

26 |

6 |

193 |

|

|

Restrictive Legislation |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

15 |

|

|

State-backed Legal Cases |

5 |

12 |

8 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

33 |

|

|

Total |

45 |

77 |

24 |

30 |

25 |

33 |

6 |

241 |

|

Instances of restrictions of Armenian civic space actors were unevenly distributed across this time period and peaked in 2016 (Figure 1). Thirty-two percent of cases were recorded in 2016 alone, coinciding with anti-government protests following the seizure of Erebuni police station on July 17 by Sasna Tsrer, an armed militant group of disenfranchised veterans of the Nagorno-Karabakh war with links to the non-violent opposition movement Founding Parliament. [6] The protests were not necessarily in support of the militia members, but rather an expression of widespread disenchantment with the regime. Members of the political opposition were the most frequent targets of violence and harassment (33 percent of instances), followed by journalists and other members of the media (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Armenia

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment/Violence

Restrictive Legislation

State-backed Legal Cases

Key Events Relevant to Civic Space in Armenia

|

January 2015 |

Gyumri massacre - Russian soldier kills 7 members of the Avetisyan family, leading to riots outside the Russian embassy |

|

|

June 2015 |

Start of the #ElectricYerevan protests in the summer of 2015 against a massive hike in electricity rates in Armenia |

|

|

December 2015 |

Passage of a constitutional referendum viewed as a bid for President Serzh Sargsyan to stay in power after a second term alongside mass protests |

|

|

April 2016 |

Increase of fighting along the Nagorno-Karabakh border leads to over 300 casualties |

|

|

July 2016 |

An armed opposition group took over Erebuni police station in Yerevan provoking mass anti-government protests calling for a peaceful resolution to the crisis |

|

|

April 2017 |

Parliamentary elections were held amidst mass protests, government crackdowns, alleged voting irregularities, and concerns of a Russian hacking and disinformation campaign |

|

|

October 2017 |

Presidents of Armenia and Azerbaijan negotiate in Geneva in attempts to settle Nagorno-Karabakh border dispute |

|

|

March 2018 |

Mass protests erupt with the election of Armen Sarkissian by the National Assembly rather than a popular vote and the subsequent nomination of Serzh Sargsyan as Prime Minister. |

|

|

May 2018 |

Nikol Pashinyan is elected Prime Minister following his prominent role in the Velvet Revolution |

|

|

December 2018 |

Pashinyan calls a snap election which removes the Republican Party from government |

|

|

April 2019 |

A coordinated online influence operation (#SutNikol) seeks to mobilize anti-Pashinyan sentiment and VETO movement activists seek the closure of the Open Society Foundation |

|

|

December 2019 |

The government approves a draft law on non-governmental organizations requires substantial public disclosures on their financing, activities, and staffing |

|

|

March 2020 |

Civil society representatives express concern over regulations which imposed fines on media and social media users for publishing stories on COVID-19 that do not use official sources |

|

|

August 2020 |

Police and environmental activists clashed in a series of protests related to the controversial Amulsar gold mine operated by Lydian Armenia |

|

|

September 2020 |

New violence erupts between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Nagorno-Karabakh region. |

|

Figure 2. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Armenia

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2017 – March 2021

The Armenian government was the most prolific initiator of restrictions of civic space actors, accounting for 129 recorded mentions (Figure 3). Domestic non-governmental actors were identified as Initiators in 29 restrictions and there were some incidents involving unidentified assailants (31 mentions). By virtue of the way that the state-backed legal cases indicator was defined, the Initiators are either explicitly government agencies and government officials or clearly associated with these actors (e.g., the spouse or immediate family member of a sitting official).

Figure 3. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Armenia by Initiator

Number of Instances Recorded

There were eight recorded instances of restrictions of Armenian civic space actors during this period involving a foreign government:

- Five restrictions involved the Russian government or Kremlin-affiliated organizations. Three incidents featured Kremlin-affiliated actors engaging in verbal harassment targeting pro-European NGOs for “trying to set public sentiments in Armenia against Russia” or making money from “U.S. desires for coup d’états in other countries.” The other two recorded incidents involved non-verbal forms of harassment such as the 2015 hacking of EVN reporter Maria Titizian by Fancy Bear, a Kremlin-affiliated group, for her coverage of the #ElectricYerevan protests and the 2019 detention and deportation of Armenian political expert, Stepan Grigoryan, viewed as retaliation for his collaboration with European NGOs and pro-democracy foundations.

- Azerbaijan was involved in three instances of harassment. In September 2020, two journalists from "Le Monde" and two from " 24News " were injured, while reporting in Martuni region, in eastern Nagorno Karabakh. The journalists claimed the injuries came as a result of attacks coordinated by Azerbaijani authorities. On their part, Azerbaijani officials said that the attacks against the media were supported by the Armenian side. Similar to the Russian interference, in November 2020, a representative of the Azerbaijani government accused NGOs in Armenia of financing terrorism with the support of the Armenian diaspora. In February 2021, Azerbaijani media, likely in collusion with the Azerbaijani government, orchestrated a smear campaign and attack against the Armenian human rights defender of Armenia, Arman Tatoyan.

Figure 4 breaks down the targets of restrictions by political ideology or affiliation in the following categories: pro-democracy, pro-Western, and anti-Kremlin. [7] Pro-democracy organizations and activists were mentioned 79 times as targets of restriction during this period. [8] Pro-Western organizations and activists were mentioned 36 times as targets of restrictions. [9] There were 29 instances where we identified the target organizations or individuals to be explicitly anti-Kremlin in their public views. [10] It should be noted that this classification does not imply that these groups were targeted because of their political ideology or affiliation, merely that they met certain predefined characteristics. In fact, these tags were deliberately defined narrowly such that they focus on only a limited set of attributes about the organizations and individuals in question.

Figure 4. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Armenia by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment/Violence

State-backed Legal Cases

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

Instances of harassment (8 threatened, 119 acted upon) towards civic space actors were more common than episodes of outright physical harm (7 threatened, 59 acted upon) during the period. The vast majority of these restrictions (92 percent) were acted on, rather than merely threatened. However, since this data is collected on the basis of reported incidents, this likely understates threats which are less visible (see Figure 5). Of the 193 instances of harassment and violence, acted-on harassment accounted for the largest percentage (62 percent).

Figure 5. Threatened versus Acted-on Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Armenia

Number of Instances Recorded

Recorded instances of restrictive legislation (15) in Armenia are important to capture as they give government actors a mandate to constrain civic space with long-term cascading effects. This indicator is limited to a subset of parliamentary laws, chief executive decrees or other formal executive branch policies and rules that may have a deleterious effect on civic space actors, either subgroups or in general. Both proposed and passed restrictions qualify for inclusion, but we focus exclusively on new and negative developments in laws or rules affecting civic space actors. We exclude discussion of pre-existing laws and rules or those that constitute an improvement for civic space.

The Armenian government used legislation to curb and sanction actors in the civic space. A few illustrative examples include:

- Amendments to Armenia’s Freedom of Information Law, in April 2020, allowed the Ministry of Environment to refuse to disclose information (e.g., the breeding sites of rare species), if it was deemed to have a negative impact on the environment. This legislation limited the ability of journalists to hold authorities accountable.

- In 2015, the Armenian government proposed and passed a constitutional amendment allowing restrictions of the expression and practice of religion in order to protect state security. In 2017, the Ministry of Justice sponsored a draft bill to amend the Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations to discriminate against some denominations.

- In 2016, a new law on television and radio took effect that limited each region in Armenia to one television station and caused at least 10 television stations to close, sparking concerns that this would negatively affect public discourse.

- The government proposed new changes, in 2017, to a law on NGOs requiring them to re-register and change their names to meet arbitrary requirements.

- In 2018 and 2019, there were a series of restrictions that promised to curb access to information and criticism of the government. Specifically, in 2018, the Yerevan City Council and the Armenian parliament voted to restrict journalists’ access to meetings.

Civic space actors were the targets of 33 recorded instances of state-backed legal cases between January 2015 and March 2021, with the highest volume in 2016. Journalists and other members of the media were most frequently the defendants (Table 3), often in connection with their investigative reporting on connections between businesses and the government. As shown in Figure 6, charges in these cases were most often directly (85 percent) tied to fundamental freedoms (e.g., freedom of speech, assembly). There were some indirect charges (15 percent) such as bribery, corruption and possession of weapons, often used by regimes throughout the E&E region to discredit the reputations of civic space actors.

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Armenia

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

|

Defendant Category |

Number of Cases |

|

Media/Journalist |

14 |

|

Political Opposition |

13 |

|

Formal CSO/NGO |

3 |

|

Individual Activist/Advocate |

3 |

|

Other Community Group |

0 |

|

Other |

0 |

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Armenia

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2015–March 2021

2.2 Attitudes Toward Civic Space in Armenia

Armenians reported growing interest in politics (+10 percentage points) between 2011 [11] and 2018—the two most recent waves of the World Values Survey—and there was a greater openness to the possibility of political participation in the form of petitions, boycotts, demonstrations or strikes. The Armenian public’s greater interest in politics is all the more notable in the face of a comparative decline in such sentiment across the region in the same time period.

Outside of politics, Armenia lags farther behind other E&E countries, on average. Few Armenians are members of voluntary organizations, except for political parties. Even as Armenia charted its strongest performance on the Gallup World Poll’s Civic Engagement Index in 2021—buoyed by 61 percent of Armenians reportedly helping a stranger that year—its rates of charitable donations and volunteerism still trail regional peers. It is possible that Armenians’ limited appetite for less political forms of civic engagement may reflect Armenians’ higher levels of distrust in institutions relative to other E&E countries (-6 percentage points on average).

In this section, we take a closer look at Armenian citizens’ interest in politics, participation in political action or voluntary organizations, and confidence in institutions. We also examine how Armenian involvement in less political forms of civic engagement—donating to charities, volunteering for organizations, helping strangers—has evolved over time.

2.2.1 Interest in Politics and Willingness to Act as Barometers of Armenian Civic Space

In 2011, a mere 35 percent of Armenians expressed interest in politics, compared to 42 percent of survey respondents across the region (Figure 7). Consistent with this relative disinterest, fewer than 10 percent of Armenians reported that they had participated in petitions, boycotts, demonstrations or strikes (Figure 8). Nor were they willing to consider doing so in future: over three-quarters of Armenian respondents said they were unlikely to sign a petition (74 percent), participate in a boycott (88 percent), join a demonstration (77 percent) or participate in a strike (85 percent) in future. Comparing different forms of political participation, Armenians were somewhat more likely to express willingness to join petitions or demonstrations, 19 and 14 percent respectively, in future than other activities.

By 2018, Armenians reported more favorable attitudes towards political participation. Forty-five percent of Armenian respondents said they were interested in politics (+10 percentage points), in contrast with a marked decline elsewhere in the region (-6 percentage points). Armenians also translated this interest in politics into action as they reported higher levels of participation across four types of civic activities One-fifth of respondents said they had joined a petition (+14 percentage points). Relatively fewer Armenians participated in demonstrations, strikes, and boycotts than in petitions, [12] but involvement in these activities was also up by 2 to 6 percentage points when compared with 2011.

Armenians also evidenced a more positive outlook towards the possibility of engaging in political activities, even if they had not done so to date. Approximately a quarter of Armenian respondents said that they might sign a petition, join a strike, or participate in a boycott in future. [13] Strikingly, over one-third of Armenians indicated that they might be willing to join in a future demonstration—a 22 percentage point increase—which may reflect greater optimism about bottom-up pressure ushering in reforms or less fear of government reprisals. This openness to joining demonstrations likely benefited from heavily publicized and prolonged public protests in the lead up to 2018 that engaged actors across the political spectrum and mainstreamed this as a familiar channel of civic participation.

It should be noted that these survey results likely understate the gains in Armenian attitudes towards political participation in recent years. The fieldwork for the most recent wave of the World Values Survey was conducted between February and April 2018, following substantial opposition gains in the 2017 parliamentary elections but prior to the major political shifts in the latter part of 2018 with the ascendance of Nikol Pashinyan as Prime Minister and toppling of the regime of President Serzh Sargsyan.

Figure 7. Interest in Politics: Armenian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2018

Figure 8. Political Action: Armenian Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2011 versus 2018

Figure 9. Political Action: Participation by Armenian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2018

Percentage of Respondents Reporting “Have Done”

Only 3 percent of Armenian respondents were members of voluntary organizations in 2011, less than half as likely as their regional peers (Table 4). The one exception to this general rule were political parties: at 10 percent, Armenian membership in these institutions exceeded the regional average by 3 percentage points (Figure 10). Unlike Azerbaijan, Armenians’ high membership rates in political parties appeared to reflect genuine political competition, as the 2012 parliamentary elections were tightly contested. [14] Comparatively, environmental and consumer groups were the least popular avenues for civic engagement, counting just one percent of Armenian respondents among their membership.

Consistent with lower levels of political activity and membership in voluntary organizations, Armenian citizens’ trust in institutions was also well below average in 2011 (Table 5). Only 39 percent of Armenian respondents to the 2011 WVS said they were confident in their country’s institutions, on average, trailing their regional peers by 15 percentage points. Military and religious organizations each enjoyed the confidence of more than 80 percent of Armenians, but there were much lower levels of trust in political parties (22 percent), despite high levels of membership, and labor unions (13 percent).

In line with their rosier outlook toward political action, Armenian membership in voluntary organizations also marginally improved in 2018, by an average of 1.3 percent. In 2018, art, music, and educational organizations overtook political parties as the most popular type of organization in Armenia, counting 9 percent of Armenian respondents among their members, versus 6 percent for political parties. Political parties were the only organizations that saw a drop in reported membership (-4 percentage points since 2011), shifting from leading to falling behind the regional average.

Overall, Armenian trust in institutions remained the same on average in 2018, though this obscures some shifting preferences. The military and religious institutions experienced a drop-off in favorability compared to 2011; however, they still enjoyed the confidence of the vast majority of Armenians, 82 and 70 percent, respectively. In an encouraging sign for Armenia’s civic space, confidence in the press and in labor unions improved by 11 percent each between 2011 and 2018. Despite these improvements, Armenian confidence in institutions still trailed their regional peers by 6 percentage points, on average.

Figure 10. Voluntary Organization Membership: Armenian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2018

Table 4. Armenian Citizens’ Membership in Voluntary Organizations by Type, 2011 and 2018

|

Voluntary Organization |

Membership, 2011 |

Membership, 2018 |

Percentage Point Change |

|

Church or Religious Organization |

3% |

5% |

+2.3 |

|

Sport or Recreational Organization |

3% |

6% |

+3.3 |

|

Art, Music or Educational Organization |

2% |

9% |

+6.1 |

|

Labor Union |

2% |

2% |

+0.3 |

|

Political Party |

10% |

6% |

-4.2 |

|

Environmental Organization |

1% |

3% |

+1.9 |

|

Professional Association |

2% |

4% |

+2.0 |

|

Humanitarian or Charitable Organization |

1% |

4% |

+2.9 |

|

Consumer Organization |

1% |

1% |

+0.2 |

|

Self-Help Group, Mutual Aid Group |

1% |

1% |

+0.4 |

|

Other Organization |

1% |

1% |

-0.9 |

Table 5. Armenian Confidence in Key Institutions versus Regional Peers, 2011 and 2018

|

Institution |

Confidence, 2011 |

Confidence, 2018 |

Percentage Point Change |

|

Church or Religious Organization |

80% |

70% |

-9.8 |

|

Military |

88% |

82% |

-6.0 |

|

Press |

28% |

38% |

+10.8 |

|

Labor Unions |

13% |

24% |

+11.1 |

|

Police |

38% |

39% |

+1.1 |

|

Courts |

30% |

35% |

+5.4 |

|

Government |

38% |

24% |

-13.9 |

|

Political Parties |

22% |

25% |

+2.2 |

|

Parliament |

26% |

26% |

+0.2 |

|

Civil Service |

33% |

31% |

-2.2 |

|

Environmental Organizations |

37% |

37% |

+0.9 |

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

The Gallup World Poll’s (GWP) Civic Engagement Index affords an additional perspective on Armenian citizens’ attitudes towards less political forms of participation between 2010 and 2021. This index measures the proportion of citizens that reported giving money to charity, volunteering at organizations, and helping a stranger on a scale of 0 to 100. [15] Although Armenia’s civic engagement scores consistently trailed the regional mean (by an average of 7 points), its performance on the index has improved in recent years, steadily gaining ground from a low of 19 points in 2014 [16] to a high of 29 points by 2021 (Figure 11).

Armenia’s relatively stronger performance on the index in 2021 was buoyed by the 61 percent of respondents who reportedly helped a stranger that year, close on the heels of the regional average of 63 percent. The share of Armenians who donated to charity and volunteered also improved compared to the 2019 (data is unavailable for 2020); however, Armenia still trailed other E&E countries on these measures by larger margins (-22 and -6 percentage points, respectively). This upward trend is consistent with improving civic engagement across the region and around the world as citizens rallied in response to COVID-19, even in the face of lockdowns and limitations on public gatherings. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen as to whether this initial improvement will be sustained in future.

Unlike many other Europe & Eurasia region countries, Armenia’s overall civic engagement scores do not appear to correlate with the performance of the country’s economy; however, rates of charitable giving by Armenians were positively and moderately correlated with GDP. [17] This suggests that Armenians feel more secure giving to charities when they have more economic security, though these rates are still quite low, and do not drive the overall index.

Figure 11. Civic Engagement Index: Armenia versus Regional Peers

3. External Channels of Influence: Kremlin Civic Space Projects and Russian State-Run Media in Armenia

Foreign governments can wield civilian tools of influence such as money, in-kind support, and state-run media in various ways that disrupt societies far beyond their borders. They may work with the local authorities who design and enforce the prevailing rules of the game that determine the degree to which citizens can organize themselves, give voice to their concerns, and take collective action. Alternatively, they may appeal to popular opinion by promoting narratives that cultivate sympathizers, vilify opponents, or otherwise foment societal unrest. In this section, we analyze data on Kremlin financing and in-kind support to civic space actors or regulators in Armenia (section 3.1), as well as Russian state media mentions related to civic space, including specific actors and broader rhetoric about democratic norms and rivals (section 3.2).

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to Armenia’s Civic Space

The Kremlin supported 38 known Armenian civic organizations and 49 civic space-relevant projects in Armenia during the period of January 2015 to August 2021. The composition of these activities indicates that Moscow prefers to directly engage and build relationships with individual civic actors, as opposed to investing in broader based institutional development which accounted for a mere 10 percent (5 projects) of its overtures. The Russian government’s interest in cultivating these relationships with Armenian civic actors appears to be fairly durable, as the number of identified project activities remained steady for much of the period (Figure 12). The sharp drop off after 2019 was likely attributable to disruptions due to COVID-19 in 2020 and partial data for 2021 (through August).

Figure 12. Russian Projects Supporting Armenian Civic Space Actors by Type

Number of Projects Recorded, January 2015–August 2021

The Kremlin routed its engagement in Armenia through 17 different state channels (Figure 13), including numerous government ministries, federal centers, language and culture-focused funds, the border guard of the security services, the administration of Yaroslavl Oblast (a local government entity), and the Russian embassy in Yerevan. The stated missions of these Russian government entities tend to emphasize themes such as youth development, public diplomacy, education and culture promotion, and security related issues. Economic development and civil society development were more often supporting themes than the primary purpose of all but three of these entities.

However, not all of these Russian state organs were equally important. The Gorchakov Fund [18] and Rossotrudnichestvo supplied over three-quarters of all known Kremlin-backed support (30 organizations, 39 projects). Indeed, many of the other Russian organizations identified as directing support to civic space actors in this time period undertook their activities in conjunction with either the Gorchakov Fund or Rossotrudnichestvo. The Gorchakov Fund, which accounted for over one-third of all Russian state-backed civic space projects identified between 2015 and 2021 (37 percent), aims to promote Russian culture abroad and provides projectized support to non-governmental organizations to bolster Russia’s image abroad. Rossotrudnichestvo—an autonomous agency under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with a mandate to promote political and economic cooperation abroad—is associated with nearly half (49 percent) of the Kremlin’s overtures to Armenian civic actors.

Figure 13. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Armenian Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

3.1.1 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Armenia’s Civic Space

Civil society organizations (CSOs) are not the only type of civic space actor in Armenia, but they were the most common beneficiaries of Russian state-backed overtures, accounting for 73 percent of identified projects. Other non-governmental recipients of the Kremlin’s attention included compatriot unions of Russian diaspora living in Armenia, [19] schools, and churches. The Armenian security services, namely the police and armed forces, received the lion’s share of Russia’s civic space-related efforts focused on the government. However, the Kremlin also supported projects with the Russian-Armenian Center of Emergency Response as well as the National Archives.

Over half of the Armenian recipient organizations worked in the education and culture sector (22 organizations), many with an emphasis on Russian language and culture promotion while others facilitate vocational training or patriotic education. This included one organization receiving Kremlin support in 2021, the Vanadzor-based Friends of Russia NGO. Rossotrudnichestvo partnered with the NGO to co-host a virtual event celebrating the birth of Russian poet Osip Mandelstam. The Kremlin also engaged with civic actors working on a broader set of issues related to social, religious, humanitarian, media, politics, and security concerns. Notably, a substantial number of the beneficiaries of Kremlin support were organizations that had an explicit emphasis on working with Armenian youth (15 organizations).

Geographically, Russian-state overtures were oriented towards Yerevan or at least organizations based in the Armenian capital, which received 57 percent of all projects (see Figure 14). Gyumri, Armenia’s second largest city and home to Russia’s 102nd military base, also captured a fair amount of attention from Moscow (16 percent of projects). The Kremlin’s overtures to civic actors in Gyumri may have been calculated, at least in part, to alleviate tensions that have arisen among Armenians protesting the controversial base and a string of civilian deaths at the hands of Russian military officers engaging in violence with impunity.

Figure 14. Locations of Russian Support to Armenian Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

3.1.2 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Armenia's Civic Space

Moscow’s engagement with Armenian civic space actors is extremely opaque; however, what little we have been able to glean from examining its project-specific activities is that the Kremlin typically does not directly transfer money to its beneficiaries. In fact, only four of the Russian state-backed projects identified between 2015 and 2021 were explicitly coded as providing “funding” to an Armenian counterpart institution. Instead, the Russian government relies more extensively on supplying various forms of non-financial “support” such as training, technical assistance, and other in-kind contributions to its Armenian partners.

The Kremlin has placed an outsized emphasis on two forms of support to individual Armenian civic actors since 2015—event support and political skills training for youth, referenced in 33 and 9 projects, respectively. Both of these approaches involve Russian institutions co-sponsoring activities with an Armenian CSO, school or compatriot union to undertake a particular event, frequently focused on promoting Russian values, supporting youth politics, and creating youth unions. [20] The nature of the Kremlin’s “support” is typically in the form of space, materials, or other logistical and technical contributions to Armenian partners via its various organs.

Russian-Armenian Youth Unity (RAME), the single largest known recipient of Russia’s overtures to civic actors with eight projects, is one such example. In the first half of 2019, the Gorchakov Foundation announced that RAME, which identifies its mission as the “patriotic education of young people and the preservation of historical memory,” received a grant to promote the “development of civic consciousness: the experience of the states of the Eurasian space.”

This strategy of targeting CSOs working explicitly with Armenian youth to promote Russian civic values is not unique to the Kremlin’s partnership with RAME. In fact, two of the next largest recipients of Russian state-backed civic space-related projects were Consensus, which supports model Collective Security Treaty Organization conferences (similar to model United Nations) for young people, and the Association of Students of Russian Universities in Armenia (which promotes linkages between Armenian and Russian educational and cultural institutions). These two youth-focused CSOs received six and four Russian-state backed projects, respectively. This strategy of youth engagement appears to be a consistent modus operandi for how the Kremlin seeks to influence civic values in other countries in the region, except for Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, where constrictions in broader channels of CSO engagement require Russian state actors to work almost exclusively with the older population or to focus on involvement in institutional development.

Although the preponderance of its focus appeared to be oriented towards promoting Russian civic values via sympathetic non-governmental interlocutors, the Kremlin also routed support to Armenian government entities that could create a more hostile environment for civic space. We identified five known instances of Russian state-backed support to the Armenian security services that could use that increased capacity to restrict civic space actors. Significantly, all of these overtures pre-dated the 2018 rise of Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, with no further instances documented since. It could be that with the rise of a former journalist and political leader widely seen as pro-Western, Moscow may have shifted more of its emphasis towards working with more sympathetic non-governmental allies.

The Kremlin’s pre-2018 support to the security services typically took the form of joint training and scholarships to study in Russia for Armenia’s civilian police or military officers. One such example was a joint training exercise conducted between Russian Federal Security Service Border Service units and Armenia’s Armed Forces and police near the Russian military base in Gyumri. These training sessions are similar to joint exercises occurring along Azerbaijan’s border and in Moldova’s autonomous regions, though in Armenia may also be a function of the country’s broader military agreements with Russia.

Of course, Moscow’s engagement with Armenia’s security services was not limited to joint exercises and training. Notably, another form of lateral learning occurred in November 2016, when an unspecified Russian law enforcement agency reportedly worked with the Armenian police to create a portrait database of criminals modeled on one used in Russia. Although it is hard to know at a distance how this database was ultimately deployed, this could have been a potent tool in facilitating then Prime Minister Serzh Sargysan’s subsequent crackdown on anti-government protests in 2017 and early 2018.

3.2 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced Armenian civic actors 286 times from January 2015 to March 2021. Approximately 76 percent of these mentions (216 instances) were of domestic actors, while the remaining quarter (70 instances) focused on foreign and intergovernmental actors operating in Armenia’s civic space. Russian state media covered a variety of civic actors, mentioning 74 organizations by name and 17 informal groups. In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of Armenian citizens, we also analyzed 181 mentions of five keywords in conjunction with Armenia: North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO, the United States, the European Union, democracy, and the West. In this section, we examine Russian state media coverage of domestic and external civic space actors, how this has evolved over time, and the portrayal of democratic institutions and Western powers to Armenian audiences.

3.2.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Armenian Civic Space Actors

Over half (58 percent) of the Russian media mentions pertaining to domestic actors in Armenia’s civic space referred to specific groups by name. These groups represent a diverse cross-section of organizational types—from political parties and media outlets to civil society organizations and grassroots community movements. Formal political parties and looser political movements were among the most frequently named specific domestic actors, followed by domestic Armenian media outlets.

Aside from these named organizations, TASS and Sputnik made ninety-one more generalized references to domestic Armenian non-governmental organizations, protesters, opposition groups, or groups and individuals during the same period. Coverage of domestic civic space actors, named or unnamed, was largely neutral (88 percent) or negative (9 percent), with only 6 positive references in the entire period. Russian state media accorded somewhat more negative coverage towards unnamed domestic actors such as “protesters,” “opposition activists,” and “demonstrators,” but on balance, the vast majority of mentions were generally moderate in tone.

The most frequently named domestic actor was the deliberately apolitical grassroots movement Say No to Robbery, also known as #ElectricYerevan, single-handedly accounted for 13 Russian state media mentions (Table 6). Coverage of the movement by TASS and Sputnik, which galvanized a broad cross-section of citizens to protest a hike in electricity prices in 2015, was largely neutral (62 percent) or positive (31 percent) in sentiment, at least in our sample of articles. It should be noted, however, that protest leaders at the time did express concern that the movement was being unfairly characterized by pro-Kremlin media as another “Maidan” or “color revolution” promoted from abroad. [21] In this respect, examining a broader set of print and electronic media could yield a somewhat different sentiment story.

Interestingly, we did not find any evidence of the Kremlin using Russian state-owned media as a megaphone to promote increased visibility of the Armenian civic space actors it supports financially or non-financially. [22] Possibly, the Kremlin may find it easier to borrow the credibility of domestic Armenian civic space actors if it is not overtly associated with these organizations in the media, hence why it may abstain from overly publicizing these linkages.

Alternatively, Russian leaders may view the use of these two tools as distinct in their function, but mutually reinforcing in their goals. The Kremlin’s provision of substantive support to individual civic actors may be best suited to subtly using local voices to advance pro-Russian values and views. Comparatively, Russian state media is a blunt instrument that may be most appropriate to selectively promote Moscow’s desired narratives related to broader events and more visible organizations.

Table 6. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in Armenia by Sentiment

|

Domestic Civic Group |

Extremely Negative |

Somewhat Negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat Positive |

Grand Total |

|

Protesters |

0 |

4 |

34 |

1 |

39 |

|

Opposition Activists |

1 |

3 |

20 |

0 |

24 |

|

Say No to Robbery |

0 |

1 |

8 |

4 |

13 |

|

Demonstrators |

0 |

2 |

7 |

1 |

10 |

|

Republican Party of Armenia (RPA) |

0 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

9 |

3.2.2 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in Armenian Civic Space

Russian state media dedicated the remaining mentions (70 instances) to external actors operating in Armenia’s civic space, including intergovernmental organizations (45 mentions), foreign organizations by name (16 mentions), and 9 generalized references to foreign actors. The most frequently mentioned external actors (Table 7) were involved in brokering peace in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict—such as the Organization for Security Co-operation in Europe (27 mentions) and the International Red Cross (3 mentions)—or serving as election monitors in Armenia the Commonwealth of Independent States (6 mentions). Named foreign organizations were comparatively infrequent and usually appeared as one-off mentions, often providing quotes about the state of current civic space affairs in Armenia.

Similar to domestic civic space actors, the preponderance of Russian state media coverage of intergovernmental and named foreign organizations was neutral, 80 and 75 percent, respectively. Nevertheless, generalized references to unnamed foreign actors—such as “foreign NGOs,” “Western NGOs,” and “Western media”—stand out for attracting a substantially higher degree of negative mentions (55 percent of instances). The substance of this coverage is noteworthy as it illuminates an important Kremlin influence strategy in Armenia of attempting to discredit domestic pro-Western or pro-democracy voices through oblique references that cast them as beholden to ‘the West.’

Table 7. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Armenia by Sentiment

|

External Civic Actors |

Extremely Negative |

Somewhat Negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat Positive |

Extremely Positive |

Grand Total |

|

Organization for Security Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) / Including Mentions of Minsk Group, Office for Democratic Institutions & Human Rights & Parliamentary Assembly |

0 |

3 |

18 |

6 |

0 |

27 |

|

Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) / Including Mentions of the Inter-Parliamentary Assembly, Election Observer Mission, and Countries Institute |

0 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

|

Armenian Diaspora |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

3.2.3 Russian State Media’s Focus on Armenia’s Civic Space over Time

As a general rule, Russian state media mentions of civic space actors tend to spike around specific events within E&E countries. This broader trend holds true in Armenia (Figure 15), with heightened Russian media mentions of civic space actors in relation to four important episodes in Armenian civic space: (i) 74 references to mass protests between June and September 2015 related to a hike in electricity prices (#ElectricYerevan); (ii) 44 mentions of anti-government protests opposing Serzh Sargsyan’s ruling Republican Party of Armenia (#MerzhirSerzhin, #RejectSerzh) in April to May 2018; (iii) 47 references to snap parliamentary elections in December 2018; and (iv) 65 mentions subsequent to the September 2020 outbreak of hostilities between Azerbaijan and Armenia in the Nagorno-Karabakh region.

Figure 15. Russian State Media Mentions of Armenian Civic Space Actors

Number of Mentions Recorded

3.2.4 Russian State Media Coverage of Western Institutions and Democratic Norms

In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of Armenia’s citizens, we analyzed the frequency and sentiment of coverage related to five keywords in conjunction with Armenia. [23] Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced all five keywords from January 2015 to March 2021 (Table 8). Russian state media mentioned the European Union (27 instances), the United States (114 instances), NATO (19 instances), the “West” (18 instances), and democracy (3 instances) with reference to Armenia during this period. Sixty-four percent of these mentions (117 instances) were neutral, with the remainder split between negative (24 percent) and positive coverage (11 percent). Notably, upticks in Russian state media coverage of the keywords in relation to Armenia appear to coincide with outbreaks of conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh—including an April 2016 clash of Armenian and Azerbaijani troops and the full-scale hostilities beginning in late September 2020 (Figure 16).

Table 8. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

|

Keyword |

Extremely negative |

Somewhat negative |

Neutral |

Somewhat positive |

Extremely positive |

Grand Total |

|

NATO |

3 |

4 |

10 |

2 |

0 |

19 |

|

European Union |

1 |

3 |

20 |

3 |

0 |

27 |

|

United States |

8 |

13 |

81 |

11 |

1 |

114 |

|

Democracy |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

|

West |

6 |

6 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

18 |

Figure 16. Keyword Mentions by Russian State Media in Relation to Armenia

Number of Unique Keyword Instances of NATO, the U.S., the EU, Democracy, and the West in Russian State Media

NATO and the European Union were the second and third most frequently mentioned keywords in reference to Armenia. Yerevan’s cooperation with NATO attracted a somewhat higher proportion of negative coverage (37 percent), though references were more tempered than observed in Georgia or North Macedonia, for example. Negative mentions of NATO warned of outbreaks of conflict, regional destabilization, and a global arms race that would arise from the bloc’s “military build-up” and increased activity in Eastern Europe. [24] Russian state media questioned the credibility of NATO as “brain-dead,” [25] “irritated” by the Nagorno-Karabakh ceasefire negotiated by Moscow, [26] and stoking fear about the “non-existent Russia threat” to justify the bloc’s continued relevance. [27] In parallel, the Kremlin sought to legitimize its own presence, referring to the joint defense system with Armenia as “countering the Western alliance’s military build-up near borders” and its role in helping its neighbors maintain their independence from NATO:

"The North Atlantic Alliance’s desire to lure Russia’s strategic partners into its ranks has long ceased to be a secret. We can see, however, that Serbia, which receives aid from us within the framework of military-technical cooperation, despite being surrounded by NATO countries, pursues a more balanced policy than Russia’s neighbors, which are dependent in terms of ensuring their national sovereignty. In light of that, it is strange to see Armenia, a CSTO member, taking part in the exercises of the military-political alliance whose members not only make aggressive statements about Russia but also expand the area of their military presence." [28]

Comparatively, Russian media coverage of the EU in relation to Armenia was more often neutral (74 percent) and less negative (15 percent). Negative mentions of the EU tended to cast aspersions on the bloc’s foreign policy as “based on colonialism and imperialism,” [29] and imposing a “vile either-or logic” which forces countries like Armenia to choose between Brussels or Moscow as their partner. [30] Similarly, the United States—which received the highest volume of mentions overall—also garnered largely neutral coverage (71 percent). Russian state media reserved many of its more negative mentions of the U.S. (18 percent) to cast doubt on the motives of the United States with regard to resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict: implying that Washington’s support to Azerbaijan was “a relic of the war on terrorism” [31] and that American and its allies were vexed by Moscow’s role in bringing about the ceasefire as this would frustrate their efforts to “push Russia out of Transcaucasia.” [32]

Democracy was mentioned least frequently in our sample of Russian state media, but when it was referenced in regard to Armenia it was generally positive or neutral, used to underscore Moscow’s commitment to helping Armenia resolve conflict through political dialogue [33] and interest in the country’s “stable and democratic development.” [34] Similar to dynamics in other E&E countries, Russian state media used the term “the West” (67 percent negative mentions) to inject fear about the motives of the U.S. and Europe writ large, warning against Western attempts to “provoke nationalists” in a bid to discredit the Nagorno-Karabakh ceasefire agreement, [35] instigate regime change with “anti-Russian…social protests” and “color revolution technologies,” [36] and “Western-bankrolled NGOs and media” attempts to drive a wedge between Moscow and Yerevan: [37]

"'In light of this, a reasonable question arises: why are problems in Russian-Armenian relations not being discussed by Russians and Armenians, but rather by Western-bankrolled NGOs and the media? What is the purpose of the authors of numerous "independent" studies on the detrimental consequences of deploying the Russian contingent to the republic, and, ultimately, who benefits from the destruction of the historical ties between the two states?” [38]

4. Conclusion

The data and analysis in this report reinforces a sobering truth: Russia’s appetite for exerting malign foreign influence abroad is not limited to Ukraine, and its civilian influence tactics are already observable in Armenia and elsewhere across the E&E region. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see clearly how the Kremlin invested its media, money, and in-kind support to promote pro-Russian sentiment within Armenia and discredit voices wary of its regional ambitions.

The Kremlin was adept in deploying multiple tools of influence in mutually reinforcing ways to amplify the appeal of closer integration with Russia, raise doubts about the motives of the U.S., EU, and NATO, as well as legitimize its actions as necessary to protect the region’s security from the disruptive forces of democracy. It used its cultural and language programming to bolster ties with Armenian youth and Russian compatriots. In parallel, Russian state media made a substantial effort to discredit domestic pro-Western or pro-democracy voices in Armenia by casting them as working at the behest of the U.S. or the EU.

Taken together, it is more critical than ever to have better information at our fingertips to monitor the health of civic space across countries and over time, reinforce sources of societal resilience, and mitigate risks from autocratizing governments at home and malign influence from abroad. We hope that the country reports, regional synthesis, and supporting dataset of civic space indicators produced by this multi-year project is a foundation for future efforts to build upon and incrementally close this critical evidence gap.

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

In this section, we provide a brief overview of the data and methods used in the creation of this country report and the underlying data collection upon which these insights are based. More in-depth information on the data sources, coding, and classification processes for these indicators is available in our full technical methodology available on aiddata.org.

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

AidData collected and classified unstructured information on instances of harassment or violence, restrictive legislation, and state-backed legal cases from three primary sources: (i) CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Armenia; (ii) RefWorld database of documents and news articles pertaining to human rights and interactions with civilian law enforcement in Armenia operated by UNHCR; and (iii) Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. AidData supplemented this data with country-specific information sources from media associations and civil society organizations who report on such restrictions. Restrictions that took place prior to January 1, 2015 or after March 31, 2021 were excluded from data collection. It should be noted that there may be delays in reporting of civic space restrictions. More information on the coding and classification process is available in the full technical methodology documentation.

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

Survey data on citizen perceptions of civic space were collected from three sources: the World Values Survey Wave 6, the Joint European Values Study and World Values Survey Wave 2017-2021, the Gallup World Poll (2010-2021). These surveys capture information across a wide range of social and political indicators. The coverage of the three surveys and the exact questions asked in each country vary slightly, but the overall quality and comparability of the datasets remains high.

The fieldwork for WVS Wave 6 in Armenia was conducted during September and October 2011 with a nationally representative sample of 1100 randomly selected adults residing in private homes, regardless of nationality or language. [39] The documentation does not specify the language that the survey was conducted in. Research team provided an estimated error rate of 3.0%. This weight is provided as a standard version for consistency with previous releases.” [40] The E&E region countries included in WVS Wave 6, which were harmonized and designed for interoperable analysis, were Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Ukraine. Regional means for the question “How interested you have been in politics over the last 2 years?” were first collapsed from “Very interested,” “Somewhat interested,” “Not very interested,” and “Not at all interested” into the two categories: “Interested” and “Not interested.” Averages for the region were then calculated using the weighted averages from the seven countries.

Regional means for the WVS Wave 6 question “Now I’d like you to look at this card. I’m going to read out some different forms of political action that people can take, and I’d like you to tell me, for each one, whether you have actually done any of these things, whether you might do it or would never, under any circumstances, do it: Signing a petition; Joining in boycotts; Attending lawful demonstrations; Joining unofficial strikes” were calculated using the weighted averages from the seven E&E countries as well.

The membership indicator uses responses to a WVS Wave 6 question which lists several voluntary organizations (e.g., church or religious organization, political party, environmental group). Respondents to WVS 6 could select whether they were an “Active member,” “Inactive member,” or “Don’t belong.” The values included in the profile are weighted in accordance with WVS recommendations. The regional mean values were calculated using the weighted averages from the seven countries included in a given survey wave. The values for membership in political parties, humanitarian or charitable organizations, and labor unions are provided without any further calculation, and the “Other community group” cluster was calculated from the mean of membership values in “Art, music or educational organizations,” “Environmental organizations,” “Professional associations,” “Church or other religious organizations,” “Consumer organizations,” “Sport or recreational associations,” “Self-help or mutual aid groups,” and “Other organizations.”

The confidence indicator uses responses to an WVS Wave 6 question which lists several institutions (e.g., church or religious organization, parliament, the courts and the judiciary, the civil service). Respondents to WVS 6 surveys could select how much confidence they had in each institution from the following choices: “A great deal,” “Quite a lot,” “Not very much,” or “None at all.” The “A great deal” and “Quite a lot” options were collapsed into a binary “Confident” indicator, while “Not very much” and “None at all” options were collapsed into a “Not confident” indicator. [41]

The fieldwork for EVS Wave 5 in Armenia was conducted in Armenian between February and April 2018 with a nationally representative sample of 1500 randomly selected adults residing in private homes, regardless of nationality or language. [42] The research team did not provide an estimated error rate for the survey data after applying a weighting variable “computed using the marginal distribution of age, sex, educational attainment, and region. This weight is provided as a standard version for consistency with previous releases.” [43]

The E&E region countries included in the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 dataset, which were harmonized and designed for interoperable analysis, were Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, and Ukraine. Regional means for the question “How interested have you been in politics over the last 2 years?” were first collapsed from “Very interested,” “Somewhat interested,” “Not very interested,” and “Not at all interested” into the two categories: “Interested” and “Not interested.” Averages for the region were then calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen countries.

Regional means for the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 question “Now I’d like you to look at this card. I’m going to read out some different forms of political action that people can take, and I’d like you to tell me, for each one, whether you have actually done any of these things, whether you might do it or would never, under any circumstances, do it: Signing a petition; Joining in boycotts; Attending lawful demonstrations; Joining unofficial strikes” were calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen E&E countries as well.

The membership indicator uses responses to a Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 question which lists several voluntary organizations (e.g., church or religious organization, political party, environmental group, etc.). Respondents to WVS 7 could select whether they were an “Active member,” “Inactive member,” or “Don’t belong.” The EVS 5 survey only recorded a binary indicator of whether the respondent belonged to or did not belong to an organization. For our analysis purposes, we collapsed the “Active member” and “Inactive member” categories into a single “Member” category, with “Don’t belong” coded to “Not member.” The values included in the profile are weighted in accordance with WVS and EVS recommendations. The regional mean values were calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen countries included in a given survey wave. The values for membership in political parties, humanitarian or charitable organizations, and labor unions are provided without any further calculation, and the “Other community group” cluster was calculated from the mean of membership values in “Art, music or educational organizations,” “Environmental organizations,” “Professional associations,” “Church or other religious organizations,” “Consumer organizations,” “Sport or recreational associations,” “Self-help or mutual aid groups,” and “Other organizations.”

The confidence indicator uses responses to a Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 question which lists several institutions (e.g., church or religious organization, parliament, the courts and the judiciary, the civil service, etc.). Respondents to the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 surveys could select how much confidence they had in each institution from the following choices: “A great deal,” “Quite a lot,” “Not very much,” or “None at all.” The “A great deal” and “Quite a lot” options were collapsed into a binary “Confident” indicator, while “Not very much” and “None at all” options were collapsed into a “Not confident” indicator. [44]

The Gallup World Poll was conducted annually in each of the E&E region countries from 2010-2021, except for the countries that did not complete fieldwork due to the coronavirus pandemic. Each country sample includes at least 1,000 adults and is stratified by population size and/or geography with clustering via one or more stages of sampling. In 2019 the survey was conducted with 1,080 adults rather than 1,000. The data are weighted to be nationally representative. The survey was conducted in Armenian each year from 2010 to 2021.

The Civic Engagement Index is an estimate of citizens’ willingness to support others in their community. It is calculated from positive answers to three questions: “Have you done any of the following in the past month? How about donated money to a charity? How about volunteered your time to an organization? How about helped a stranger or someone you didn’t know who needed help?” The engagement index is then calculated at the individual level, giving 33% to each of the answers that received a positive response. Armenia’s country values are then calculated from the weighted average of each of these individual Civic Engagement Index scores.

The regional mean is similarly calculated from the weighted average of each of those Civic Engagement Index scores, taking the average across all 17 E&E countries: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. The regional means for 2020 and 2021 are the exception. Gallup World Poll fieldwork in 2020 was not conducted for Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, and Turkmenistan. Gallup World Poll fieldwork in 2021 was not conducted for Azerbaijan, Belarus, Montenegro, and Turkmenistan.

5.3 Russian Projectized Support to Civic Space Actors or Regulators