Albania: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence

Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, Lincoln Zaleski

April 2023

[Skip to Table of Contents] [Skip to Chapter 1]Executive Summary

This report surfaces insights about the health of Albania’s civic space and vulnerability to malign foreign influence in the lead up to Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Research included extensive original data collection to track Russian state-backed financing and in-kind assistance to civil society groups and regulators, media coverage targeting foreign publics in the region, and indicators to assess domestic attitudes to civic participation and restrictions of civic space actors. Crucially, this report underscores that the Kremlin’s influence operations were not limited to Ukraine alone and illustrates its use of civilian tools in Albania to co-opt support and deter resistance to its regional ambitions.

The analysis was part of a broader three-year initiative by AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—to produce quantifiable indicators to monitor civic space resilience in the face of Kremlin influence operations over time (from 2010 to 2021) and across 17 countries and 7 occupied or autonomous territories in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). Below we summarize the top-line findings from our indicators on the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Albania, as well as channels of Russian malign influence operations:

- Restrictions of Civic Actors: Albanian civic space actors were the targets of 86 restrictions between January 2017 and March 2021, including harassment or violence (72 percent), restrictive legislation (19 percent) and state-backed legal cases (9 percent). Thirty-seven percent of restrictions were in a single year, 2020. Journalists critical of the government were most frequently targeted and the Albanian government was the primary initiator, though a number of incidents involved domestic non-governmental actors and unidentified assailants. In the one recorded instance involving a foreign government, the Albanian foreign ministry denied a Turkish national asylum, extraditing him instead.

- Attitudes Towards Civic Participation: Only 30 percent of Albanians were interested in politics in 2018 and only a minority had participated in a petition (12 percent), demonstration (7 percent) or boycott (4 percent). That said, Albanians were decidedly more willing than regional peers to discuss political issues with friends or on social media. Albanians had low rates of membership in voluntary organizations and had low levels of confidence in their institutions (14 percent), except for the military, police, and religious groups. Nevertheless, Albanians found alternative avenues to offer practical support to their fellow citizens. In 2020, 58 percent of Albanians helped a stranger and 31 percent donated to charity. Volunteerism was the weakest performing metric (11 percent).

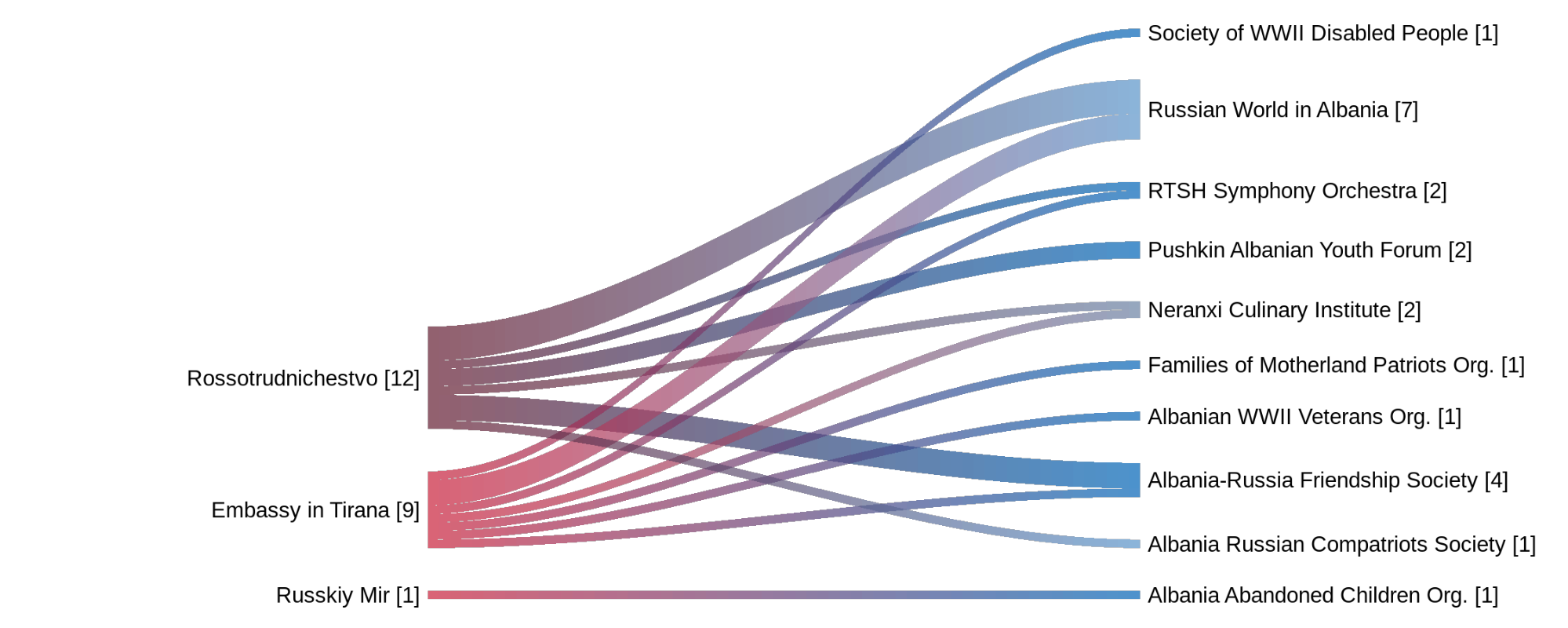

- Russian-backed Civic Space Projects: The Kremlin supported 10 Albanian civic organizations via 12 projects between January 2015 and August 2021. Russian linguistic and cultural ties, engagement with youth groups, and outreach to Russian compatriots and veterans were the primary focus areas. However, there was a noticeable absence of Kremlin support for local police and military-patriotic secondary schools, religious programming, and an emphasis on shared history as seen in other countries. The Kremlin’s activities were almost exclusively oriented to Tirana, and engagement unusually limited to three Russian actors: Rossotrudnichestvo, the Russian Embassy-Tirana, and Russkiy Mir Foundation.

- Russian State-run Media: Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News referenced Albanian civic actors 30 times from January 2015 to March 2021. Media outlets were the most frequently mentioned domestic actors by name and the overall tone of mentions was largely neutral. Negative coverage was predominantly directed towards Albanian minority opposition groups operating in North Macedonia, which the Kremlin portrayed as extremist, and characterized the EU,U.S., and “the West” as meddlers enabling the “Albanization of the Balkans.”

Table of Contents

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Albania

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Albania: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

2.2 Attitudes Toward Civic Space in Albania

2.2.1 Interest in Politics and Willingness to Act as Barometers of Albanian Civic Space

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to Albania’s Civic Space

3.1.1 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Albania’s Civic Space

3.1.2 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Albania's Civic Space

3.2 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

3.2.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Albanian Civic Space Actors

3.2.2 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in Albanian Civic Space

3.2.3 Russian State Media’s Focus on Albania’s Civic Space over Time

3.2.4 Russian State Media Coverage of Western Institutions and Democratic Norms

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

5.3 Russian Projectized Support to Civic Space Actors or Regulators

5.4 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

Figures and Tables

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of Albanian Civic Space Actors

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Albania

Figure 2. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Albania

Figure 3. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Albania by Initiator

Figure 4. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Albania by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Figure 5. Threatened versus Acted-on Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Albania

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Albania

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Albania

Figure 7. Political Action: Participation by Albanian Citizens versus Balkan Peers, 2016 and 2018

Figure 8. Political Action: Albanian Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2018

Figure 9. Interest in Politics: Albanian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2018

Figure 10. Political Action: Participation by Albanian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2018

Figure 11. Voluntary Organization Membership: Albanian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2018

Figure 13. Civic Engagement Index: Albania versus Regional Peers

Figure 14. Russian Projects Supporting Albanian Civic Space Actors by Type

Figure 15. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Albanian Civic Space

Figure 16. Locations of Russian Support to Albanian Civic Space

Table 5. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in Albania by Sentiment

Table 6. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Albania by Sentiment

Figure 17. Russian State Media Mentions of Albanian Civic Space Actors

Table 7. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Samantha Custer, Divya Mathew, Bryan Burgess, Emily Dumont, and Lincoln Zaleski. John Custer, Sariah Harmer, Parker Kim, and Sarina Patterson contributed editing, formatting, and supporting visuals. Kelsey Marshall and our research assistants provided invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report including: Jacob Barth, Kevin Bloodworth, Callie Booth, Catherine Brady, Temujin Bullock, Lucy Clement, Jeffrey Crittenden, Emma Freiling, Cassidy Grayson, Annabelle Guberman, Sariah Harmer, Hayley Hubbard, Hanna Kendrick, Kate Kliment, Deborah Kornblut, Aleksander Kuzmenchuk, Amelia Larson, Mallory Milestone, Alyssa Nekritz, Megan O’Connor, Tarra Olfat, Olivia Olson, Caroline Prout, Hannah Ray, Georgiana Reece, Patrick Schroeder, Samuel Specht, Andrew Tanner, Brianna Vetter, Kathryn Webb, Katrine Westgaard, Emma Williams, and Rachel Zaslavsk. The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

This research was made possible with funding from USAID's Europe & Eurasia (E&E) Bureau via a USAID/DDI/ITR Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) cooperative agreement (AID-A-12-00096). The findings and conclusions of this country report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

A Note on Vocabulary

The authors recognize the challenge of writing about contexts with ongoing hot and/or frozen conflicts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consistently label groups of people and places for the sake of data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that terminology is political, but our use of terms should not be construed to mean support for one faction over another. For example, when we talk about an occupied territory, we do so recognizing that there are de facto authorities in the territory who are not aligned with the government in the capital. Or, when we analyze the de facto authorities’ use of legislation or the courts to restrict civic action, it is not to grant legitimacy to the laws or courts of separatists, but rather to glean meaningful insights about the ways in which institutions are co-opted or employed to constrain civic freedoms.

Citation

Custer, S., Mathew, D., Burgess, B., Dumont, E., Zaleski, L. (2023). Albania: Measuring civic space risk, resilience, and Russian influence. April 2023. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William and Mary.

1. Introduction

How strong or weak is the domestic enabling environment for civic space in Albania? To what extent do we see Russia attempting to shape civic space attitudes and constraints in Albania to advance its broader regional ambitions? Over the last three years, AidData—a research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute—has collected and analyzed vast amounts of historical data on civic space and Russian influence across 17 countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia (E&E). [1] In this country report, we present top-line findings specific to Albania from a novel dataset which monitors four barometers of civic space in the E&E region from 2010 to 2021 (Table 1). [2]

For the purpose of this project, we define civic space as: the formal laws, informal norms, and societal attitudes which enable individuals and organizations to assemble peacefully, express their views, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. [3] Here we provide only a brief introduction to the indicators monitored in this and other country reports. However, a more extensive methodology document is available via aiddata.org which includes greater detail about how we conceptualized civic space and operationalized the collection of indicators by country and year.

Civic space is a dynamic rather than static concept. The ability of individuals and organizations to assemble, speak, and act is vulnerable to changes in the formal laws, informal norms, and broader societal attitudes that can facilitate an opening or closing of the practical space in which they have to maneuver. To assess the enabling environment for Albanian civic space, we examined two indicators: restrictions of civic space actors (section 2.1) and citizen attitudes towards civic space (section 2.2). Because the health of civic space is not strictly a function of domestic dynamics alone, we also examined two channels by which the Kremlin could exert external influence to dilute democratic norms or otherwise skew civic space throughout the E&E region. These channels are Russian state-backed financing and in-kind support to government regulators or pro-Kremlin civic space actors (section 3.1) and Russian state-run media mentions related to civic space actors or democracy (section 3.2).

Since restrictions can take various forms, we focus here on three common channels which can effectively deter or penalize civic participation: (i) harassment or violence initiated by state or non-state actors; (ii) the proposal or passage of restrictive legislation or executive branch policies; and (iii) state-backed legal cases brought against civic actors. Citizen attitudes towards political and apolitical forms of participation provide another important barometer of the practical room that people feel they have to engage in collective action related to common causes and interests or express views publicly. In this research, we monitored responses to citizen surveys related to: (i) interest in politics; (ii) past participation and future openness to political action (e.g., petitions, boycotts, strikes, protests); (iii) trust or confidence in public institutions; (iv) membership in voluntary organizations; and (v) past participation in less political forms of civic action (e.g., donating, volunteering, helping strangers).

In this project, we also tracked financing and in-kind support from Kremlin-affiliated agencies to: (i) build the capacity of those that regulate the activities of civic space actors (e.g., government entities at national or local levels, as well as in occupied or autonomous territories ); and (ii) co-opt the activities of civil society actors within E&E countries in ways that seek to promote or legitimize Russian policies abroad. Since E&E countries are exposed to a high concentration of Russian state-run media, we analyzed how the Kremlin may use its coverage to influence public attitudes about civic space actors (formal organizations and informal groups), as well as public discourse pertaining to democratic norms or rivals in the eyes of citizens.

Although Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine February 2022 undeniably altered the civic space landscape in Albania and the E&E region for years to come, the historical information in this report is still useful in three respects. By taking the long view, this report sheds light on the Kremlin’s patient investment in hybrid tactics to foment unrest, co-opt narratives, demonize opponents, and cultivate sympathizers in target populations as a pretext or enabler for military action. Second, the comparative nature of these indicators lends itself to assessing similarities and differences in how the Kremlin operates across countries in the region. Third, by examining both domestic and external factors in tandem, this report provides a more holistic view of how to support resilient societies in the face of autocratizing forces at home and malign influence from abroad.

Table 1. Quantifying Civic Space Attitudes and Constraints Over Time

|

Civic Space Barometer |

Supporting Indicators |

|

Restrictions of civic space actors (January 2017–March 2021) |

|

|

Citizen attitudes toward civic space (2010–2021)

|

|

|

Russian projectized support relevant to civic space (January 2015–August 2021) |

|

|

Russian state media mentions of civic space actors (January 2015–March 2021) |

|

Notes: Table of indicators collected by AidData to assess the health of Albania’s domestic civic space and vulnerability to Kremlin influence. Indicators are categorized by barometer (i.e., dimension of interest) and specify the time period covered by the data in the subsequent analysis.

2. Domestic Risk and Resilience: Restrictions and Attitudes Towards Civic Space in Albania

A healthy civic space is one in which individuals and groups can assemble peacefully, express views and opinions, and take collective action without fear of retribution or restriction. Laws, rules, and policies are critical to this space, in terms of rights on the books (de jure) and how these rights are safeguarded in practice (de facto). Informal norms and societal attitudes are also important, as countries with a deep cultural tradition that emphasizes civic participation can embolden civil society actors to operate even absent explicit legal protections. Finally, the ability of civil society actors to engage in activities without fear of retribution (e.g., loss of personal freedom, organizational position, and public status) or restriction (e.g ., constraints on their ability to organize, resource, and operate) is critical to the practical room they have to conduct their activities. If fear of retribution and the likelihood of restriction are high, this has a chilling effect on the motivation of citizens to form and participate in civic groups.

In this section, we assess the health of civic space in Albania over time in two respects: the volume and nature of restrictions against civic space actors (section 2.1) and the degree to which Albanians engage in a range of political and apolitical forms of civic life (section 2.2).

2.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Albania: Targets, Initiators, and Trends Over Time

Albanian civic space actors experienced 86 known restrictions between January 2017 and March 2021 (see Table 2). These restrictions were weighted toward instances of harassment or violence (72 percent). There were fewer instances of state-backed legal cases (9 percent) and newly proposed or implemented restrictive legislation (19 percent); however, these instances can have a multiplier effect in creating a legal mandate for a government to pursue other forms of restriction. These imperfect estimates are based upon publicly available information either reported by the targets of restrictions, documented by a third-party actor, or covered in the news (Section 5). [4]

Table 2. Recorded Restrictions of Albanian Civic Space Actors

|

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021-Q1 |

Total |

|

Harassment/Violence |

12 |

8 |

18 |

23 |

1 |

62 |

|

Restrictive Legislation |

0 |

5 |

5 |

6 |

0 |

16 |

|

State-backed Legal Cases |

3 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

8 |

|

Total |

15 |

14 |

24 |

32 |

1 |

86 |

Notes: Table of the number of restrictions initiated against civic space actors in Albania, disaggregated by type and year. Sources: CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Albania and Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Data manually collected by AidData staff and research assistants.

Instances of restrictions of Albanian civic space actors were unevenly distributed across this time period and on the rise from 2017 to 2020, only 1 restriction was recorded in the first quarter of 2021 (Figure 1). Thirty-seven percent of cases were recorded in 2020 alone, coinciding with unrest in the wake of COVID-related restrictions. There were restrictions of members of the media who reported on the government’s handling of the pandemic, as well as targeted attacks of journalists who wrote investigative pieces linking government officials to corruption. In December 2020, there were massive protests following the fatal police shooting of 25-year-old Klodian Rasha. Police clashed with the protestors and obstructed journalists covering the events. Journalists and members of the media were the most frequent targets of violence and harassment, accounting for 63 percent of all recorded instances (Figure 2), followed by the category “other” [5] and members of the political opposition.

Figure 1. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Albania

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment/Violence

Restrictive Legislation

State-backed Legal Cases

Key Events Relevant to Civic Space in Albania

|

February 2017 |

Albania's main opposition, the Democratic Party, boycotts parliament, protesting for free and fair elections. They demand a caretaker cabinet to hold the June 18 elections. |

|

June 2017 |

Parliamentary elections are held, and Socialist PM Edi Rama wins a second term. The opposition center-right Democratic Party is led by Lulzim Basha. |

|

December 2017 |

Arta Marku is elected acting chief prosecutor, while police clash with roughly 3,000 opposition supporters who try to enter parliament and disrupt the vote. |

|

April 2018 |

The opposition blocks Albania's main highway junctions in protest, accusing government officials of links to organized crime and increasing taxes and poverty. |

|

December 2018 |

Thousands of university students protest in Tirana, demanding lower tuition fees and more investment in public education. PM Rama shuffles his Cabinet in response. |

|

March 2019 |

Thousands of opposition protesters try to enter parliament, calling for the government's resignation. President Ilir Meta says he would resign, or even kill himself, if it would resolve Albania's political crisis. |

|

June 2019 |

President Meta calls off local elections set for June 30. The government accuses him of breaking the law and declares he should be impeached. |

|

March 2020 |

The EU's executive says Albania and North Macedonia have done enough to merit starting negotiations for membership. |

|

December 2020 |

Violent protests follow the fatal police shooting of 25-year-old Klodian Rasha, who reportedly ignored officers' calls to stop and ran away. |

|

|

|

Figure 2. Harassment or Violence by Targeted Group in Albania

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2017–March 2021

The Albanian government was the most prolific initiator of restrictions of civic space actors, accounting for 46 recorded mentions. The instances of restriction included verbal abuse of journalists, often by government officials, and police actions to disperse and detain protestors (Figure 3). Domestic non-governmental actors were identified as initiators in 9 restrictions and there were some incidents involving unidentified assailants (9 mentions). By virtue of the way that the indicator was defined, the initiators of state-backed legal cases are either explicitly government agencies and government officials or clearly associated with these actors (e.g., the spouse or immediate family member of a sitting official).

Figure 3. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Albania by Initiator

Number of instances recorded

There was only one recorded instances of restrictions of civic space actors during this period involving a foreign government:

- Selami Simsek, a Turkish national accused of being part of the Gulenist network, was held by the Albanian Interior Ministry in March 2020. Simsek had sought political asylum but was denied. The ministry was preparing to extradite him.

Figure 4 breaks down the targets of restrictions by political ideology or affiliation in the following categories: pro-democracy, pro-Western, and anti-Kremlin. [6] Pro-democracy organizations and activists were mentioned 15 times as targets of restriction during this period. [7] Pro-Western organizations and activists were mentioned 10 times as targets of restrictions. [8] There were no instances where we identified the target organizations or individuals to be explicitly anti-Kremlin in their public views. [9] It should be noted that this classification does not imply that these groups were targeted because of their political ideology or affiliation, merely that they met certain predefined characteristics. In fact, these tags were deliberately defined narrowly such that they focus on only a limited set of attributes about the organizations and individuals in question.

Figure 4. Restrictions of Civic Space Actors in Albania by Political or Ideological Affiliation

Number of Instances Recorded

Harassment/Violence

State-backed Legal Cases

2.1.1 Nature of Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

Instances of harassment (1 threatened, 28 acted upon) towards civic space actors were less common than episodes of outright physical harm (4 threatened, 29 acted upon) during the period. The vast majority of these restrictions (92 percent) were acted on, rather than merely threatened. However, since this data is collected based on reported incidents, this likely understates threats which are less visible (see Figure 5). Of the 62 instances of harassment and violence, acted-on violence accounted for the largest percentage (47 percent).

Figure 5. Threatened versus Acted-on Harassment or Violence Against Civic Space Actors in Albania

Number of Instances Recorded

Recorded instances of restrictive legislation (16) in Albania are important to capture as they give government actors a mandate to constrain civic space with long-term cascading effects. This indicator is limited to a subset of parliamentary laws, chief executive decrees or other formal executive branch policies and rules that may have a deleterious effect on civic space actors, either subgroups or in general. Both proposed and passed restrictions qualify for inclusion, but we focus exclusively on new and negative developments in laws or rules affecting civic space actors. We exclude discussion of pre-existing laws and rules or those that constitute an improvement for civic space.

Taking a closer look at instances of restrictive legislation, the Albanian government used a two-pronged approach to constrain civic space: (i) impeding the ability of CSOs to organize and raise funds; and (ii) wielding anti-defamation as a weapon to police and deter media content critical of the administration:

- Five recorded laws imposed, intentionally or otherwise, may create a chilling effect on civic participation including: the Law on Accounting and Financial Statements (May 2018); Amendments to the Law for Social Enterprises in the Republic of Albania (August 2018); Amendments to the Law on Non Profit Organizations and the Law on Tax Procedures (December 2018); the Law for the Supervision of the Non-for-profit organizations in the Function of Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism (July 2019); and the Law For Youth (December 2019). Although when applied consistently and fairly, these laws can provide beneficial improvements to the transparency of civic actors, there are examples throughout the region where similar legislation has been applied selectively to restrict the activities of pro-democracy or opposition voices.

- Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama proposed an “anti-defamation” legislative package in 2018 which would require websites to register with the government to be deemed legal and sought stronger regulation of online content via a “Complaints Council” with the mandate to penalize, close or block access to online media based upon third-party requests. Lawmakers passed the package in December 2019, despite criticism from freedom of speech advocates. Although Albanian President Ilir Meta withheld his approval, asking the Venice Commission to weigh in on the law’s constitutionality, the ruling majority in parliament announced plans to overrule the presidential veto in January 2020.

Civic space actors were the targets of 8 recorded instances of state-backed legal cases between January 2017 and March 2021, the highest volume in 2017 and 2020. [10] Journalists were most often the defendants (Table 3), charged in connection with their reporting on links between government officials and unscrupulous business connections. There were no recorded cases against formal CSOs or NGOs. As shown in Figure 6, charges were directly (100 percent) tied to fundamental freedoms (e.g., freedom of speech, assembly) as opposed to indirect nuisance charges (e.g., fraud, embezzlement, tax evasion) often used by regimes in other countries to discredit the reputations of civic space actors.

Table 3. State-Backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Albania

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2017–March 2021

|

Defendant Category |

Number of Cases |

|

Media/Journalist |

4 |

|

Political Opposition |

1 |

|

Formal CSO/NGO |

0 |

|

Individual Activist/Advocate |

0 |

|

Other Community Group |

0 |

|

Other |

3 |

Figure 6. Direct versus Indirect State-backed Legal Cases by Targeted Group in Albania

Number of Instances Recorded, January 2017–March 2021

2.2 Attitudes Toward Civic Space in Albania

Albanian citizens reported consistently low rates of interest in politics and membership in voluntary organizations. Compared to their regional peers, Albanians viewed their parliament and political parties as particularly corrupt. Nevertheless, Albanians found alternative avenues to offer practical support to their fellow citizens, with an uptick in charitable donations and helping strangers coinciding with parliamentary elections in 2013 and the COVID-19 pandemic. In this section, we take a closer look at Albanian citizens’ interest in politics, participation in political action or voluntary organizations, and confidence in institutions. We also examine how Albanians’ involvement in less political forms of civic engagement—donating to charities, volunteering for organizations, helping strangers—has evolved over time.

2.2.1 Interest in Politics and Willingness to Act as Barometers of Albanian Civic Space

In 2016, a minority of Albanians engaged in protests or commented on political issues on social media (7 percent) or otherwise engaged in public debates (3 percent), according to the Balkan Barometer survey (Figure 7). Thirty-nine percent of Albanians said their political activity was limited to discussing issues with their friends and a further 37 percent did not even do this. By 2018, there was a movement towards greater political participation, driven by a shift away from respondents reporting no activity at all (-16 percentage points) towards being willing to discuss political issues with friends, engage in political conversations on social media, join in protests or participate in public debates (+4-6 percentage points per category).

Figure 7. Political Action: Participation by Albanian Citizens versus Balkan Peers, 2016 and 2018

Percentage of Respondents Reporting “Have Done”

The World Values Survey (WVS), [11] conducted in Albania in 2018, found similar levels of engagement in a separate set of political activities (Figure 8), with a minority of Albanian respondents reporting that they had signed a petition (12 percent), joined a demonstration (7 percent) or participated in a boycott (4 percent). An additional 30 to 47 percent of respondents said that they might take part in these activities in the future. Strikes lagged behind, with only 1 percent of respondents having previously taken part, and very few (3 percent) willing to do so in future.

Figure 8. Political Action: Albanian Citizens’ Willingness to Participate, 2018

Only 30 percent of Albanian respondents to the WVS expressed interest in politics, trailing their regional peers by 7 percentage points (Figure 9). [12] Comparatively, Albanians were also less likely to have engaged with petitions, boycotts, demonstrations, and strikes (-2 to 5 percentage points) than elsewhere in the region (Figure 10). Yet, there are some important exceptions to this trend. Albanians were more likely than counterparts in other Balkans countries to have discussed political issues with their friends (+17 percentage points), joined in protests [13] or commented on such issues via social media (+4-6 percentage points), according to the 2018 Balkan Barometer survey. [14]

Figure 9. Interest in Politics: Albanian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2018

Figure 10. Political Action: Participation by Albanian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2018

Percentage of Respondents Reporting “Have Done”

Albanians were much less likely to be members of voluntary organizations or volunteer their time to these institutions than their peers across the E&E region. Even the most popular organization types had only three percent of Albanian respondents identifying as members (Figure 11). This low level of participation may partly reflect a broader crisis of confidence among Albanians about the state of their institutions. A mere 14 percent of the population reported confidence in Albania’s government and overall confidence in the country’s institutions trailed the region by 16 percentage points. Over two-thirds of Albanian respondents to the WVS viewed their political parties and the parliament as corrupt and only a minority (6-8 percent) expressed confidence in these institutions.

Figure 11. Voluntary Organization Membership: Albanian Citizens versus Regional Peers, 2018

Table 4. Albanian Citizens’ Membership in Voluntary Organizations by Type versus Regional Peers, 2018

|

Voluntary Organization |

Albanian Membership, 2018 |

Regional Mean Membership, 2018 |

Percentage Point Difference |

|

Church or Religious Organization |

3% |

11% |

-9 |

|

Sport or Recreational Organization |

3% |

10% |

-7 |

|

Art, Music or Educational Organization |

3% |

9% |

-6 |

|

Labor Union |

0% |

11% |

-11 |

|

Political Party |

2% |

8% |

-6 |

|

Environmental Organization |

2% |

4% |

-3 |

|

Professional Association |

1% |

5% |

-4 |

|

Humanitarian or Charitable Organization |

2% |

6% |

-4 |

|

Consumer Organization |

0% |

3% |

-3 |

|

Self-Help Group, Mutual Aid Group |

2% |

4% |

-3 |

|

Other Organization |

2% |

4% |

-3 |

The only institutions that had the confidence of the majority of Albanians in 2018 were the military, the police, and religious groups. Sixty-nine percent of Albanian respondents perceived the military as honest. Despite low levels of volunteering or membership, Albanians viewed religious establishments and NGOs more favorably than other institutions. Respondents in Albania also trusted the private sector businesses (58 percent) more than did their regional peers (48 percent) in the Balkans.

Albanians’ primary reason why they were not actively involved in government decision-making shifted somewhat over the period. In 2016, 29 percent of Albanian respondents to the Balkan Barometer said they did not care [about these issues] (Figure 12), reporting a much higher degree of apathy than regional peers (+10 percentage points). By 2018, Albanians were most likely to say that they disengaged from political activity because they felt unable to influence government decisions. [15]

Figure 12. Political Activity: Reason for Non-Involvement, Albania versus Balkan Peers, 2016 and 2018

2.2.2 Apolitical Participation

The Gallup World Poll’s (GWP) Civic Engagement Index affords an additional perspective on Albanian citizens’ attitudes towards less political forms of participation between 2010 and 2021. This index measures the proportion of citizens that reported giving money to charity, volunteering at organizations, and helping a stranger on a scale of 0 to 100. [16] Overall, Albania charted the highest civic engagement in the two periods of 2013-2018 and 2020-21, following corresponding lows from 2010-2012 and 2019.

Donating to charity in Albania appeared to be the main index component driving this variability and appeared to be positively correlated with economic performance. [17] When the economy performed better, Albanian citizens may have felt more secure in donating money to charitable causes, though this did not extend to volunteering their time. Taken together with the previous section, Albanians may have low levels of formal organizational membership or volunteerism, but they have found alternative avenues to offer practical support to their fellow citizens via charitable donations and helping strangers.

Towards the start of the period (2010-2012), Albania’s civic engagement score trailed the regional average—14 to 25 points, respectively (Figure 13). During this three-year period, 11 percent of Albanian respondents reportedly gave money to charity, 7 percent volunteered at an organization, and 24 percent helped a stranger. [18] Albania’s civic engagement scores saw a sharp increase in 2013, with 56 percent of Albanians reporting that they had helped a stranger (+31 percentage points from 2012), catapulting the country into the middle of the region’s rankings. This uptick in engagement could be a positive spillover related to the country’s 2013 parliamentary elections, [19] similar to a pattern of heightened civic engagement activity around Serbia’s elections in 2014. [20] Nevertheless, any post-election boost likely had to do more with the elections in 2013 uniquely creating beneficial conditions and optimism for broader societal change, [21] as there was no corresponding increase in civic engagement during the 2017 elections.

Albania’s civic engagement receded again in 2019, before rallying in 2020 and 2021. Albania’s 2020 index score improved by 10 points compared to the previous year in the wake of not one, but two crises—the November 2019 earthquake and the 2020 arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, 58 percent of Albanians reported helping a stranger and 31 percent donated to charity. Albanians also increased their level of volunteerism by 7 percentage points (to 11 percent) as compared to the prior year. Albania’s civic engagement scores held steady in 2021 but did not grow as it did elsewhere in the region. This upward trend is consistent with improving civic engagement around the world as citizens rallied in response to COVID-19, even in the face of lockdowns and limitations on public gatherings. But it remains to be seen as to whether this initial improvement will be sustained in future.

Figure 13. Civic Engagement Index: Albania versus Regional Peers

3. External Channels of Influence: Kremlin Civic Space Projects and Russian State-Run Media in Albania

Foreign governments can wield civilian tools of influence such as money, in-kind support, and state-run media in various ways that disrupt societies far beyond their borders. They may work with the local authorities who design and enforce the prevailing rules of the game that determine the degree to which citizens can organize themselves, give voice to their concerns, and take collective action. Alternatively, they may appeal to popular opinion by promoting narratives that cultivate sympathizers, vilify opponents, or otherwise foment societal unrest. In this section, we analyze data on Kremlin financing and in-kind support to civic space actors or regulators in Albania (section 3.1), as well as Russian state media mentions related to civic space, including specific actors and broader rhetoric about democratic norms and rivals (section 3.2).

3.1 Russian State-Backed Support to Albania’s Civic Space

The Kremlin supported 10 known Albanian civic organizations via 12 civic space-relevant projects in Albania during the period of January 2015 to August 2021. [22] Moscow prefers to directly engage and build relationships with individual civic actors, as opposed to investing in broader based institutional development. In line with its strategy elsewhere, the Kremlin emphasized promoting Russian linguistic and cultural engagement with youth groups, outreach to Russian compatriots, and commemoration of veterans. The Russian government’s investments in cultivating these relationships with Albanian civic actors peaked in 2017 (Figure 14), dropping off in 2018 and beyond.

Figure 14. Russian Projects Supporting Albanian Civic Space Actors by Type

Number of Projects Recorded, January 2015–August 2021

The Kremlin routed its engagement in Albania between 2015 and 2018 through 3 different channels (Figure 15), which included the Rossotrudnichestvo federal center, [23] the state-owned Russkiy Mir Foundation, [24] and the Russian embassy in Tirana. The stated missions of these three entities focus on education and culture, promoting the Russian language, and public diplomacy. However, the Kremlin’s engagement with Albanian civic space actors came to an abrupt stop in 2018, as relations between the two countries soured over Albania’s decision to expel Russian diplomats in March 2018 [25] and an April 2018 EU Commission recommendation to open accession negotiations with Albania. [26] The final instance of identified Kremlin support to Albanian organizations was in October 2018, during the Albania-Russia Friendship Society and the Pushkin Albanian Youth Forum’s Unity Day celebrations. [27]

Rossotrudnichestvo and the Embassy in Tirana collectively supported 11 of the Kremlin’s 12 identified civic space-relevant projects identified in Albania. [28] The two Russian organs typically partnered with Albanian organizations to host public events showcasing Russian language or history, either working together to jointly support 4 projects or working independently. In cases where the Embassy provided sole support for Albanian organizations, this most often took the form of celebrations for veterans and donating books alongside the Albania-Russia Friendship Society. In parallel, Rossotrudnichestvo hosted poetry readings, a compatriot conference, photo exhibitions, and a Russian film night.

Russkiy Mir primarily partners with schools and individual Russian language teachers to promote Russian education. Occasionally, however, Russkiy Mir engages more directly with civil society organizations, as it did in the case of the Organization for the Support of Albania’s Abandoned Children. In 2017, Russkiy Mir donated the proceeds of its sales at the Charity Christmas Festival in Tirana to the Albanian charity.

In a sharp contrast with trends elsewhere in the region, where Kremlin support to local police and “military-patriotic” secondary schools is commonplace, none of the identified Russian organizations in Albania had a relationship to security or security-related training. This could indicate a lack of demand for this type of support from Albania, which typically has looked to the EU for police cooperation and NATO for security assistance.

Figure 15. Kremlin-affiliated Support to Albanian Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

3.1.1 The Recipients of Russian State-Backed Support to Albania’s Civic Space

The recipients of Russian state-backed support were relatively few in number (10) compared to elsewhere in the region, though included similar groups: formal civil society organizations (CSOs), compatriot unions for the Russian diaspora in Albania, [29] and a symphony orchestra. While domestic government institutions play an important role in maintaining and defining civic space and are a frequent recipient of Russian support elsewhere in the region, we identified no Albanian government bodies that received support relevant to civic space during the period from 2015 to 2021.

Ninety percent of the Albanian recipient organizations worked in the education and culture sector (9 organizations), promoting Russian language, history, and increased cooperation between Albania and Russia. This includes the Albania-Russia Friendship Society and the Pushkin Albanian Youth Forum, which co-hosted an event with Rossotrudnichestvo to celebrate Russia’s Unity Day. The event included a photo exhibition, a documentary about the holiday, and a quiz for attendees on the history and geography of Russia. Similarly, the compatriot union Russian World in Albania organized WWII Victory Day celebrations with the Embassy in Tirana in 2017. The participants shared stories of their family members who fought and released balloons with the Ribbon of St. George.

Russia collaborated with three Albanian veterans’ organizations: the Organization of Veterans of the Anti-Fascist National Liberation Struggle of the Albanian People, the Society of Disabled People of the National Liberation Struggle, and the Organization of Families of Patriots who gave their lives for the Motherland. These Albanian organizations all commemorated veterans and their family members and promoted education on the history of WWII. The Russian Embassy celebrated the 2015 Victory Day with these three organizations, presenting medals to veterans, as well as the organizations themselves.

Although compatriot unions and Russophile CSOs are the Kremlin’s most frequent willing partners in other countries, Rossotrudnichestvo and the Embassy in Tirana went farther afield in Albania to expand the reach of Russian cultural programming. They partnered with the Neranxi Culinary Institute in November 2016 for a presentation of Russian cuisine and sponsored a performance of Russian and Tatar music by the RTSH Symphony Orchestra in October 2017. These forays into broader cultural affairs ended in 2018 as Albania drew closer to the EU and the Kremlin directed its efforts elsewhere. Although the Kremlin often partners closely with Orthodox religious organizations elsewhere in the region, this emphasis on religious programming was noticeably absent in Albania, perhaps recognizing that the local Orthodox population trails majority Sunni and minority Roman Catholic congregations.

Geographically, Russia’s civic space overtures (11 of 12 projects) were almost exclusively oriented towards Tirana (Figure 16), with a fairly limited reach outside of the capital city. One of the Kremlin’s most frequent partners, Russian World in Albania, has offices on Rruga Pjetër Bogdani, only a few blocks from the Russian Embassy. [30] The one exception to this emphasis on Tirana, was a film series co-hosted by Rossotrudnichestvo and the Albania-Russia Friendship Society which took place in Berat in 2016. The film series sparked some discussion of further bilateral cultural and humanitarian initiatives between Russia and Albania in the city but did not appear to generate any measurable follow-on cooperation.

Figure 16. Locations of Russian Support to Albanian Civic Space

Number of Projects, 2015–2021

3.1.2 Focus of Russian State-Backed Support to Albania's Civic Space

Russian government support to Albanian civic space organizations appeared to be exclusively in the form of non-financial (e.g., event support or in-kind donations) support, as none of the projects explicitly referenced financing. Topically, the Kremlin focused its activities in Albania almost entirely on promoting Russian language and culture, which is also an important part of its toolkit elsewhere in the region. Cultural conferences or holiday celebrations are straightforward public-facing events that allow the Embassy or Rossotrudnichestvo to engage in public diplomacy, while partnering with a local organization as co-host.

However, in other respects, the Kremlin’s approach somewhat diverged from the playbook it used in other countries. The absence of religious programming was previously mentioned. In addition, there was less of an emphasis on promoting a narrative of shared Albanian-Russian history. The one exception to this rule were ceremonies celebrating the veterans of WWII and the countries’ common fight against the Axis powers, even though the Soviet support to Hoxha’s guerilla force was limited in scope. [31]

In terms of key target audiences, veterans were a revealed priority, as it was the focus of nearly one-third of Albanian recipient organizations. Beyond this, the Kremlin supported three Albanian organizations focused on the general public, two organizations focused on engaging with Russian compatriots in Albania, and two organizations oriented towards Albanian youth (the Pushkin Albanian Youth Forum and the Organization for the Support of Albania’s Abandoned Children). Youth education is an emphasis of the Kremlin’s overtures elsewhere in the region, but the content was less controversial in Albania, focusing on poetry discussions and orphan support, rather than the mock political roundtables or military-patriotic schools sponsored in countries such as Belarus, Moldova, and Serbia.

3.2 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

Two state-owned media outlets, the Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News, referenced Albanian civic actors 30 times from January 2015 to March 2021. Approximately two-thirds of these mentions (19 instances) were of domestic actors, while the remaining third (11 instances) focused on foreign and intergovernmental actors operating in Albania’s civic space. Russian state media covered a variety of civic actors, mentioning 8 organizations by name and 5 informal groups. In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of Albanian citizens, we also analyzed 36 mentions of five keywords in conjunction with Albania: North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO, the United States, the European Union, democracy, and the West. In this section, we examine Russian state media coverage of domestic and external civic space actors, how this has evolved over time), and the portrayal of democratic institutions and Western powers to Albanian audiences.

3.2.1 Russian State Media’s Characterization of Domestic Albanian Civic Space Actors

Roughly half (53 percent) of Russian media mentions of domestic actors in Albania’s civic space referred to specific groups by name (Table 5). The 4 named domestic actors included three media outlets—Albanian Daily News (3 mentions), Top Channel (3 mentions), and Balkan Insight (2 mentions)—and a political party, the Socialist Movement for Integration (LSI) (2 mentions). Russian state media mentions of these Albanian civic space actors were neutral (100 percent) in tone and generally discussed in the context of reporting news events rather than in-depth analysis. All recorded mentions of domestic media outlets were citations, such as “according to Albanian Daily News.” The two neutral mentions of the LSI were in conjunction with the presidential election in April 2017, when LSI leader Ilir Meta was elected president.

Aside from these named organizations, TASS and Sputnik made 9 generalized mentions of 3 informal groups: Albanian opposition activists, local media, and political parties during the same period. The majority of this coverage was neutral (78 percent); however, Russian media used “somewhat negative” phrases such as “refused to take part in the election” and “claiming the upcoming election was rigged” in relation to boycotts of the April 2017 presidential elections by opposition activists.

Overall, the relatively low number (19) and predominantly neutral tone of mentions of Albanian civic actors over a five-year period could indicate limited interest on the Kremlin’s part to use this channel to influence civic space events in the country. Nevertheless, this relative inattention to civic space matters within Albania is a contrast to negative coverage of Albanian organizations by Russian state media in the context of other Balkan countries, including Kosovo, Serbia, and North Macedonia. This raises a further question, which could merit future study to answer, as to whether the Kremlin instead seeks to minimize mentions of Albania out of a desire to avoid giving the country additional airtime.

Table 5. Most-Mentioned Domestic Civic Space Actors in Albania by Sentiment

|

Domestic Civic Actor |

Neutral |

Somewhat Negative |

Grand Total |

|

Local Media |

5 |

0 |

5 |

|

Albanian Daily News |

3 |

0 |

3 |

|

Top Channel |

3 |

0 |

3 |

|

Opposition |

0 |

2 |

2 |

|

Socialist Movement for Integration (LSI) |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

Balkan Insight |

2 |

0 |

2 |

3.2.2 Russian State Media’s Characterization of External Actors in Albanian Civic Space

Russian state media dedicated the remaining mentions (11 instances) to external actors operating in Albania’s civic space (Table 6). TASS and Sputnik mentioned by name the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (1 mention), along with foreign organizations including Daily Sabah (2 mentions), International Association of Prosecutors (2 mentions), and Express Newspaper (1 mention). Russian state media also mentioned 2 general foreign actors: unnamed Albanian opposition groups in North Macedonia (3 mentions) and foreign journalists (2 mentions).

Russian state media mentions of external actors, both named and unnamed, were generally neutral (82 percent) in tone. There was one important exception: “Albanian minority opposition groups” attracted somewhat negative coverage. Sputnik articles in 2015 accused the organizations of seeking to form Greater Albania and warned of an imminent Balkan crisis sparked by Albanian extremism in North Macedonia. [32] The negative coverage accorded to Albanian diaspora groups highlights a broader theme pursued by Russian state media of presenting ethnic Albanians as a threat to other countries. Yet, intriguingly, the Kremlin does not appear to extend this same treatment to Albanian organizations operating domestically within Albania.

Table 6. Most-Mentioned External Civic Space Actors in Albania by Sentiment

|

External Civic Actor |

Neutral |

Somewhat Negative |

Grand Total |

|

Albanian Opposition Groups in Macedonia |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

Daily Sabah |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

International Association of Prosecutors (IAP) |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

Foreign Journalists |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) |

1 |

0 |

1 |

3.2.3 Russian State Media’s Focus on Albania’s Civic Space over Time

The preponderance of media mentions (93 percent) related to Albania’s civic space centered around two events—the April 2017 presidential elections and a November 2019 earthquake—both of which attracted neutral coverage by Russian state media (Figure 17). More broadly, Russian state media coverage of civic space in Albania is relatively meager compared to the attention the Kremlin pays to other countries in the Eastern Europe and Eurasia region. Noticeably, Russian media ignored several major events occurring within the country during the period of interest. Comparatively, the Kremlin appears to be far more interested in propagating a narrative that Albanian diaspora organizations operating outside of the country in places such as Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Serbia, are dangerous or extremist. In sum, Russia appears to be disengaged from Albania's domestic civic space on the one-hand, while promoting anti-Albanian sentiment in other Balkan countries through its state-run media.

Figure 17. Russian State Media Mentions of Albanian Civic Space Actors

Number of Mentions Recorded

3.2.4 Russian State Media Coverage of Western Institutions and Democratic Norms

In an effort to understand how Russian state media may seek to undermine democratic norms or rival powers in the eyes of Albanian citizens, we analyzed the frequency and sentiment of coverage related to five keywords in conjunction with Albania. [33] Russian News Agency (TASS) and Sputnik News referenced all five keywords from January 2015 to March 2021 (Table 7). Russian state media mentioned the European Union (11 instances), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) (9 instances), the United States (9 instances), the “West” (6 instances), and democracy (1 instance) with reference to Albania during this period. Over half of these mentions (61 percent) were negative.

Table 7. Breakdown of Sentiment of Keyword Mentions by Russian State-Owned Media

|

Keyword |

Extremely negative |

Somewhat negative |

Neutral |

Grand Total |

|

NATO |

3 |

2 |

4 |

9 |

|

European Union |

2 |

3 |

6 |

11 |

|

United States |

4 |

3 |

2 |

9 |

|

Democracy |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

West |

5 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

Russian state media mentioned the European Union most frequently in reference to Albania. Forty-five percent of these mentions were neutral, particularly in regard to Albania’s EU candidacy or sanctions against Russia. In the remaining coverage, the Kremlin was decidedly more negative towards the EU in stories related to Macedonian politics and tensions surrounding ethnic Albanians in the neighboring country, with Russian state media warning that the EU was enabling “the Albanization of the Balkans.” [34] Russian state media also sought to blame the EU for coordinating the expulsion of two Russian diplomats from Albania in response to the poisoning of ex-spy Sergei Skripal in the UK.

The United States received overwhelmingly negative coverage (78 percent), related to tensions in Macedonia that included ethnic Albanians and support of Albania’s accession to NATO. Similarly, Russian state media almost always used the term “the West” negatively in the context of perceived meddling and interference in the region. For example, a 2018 article discussing Albania’s 2017 parliamentary elections quoted the Russian Foreign Ministry as saying, “We underline that unlike some Western countries, Russia is committed to the principle of non-interference in domestic affairs of other countries, including Albania.” [35] By using state media to project a narrative of Western interference in Albania, Russia may seek to draw attention away from its own attempts to exert influence.

NATO attracted negative coverage (55 percent) from Russian state media, often related to the NATO air base built in Albania in 2018. A handful of neutral mentions, discussing Albania’s own contributions to NATO, were included in the Russian state media coverage. The term “democracy” received just one neutral mention, related to ethnic Albanians in Macedonia and the promotion of political discourse. Democracy perhaps was mentioned less by Russian state media in coverage of Albania because the country is viewed as already being closer to the West.

In sum, Russian state media fails to report on many major civil society events in Albania but makes a major effort to highlight the Kremlin’s preferred narratives of Western imperialism and portraying the EU and the U.S. as abetting Albanian diaspora organizations to undermine other countries in the region.

4. Conclusion

The data and analysis in this report reinforces a sobering truth: Russia’s appetite for exerting malign foreign influence abroad is not limited to Ukraine, and its civilian influence tactics are already observable in Albania and elsewhere across the E&E region. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see clearly how the Kremlin invested its media, money, and in-kind support to promote pro-Russian sentiment within Albania and discredit voices wary of its regional ambitions.

The Kremlin deployed multiple tools of influence to amplify the appeal of closer integration with Russia, raise doubts about the motives of the U.S., EU, and NATO, as well as legitimize its actions as necessary to protect the region’s security from the disruptive forces of democracy. It used its cultural and language programming to bolster ties with youth, veterans, and Russian compatriots. In parallel, Russian state media made a substantial effort to portray Albanian minority opposition groups operating in North Macedonia as extremist and Western actors as meddlers enabling the “Albanization of the Balkans.”

Taken together, it is more critical than ever to have better information at our fingertips to monitor the health of civic space across countries and over time, reinforce sources of societal resilience, and mitigate risks from autocratizing governments at home and malign influence from abroad. We hope that the country reports, regional synthesis, and supporting dataset of civic space indicators produced by this multi-year project is a foundation for future efforts to build upon and incrementally close this critical evidence gap.

5. Annex — Data and Methods in Brief

In this section, we provide a brief overview of the data and methods used in the creation of this country report and the underlying data collection upon which these insights are based. More in-depth information on the data sources, coding, and classification processes for these indicators is available in our full technical methodology available on aiddata.org.

5.1 Restrictions of Civic Space Actors

AidData collected and classified unstructured information on instances of harassment or violence, restrictive legislation, and state-backed legal cases from two primary sources: (i) CIVICUS Monitor Civic Space Developments for Albania; and (ii) Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. AidData supplemented this data with country-specific information sources from media associations and civil society organizations who report on such restrictions.

Restrictions that took place prior to January 1, 2017 or after March 31, 2021 were excluded from data collection. It should be noted that there may be delays in reporting of civic space restrictions. More information on the coding and classification process is available in the full technical methodology documentation.

5.2 Citizen Perceptions of Civic Space

Survey data on citizen perceptions of civic space were collected from three sources: the Joint European Values Study and World Values Survey Wave 2017-2021, the Gallup World Poll (2010-2021), and the Balkan Barometer for 2016 and 2018. These surveys capture information across a wide range of social and political indicators. The coverage of the three surveys and the exact questions asked in each country vary slightly, but the overall quality and comparability of the datasets remains high.

The fieldwork for WVS Wave 7 in Albania was conducted in Albanian and English between February and June 2018 with a nationally representative sample of 1435 randomly selected adults residing in private homes, regardless of nationality or language. [36] The research team did not provide an estimated error rate for the survey data after applying a weighting variable “computed using the marginal distribution of age, sex, educational attainment, and region. This weight is provided as a standard version for consistency with previous releases.” [37]

The E&E region countries included in the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 dataset, which were harmonized and designed for interoperable analysis, were Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, and Ukraine. Regional means for the question “How interested have you been in politics over the last 2 years?” were first collapsed from “Very interested,” “Somewhat interested,” “Not very interested,” and “Not at all interested” into the two categories: “Interested” and “Not interested.” Averages for the region were then calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen countries.

Regional means for the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 question “Now I’d like you to look at this card. I’m going to read out some different forms of political action that people can take, and I’d like you to tell me, for each one, whether you have actually done any of these things, whether you might do it or would never, under any circumstances, do it: Signing a petition; Joining in boycotts; Attending lawful demonstrations; Joining unofficial strikes” were calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen E&E countries as well.

The membership indicator uses responses to a Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 question which lists several voluntary organizations (e.g., church or religious organization, political party, environmental group, etc.). Respondents to WVS 7 could select whether they were an “Active member,” “Inactive member,” or “Don’t belong.” The EVS 5 survey only recorded a binary indicator of whether the respondent belonged to or did not belong to an organization. For our analysis purposes, we collapsed the “Active member” and “Inactive member” categories into a single “Member” category, with “Don’t belong” coded to “Not member.” The values included in the profile are weighted in accordance with WVS and EVS recommendations. The regional mean values were calculated using the weighted averages from all thirteen countries included in a given survey wave. The values for membership in political parties, humanitarian or charitable organizations, and labor unions are provided without any further calculation, and the “Other community group” cluster was calculated from the mean of membership values in “Art, music or educational organizations,” “Environmental organizations,” “Professional associations,” “Church or other religious organizations,” “Consumer organizations,” “Sport or recreational associations,” “Self-help or mutual aid groups,” and “Other organizations.”

The confidence indicator uses responses to a Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 question which lists several institutions (e.g., church or religious organization, parliament, the courts and the judiciary, the civil service, etc.). Respondents to the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 surveys could select how much confidence they had in each institution from the following choices: “A great deal,” “Quite a lot,” “Not very much,” or “None at all.” The “A great deal” and “Quite a lot” options were collapsed into a binary “Confident” indicator, while “Not very much” and “None at all” options were collapsed into a “Not confident” indicator. [38]

The fieldwork for the Balkan Barometer 2016 Survey in Albania was conducted in Albanian with a nationally representative sample of 1000 randomly selected adults residing in private homes, whose usual place of residence is in the country surveyed, and who speak the national languages well enough to respond to the questionnaire. Responses were weighted by demographic factors for both country-specific and regional demographic weights. [39] The research team did not provide an estimated error rate for the survey data.

The fieldwork for the Balkan Barometer 2018 Survey in Albania was conducted in Albanian with a nationally representative sample of 1002 randomly selected adults residing in private homes, whose usual place of residence is in the country surveyed, and who speak the national languages well enough to respond to the questionnaire. Responses were weighted by demographic factors for both country-specific and regional demographic weights. [40] The research team did not provide an estimated error rate for the survey data.

The E&E region countries included in both waves of the Balkan Barometer survey were Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia. Respondents to the question “Have you ever done something that could affect any of the government decisions?” were allowed to choose multiple options from the following options: “Yes, I did, I took part in public debates,” “Yes, I did, I took part in protests,” “Yes, I did, I gave my comments on social networks or elsewhere on the Internet,” “I only discussed about it with friends, acquaintances, I have not publicly declared myself [sic],” “I do not even discuss about it [sic],” and “DK/refuse.” Most respondents selected only one option, however, due to double coding the values in this analysis were calculated by the total number of respondents who selected each option in any combination of responses, and therefore add up to a total percentage slightly greater than 100%. Balkan means were calculated using the regional respondent weights from all six Balkan Barometer countries.

Respondents to the Balkan Barometer 2016 question “What is the main reason you are not actively involved in government decision-making?” were allowed to choose a single response from the following options: “I as an individual cannot influence government decisions,” “I do not want to be publicly exposed,” “I do not care about it at all,” and “DK/refuse.” Balkan means were calculated using the regional respondent weights from all six Balkan Barometer countries. These response options differ from those available in 2018, so the two waves’ values cannot be directly compared for Albania but should be assessed relative to the regional mean.

Respondents to the Balkan Barometer 2018 question “What is the main reason you are not actively involved in government decision-making?” were allowed to choose a single response from the following options: “The government knows best when it comes to citizen interests and I don't need to get involved,” “I vote and elect my representatives in the parliament so why would I do anything more,” “I as an individual cannot influence government decisions,” “I do not want to be publicly exposed,” “I do not trust this government and I don't want to have anything to do with them,” “I do not care about it at all,” and “DK/refuse.” Balkan means were calculated using the regional respondent weights from all six Balkan Barometer countries. These response options differ from those available in 2016, so the two waves’ values cannot be directly compared for Albania but should be assessed relative to the regional mean.

The perceptions of corruption indicator uses responses to a series of Balkan Barometer 2018 questions which asks respondents “To what extent do you agree or not agree that [institution] in your economy is affected by corruption?” for several institutions (e.g., religious organizations, political parties, the military, NGOs, etc.). Respondents to the survey could select whether they “Totally agree,” “Tend to agree,” “Tend to disagree,” “Totally disagree,” or “DK/refuse.” The “Totally agree” and “Tend to agree” responses were collapsed into the binary indicator of “Agree” and the “Tend to disagree” and “Totally disagree” responses were collapsed into the binary indicator of “Disagree.” Balkan means were calculated using the regional respondent weights from all six Balkan Barometer countries.

The Gallup World Poll was conducted annually in each of the E&E region countries from 2010-2021, except for the countries that did not complete fieldwork due to the coronavirus pandemic. Each country sample includes at least 1,000 adults and is stratified by population size and/or geography with clustering via one or more stages of sampling. The data are weighted to be nationally representative.

The Civic Engagement Index is an estimate of citizens’ willingness to support others in their community. It is calculated from positive answers to three questions: “Have you done any of the following in the past month? How about donated money to a charity? How about volunteered your time to an organization? How about helped a stranger or someone you didn’t know who needed help?” The engagement index is then calculated at the individual level, giving 33% to each of the answers that received a positive response. Albania’s country values are then calculated from the weighted average of each of these individual Civic Engagement Index scores.

The regional mean is similarly calculated from the weighted average of each of those Civic Engagement Index scores, taking the average across all 17 E&E countries: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. The regional means for 2020 and 2021 are the exception. Gallup World Poll fieldwork in 2020 was not conducted for Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, and Turkmenistan. Gallup World Poll fieldwork in 2021 was not conducted for Azerbaijan, Belarus, Montenegro, and Turkmenistan.

5.3 Russian Projectized Support to Civic Space Actors or Regulators

AidData collected and classified unstructured information on instances of Russian financing and assistance to civic space identified in articles from the Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones between January 1, 2015 and August 30, 2021. Queries for Factiva Analytics pull together a collection of terms related to mechanisms of support (e.g., grants, joint training), recipient organizations, and concrete links to Russian government or government-backed organizations. In addition to global news, we reviewed a number of sources specific to each of the 17 target countries to broaden our search and, where possible, confirm reports from news sources.

While many instances of Russian support to civic society or institutional development are reported with monetary values, a greater portion of instances only identified support provided in-kind, through modes of cooperation, or through technical assistance (e.g., training, capacity building activities). These were recorded as such without a monetary valuation. More information on the coding and classification process is available in the full technical methodology documentation.

5.4 Russian Media Mentions of Civic Space Actors

AidData developed queries to isolate and classify articles from three Russian state-owned media outlets (TASS, Russia Today, and Sputnik) using the Factiva Global News Monitoring and Search Engine operated by Dow Jones. Articles published prior to January 1, 2015 or after March 31, 2021 were excluded from data collection. These queries identified articles relevant to civic space, from which AidData was able to record mentions of formal or informal civic space actors operating in Albania. It should be noted that there may be delays in reporting of relevant news.

Each identified mention of a civic space actor was assigned a sentiment according to a five-point scale: extremely negative, somewhat negative, neutral, somewhat positive, and extremely positive. More information on the coding and classification process is available in the full technical methodology documentation.

[1] The 17 countries include Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

[2] The specific time period varies by year, country, and indicator, based upon data availability.

[3] This definition includes formal civil society organizations and a broader set of informal civic actors, such as political opposition, media, other community groups (e.g., religious groups, trade unions, rights-based groups), and individual activists or advocates. Given the difficulty to register and operate as official civil society organizations in many countries, this definition allows us to capture and report on a greater diversity of activity that better reflects the environment for civic space. We include all these actors in our indicators, disaggregating results when possible.

[4] Much like with other cases of abuse, assault, and violence against individuals, where victims may fear retribution or embarrassment, we anticipate that this number may understate the true extent of restrictions.

[5] The “other” category comprises protestors who are not explicitly identified as part of a political or civic group. In Albania, this includes university students, oil refinery workers and artists.

[6] These tags are deliberately defined narrowly such that they likely understate, rather than overstate, selective targeting of individuals or organizations by virtue of their ideology. Exclusion of an individual or organization from these classifications should not be taken to mean that they hold views that are counter to these positions (i.e., anti-democracy, anti-Western, pro-Kremlin).

[7] A target organization or individual was only tagged as pro-democratic if they were a member of the political opposition (i.e., thus actively promoting electoral competition) and/or explicitly involved in advancing electoral democracy, narrowly defined.

[8] A tag of pro-Western was applied only when there was a clear and publicly identifiable linkage with the West by virtue of funding or political views that supported EU integration, for example.

[9] The anti-Kremlin tag is only applied in instances where there is a clear connection to opposing actions of the Russian government writ large or involving an organization that explicitly positioned itself as anti-Kremlin in ideology.

[10] In collecting this data, we found a report referring to 35 defamation lawsuits filed by PM Rama and officials of the Socialist Party, against political opposition, journalists, and civil society activists. However, the individual cases were not documented and so do not appear in our event-level dataset.

[11] Note that the WVS wave here and throughout the profile refers to the Joint European Values Study and World Values Survey Wave 2017–2021 (EVS/WVS Wave 2017–2021) which is the most recent wave of WVS data. For more information, see Section 5.

[12] Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Tajikistan, Ukraine.

[13] It should be noted that the 2018 Balkan Barometer and the joint European Values Study and World Values Survey Wave 2017–2021 used slightly different questions to gauge whether respondents joined a protest or a demonstration. In this respect, the difference in percentage of respondents reporting that they had participated in protests versus demonstrations might be partly attributable to how respondents understood the question. That said, the observed difference in Albania between the two surveys (0.7 percent) is lower than in other countries.

[14] Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia.

[15] The 2018 Balkan Barometer survey restructured response options to break apathy into additional categories, with two new options, “I do not trust this government” and “I vote for parliament so why do more”, together gaining the respondent share that “I do not care…” lost between the two rounds, although the complete mapping between those survey options is unclear.

[16] The GWP Civic Engagement Index is calculated at an individual level, with 33% given for each of three civic-related activities (Have you” Donated money to charity? Volunteered your time to an organization in the past month? Helped a stranger or someone you didn't know in the past month?) that received a “yes” answer. The country score is then determined by calculating the weighted average of these individual Civic Engagement Index scores.

[17] Charity correlates with GDP (constant Albanian Lek) at 0.827**, p = 0.004.