Beijing’s Big Bet on the Philippines:

Decoding two decades of China’s financing for development

By Samantha Custer, Bryan Burgess, Jonathan A. Solis, Narayani Sritharan, and Divya Mathew

June 2024

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by Samantha Custer, Bryan Burgess, Jonathan A. Solis, Narayani Sritharan, and Divya Mathew (AidData, William & Mary). John Custer and Sarina Patterson supported this publication’s layout, editing, and visuals. Cover by Sarina Patterson, with photos by Rodel Bontes licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 (left) and Toto Lozano, Presidential Communications Operations Office, Philippines, used in the public domain (right). This study was conducted by AidData, a U.S.-based research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute, in collaboration with Asia Society Philippines. We thank Marco A.L.V. Sardillo III, Sarah Gellor-Hidalgo, Timothy Joseph G. Henares, Angela Belonia, and Josephine Andrea M. Dela Cruz for their helpful review and feedback, which strengthened the analysis and findings of this report. We also owe a debt of gratitude to research assistants Diane Frangulea and Kate Kliment, who provided invaluable support in collecting the underlying data for this report. This research was made possible with generous support from the United States Department of State. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

Citation

Custer, S., Burgess, B., Solis, J. A., Sritharan, N. and D. Mathew. (2024). Beijing’s Big Bet on the Philippines: Decoding two decades of China’s financing for development. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary.

Table 2.3: Top 10 sectors for PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines, 2000-2022 10

Figure 2.5: PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines, 2000-2022 13

Figure 2.6: PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines over time, 2000-2022 17

Figures 2.7a and 2.7b: PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines by region, 2000-2021 20

Table 2.8: PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines by region, 2000-2021 21

Figure 2.9: Annual inbound Chinese FDI versus global FDI to the Philippines, 2010-2023 24

Figure 2.10: Annual inbound Chinese FDI as share of total FDI in the Philippines, 2010-2023 25

Figure 2.11: Critical natural resources and inbound Chinese FDI in the Philippines, 2010-2023 27

Table 2.12: Inbound Chinese FDI versus total FDI by sector in the Philippines, 2010-2023 29

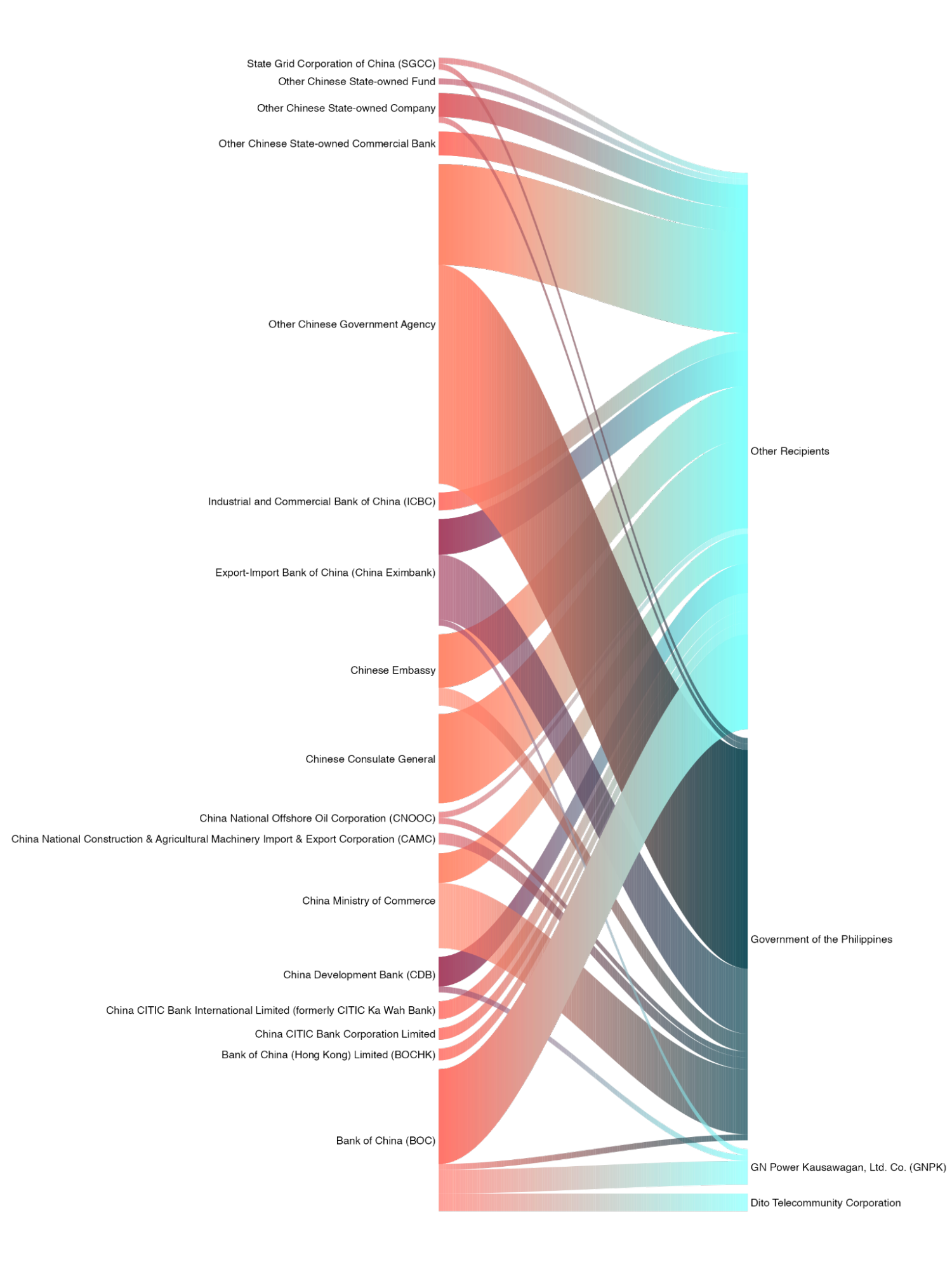

Figure 3.3: Top PRC financiers and their recipients in the Philippines, 2000-2022 35

Figure 3.4: Top 22 co-financiers of PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines, 2000-2021 37

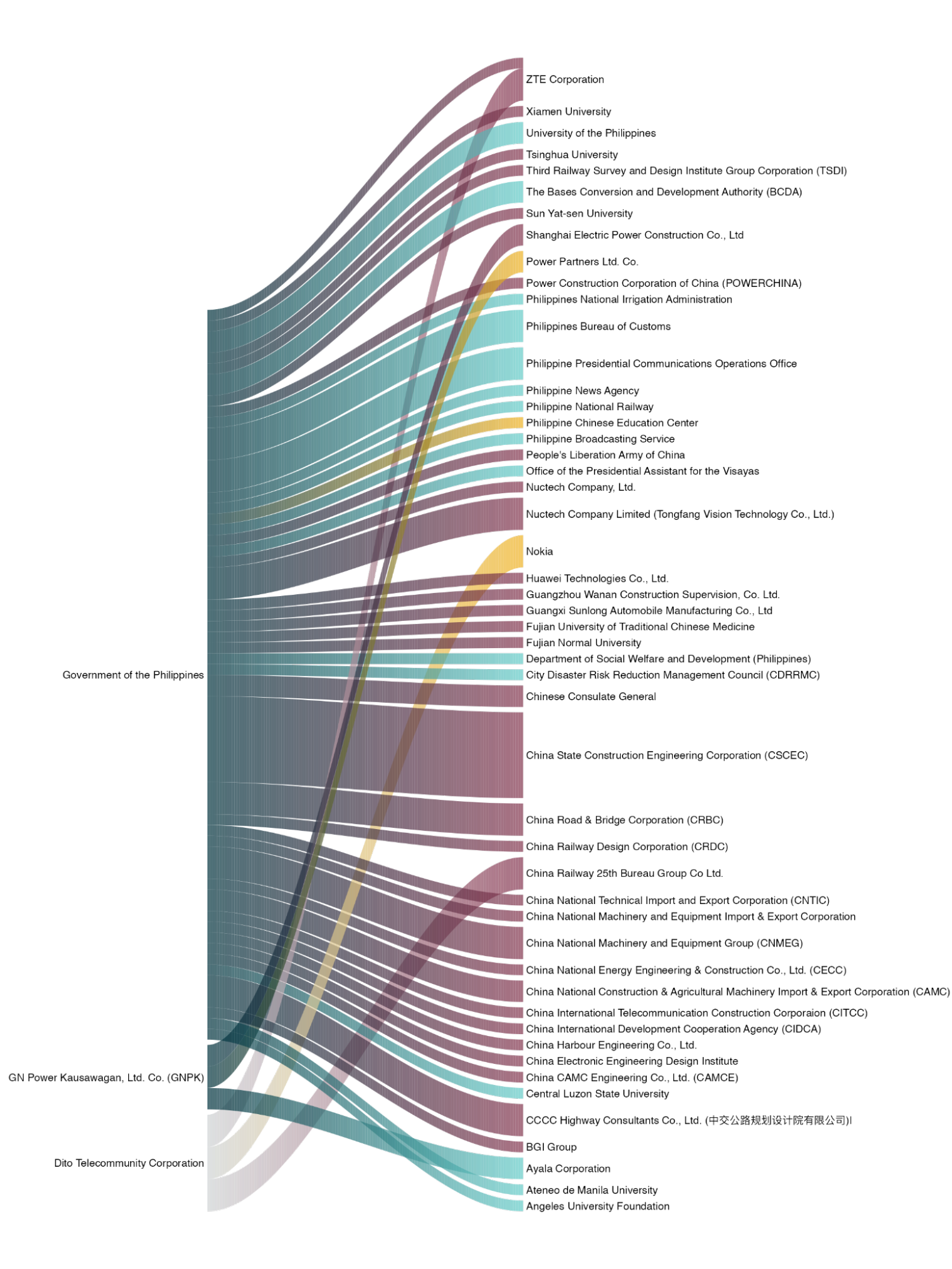

Figure 3.5: Top 20 implementers of PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines, 2000-2021 39

Table 3.9: Philippine recipients of PRC funding by sector, 2000-2022 53

Table 3.10: Recipients of PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines, 2000-2022 54

Table 3.12: Top 15 recipients of PRC funding in the Philippines by dollar value, 2000-2022 57

Table 3.13: Top 15 recipients of PRC funding in the Philippines by project count, 2000-2022 58

Table 4.4: Suspended or canceled Chinese investments in the Philippines, 2000-2021 69

Table 4.7: ESG risks in PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines by sector, 2000-2021 75

Table 4.13: PRC development finance, Chinese FDI, and local economic outcomes, 2014-2023 87

Figure 4.15: Filipino attitudes towards democracy, 2002-2021 91

Executive Summary

In this report, we assess the money, relationships, and outcomes of two decades of Beijing’s financing for development in the Philippines. We aim to answer three critical questions.

- What projects does the People’s Republic of China (PRC) finance, where, and when via its state-directed development finance and private sector foreign direct investment (FDI)?

- How many players are involved in these projects, who are they, what roles do they play, and are some more important than others?

- To what extent does Beijing follow through on its commitments, how does it manage risk, and what are the downstream outcomes?

Following the Money

Beijing has channeled a formidable US$9.1 billion in state-directed development finance to the Philippines over two decades (2000-2022) for more than 200 projects. However, the PRC’s appetite to finance Philippine development is erratic and influenced by its relations with Manila. Beijing bankrolled the Arroyo and Duterte administrations’ priorities with gusto, while frosty relations with Aquino dampened collaboration. As the Marcos Jr administration diversifies its relationships and distances itself from Beijing, future PRC investments will likely mirror dynamics observed previously under Aquino.

The PRC’s support was often smaller (until 2016) and less generous compared with other donors. Moreover, its financing came at a higher cost: only 6 percent was issued as aid (i.e., grants or no- or low-interest loans), and the rest was high-interest debt. Even at the apex of diplomatic relations between the two countries, for every US$1 of aid Beijing gave to the Philippines in 2016, it issued US$167 in debt. By 2019, the terms were worse: US$1 of aid for every US$211 of debt.

Notably, Beijing employs a two-track model in the Philippines. It counts on infrequent big-ticket infrastructure projects, financed with debt on less concessional terms, to generate economic returns. The PRC also subsidizes many inexpensive social projects more frequently to cultivate goodwill.

Beijing uses its development finance to crowd in market opportunities for Chinese firms and bankroll activities in politically important regions. Between 2010 and 2023, new commitments of inbound Chinese FDI to the Philippines (worth US$21.9 billion) skyrocketed by 514 percent, driven by outsized investments in 2012 and 2018. The timing, sector, and geographic focus of these FDI flows reflect the importance of three strategic factors: proximity to PRC development finance projects, the presence of attractive local tax incentives, and Beijing’s desire to position itself as a supplier of value-added products over raw material commodities.

Understanding the Relationships

It is tempting to assume that the PRC operates as a unitary actor with tightly controlled operations among a few players. In fact, our analysis shows the opposite. Fifty-two Chinese financiers, often state-owned policy or commercial banks, were primarily responsible for mobilizing money. However, Beijing relies on an extensive network of 101 banks from across Europe, North America, and Asia as co-financiers to pool risk, vet borrowers, assess project viability, and contribute capital for big-ticket infrastructure projects.

Beijing has an overreliance on 37 Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) as its go-to implementers. Opaque assistance terms, limited competitive procurement, and weak reporting requirements create perverse incentives for these implementers to cut corners or collude with local counterparts. Notably, 43 percent of Chinese SOE implementers in the Philippines have been directly sanctioned by international finance institutions like the World Bank or Asian Development Bank for questionable financial practices or indirectly associated with such practices through a parent-subsidiary relationship.

On the demand side, local governments in economically dynamic and politically connected areas and national-level agencies were frequent recipients of PRC-financed projects. State-owned and private sector firms in the energy, utilities, and extractives sectors attracted sizable dollars. Beijing is favorably disposed to work with recipients that have strong ties to mainland China (promoting Chinese language and culture) or linkages via Filipino-Chinese diaspora families or groups.

Unpacking the Outcomes

Although Beijing delivers on projects more quickly in the Philippines—just under one year on average from committing financing to completing a project—some regions and sectors have longer wait times than others. Big-ticket infrastructure projects are more risky and complex to execute. For example, the worst delays were in the agriculture, forestry, and fishing sectors where projects took more than four years to deliver, reflecting logistical hurdles, environmental challenges, or social unrest from displacement.

Although the particulars of the six suspended or canceled PRC projects varied, common themes emerged: weak management and oversight systems in the Northrail and National Broadband Network projects; local opposition to project goals and financing in the Agus 3 Hydropower and Cyber Education projects; external shocks such as COVID-19 prompting China to exit from the Panay-Guimaras-Negros Island Bridges project; and geopolitical sensitivities stoking calls to cancel contracts with the PRC over maritime disputes.

Taking a portfolio-level view, Beijing’s development finance faces heightened exposure to risk from its trusted cadre of Chinese state-owned and private sector implementers. Over half of the PRC’s development finance dollars (US$4.5 billion) relied on Chinese implementers with tarnished performance. Six of the highest-risk firms, involved in US$870 million worth of PRC-financed development projects, were associated with both questionable financial practices and higher ESG risk exposure.

What are the outcomes of Beijing’s infrastructure bonanza in the Philippines? Chinese financing (both development finance and FDI) may positively contribute to economic gains, at least in aggregate terms. However, these benefits do not yet appear to trickle down in a visible way to Filipinos. As PRC financing increased, Filipinos surveyed were more likely to say they struggled to afford food and shelter, an important indicator of financial health.

Just under 40 percent of Beijing’s development finance portfolio in the Philippines is associated with at least one type of environmental (E), social (S), or governance (G) risk. However, there is less clarity on whether and how these risks translate into measurable harm. PRC development finance and FDI were associated with favorable outcomes in the social sector (i.e., youth development and civic engagement). Results were polarized when it came to governance and environmental outcomes.

1. Introduction

When Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo took office in 2001, economic engagement with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was modest. Bilateral trade between the two nations at the time amounted to a little over US$3.0 billion, concentrated on Philippine exports of integrated circuits to Chinese companies (OEC, 2022). China was not yet importing nickel at any scale. Nor was Beijing bankrolling big-ticket investments in infrastructure and critical industries that would become the backbone of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The Philippine-PRC relationship is decidedly different today. Beijing has become a go-to source of development finance and foreign direct investment (FDI). Over roughly two decades (2000-2022), the Philippines attracted US$9.1 billion in PRC financing for more than 200 development projects. These activities involved a staggering number of players: financiers or implementers from China, the Philippines, and 22 other countries and territories. Additionally, Chinese FDI during this time was worth another US$21.9 billion in financing inbound to the Philippines.

High-risk, high-reward infrastructure investments attracted the lion’s share of the PRC’s development finance and Chinese FDI dollars. Beijing also bankrolled small-dollar social and educational projects to build goodwill. Taken together, these projects have the potential to transform local economies, ecosystems, governance norms, and social rhythms—for better or worse. Although some of Beijing’s efforts have made laudable contributions to Philippine growth and prosperity, others have failed to materialize, struggled during implementation, or triggered debate over their outcomes.

Launched with great fanfare and ample controversy, there is surprisingly little hard evidence for the Philippine public to assess the true costs and benefits of partnering with Beijing. This report arrives at a critical inflection point as the Philippines is considering a reset in its relationship with the PRC. On the heels of President Duterte’s enthusiastic embrace of Beijing, relations between the two countries have since become strained in the early days of President Marcos Jr’s administration. The Philippines withdrew from three BRI railway projects in November 2023. Chinese Coast Guard vessels shot water cannons at a Philippine patrol boat on the Second Thomas Shoal in March 2024 amid unresolved maritime disputes between the two countries. Meanwhile, Marcos Jr has courted infrastructure financing from the United States (McCartney, 2023; Widakauswara, 2024).

In this report, Beijing’s Big Bet on the Philippines, we meticulously piece together data from multiple sources to assess the money, relationships, and outcomes from two decades of PRC investment. Chapter 2 follows the money to spotlight Beijing’s revealed priorities in what projects it finances, where, and when in the Philippines. Chapter 3 scrutinizes the relationships behind these investments: how many players, who are they, what roles do they play, and are some more important than others? Chapter 4 assesses Beijing’s performance—to what extent does it follow through on its commitments, how does it manage the risk of public harm from its projects, and what early indications do we see of the downstream outcomes across society? Chapter 5 concludes with key takeaways arising from this research.

2. Money

Key insights in this chapter:

- Beijing’s development finance has grown over two decades, but support fluctuates across administrations and is smaller and less generous than many donors

- Beijing employs a two-track model in the Philippines—it offsets a few risky hard infrastructure big bets with many small-dollar social development projects

- The energy and metals sectors showcase how Beijing’s state-directed development and private-sector FDI reinforce each other to advance shared goals

The last four Philippine presidents—Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, Benigno Aquino III, Rodrigo Duterte, and Ferdinand Marcos Jr—have held dramatically different stances toward the PRC. So too has Beijing’s appetite to finance the Philippines’ growth and development varied substantially over this period. When a president’s rhetoric and policy signaled openness to Beijing, PRC officials were opportunistic about bankrolling their counterparts’ priorities with great fanfare. Conversely, when a more adversarial administration takes power, the dollar value and number of PRC-financed development projects in the Philippines tend to plummet.

In this chapter, we follow the money to highlight Beijing’s revealed priorities in what projects it finances, where, and when in the Philippines. Using two decades of historical data, we have a unique opportunity in this report to examine these dynamics more closely. Our analysis investigates how PRC development finance and inbound Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) have changed over time in absolute terms relative to the alternatives. We surface insights about which sectors and communities attract more or less PRC development projects and investment dollars—and why.

By development finance, we refer to how the PRC employs state-directed grants, loans, other debt instruments, and in-kind and technical assistance to support the Philippines. This development finance includes Official Development Assistance (i.e., grants and no- or low-interest loans, typically referred to as “aid”) and Other Official Flows (i.e., loans and other debt instruments approaching market rates, referred to as “debt”). We also consider inbound Chinese FDI, which involves investors establishing a lasting interest in, and a significant degree of influence over, an enterprise resident in the Philippines, defined by an ownership stake of 10 percent or more (OECD, n.d.a and n.d.b).

For this analysis, we draw upon three primary sources: (i) AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0, a project-level database of Chinese state-directed aid and debt financing from 2000-2021; (ii) supplemental desk research to identify provisional projects for 2022;[1] and (iii) inbound Chinese FDI data tracked by the global fDi Markets online database of cross-border greenfield investments for the Philippines, produced by Financial Times, Ltd.[2]

2.1 How has the PRC’s development finance changed over time in absolute terms and relative to the alternatives?

From a slow start, Beijing’s development finance has skyrocketed over the last 20 years. However, the PRC’s assistance does not operate in a vacuum. There are a host of other bilateral and multilateral development partners actively supporting development in the Philippines. This raises a critical question: how does Beijing’s contribution compare to the alternatives when it comes to the volume, focus, and terms of its assistance? In this section, we take a closer look at variations in PRC financing compared with other development partners (Section 2.1.1), across administrations (Section 2.1.2), and between different subnational regions (Section 2.1.3).

2.1.1 How does Beijing compare with other development partners?

To situate its assistance relative to other development partners, we benchmarked the PRC against six active players in the Philippines: the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Australia, Japan, South Korea, the United States (U.S.), and the World Bank (WB). Each of the six comparators reports their development finance by country, sector, flow type, and year to the OECD’s Creditor Reporting System. Our analysis considers Official Development Assistance (i.e., grants and no- or low-interest loans, commonly referred to as “aid”) and Other Official Flows (i.e., loans and export credits at market rates referred to as “debt”). For comparability, we focus this discussion on commitments.

Between 2000 and 2022, the PRC’s US$9.1 billion in commitments fell in the middle of the pack. Beijing outspent other bilaterals such as Australia (US$2.3 billion), South Korea (US$4.5 billion, and the U.S. (US$4.6 billion) by a considerable margin. Nevertheless, it lagged behind multilaterals such as the ADB (US$23.8 billion) and the World Bank (US$16.3 billion). As the Philippines’ leading bilateral development partner, Japan (US$21.7 billion) was well ahead of the field for most of the two-decade period.

However, this is an “apples and dragon fruits” comparison (Dreher et al., 2018). The cost to the Philippines to access financing from its two largest bilateral donors is quite different. Tokyo offers more generous terms: 98 percent of its financing was in the form of grants and no- or low-interest loans (Table 2.1). Only 6 percent of Beijing’s financing was offered on similarly generous terms. The PRC relies heavily on higher-interest loans and other debt instruments. On the surface, it has a similar ratio of aid to debt as the two multilaterals. However, there is another important difference here—the level of concessionality. ADB and World Bank loans are still focused on development outcomes and often provided at discounted rates. For example, in a comparison of infrastructure projects under Duterte’s “Build, Build, Build” initiative, Tabbada and Pacho (2022) found that projects financed by the World Bank and the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) offered less onerous interest rates than those offered by the PRC for similar efforts.[3]

Table 2.1: Total official finance commitments from major development partners to the Philippines, 2000-2022

The PRC was initially a relatively small player (Figure 2.2), as most of the Philippines’ development finance commitments between 2000 and 2009 came from another bilateral source: Japan (US$4.8 billion). Multilateral development banks like the World Bank and Asian Development Bank also played an outsized role from 2010 onwards. By contrast, it was not until 2016 that the PRC catapulted ahead of its peers as the top development finance supplier. Yet, the PRC’s assistance fell off thereafter, particularly during the COVID-19 period, in absolute terms and compared to others.[4]

Figure 2.2: Official finance commitments by year from major development partners to the Philippines, 2000-2022

The Philippine Development Plan (2023-2028) outlines several different facets of infrastructure as essential to the nation’s growth and prosperity, such as (i) physical connectivity; (ii) utilities; (iii) social; and (iv) information (NEDA, 2023).[5] Building on this foundation, in this report, we consider the extent to which Beijing (as compared to other development partners) finances these different types of infrastructure, including:

- Economic and information infrastructure (i.e., banking and financial services; business services; telecommunications; economic infrastructure and services)

- Physical connectivity infrastructure (i.e., trade policies and regulations; transport and storage)

- Utilities, food, and power infrastructure (i.e., agriculture, forestry, fishing; energy; industry, mining, construction; production sectors; water supply and sanitation)

- Social and environmental infrastructure (i.e., education; environmental protection; government and civil society; health; social infrastructure and services; population policies/programs; and reproductive health)

Most of Beijing’s development finance over the last two decades has focused on hard infrastructure sectors (i.e., economic and information, physical connectivity, utilities, food, and power). However, it has implemented a large number of small-dollar projects supporting social development in the Philippines (see Table 2.3). The PRC does not invest much in areas such as environmental protection, disaster prevention, and the government and civil society.

Table 2.3: Top 10 sectors for PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines, 2000-2022

| Top 10 sectors by project value | Millions USD | Top 10 sectors by project count | Count |

| 1. Energy | 3,220 | 1. Health | 46 |

| 2. Transport and storage | 1,328 | 2. Emergency response | 44 |

| 3. Communications | 1,001 | 3. Education | 32 |

| 4. Water supply and sanitation | 934 | 4. Agriculture, forestry, fishing | 14 |

| 5. Business and other services | 781 | 5. Transport and storage | 12 |

| 6. Industry, mining, construction | 389 | 6. Communications | 12 |

| 7. Agriculture, forestry, fishing | 387 | 7. Business and other services | 12 |

| 8. Trade policies and regulations | 291 | 8. Energy | 10 |

| 9. Unallocated/unspecified | 261 | 9. Government and civil society | 9 |

| 10. Banking and financial services | 231 | 10. Developmental food aid/food security assistance | 8 |

Like the PRC, Japanese development agencies directed most of their funding to the transport sector, spending a total of US$14.6 billion—nearly US$6 billion more than the other five donors combined (US$8.57 billion). South Korea also has an outsized interest in bankrolling hard infrastructure projects (transport and storage; industry, mining, construction; and energy), albeit with a smaller budget. Seoul is the only external donor mobilizing comparable funds to the PRC in one area: telecommunications (US$753 million to US$1.0 billion, respectively).

But Beijing has been willing to take on infrastructure projects other donors have walked away from. The bridge connecting Davao City to Samal Island, a popular tourist site, is one such example. The Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) conducted a feasibility and environmental impact study in 2016, proposing a landing location on Samal with minimal environmental or real estate impacts (JICA, 2018a; Ledesma, 2020). However, later in 2020, the ADB, backed by a roughly US$350 million Chinese loan, consulted with then Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte to develop a plan to deliver the Samal Island-Davao City Connector (SIDC) bridge as a flagship project for President Duterte’s “Build, Build, Build” Initiative (Pinlac, 2022; Ledesma, 2020).[6]

Other development partners diverged from the PRC’s priority sectors to some extent. The World Bank focused on agriculture, forestry and fishing; government and civil society; social infrastructure and service; energy; and disaster prevention. It was a leading supplier of emergency response support to save lives in the aftermath of earthquakes, typhoons, and volcano eruptions. Meanwhile, the U.S. was the leading donor for food assistance and environmental protection. Both the U.S. and Australia committed large sums to strengthen social infrastructure via investments in education, government, and civil society (Table 2.4).

This positioning is fairly consistent with how Asia-Pacific leaders, including those in the Philippines, view these players’ comparative advantages. In a 2022-2023 survey, Custer et al. (2024) found that public, private, and civil society leaders in the region viewed leading democracies such as the U.S. as preferred partners for governance and social sector projects but looked to Beijing for hard infrastructure and energy projects.

Table 2.4: Total official finance commitments from major development partners to the Philippines by sector, 2000-2022

2.1.2 How has Beijing’s financing changed across administrations?

As an economist by training, President Arroyo was adamant that growth and job creation would drive her foreign policy (Government of the Philippines, 2004; Tran, 2019). She publicly embraced the PRC as a friend, even amid the Philippines’ maritime disputes with China (ibid). In parallel, Jiang Zemin’s “Going Out” (or “Going Global”) policy provided PRC officials with a clear mandate to look outward to put China’s excess industrial capacity to productive use abroad. Beijing’s development finance to the Philippines grew by over 950 percent during Arroyo’s time in office (from US$88 million to US$931 million), particularly in the areas of energy and telecommunications.

Nevertheless, even during a so-called “golden age” of PRC-Philippine relations (PRC Embassy, 2005), Beijing’s bankrolling of development projects was episodic, with notable peaks in 2004, 2006, and 2010, surrounded by lower activity (Figure 2.2). These fluctuations were likely driven, at least in part, by the nature of PRC development finance, which prioritizes a few large-dollar investments that take multiple years to implement alongside many small-dollar education and social development efforts (Figure 2.5).

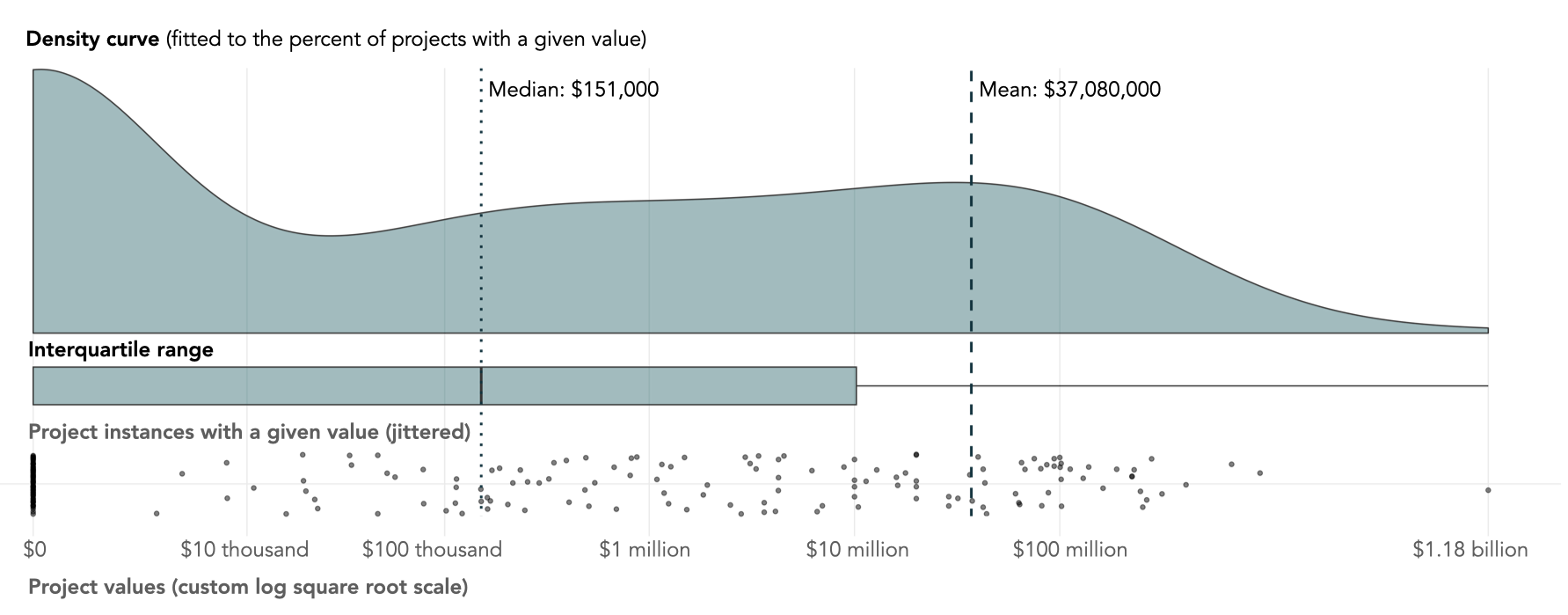

Figure 2.5: PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines, 2000-2022

Notes: This “raincloud” visualization illustrates the

distribution of PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines

according to the financial values associated with the project. Each

black dot along the x-axis represents a PRC-funded development

project. (Note that dots overlap and that not all projects can be

visualized due to space constraints.) The interquartile range, from

nearly $0 to $10 million, represents the upper and lower limits of

the middle half of project values. The density curve represents the

distribution of values in the dataset. For visualization purposes, a

custom scale along the x-axis expands values closer to $0 and

compresses values above $1 million. Sources: AidData’s Global

Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0 for 2000-2021

(Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022). Supplemented by limited

desk research and media article review by the research team to

identify additional projects and details for 2022.

Notes: This “raincloud” visualization illustrates the

distribution of PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines

according to the financial values associated with the project. Each

black dot along the x-axis represents a PRC-funded development

project. (Note that dots overlap and that not all projects can be

visualized due to space constraints.) The interquartile range, from

nearly $0 to $10 million, represents the upper and lower limits of

the middle half of project values. The density curve represents the

distribution of values in the dataset. For visualization purposes, a

custom scale along the x-axis expands values closer to $0 and

compresses values above $1 million. Sources: AidData’s Global

Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0 for 2000-2021

(Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022). Supplemented by limited

desk research and media article review by the research team to

identify additional projects and details for 2022.

The Philippines’ first PRC debt-financed development project beginning in 2001, a US$88 million line of credit for the Department of Finance for an irrigation project in Ilocos Sur province, was a sign of things to come (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022). The project’s emphasis on water supply and power grid expansion served as something akin to a trial run for even larger investments in those two sectors over the next two decades. With the exception of humanitarian aid, the vast majority of PRC project funding during Arroyo’s administration would come via loans with fairly standardized interest rates (3-3.5 percent interest) and maturities (7-12 years).

Ambitions were high: the Banaoang Pump Irrigation Project aimed to expand local rice production and market access through improved roads and electrical connectivity, building a pumping station and a series of irrigation canals (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022). The project was expected to irrigate over 6,000 hectares of land to benefit over 5,000 farming families. However, the implementing partner for the irrigation project, the state-owned China National Construction & Agricultural Machinery Import & Export Corporation (CAMC), quickly ran behind schedule, an indication of CAMC’s relative inexperience at this early stage in delivering overseas projects.

In 2006, Beijing bankrolled 10 projects worth US$204 million dollars, spanning business development and trade expansion, along with emergency response to aid communities impacted by Typhoon Reming and the Southern Leyte landslide. In 2010, Arroyo’s final year in office, PRC investment jumped to a historic high, reaching US$931 million in a single year driven by two projects: a coal-fired power plant in Mariveles, and the treatment of wastewater in Metro Manila (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022). An additional agreement for the expansion of Digital Mobile’s 3G network was signed in September 2010 after Arroyo had left office.

Noteworthy for their size (the largest was worth US$687 million), these projects were also illustrative of a broader trend: the privatization of debt financing for development. Increasingly, the PRC was lending to private sector actors in the Philippines and elsewhere, often with sovereign guarantees that made the host country government accountable if a private company failed to repay (Malik et al., 2021).

Arroyo’s enthusiasm to pursue stronger ties with Beijing was not without criticism. Domestic critics accused the president of corruption, election fraud, and “trading Philippine sovereignty for personal benefits” (Quimpo, 2009; Zha, 2015; Tran, 2019). Under pressure at home, Arroyo suspended a Cyber Education project worth US$466 million, canceled a US$329 million National Broadband Network project, and was compelled to safeguard Philippine maritime boundaries as the PRC began to flex its naval muscles to assert its territorial claims in the South China Sea (West Philippine Sea) (Tran, 2019).

The election of President Aquino in May 2010 marked an inflection point in the PRC-Philippine relationship. Diplomatic relations with Beijing took on a chillier turn. During the first few months of Aquino’s presidency, the PRC expanded its presence in the Spratly Islands and made six incursions into Philippine territorial waters (Thayer, 2014). Heated rhetoric and gamesmanship over conflicting claims in the South China Sea (West Philippine Sea) characterized much of the Philippine-PRC relationship during Aquino’s tenure. Aquino protested the PRC’s claims, initiating arbitral proceedings against Beijing in 2013 under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (PCA, 2013), and meeting with ASEAN peers and the U.S. Coast Guard (Thayer, 2014).[7]

Frosty diplomatic relations extended to declining interest from leaders on both sides to collaborate on new development projects and move forward with past agreements.[8] During the Aquino administration, the Philippines received less money from the PRC over six years and 14 projects than it did from just one of the three projects that Chinese banks funded in 2010, the final year of the Arroyo administration.

There were only three consequential development finance agreements between the two countries during the Aquino era. Two of these agreements were loans issued by PRC state-owned banks to two Philippine firms: the San Miguel Corporation (a business conglomerate working across the food and beverage, energy, and infrastructure industries) and Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation (a privately owned bank) (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022). In both instances, Chinese banks were the primary but not sole lenders, instead working as part of a larger group of 33 and 17 entities, respectively. The third instance was a loan agreement with the Development Bank of the Philippines (a state-owned development bank), where the Bank of China was a mid-sized lender among a group of 20 banks. This arrangement is often referred to as “syndicated lending,” in which a lead bank manages contributions from other lenders (i.e., the syndicate) who jointly provide financing to the same borrower using the same loan terms (BOC, n.d.).

Otherwise, PRC assistance during Aquino’s tenure was limited to smaller-scale goodwill projects oriented more towards stoking positive public opinion than responding to the priorities of political leaders. In this ‘quiet’ phase of PRC-Philippine relations, Beijing was likely cultivating people-to-people ties to create a more conducive environment for a resurgence of cooperation with the next administration, once Aquino stepped out of power.

One such goodwill project was a US$2 million grant from the PRC’s Ministry of Commerce to continue technical cooperation with the Philippines-Sino Center for Agricultural Technology, though notably at a lower level of support than its previous grant to the joint effort in 2003 (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022). Beijing also made modest donations to the National Library of the Philippines and helped establish a Confucius Institute at the University of the Philippines. On a somewhat larger scale, the PRC sent several rounds of emergency aid and a hospital ship to aid victims of Typhoon Yolanda.

Assuming office in mid-2016, President Duterte’s stated aspiration for the Philippines to pursue an “independent” foreign policy, his appreciation for the PRC’s economic power, and Beijing’s willingness to back his anti-drug policies provided a favorable environment for renewed cooperation between the countries (Tran, 2019; Blanchard, 2016). By extension, the Philippines attracted by far the greatest volume of new projects (174) and development finance dollars (US$6.2 billion) during Duterte’s tenure (2016-2022), as compared to his predecessors (Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6: PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines over time, 2000-2022

In record time, Duterte mobilized US$2.2 billion in loans for two power projects in Dinginin and Kauswagan (from July to September 2016). Following his state visit to China (between October and December 2016), Beijing agreed to bankroll 10 additional development projects in the Philippines worth US$28 million. GNPower, through its special purpose vehicles[9] GNPower Dinginin Ltd. Co (GNPD) and GNPower Kauswagan Ltd. Co (GNPK), was looking to secure project funding prior to the election; however, the speed with which these loans were finalized suggests that the PRC was weighing the political situation in their calculus (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022).

The PRC was highly attuned to the priorities of its newfound ally in President Duterte, namely his “Build, Build, Build” program, which aimed to usher in a new “golden age of infrastructure in the Philippines” (DBM, n.d.). The largest PRC-financed projects in the early years of Duterte’s tenure were in hard infrastructure sectors (industry, mining, and construction; energy; and water). Telecommunications also attracted ample attention from PRC financiers during this period, though these investments were more diffused across partners and years. In fact, the top sectors attracting PRC development finance dollars (by project value) for the 2000-2022 period highly converged with the infrastructure priorities of both Duterte and Arroyo.

Beijing’s interest in financing development in the Philippines proved to be fairly durable, as the number of projects increased at a rapid clip throughout Duterte’s presidency—from 14 projects in 2016 to 44 projects in 2021. Although the big-ticket infrastructure projects still tended to attract debt financing (loans approaching market rates and export credits), the year-on-year growth in the number of projects was driven by an uptick in aid activities in the health, education, and emergency response sectors financed on more generous terms (e.g., grants and no- or low-interest loans).[10]

Riding high following a resurgence of inbound PRC development finance in 2016, Philippine officials were publicly optimistic about the prospects of their country joining Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2017. Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III declared that the initiative would bolster the Philippines’ ports and airports (DoF, 2017), and the South China Morning Post promised a “flurry of Chinese-invested projects” destined for Duterte’s hometown of Davao (Huang, 2017).

Instead, new development finance from Beijing decreased in 2017 and 2018, while commitments in 2019 and 2022 were one billion dollars lower than the peak of 2016. As the PRC’s development finance tapered off, the Philippines still mobilized FDI from commercial Chinese enterprises, rather than state-backed banks, in 2018. However, this, too, was relatively unstable and fell off in 2019. Section 2.2 discusses Chinese FDI in the Philippines in greater depth.

Despite warming relations, Beijing did not become more generous to the Philippines in terms of the cost of accessing its financing. For every US$1 of aid that Beijing gave the Philippines in 2016, it issued US$167 of debt. By 2019, the terms were even more unbalanced: US$1 of grant funding for every US$211 of debt. The reason comes down to a common feature in the PRC’s development finance globally: it bankrolls a small number of high-cost hard infrastructure projects from which it expects an economic return, alongside a large number of inexpensive social projects to cultivate goodwill. Although the PRC occasionally has financed infrastructure projects with grants and no- or low-interest loans, these are increasingly the exception rather than the rule.

The decrease in new development finance dollars from Beijing, alongside increasing costs for the Philippines to access this financing, may be less a reflection of bilateral Philippine-PRC relations than a broader repositioning of Beijing’s portfolio. PRC officials, seeing a growing number of BRI countries struggling to service mounting debts from PRC-financed development, began to pivot away from bankrolling ‘new’ infrastructure projects to bailing out the ‘old’ projects through supplying emergency lending (e.g., balance-of-payment loans, currency swaps) to assist its borrowers with limited-term cash liquidity to avoid default (Horn et al., 2023). Moreover, in an attempt to “de-risk its overseas lending portfolio” globally (Parks et al., 2023), the PRC expanded the frequency with which it co-financed projects with commercial banks in other countries to pool risk and mobilize capital.

This global context may shed insight into the rationale behind the PRC’s less generous financing terms in backing the Philippines Clark Global City project. Highly aligned with the stated priorities of Beijing’s Maritime Silk Road Strategy (PRC State Council, 2017), the Philippines sought to expand a mixed-use business district in the Clark Freeport Special Economic Zone adjacent to Clark International Airport (in the city of Mabalacat in Pampanga province). The Bank of China teamed up with two Philippine commercial banks, Banco de Oro and Philippine National Bank, as co-financiers to make a US$265 million syndicated loan commitment to the project. The financing came with a 10-year maturity and a 7.61 and 8.98 percent interest rate (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022). Comparatively, development finance loans offered by Japan (another frequent supplier of loans) are typically more concessional, with interest rates close to 1 percent on average (OECD, 2023), grace periods of 10 years, and repayment periods of 40 years (OECD, 2020).

Two years into the tenure of Duterte’s successor, President Marcos Jr, we can only make educated guesses as to how the PRC’s development finance may evolve. There was a post-COVID-19 pandemic rebound in the dollar value of new PRC projects in 2022 (US$1.06 billion), compared to a slump in 2020 and 2021. Three planned projects account for eighty percent of the estimated new money: the Samal-Davao bridge project in former President Duterte’s hometown; a loan for Manila Water Company to expand its operations; and an investment in the next phase of the Kaliwa Dam project. This debt financing was paired with 11 smaller aid-like activities in the social sector (e.g., education, health, and social services). Some deals could reflect Beijing’s warm relations with Duterte, whose tenure ended mid-2022.

The PRC’s behavior in past election years (e.g., 2010 and 2016) has signaled anticipated relations with an incoming president. Beijing’s naval assertiveness in the early months of Aquino’s presidency was matched with a slowdown in development finance. At the same time, its rapid approval of a few high-value infrastructure projects paired with a larger number of small-scale goodwill social projects was responsive to a perceived thaw in relations with the Philippines in the early months of Duterte’s tenure. As the Marcos Jr administration diversifies its international relationships and distances Manila from Beijing, it is likely that PRC investments will mirror the dynamics observed previously under Aquino.

2.1.3 In which communities is the PRC investing—and why?

In this section, we explore whether and how the PRC’s development finance may vary in another respect: geography. To answer this question, we draw upon the location information in AidData’s project-level data on PRC development finance to identify the subnational distribution of Beijing’s activities within the Philippines across 17 regions (the first administrative division level). Looking at these investments over more than two decades (2000-2021),[11] Beijing was most interested in bankrolling activities in politically important regions, which represent attractive markets for Chinese firms (see maps below).

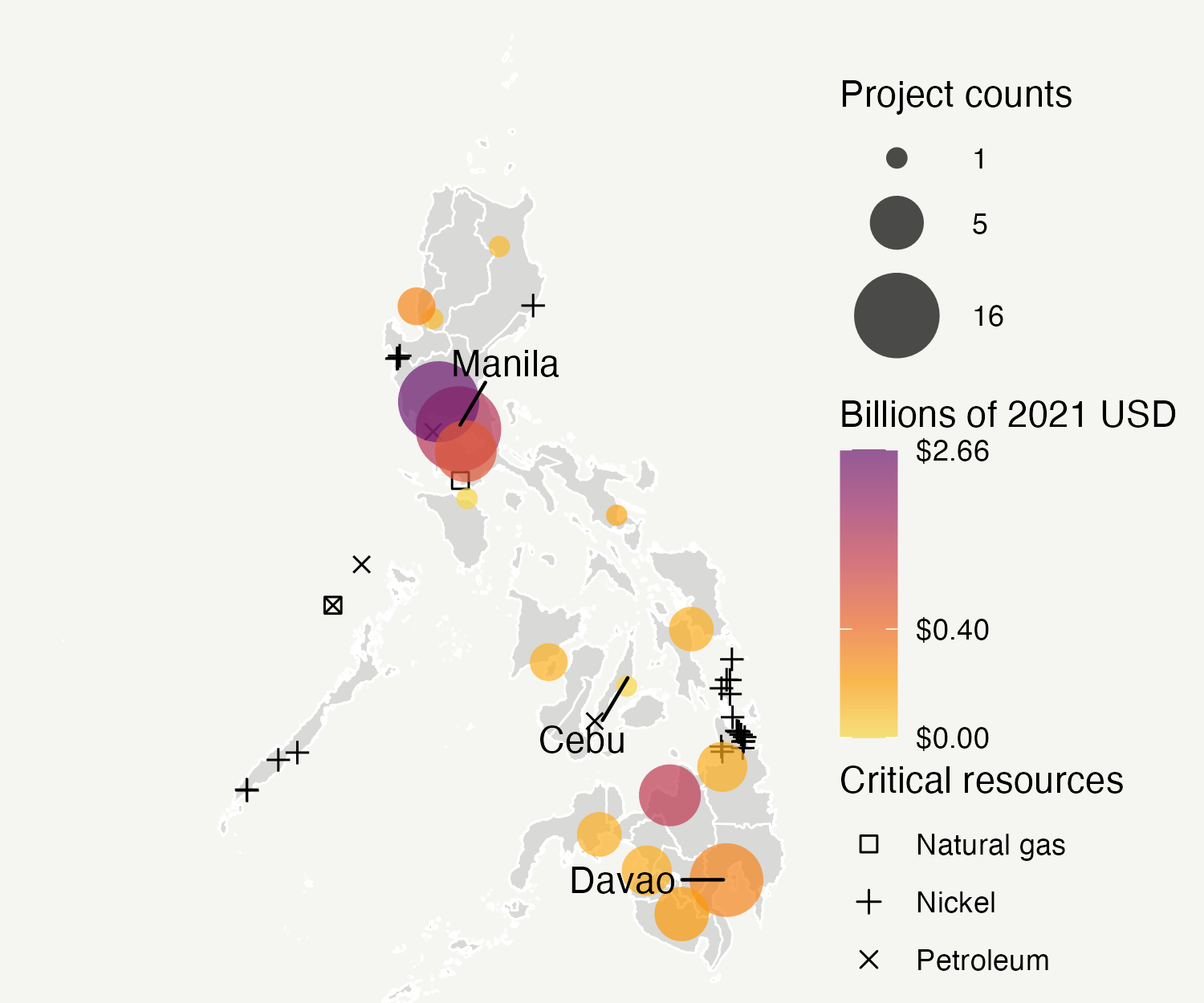

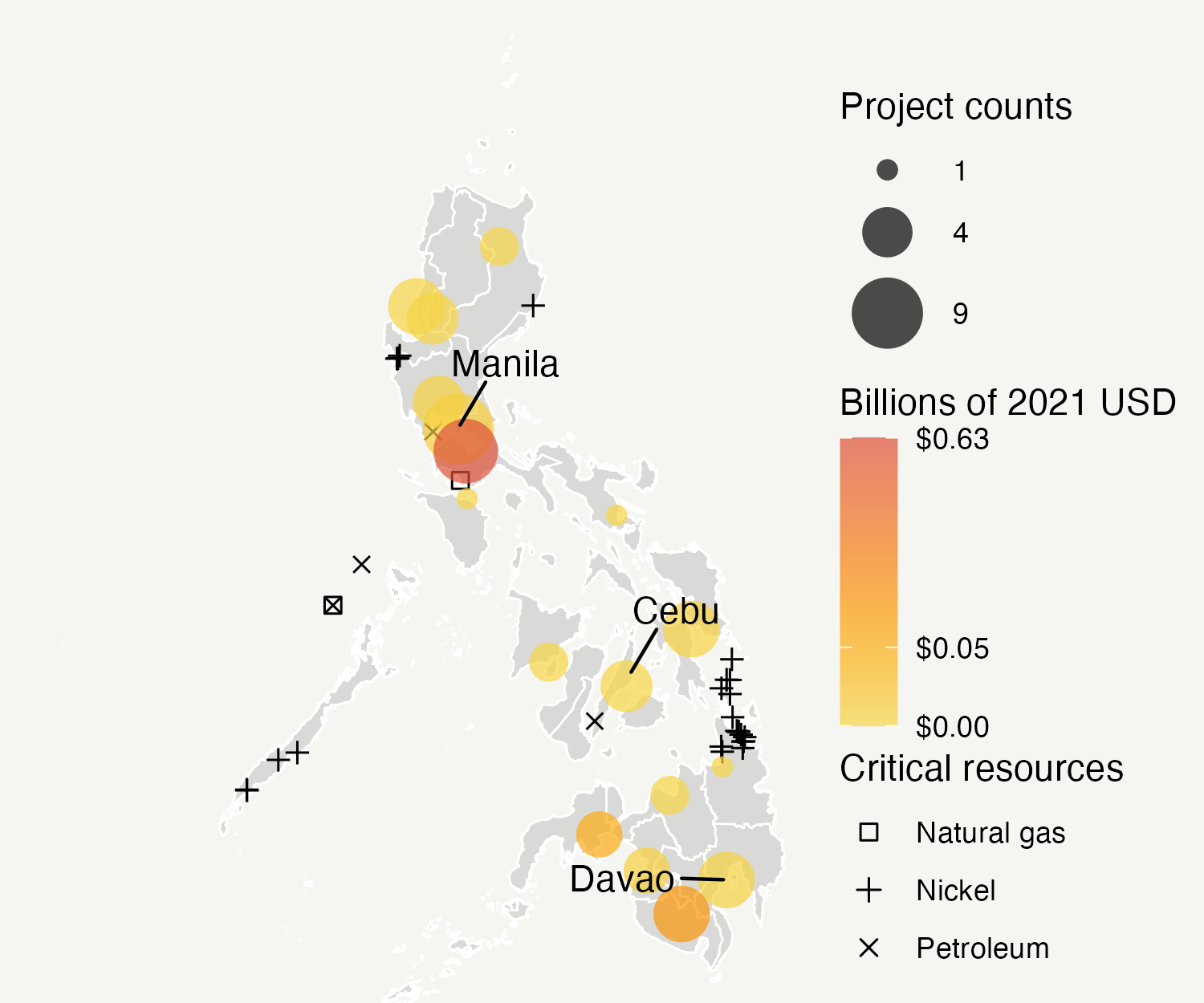

Figures 2.7a and 2.7b: PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines by region, 2000-2021

Mega projects (over $1M)

Goodwill projects (under $1M)

The National Capital Region (NCR), the country’s political epicenter and home to many of its largest companies, received the most projects by count (45 projects) and second-most by value (US$1.3 billion) (Table 2.8). Neighboring Central Luzon received the greatest value of PRC projects (US$2.7 billion), concentrated in the south. Central Luzon is the home region of President Arroyo, who declared her interest in developing the Luzon Urban Beltway as a “globally competitive industrial and service center” (E.O. 561, 2006). Beijing funded several projects related to this goal, including a series of container inspection scanners in 2007 and the GNPower Mariveles Coal Plant in 2010.[12]

Table 2.8: PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines by region, 2000-2021

|

Region name |

Project count |

Total project value, millions USD |

Project value per capita, USD |

|

National Capital Region (NCR) |

45 |

1,284.27 |

95.24 |

|

Region III (Central Luzon) |

26 |

2,659.16 |

214.07 |

|

Region XI (Davao Region) |

26 |

238.73 |

45.53 |

|

Region I (Ilocos Region) |

11 |

222.06 |

41.89 |

|

Region IV-A (Calabarzon) |

10 |

634.07 |

39.15 |

|

Region VII (Central Visayas) |

10 |

0.86 |

0.11 |

|

Region X (Northern Mindanao) |

10 |

1,161.96 |

231.34 |

|

Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) |

9 |

33.91 |

18.86 |

|

Region VIII (Eastern Visayas) |

9 |

58.42 |

12.85 |

|

Bangsamoro Autonomous Region In Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) |

7 |

61.57 |

13.98 |

|

Region XIII (Caraga) |

6 |

61.64 |

21.98 |

|

Region VI (Western Visayas) |

5 |

56.25 |

7.07 |

|

Region XII (Soccsksargen) |

5 |

127.51 |

26.01 |

|

Region II (Cagayan Valley) |

4 |

33.96 |

9.21 |

|

Region V (Bicol Region) |

4 |

82.43 |

13.55 |

|

Mimaropa Region |

3 |

0.68 |

0.21 |

|

Zamboanga Peninsula |

3 |

56.84 |

0.00 |

|

Unspecified |

86 |

1,342.24 |

NA |

Notes: This table shows PRC-funded development projects by region between 2000 and 2021 (inclusive of aid and debt instruments) by number of projects, dollar value (in millions of constant 2021 USD), and dollar value per capita based on 2020 census figures. “Unspecified” indicates that projects were either national/cross-regional in nature or were otherwise unable to be conclusively linked to a specific region. Sources: AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0 for 2000-2021 (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022); Philippine Statistics Agency 2020 Census of Population and Housing.

Davao, another politically important region, is the home of former President Rodrigo Duterte and current Vice-President Sara Zimmerman Duterte-Carpio. Although the total dollar value of PRC projects is moderate (US$239 million), the number of projects is the second-highest in the country (26 between 2000 and 2021). Timing plays an important role: 85 percent of Beijing’s projects were committed after Duterte’s election in 2016. These projects were more about soft power than economic return and included donations of educational materials, medical supplies, emergency food relief, and motorcycles for the Davao City police department.

PRC financing did not shy away from the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), despite the armed conflict in Marawi. Beijing instead identified an opportunity to bolster President Duterte following one of his administration’s defining domestic crises. From 2017 through 2019, the PRC financed seven projects in the region, principally focused on relief and reconstruction efforts in Marawi City, but expanded to funding Dito Holdings Corporation to install a nationwide 4G/5G system in 2019, positioning it as the third telecommunications player in the Philippines alongside Globe and PLDT/Smart.

Energy potential was another factor in the direction of PRC development finance; however, the rationale was not necessarily about proximity to raw energy resources and critical minerals.[13] PRC state-backed investments do not overlap with regions with the greatest concentration of nickel mines (Carraga and Mimaropa) or proximity to oil and natural gas deposits[14] (Calabarazon, Central Visayas, Central Luzon) (see Figures 2.7a and 2.7b, above). Instead, Beijing’s interests appear to lie in boosting local electricity consumption to unlock increased productivity and follow-on projects for Chinese firms.

The Alegria Oil Field in Cebu, in the Central Visayas region, is the only petroleum site identified that was directly operated by a PRC company, China International Mining Petroleum Co., Ltd. (Trimmer et al., 2024; Padayhag, 2014). However, there were no apparent direct connections to concentrations of Chinese official development finance. Instead, the large coal-powered GNPower sites in Central Luzon and Northern Mindanao appear to be the main anchors for additional PRC investment, including both official development finance and FDI—a theme we will further explore in the next section.

2.2 How has Chinese FDI changed over time, in both absolute terms and in relation to the PRC’s development finance?

Beijing’s state-directed development finance across the Philippines is substantial but sensitive to changes in political administrations and concerns over the degree of risk in its global debt portfolio. Moreover, discrete development finance investments are also time-limited rather than long-term. By comparison, FDI implies a longer-lasting ownership stake or financial interest between individual or corporate investors in one economy and another (OECD, n.d.a and n.d.b). The trends described here reflect new inbound FDI annually, not the stock or total value of all previous and current FDI in a given year.

Between 2010 and 2023, new commitments of inbound Chinese FDI to the Philippines skyrocketed by 514 percent, from US$214 million to US$1.3 billion.[15] This growth was by no means steady. As with the PRC’s development finance (section 2.1), Chinese FDI in the Philippines fluctuated dramatically year-on-year. Inbound FDI commitments from China peaked in 2018 with US$11.2 billion announced (Figure 2.9), accounting for 44 percent of new projects that year and roughly half of the growth in the Philippines' global FDI inflows that year (Figure 2.10). By contrast, just two years prior, in 2016, Chinese FDI comprised just under 8 percent of the total inbound investment.

Figure 2.9: Annual inbound Chinese FDI versus global FDI to the Philippines, 2010-2023

Figure 2.10: Annual inbound Chinese FDI as share of total FDI in the Philippines, 2010-2023

The 2018 investments followed the Philippines’ hosting of two ASEAN summits in 2017, where President Duterte courted leaders from the PRC, the U.S., Japan, and the European Union, among others (Heydarian, 2017). Duterte’s 2017 diplomatic press aligned with the first anniversary of his “Build, Build, Build” Infrastructure Program. The ASEAN summits served as a valuable expo for the Philippines to pitch potential investors and mobilize billions of pesos in infrastructure and transportation projects.

Two massive steel projects undergirded Chinese FDI investment commitments in 2018: a US$3.5 billion investment by the state-owned company Panhua Group Co. Ltd. to build a new steel mill and port facility (Canivel, 2018)[16] and a US$4.4 billion joint venture announced by the state-owned enterprise Hesteel Group in conjunction with SteelAsia Manufacturing Corp[17] (Asia Times, 2018; Choo and Fox, 2018). Both of these pledged investments aimed to expand steel production capacity in the state-owned Philippines Veterans Investment Development Corporation (PHIVIDEC) Industrial Authority’s 3,000-hectare estate in Misamis Oriental Province, Northern Mindanao.[18]

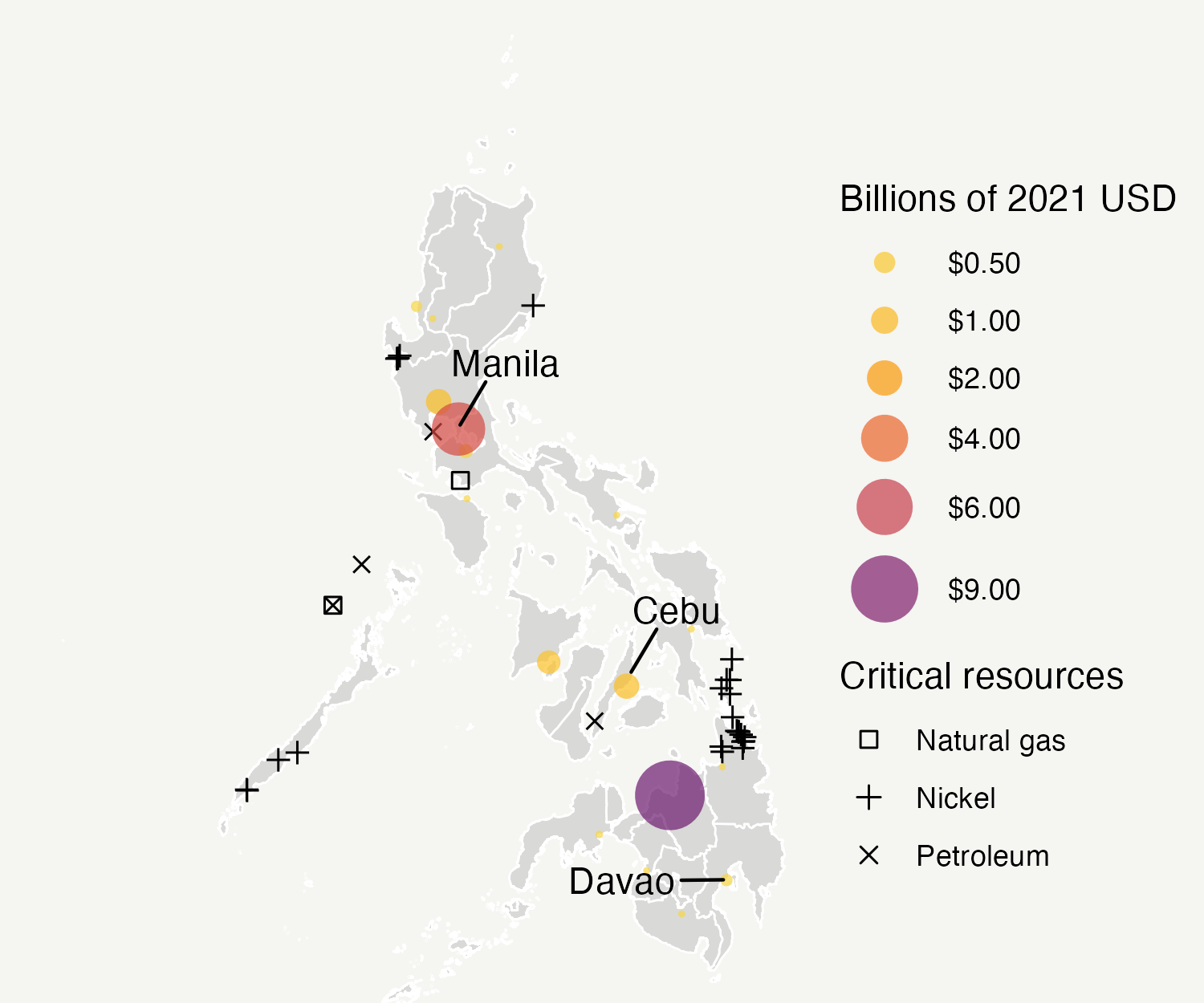

Critical minerals do not readily explain the geography of inbound Chinese FDI in the Philippines. Caraga and Mimaropa account for over three-quarters of the country’s viable nickel production sites, but neither region attracted a single Chinese FDI project (Figure 2.11).[19] Hydrocarbons are a similar refrain. Although China International Petroleum Company Limited has explored petroleum extraction from the Alegria Oil Field in Central Visayas since 2012 (Padayhag, 2014; Polyard Petroleum International Group, Ltd. 2012), the region attracted less than 4 percent of inbound Chinese FDI.

The main reported energy investments in Central Visayas and Central Luzon were instead power generation for domestic consumption, as opposed to refining or exporting petroleum (Griffiths, 2019). 2017 talks between Philippine Trade Secretary Ramon Lopez and a Chinese firm (Handi Group) about investing in a Northern Mindanao petroleum refinery (Campos, 2017; DTI, 2017; Handi Group, 2017; Philippine Star, 2017) failed to progress beyond an initial handshake.

Figure 2.11: Critical natural resources and inbound Chinese FDI in the Philippines, 2010-2023

Instead, these inbound FDI flows may be more a reflection of three other strategic factors: (i) proximity to existing PRC-funded development projects; (ii) tax incentives; and (iii) a pivot to producing higher value-added projects. The 2018 Chinese FDI investments in two Misamis Oriental steel factories (contributing to the 72 percent Chinese share of all FDI in the metals sector) are a useful illustration of these dynamics. The two new FDI commitments were announced less than two years after a PRC development finance agreement was reached to construct a power plant in neighboring Lanao del Norte province (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022).[20] Just 75 miles down the coast from the PHIVIDEC Industrial estate, the power plant offers cheap electricity[21] to power the operations of the two steel factories (GNPower, n.d.). The integration of the factories within the PHIVIDEC industrial estate was also an attractive proposition—as the state-owned enterprise offers various incentives to attract foreign investment, from low-priced land leases to tax exemptions (PHIVIDEC, n.d.a.).[22]

Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) for the Panhua and Hesteel plants were personally signed by then Secretary of Trade and Industry Ramon Lopez (Canivel, 2018; Choo and Fox, 2018), underscoring the high alignment of interest at the time between private Chinese investors,[23] the Duterte administration,[24] and Philippine companies. In fact, local organizations, such as the left-leaning think tank IBON Foundation, have criticized the coziness between local mining interests and foreign steel manufacturers in the Asia-Pacific region, arguing that the Philippines should either process more minerals for domestic construction purposes or export a higher value-added product than raw ores (IBON Foundation, 2017).

Comparatively, China is underrepresented as a share of inbound FDI supporting other sectors of the Philippine economy. This asymmetry is noticeable in the tourism and leisure industry—the single largest sector in terms of inbound FDI overall (Table 2.12). Aside from a US$850 million joint venture investment in 2012 by Jin Jiang International Investments Co. of Shanghai with Liwayway Marketing Corporation to build 28 economy hotels, Chinese investors have been markedly less interested in this sector than their peers in other countries (Gonzalez, 2012; Travel Weekly Asia, 2016).[25]

The ramp-up of Chinese FDI in the metals industry has mobilized substantial inflows of capital, but not without setbacks. The Panhua steel plant was unable to start construction by the end of 2019 as planned and was stalled until it was restarted in May 2022 (Desiderio, 2019; DFA, 2022). There have been unconfirmed reports of work permit violations[26] related to another Panhua steel plant in Sarangani province that came under scrutiny in 2021 (Gubalani, 2021; Rebollido, 2021). We further explore concerns regarding the economic, environmental, and social outcomes of PRC financing for development in Chapter 4.

Table 2.12: Inbound Chinese FDI versus total FDI by sector in the Philippines, 2010-2023

| Sector | PRC-sourced FDI, billions USD | All source FDI, billions USD | PRC share of FDI |

| Metals | 8.78 | 12.18 | 72.08% |

| Hotels and tourism | 3.71 | 20.97 | 17.68% |

| Coal, oil, and gas | 2.04 | 11.47 | 17.80% |

| Real estate | 1.66 | 9.50 | 17.46% |

| Financial services | 0.98 | 6.68 | 14.63% |

| Non-automotive transport original equipment manufacturer (OEM) | 0.96 | 1.67 | 57.61% |

| Consumer products | 0.74 | 2.37 | 31.27% |

| Leisure and entertainment | 0.66 | 0.86 | 77.25% |

| Automotive original equipment manufacturer (OEM) | 0.60 | 1.38 | 43.15% |

| Communications | 0.55 | 3.49 | 15.84% |

Notes: This table shows the top ten sectors for (i) total inbound Chinese FDI and (ii) FDI from all sources in the Philippines from 2010 through 2023. FDI dollars represent capital expenditures (CAPEX) in billions of 2021 USD. Sources: fDi Markets, from the Financial Times Ltd.

3. Relationships

Key insights in this chapter:

- Chinese development finance in the Philippines increasingly relies on 101 global banks from Asia, Europe, and North America to pool risk and mobilize capital

- Beijing’s reliance on 37 Chinese state-owned enterprises to implement its projects is problematic: 43 percent are linked to questionable financial practices

- Recipients of PRC financing are often located in politically or economically important regions or have links to mainland China or the Filipino-Chinese diaspora

Beijing is one of the largest financiers of overseas development projects globally but it is not a unitary actor. What was once the purview of a bounded number of Chinese players has expanded to an extensive network of suppliers that cross international boundaries and have varying reputations for their transparency, follow-through, and outcomes. However, this is only one side of the picture: for every project that Beijing bankrolls, it must also have a willing counterpart. In fact, the PRC’s development finance in the Philippines involves a vast universe of government agencies, policy and commercial banks (state-owned and private sector), non-governmental organizations, and companies to take these activities from idea to delivery.

In this chapter, we scrutinize the relationships behind these investments: how many players, who are they, what roles do they play, and are some more important than others? As a starting point, we used the project-level information described in Chapter 2 to identify entities involved in PRC development projects via financing, co-financing, or implementation (supply side) or listed as recipient entities (demand side). We then developed profiles of the attributes of these entities by accessing large industry databases (e.g., GlobalData Explorer, FitchConnect) and desk research. We also employed the Factiva Dow Jones News and Analysis database to gauge media coverage of these actors to understand how they are perceived locally.

3.1 Supply side: Who finances and implements PRC projects?

There is a staggering number of players involved in the supply of PRC-financed development projects in the Philippines. Over roughly two decades (2000-2022), we identified 228 discrete entities involved in financing or implementing such activities. These players were surprisingly diverse, hailing from 24 countries or territories (Figure 3.1). While the majority were headquartered in China (95) or the Philippines (56), one-third of these entities span other parts of Asia, Europe, and North America.

Figure 3.1: Headquarters of financiers and implementers of PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines, 2000-2022

Sources: AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0 for 2000-2021 (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022). Supplemented by limited desk research and media article review by the research team to identify additional projects and details for 2022.

Some actors supplied primary financing in the form of aid (e.g., grants and no- or low-interest loans) or debt (e.g., loans approaching market rates and export credits). Since we are interested in PRC-financed development investments, all 52 primary financiers were, by definition, from mainland China. Two-thirds of these actors were less consistent in supporting the Philippines’ development—bankrolling just one project in the country over the time period. By contrast, the top 15 financiers were mentioned in two or more projects (Figure 3.2). Figure 3.3 illustrates the interconnectedness of these actors, where financiers and recipients overlap across multiple projects.

Two state-owned commercial banking groups—Bank of China (BOC) and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), and their subsidiaries—along with the state-owned policy banks of Export-Import Bank of China (Eximbank) and the China Development Bank (CDB) have outsized importance in not only the number of projects they support but also the volume of the financing they mobilize. These banks typically bankroll larger infrastructure projects such as BOC’s and CDB’s investments in power plants and telecommunications (e.g., coal-fired power plants in Lanao Del Norte and Mariveles, as well as DITO Telecommunity Corporation’s network of towers), Eximbank’s interest in irrigation, power, and technology (e.g., the Kaliwa Dam, a Chico River irrigation project, and Safe City initiatives with 18 local government units), along with ICBC’s syndicated loans (e.g., for San Miguel Corporation, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, and Jobin-SQM, Inc).

Under the purview of the PRC’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), the Chinese embassy in Manila and its three consulates (in Davao City, Laoag, and Cebu City) are at the front lines of Beijing’s engagements with Filipino counterparts. These representational institutions tend to finance a large number of small-dollar projects positioned to win hearts and minds. In contrast to other financiers, frequent thematic areas of focus of these diplomatic institutions include educational cooperation (e.g., donating textbooks and computer equipment to local schools), visible support to healthcare systems (e.g., distributing masks and medical supplies to local hospitals and health clinics), and humanitarian assistance (e.g., supplying rice and other food aid).

In a similar vein, Hanban (renamed in 2020 as the Ministry of Education Center for Education and Cooperation, CLEC) was also a top financier of educational cooperation projects related to opening Confucius Institutes (CIs) with local university counterparts such as Ateneo de Manila University, Angeles University Foundation, Bulacan State University, and the University of Philippines Diliman. As part of Hanban’s 2020 rebranding, Beijing moved oversight and funding of the Confucius Institutes into a separate non-profit, charitable organization—the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF). Observers largely saw the decision as a defensive posture in response to international scrutiny and criticism over the PRC’s influence over CIs (Sharma, 2022).[27]

The PRC’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), another line ministry that is a top financier, has more of a commercial orientation to its projects, given its mandate to advance China’s economic interests (Mathew and Custer, 2023). MOFCOM projects focus on large-scale connective infrastructure to improve market access and ease the flow of goods. High-profile examples of such projects include bridges (such as the Bucana or Davao River Bridge, Estrella-Pantaleon Bridge, and Binondo-Intramuros Bridge), roads (Davao City Expressway), and the rehabilitation of Marawi City in Mindanao, among others. Nevertheless, even with MOFCOM’s commercial orientation, these example projects were outliers for Beijing, in that they were financed with more generous grants akin to official development assistance, rather than the debt instruments it typically favors.

Unlike many other leading bilateral suppliers, the PRC does not disclose the details of its development finance activities via internationally accepted reporting regimes like the OECD’s Creditor Reporting System or the International Aid Transparency Initiative. Instead, tracking Beijing’s state-directed aid and debt in the Philippines requires painstaking work by AidData and other third parties to piece together data points from multiple sources meticulously.[28] This context may explain why the most frequently mentioned financier is an “unspecified Chinese government institution.”

Figure 3.2: Top 15 primary financiers of PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines, 2000-2022

Figure 3.3: Top PRC financiers and their recipients in the Philippines, 2000-2022

Many of the PRC’s big-ticket infrastructure projects crowded in co-financiers from China and internationally to mobilize additional capital, pool risk, or facilitate debt refinancing. The number of co-financiers per project varies widely, from one or two additional actors in smaller projects to double-digits in the larger ones. In the Philippines, we identified 101 co-financiers of PRC-financed development projects, 68 percent of which were private sector entities. This dynamic is consistent with Beijing’s increasing use of “collaborative lending arrangements with Western commercial banks and multilateral institutions” globally in an effort to borrow their risk management expertise in vetting borrowers and project viability (Parks et al., 2023).[29]

These co-financing institutions were most often from the financial services sector with extensive international operations in investment management and commercial banking, as well as insurance, foreign exchange, and other capital market solutions. There was strong representation from across Asia among these co-financiers, including Taiwan (17), Japan (12), the Philippines (11), and Malaysia (4). However, not all of the co-financiers were equally important in terms of the consistency of their engagement in PRC-financed development projects. Roughly 40 percent of the co-financiers were involved with only one Philippines project each.

By contrast, the top 22 co-financiers (by project count) each supported five or more projects over two decades (Figure 3.4). Well-known names in Europe’s banking sector—the United Kingdom’s Standard Chartered Bank PLC and HSBC Bank PLC, the Netherlands’ ING Group NV and ABN AMRO, and Germany’s state-owned Norddeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale (NORD/LB) featured prominently in the list of top co-financiers. They were joined by U.S. commercial banks (Citigroup and First Commercial Bank Limited) and an Australian banking conglomerate, ANZ Group.

Figure 3.4: Top 22 co-financiers of PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines, 2000-2021

Another critical component of the PRC’s capacity to deliver development projects is its stable implementation partners. In the Philippines, this group includes 88 identified implementers, representing a smaller set of countries than the other roles. Since Beijing is known for tying access to financing to the use of Chinese implementers (Horn et al., 2019),[30] it stands to reason that Chinese firms, agencies, or organizations account for the second-largest group of implementers (41 entities). Philippine government agencies, non-profits, and private sector entities were also frequently referenced in projects as implementers (45 entities), either alone or in concert with a Chinese partner.

The top 20 implementers overall were identified as supporting three or more projects (Figure 3.5). Over half of these actors were focused on physical infrastructure (e.g., energy and utilities, construction, and transportation) or digital connectivity (e.g., telecommunications and technology). This profile aligns with one of Beijing’s stated motivations for its overseas development finance and the Belt and Road Initiative: to open up raw materials, energy supplies, and export markets for Chinese goods and services through increased connectivity within and between countries (Mathew and Custer, 2023; Hillman and Sacks, 2021). Other entities emphasized education projects that advance Beijing’s reputation-building objectives or humanitarian response in one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries (ADB, 2021). Implementers often have long-standing relationships with Philippine counterparts, as underscored by Figure 3.6 which visualizes the connections between recipients who partner with the same implementer in three or more projects.

Figure 3.5: Top 20 implementers of PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines, 2000-2021

Figure 3.6: Top Philippine recipients of PRC-funded development projects and their implementers, 2000-2022

Chinese state-owned companies were among the most prolific implementers across numerous PRC-financed projects in the Philippines. This trend is not unique to the Philippines. It is part of the design and delivery of the BRI, which is an extension of Beijing’s 1999 “Going Global” (or “Going Out”) strategy that seeks to export excess capacity in its construction, steel, and cement industries and put this to productive use abroad in ways that advance the PRC’s national interests (Mathew and Custer, 2023). As state-owned companies, many of the Chinese entities on the list of top implementers ultimately report to the same oversight body: the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the PRC’s State Council (SASAC).

Within China’s heavily state-planned economy, SASAC plays an outsized role in guiding the productivity and direction of Chinese SOEs and their estimated $30.48 trillion in total assets (SASAC, 2022). For example, one of the top 20 implementers (by number of projects) in the Philippines, China State Construction Engineering Company (CSCEC), is a SASAC subsidiary that has been involved in the design and delivery of a wide variety of physical infrastructure (e.g., power plants, airports, and tunnels) worldwide and in the Philippines.

SASAC also oversees the China Communications Construction Company (CCCC), which has outsized involvement in a large number of projects in the Philippines, primarily through its extensive network of subsidiaries. Collectively CCCC and its subsidiaries are a go-to implementer for BRI projects related to transportation and power infrastructure—from construction and dredging to manufacturing and export services. This includes CCCC Highway Consultants Company, Ltd., China Railway 25th Bureau Group, and China Road and Bridge Company, which all feature in the top 20 implementers list in their own right. CCCC is also the parent company for China Harbour Engineering Company, Ltd. and China Dredging, which have also been involved in Philippine development projects.

Other state-owned corporations in the construction and power sectors round out the list of Chinese implementers, including Shanghai Electric Power Construction Co., Ltd. (power transmission and distribution), China National Machinery and Equipment Group (agriculture, industrial, and power projects), and China National Construction & Agricultural Machinery Import & Export Corporation (import-export of heavy equipment). Leading Chinese technology companies also feature prominently on the list. Nuctech (formerly Tongfang Vision Technology Co, Ltd.), a state-owned company, provides advanced security and inspection solutions for civil aviation, customs, and other industries. The partly state-owned ZTE Corporation[31] and the state-influenced Huawei Corporation (private sector in name, but with an opaque ownership structure and suspected ties to the Chinese Communist Party)[32] are household names in the information and telecommunications technology industry.

All but one of the Philippine actors in the top 20 implementers were government agencies, SOEs, or public universities. There was only one private sector firm: San Miguel Corporation. Many of the Philippine entities had mandates related to the PRC’s traditional emphasis on hard infrastructure sectors and were often jointly named as implementers alongside a Chinese counterpart. For example, the Philippine Bureau of Customs partnered with the Chinese technology company Nuctech to develop inspection systems (e.g., mobile x-rays to inspect container vehicles and luggage) to detect illegal drugs and other harmful items at critical international transit points such as the ports of Manila and Subic Bay and Ninoy Aquino International Airport, among others.

The state-owned Philippine Bases Conversion and Development Authority (BCDA) previously worked with Chinese actors such as China Gezhouba Group Ltd. and China Road and Bridge Corporation to transform former U.S. military bases into alternative productive civilian use, including projects related to Bonifacio Global City and New Clark City. The Philippine Presidential Communications Office collaborated with the China Electronic Engineering Design Institute to jointly implement a project to expand the country’s state radio and television broadcasting network.

Looking across all three supplier roles (financier, co-financier, implementer), we can better understand the profile of entities involved in PRC development projects in the Philippines. Outside of government entities, these actors cluster around three thematic areas: financial services, hard infrastructure sectors (construction, energy and utilities, and telecommunications), and the social sector (educational cooperation and humanitarian response and recovery), as shown in Table 3.7. Chinese (41 percent) and Filipino (24 percent) actors are the two most prevalent nationalities among suppliers. However, co-financiers were more heavily drawn from a more diverse set of third-country actors (35 percent).

Of the more than 200 entities that finance or implement PRC development projects in the Philippines, private sector entities from third countries are the most frequent type (60), almost exclusively providing co-financing support to one or more Chinese primary financiers. There is a heavy state orientation in the remainder of entities, including Chinese state-owned companies (38); Chinese government or other public agencies (38); Philippine government or other public agencies (27); third country state-owned funds, commercial or policy banks (16); and Chinese state-owned fund, commercial or policy banks (11).

Table 3.7: Suppliers of PRC-funded development projects in the Philippines, by sector and role, 2000-2022

3.1.1 Polarized views of Chinese implementers in the Philippines

If money is indicative of priorities, then Beijing has demonstrated a clear preference for bankrolling big-ticket physical and digital infrastructure projects in the Philippines and globally over the last two decades. By virtue of their design, these projects have the potential to be transformative—fundamentally altering transportation, commerce, communication, and power generation systems in positive ways. Nevertheless, if implementation breaks down, the economic, environmental, social, and governance ramifications of these projects for communities are experienced at a much larger scale.

Several features of Beijing's design and delivery of development finance raise the stakes by creating perverse incentives for implementers to cut corners, collude with local counterparts, or fail to mitigate negative spillover effects for communities. These features include opaque assistance terms, limited competitive procurement, and weak reporting requirements on implementation and outcomes. Given the high-profile nature of the PRC’s investments in critical industries and infrastructure in the Philippines, it can be difficult to separate myth from fact when it comes to the reputation and follow-through of its implementers.

One of the most objective measures we can use to lay some groundwork is the World Bank’s (n.d.) long-standing administrative sanctions process, which aims to detect and deter what it refers to as “sanctionable practices”: fraud, corruption, coercion, collusion, or obstruction by firms and individuals. The World Bank has sanctioned (or debarred) over 700 firms and individuals publicly since 2001 for questionable business practices (ibid).[33] The Asian Development Bank also maintains its own database. Debarred firms are prohibited from working on projects financed by the sanctioning entity for a defined period of time. If a firm has been sanctioned by the World Bank or the Asian Development Bank at some point, this does not preclude a country like the Philippines from awarding the entity in question a contract to implement a given development project using its own domestic procurement processes. The value of this measure is better understood as reflective of the risks of engaging with certain firms that have been associated with questionable financial practices.

For each of the 88 identified implementers of PRC-financed development projects in the Philippines, we used the databases of the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, supplemented by additional desk research, to assess whether any of these actors had been debarred or sanctioned either in the past or at present.[34] Accordingly, we identified that 16 of the 37 Chinese state-owned enterprises (43 percent) involved in PRC-funded projects in the Philippines had either been directly sanctioned by one of the two multilateral processes or indirectly through parent-subsidiary company relationships. Table 3.8 provides a detailed list of each Chinese firm involved in Philippine development projects at some point in the last two decades that was directly or indirectly sanctioned by the World Bank Group or the Asian Development Bank.[35]

In addition to the World Bank Group sanctions process, bilateral actors such as the United States government have also developed lists of sanctioned firms. In 2020, for example, the U.S. Commerce Department released a list of 24 Chinese firms it had identified as abetting the PRC military to construct and militarize artificial islands in the South China Sea (West Philippine Sea) as part of Beijing’s bid to exert its maritime territorial claims (Gan, 2020). Given the relevance to the Philippines’ territorial sovereignty, along with the fact that this issue has also been hotly debated in local media and political discourse, we have also identified in the table any implementers that were directly or indirectly identified on the U.S. blacklist for engaging in the construction of artificial islands.

Table 3.8: PRC implementers sanctioned or debarred for questionable business practices by the World Bank Group or the Asian Development Bank, 2000-2022