Balancing Risk and Reward:

Who benefits from China’s investments in Indonesia?

Samantha Custer, Bryan Burgess, Han Kyeol Kim, Muhammad Faiz Krisnadi, Kelsey Marshall, Divya Mathew, Felix Patrick, Alland Dharma Saputra, Jonathan A. Solis, Narayani Sritharan

June 2025

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Samantha Custer, Bryan Burgess, Han Kyeol Kim, Muhammad Faiz Krisnadi, Kelsey Marshall, Divya Mathew, Felix Patrick, Alland Dharma Saputra, Jonathan A. Solis, Narayani Sritharan. John Custer and Sarina Patterson supported this publication’s layout, editing, and visuals. The cover design is by Sarina Patterson, with photos of the Suramadu bridge (left) and the Jakarta–Bandung High-Speed Rail (right) by Dodo Hawe and Habib Farindra, respectively, via Adobe Stock, used under the Standard license. This study was conducted by AidData, a U.S.-based research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute, in collaboration with Indonesia’s Foreign Policy Talks. We acknowledge Noto Suoneto for his helpful review and feedback, which strengthened the analysis and findings of this report. We thank the seven Indonesian experts from media, think tanks, government, civil society, and academia who graciously shared their insights via background interviews. This research was made possible with generous support from the United States Department of State. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders and partners.

Citation

Custer, S., Burgess, B., Kim, H.K., Krisnadi, M.F., Marshall, K., Mathew, D., Patrick, F., Saputra, A.D., Solis, J.A., and N. Sritharan. (2025). Balancing Risk and Reward: Who benefits from China’s investments in Indonesia?. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary.

1.1 Indonesia-China relations: An evolving story

1.2 Tracking Beijing’s economic statecraft in Indonesia

2.1 How has the PRC’s development finance changed over time and relative to the alternatives?

2.1.1 How does Beijing compare with other development partners?

2.1.1.1 Comparing the terms of Beijing’s assistance relative to others

2.1.1.2 Comparing Beijing’s assistance trajectory relative to others

2.1.1.3 Comparing Beijing’s sectoral focus relative to others

2.1.2 How do flows of Chinese development finance vary across ASEAN?

2.2 How has Beijing’s financing varied across administrations?

2.2.1 Abdurrahman Wahid (1999-2001)

2.2.2 Megawati Soekarnoputri (2001-2004)

2.2.3 Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (2004-2014)

2.3 In which communities is China investing—and why?

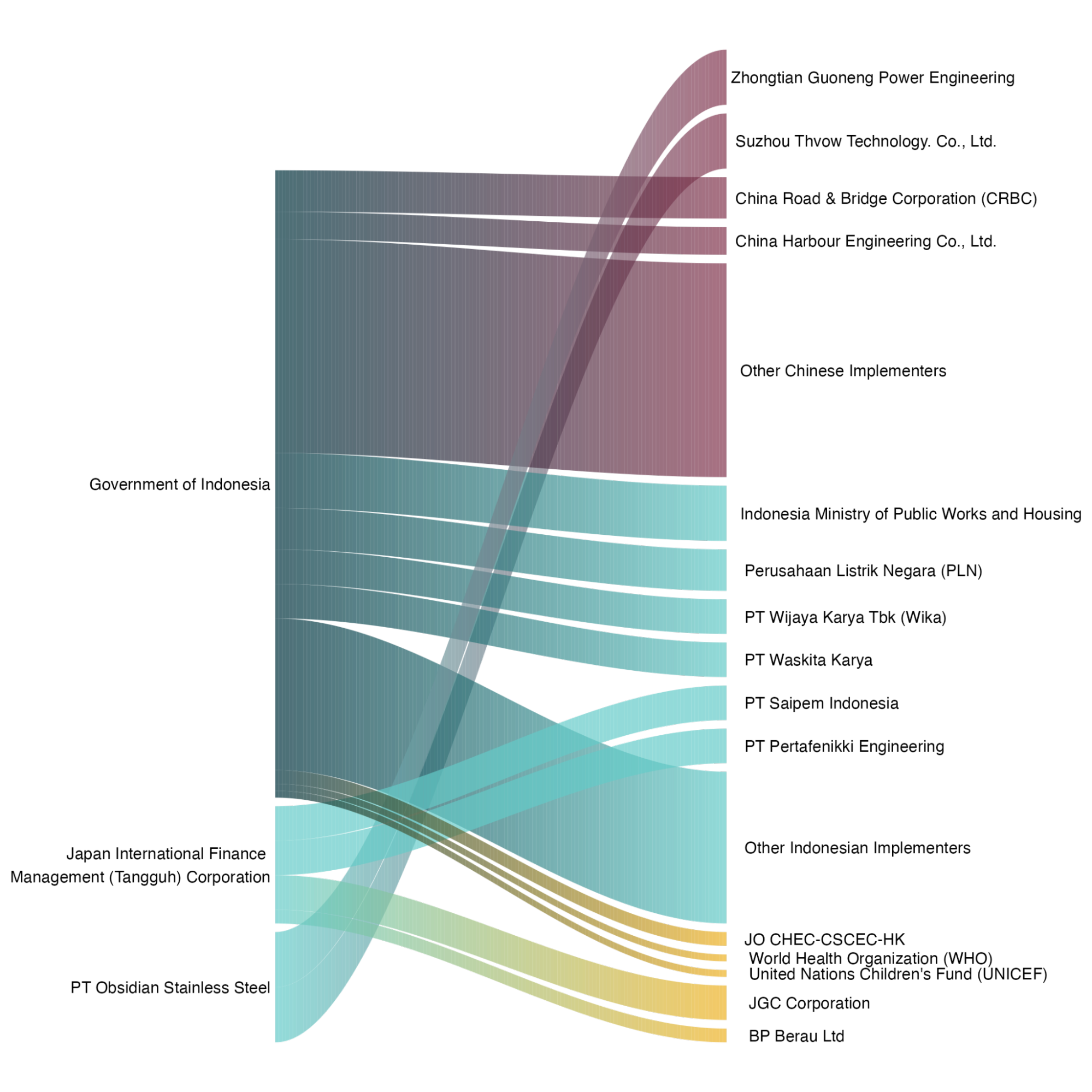

3.1 Supply side: Who finances and implements PRC-backed development projects?

3.1.1 Views of Chinese implementers in Indonesia

3.2 Demand side: Who are the primary recipients of PRC investment projects in Indonesia?

3.2.1 Which firms and agencies have the greatest exposure to Beijing?

4.1.1 From commitments to delivery: How fast does the money move?

4.1.2 Failure to deliver? Project suspensions and cancellations

4.2.1 Early warning indicators of ESG risk in PRC-financed projects

4.2.2 Exposure to performance risk in Chinese-financed projects

4.3.1 Winning hearts and minds? Perceptions and financing

4.3.2 Public good or public harm? Outcomes of Chinese financing

4.3.2.1 PRC financing and Indonesian economic outcomes

4.3.2.2 PRC financing and Indonesian environmental outcomes

4.3.2.3 PRC financing and Indonesian social and governance outcomes

5.1 Revealed priorities: What projects, when, and where?

5.2 Influence networks: Which players, what roles, and why?

5.3 Weighing trade-offs: Follow-through, costs, and benefits?

Figure 2.2: Total official finance commitments from China to Indonesia, 2000-2023

Table 2.4: Top 10 sectors of PRC-funded development projects in Indonesia, 2000-2023

Table 2.6: Total PRC development finance commitments to ASEAN countries, 2000-2021

Figure 2.7: PRC-funded development projects in Indonesia, 2000-2023

Box 1. Surabaya–Madura (Suramadu) Bridge

Box 2. The Jakarta–Bandung High-Speed Railway (HSR)

Box 3. The Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP) and nickel production

Figure 2.9: Chinese-funded development projects in Indonesia by province, 2000-2023

Table 2.10: Official PRC projects in Indonesia by province, 2000-2023

Figure 2.11: Inbound Chinese and global FDI to Indonesia, 2010-2024

Table 2.12: Inbound Chinese and global FDI to Indonesia, 2010-2024

Figure 2.13: Inbound Chinese FDI as a share of total FDI in Indonesia, 2010-2024

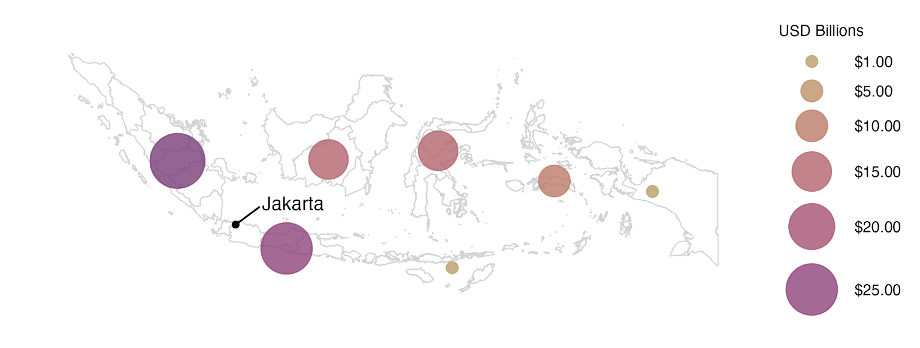

Map 2.14: Chinese inbound FDI in Indonesia by region, 2010-2024

Table 2.15: Chinese inbound FDI in Indonesia by region, 2010-2024

Box 4. Exploiting synergies between development finance and Chinese FDI in Sumatra

Table 2.16: Selected sectors, inbound Chinese and global FDI in Indonesia, 2010-2024

Table 3.2: Top 10 financiers of Chinese-funded development projects in Indonesia, 2000-2023

Figure 3.3: Top Chinese financiers and their recipients in Indonesia, 2000-2023

Table 3.4: Top 15 co-financiers of Chinese-funded development projects in Indonesia, 2000-2023

Table 3.5: Top nine implementers of Chinese-funded development projects in Indonesia, 2000-2023

Figure 3.9: Indonesian recipients of Chinese funding by sector, 2000-2023

Table 3.10: Recipients of Chinese-funded development projects in Indonesia, 2000-2023

Table 3.12: Top 15 recipients of Chinese funding in Indonesia by dollar value, 2000-2023

Table 4.1: Average time between stages of PRC-funded development projects in Indonesia, 2000-2022

Table 4.5: PRC-funded development projects in Indonesia with newly identified ESG risks, 2000-2021

Table 4.6: ESG risks in PRC-funded development projects in Indonesia by sector, 2000-2021

Table 4.7: Performance risk and Chinese implementers of development projects in Indonesia, 2000-2023

Table 4.8: Top 10 PRC higher-risk implementers by project count and value, 2000-2023

Table 4.9: Top Chinese financiers of Indonesian development projects and performance risk, 2000-2022

Table 4.12: Chinese development finance, Chinese FDI, and economic outcomes in Indonesia, 2005-2023

Figure 4.14: Vegetation trends in Central Sulawesi, 2010-2020

Figure 4.16: Indonesian attitudes towards democracy and the country’s democracy rating, 2000-2023

Executive Summary

Chinese money has gone from a footnote to a headline in Indonesia’s growth trajectory since the early 2000s. Government agencies, state-owned enterprises, and private companies from China have invested large sums in Indonesia’s roads, power plants, and nickel factories. These financial infusions are erratic: big booms one year, sudden lulls the next. This report assesses the money, relationships, and outcomes from roughly two decades of PRC state-directed development finance and private foreign direct investment.

Money: What projects does the PRC finance, where, when—and why?

Beijing bankrolls ambitious, risky projects in Indonesia’s energy, transport, and extractives sectors that have the potential to generate commercial returns and advance BRI aspirations, while responding to domestic political priorities. The PRC pairs these investments with small-dollar goodwill projects in the social sectors. It deploys state resources strategically (US$69.6 billion in official finance from 2000 to 2023), constructing infrastructure and cultivating goodwill to crowd in market opportunities for Chinese FDI (US$94.1 billion from 2010 to 2024). Inbound investment from Chinese companies has outsized importance, representing one-quarter of new foreign capital expenditures.

As Indonesia’s largest supplier of development finance, Beijing operates more like a commercial lender than a traditional donor, issuing 90 percent of its financing as debt rather than aid. Among its ASEAN peers, Indonesia attracts more of both types of Chinese capital. Regions like Java and Sumatra capture the lion’s share of Beijing’s development finance in absolute terms, but resource-rich West Papua and Central Sulawesi stand out for attracting noticeably more of Beijing’s per capita spending.

Relationships: How many players, who are they, and what roles do they play?

Beijing’s development finance projects in Indonesia are not just made-in-China; they draw upon a global enterprise of 439 discrete entities from 35 countries. Fifty-eight Chinese state-owned policy and commercial banks, government agencies, and diplomatic missions were the primary financiers. These players relied on a multinational pool of 208 co-financiers across Asia, Europe, and North America to raise capital and distribute risk. Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), 14 of whom were sanctioned for questionable financial practices, were the majority but not the totality of Beijing’s 213 implementers.

Just under half of the implementers of PRC projects were Indonesian, including stand-alone firms and participants in joint ventures and special purpose vehicles. Social sector projects capitalize on the credibility and distribution networks of Islamic organizations and universities in Indonesia to win hearts and minds. Six entities received large and frequent infusions of PRC financing, including the Government of Indonesia, Perusahaan Listrik Negara, Lembaga Pembiayaan Ekspor Indonesia, Bank Rakyat Indonesia, Garuda Indonesia, and two telecom companies, Smartel and Smartfren (subsidiaries of the Sinar Mas Group, recently merged with XL Axiata). Indonesian state-owned enterprises were often recipients of funding, but so too were powerful private sector conglomerates like the Bakrie Group (Bumi Resources, Bakrie Telecom, and Bakrie Autoparts) and subsidiaries of Chairul Tanjung’s CT Corp (Trans Retail Indonesia and Trans Media Corpora).

Outcomes: How does Beijing follow through and manage risk, and to what effect?

PRC-financed projects across Indonesia take an average of 2.5 years to move from funds committed to projects delivered, considerably slower than in ASEAN peers like the Philippines. Energy and transport projects are among the riskiest propositions: these activities trigger longer delivery delays (1,000+ days) and greater exposure to environmental and social risks. The choice of implementer is non-trivial, affecting project success and community well-being. Unfortunately, over 40 percent of Beijing’s development finance portfolio (US$30 billion) relied on risky implementers with higher levels of ESG exposure or prior sanctions for questionable business practices. Risky firms were often repeat implementers.

Beijing faces an uphill battle in converting money into reputational gains. Public approval of PRC leadership has soured in Indonesia as economic engagement with China increased. Public, private, and civil society elites attest to Beijing’s influence on domestic development priorities, but have grown more wary of this trend. The potential contribution of Chinese capital to Indonesia’s development has mixed results. Economically, provinces exposed to more Chinese FDI tended to have higher productivity, and those with more of Beijing’s development finance dollars had lower levels of unemployment. Worsening pollution and vegetation levels were not systematically linked to Chinese capital overall, but Indonesia’s Morowali Industrial Park showcases catastrophic impacts in individual projects. Finally, Indonesians may be redefining what it means for democracy to deliver: emphasizing economic development over political rights in ways that are conducive to Beijing’s preferred narratives and value proposition.

1. Introduction

Indonesia’s rapidly growing economy, abundant natural resources, and youthful population make it a sought-after economic partner (ITA, 2023; UNDP, 2024). Geostrategically located next to key maritime trade routes, Indonesia straddles the Strait of Malacca’s western coast (China Power, 2017). Recognizing this, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has deployed its economic statecraft—trade, aid, and foreign direct investment (FDI)—to position itself as a go-to supplier of capital to fuel Indonesia’s growth. New deals are launched with great fanfare, but with limited details and ample controversy.

Without transparent and credible information about what Beijing is investing in, where, and to what effect, it is difficult for the Indonesian public and its leaders to assess the merits and drawbacks accurately. These information asymmetries can increase vulnerability to deceptive messaging about the cost-benefit trade-offs of these partnerships. This is a timely moment to take stock of the trajectory of economic engagement between the two countries, as Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto, who assumed office in October 2024, shapes his foreign policy priorities.

In this report, Balancing Risk and Reward: Who benefits from China’s investments in Indonesia?, we meticulously piece together data from multiple sources to assess the money, relationships, and outcomes from two decades of PRC state-directed development finance and private foreign direct investment (2000-2023). This research was produced by AidData, a U.S.-based research lab at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute, in partnership with Foreign Policy Talks. This respected Indonesian organization is a cross-border platform to facilitate knowledge exchange and discourse among foreign policy thinkers and practitioners.

Drawing upon historical financial analysis, desk research, and interviews with Indonesian experts, this report aims to answer three critical questions:

- Money: What projects does the PRC finance, where, and when, via its state-directed development finance and private sector FDI in Indonesia?

- Relationships: How many players are involved in these projects, who are they, what roles do they play, and are some more important than others?

- Outcomes: To what extent does Beijing follow through on commitments, how does it manage risk, and what are the downstream outcomes?

1.1 Indonesia-China relations: An evolving story

Indonesia-China relations have not always been smooth. Seventeen years after establishing diplomatic relations with the PRC, Jakarta dramatically severed ties in 1967. It alleged Beijing’s involvement in backing an attempted coup by the Indonesian Communist Party. The coup was unsuccessful, and PRC involvement was later found to be limited (Zhou, 2019); however, the episode resulted in the fall of Indonesian President Sukarno and triggered a presidential transition. It would take more than two decades of diplomatic limbo before the two countries resumed relations in 1990.

In the intervening period, the PRC under Deng Xiaoping made a strategic pivot in its foreign policy, pursuing economic liberalization and stabilization to attract international capital and abandoning support for overseas Communist movements (Visscher, 1993). By the 1990s, these reforms helped to normalize relations with Indonesia and spurred the PRC’s rapid industrialization, export-led growth, and accession to the World Trade Organization. These changes helped to position Beijing as a credible partner when Indonesia sought to rebuild its economy following the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis.

Over the last three decades, Chinese and Indonesian leaders and cabinet officials have made numerous high-level visits to rebuild relations. By 2005, Indonesia and China elevated bilateral relations to a “strategic partnership,” later upgraded to a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” in 2013.[1] Indonesia joined the ASEAN[2]-China Free Trade Area in 2010, became a founding member of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB)[3] in 2015, and officially joined the PRC’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2017.

Even as Indonesian leaders pursue closer economic ties with Beijing, their enthusiasm is tempered by maritime disputes in the Natuna Sea (Nabbs-Keller, 2020; Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, 2024). Jakarta and Beijing have “overlapping claims” to the continental shelf and exclusive economic zone off the coast of Natuna Island (Darmawan, 2020 and 2024). Indonesia has reinforced its military presence in the Natuna Sea and lodged diplomatic protests (Nabbs-Keller, 2020). This initially firm stance was diluted when President Subianto and Chinese President Xi Jinping announced in November 2024 that the two countries would jointly develop the contested areas (Darmawan, 2024).

Economic and political elites, meanwhile, express concerns over competition from cheaper or lower quality Chinese goods[4] and overdependence on Chinese investment in strategic sectors such as nickel (Nabbs-Keller 2020; Sritharan and Rizkallah 2024). Over the last five years, leveraging Chinese investment and technology, Indonesia has positioned itself as a dominant power in nickel production, accounting for 63 percent of the world’s supply (Forbes, 2025). However, there is growing unease over the fact that China effectively controls three-quarters of Indonesia’s smelting operations (Reuters, 2025), critical to the production of stainless steel and electric vehicle (EV) batteries.[5]

President Subianto’s early state visits and speeches signal that the administration wants to double down on economic and security cooperation with China (Liu and Rayi 2024; Secretariat Cabinet of Indonesia, 2025).[6] However, Subianto is actively cultivating relationships with alternative players—from Russia and the United States to the Middle East and Turkey (King, 2025). Following his first trip to China, Subianto visited Washington, wanting to cooperate with both major powers (Reuters 2024).

1.2 Tracking Beijing’s economic statecraft in Indonesia

For thirteen consecutive years, the PRC has been Indonesia’s largest trading partner, a top destination for the archipelago’s exports, and a leading source of imported goods.[7] From a modest start of only US$1.18 billion in 1990, trade between the two countries surged to US$135 billion by 2024 (Chinese Embassy, 2004; Minister of Trade of Indonesia, 2025).

From 2000 to 2023, Indonesia attracted approximately US$69.6 billion in financing from the PRC for over 400 development projects. Following the 2008 global financial crisis, Beijing emerged as one of the leading sources of development finance to Indonesia.[8] These projects vary widely in size and scope, ranging from small-scale social initiatives and goodwill programs, such as support for schools and civil society organizations, to large-scale infrastructure ventures aimed at developing and capitalizing on Indonesia’s substantial nickel reserves.

Beyond trade and aid, China has become a go-to investment source for Indonesia in recent years. The Indonesian Statistics Agency (2025) reported US$8.1 billion in Chinese FDI across 21,464 projects in 2024 alone.[9] Over the past decade, China has invested a total of US$45 billion through 43,702 projects, primarily focused on critical physical and digital infrastructure sectors (e.g., energy, mining, construction, transportation, telecommunications).[10]

In Chapter 2, we follow the money to spotlight Beijing’s revealed priorities in what projects it finances, when, and where in Indonesia. We examine the PRC’s state-directed development finance to Indonesia across grants, loans, debt instruments, and technical assistance to public and private sector actors. This includes Official Development Assistance (ODA)—grants and concessional loans referred to as “aid”—and Other Official Flows (OOF), non-concessional loans and export credits referred to as “debt.” Second, we look at Chinese FDI, where PRC-based firms acquire at least a 10 percent equity stake in Indonesian enterprises, reflecting longer-term commercial interest and operational control.

We draw upon three primary sources for this analysis: (i) AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0, a project-level database of Chinese state-directed aid and debt financing from 2000 to 2021; (ii) supplemental desk research to identify provisional or announced projects post-2021; and (iii) inbound Chinese FDI data from the fDi Markets platform, a cross-border investment database maintained by Financial Times, Ltd, for 2010 to 2024.

Chapter 3 scrutinizes the relationships behind Beijing’s development finance investments: how many players there are, who they are, their roles, and whether some are more important than others. We analyze the supply side of these transactions to trace intricate cross-border networks of financiers, co-financiers, and implementers that bankroll and deliver PRC-financed development in Indonesia. Then, we assess the demand side: which communities, agencies, and organizations receive more and less of these investments, and why?

Without clear and compelling evidence, Indonesian policymakers, journalists, and the public are left in the dark about the long-term costs and benefits of partnering with opaque foreign state investors like the PRC. Chapter 4 assesses Beijing’s performance: to what extent does it follow through on its promised commitments, how does it manage the risk of public harm from its projects, and what early indications do we see of the downstream outcomes across societies?

This analysis draws upon a variety of third-party surveys and subnational data on economic, environmental, social, and governance indicators from reputable sources, including the Gallup World Poll, Varieties of Democracy, the World Bank, Indonesia’s Statistical Agency (BPS), and Asian Barometer, among others. We also incorporate insights from expert interviews conducted virtually by AidData and Foreign Policy Talks.[11]

Chapter 5 concludes with key takeaways arising from this research. A supplemental Technical Appendix provides additional information about the methods, assumptions, and data sources used in this research.

2. Money

Key insights in this chapter:

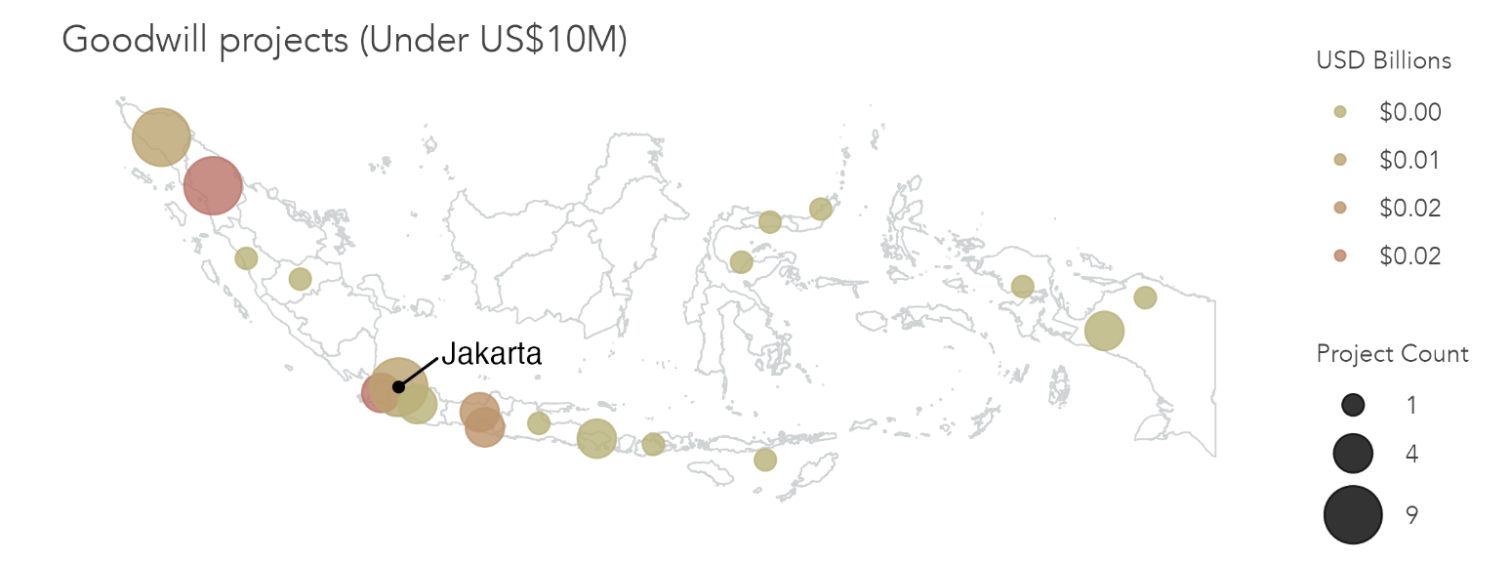

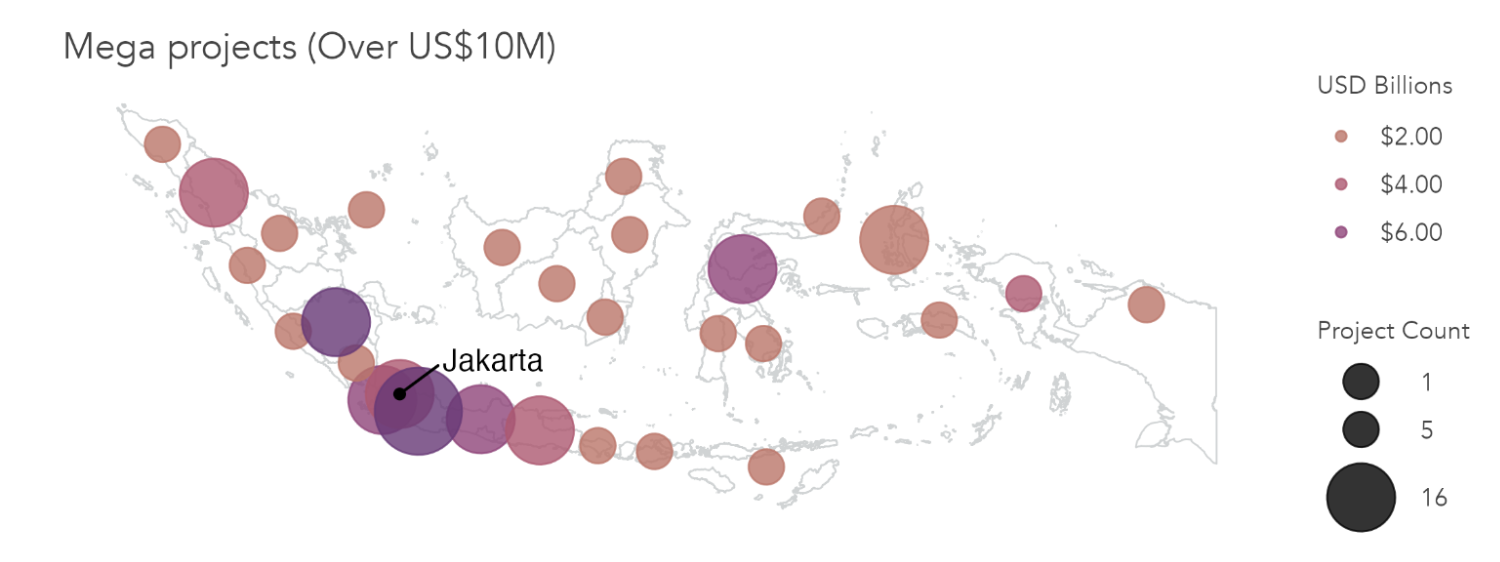

- Beijing employs a two-track model in Indonesia—it offsets a few risky, hard infrastructure big bets with many small-dollar social development projects

- Indonesia stands out from its Southeast Asian peers, attracting comparatively larger shares of Chinese development finance and foreign direct investment

- PRC-financed projects in energy, transport, and critical mineral processing sought commercial returns, blended public and private sector dollars, and aimed to advance BRI aspirations while responding to domestic political priorities

Over two decades, Chinese money has gone from a footnote to a headline in Indonesia’s economic growth trajectory. Government agencies, state-owned enterprises, and private companies from China have invested large sums in Indonesia’s roads, power plants, and factories. These financial infusions are erratic: big booms one year, sudden lulls the next. This chapter follows the money to uncover what Beijing’s state-directed development finance and private sector foreign direct investment reveal about the PRC’s strategic priorities.

In the remainder of this chapter, we analyze how the PRC’s engagement in Indonesia varies over time, relative to other donors and ASEAN peers (Section 2.1) and across five presidential administrations (Section 2.2). We investigate which regions and communities attract the most Chinese investment (Section 2.3) and how inbound Chinese FDI diverges or converges with Beijing’s state-directed development finance in sector and geography (Section 2.4).

2.1 How has the PRC’s development finance changed over time and relative to the alternatives?

Chinese development finance to Indonesia has expanded significantly over the past two decades, but its trajectory has not followed a straight line. Financial commitments have risen and fallen sharply across key political and economic junctures between the two countries, along with global uncertainties. This raises three questions worth exploring. How does Beijing’s development finance offer compare with the alternatives available to Indonesia? To what extent is Beijing’s economic engagement in Indonesia similar or unique to that observed in other ASEAN countries? And to what extent have Indonesia’s domestic policies and regulatory choices shaped—or constrained—the PRC development financing it receives? We consider each question in turn in the rest of this section.

2.1.1 How does Beijing compare with other development partners?

To contextualize its role relative to others, we benchmarked the PRC against six active development partners in Indonesia. This included the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the World Bank (WB), Australia, Japan, South Korea, and the United States (U.S.). Each of the six comparators reports its development finance by country, sector, flow type, and year to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Creditor Reporting System (CRS). Our analysis considers Official Development Assistance (i.e., grants and no- or low-interest loans, commonly referred to as “aid”) and Other Financial Flows (i.e., loans and export credits at market rates referred to as “debt”). We focus this discussion on commitments for comparability.

Between 2000 and 2023, Indonesia received an estimated US$69.6 billion in official development finance from the PRC, its largest bilateral financier (see Table 2.1). Beijing outspent the combined contributions of the four bilaterals:[12] Japan (US$29.3 billion), South Korea (US$15.7 billion), Australia (US$10.3 billion), and the United States (US$7.97 billion). The PRC’s development finance also eclipsed the two multilaterals: the WB (US$47.7 billion) and the ADB (US$36.6 billion).

2.1.1.1 Comparing the terms of Beijing’s assistance relative to others

Beijing operates less like a traditional aid donor and more like a commercial lender-developer. Over 90 percent of Beijing’s development finance is issued as debt (e.g., non-concessional loans and export credits), while only 3 percent is given as concessional (no- or low-interest) loans and grants. Access to Beijing’s financing is often tied to using Chinese contractors, procurement chains, or co-financing arrangements with Chinese firms. Moreover, the profile of Beijing’s assistance in Indonesia became less generous over the last two decades. Its portfolio is increasingly focused on commercially-oriented projects featuring loans to Indonesian businesses or special purpose vehicles (SPVs) (Gelpern et al., 2021).

Although it was also focused on infrastructure, Japan represents the opposite end of the generosity spectrum: 100 percent of its development finance was offered as grants or highly concessional loans.[13] Bilaterals like Australia and the U.S. also assisted Indonesia with highly concessional loans and grants, but they focused on social sector programs such as governance, education, and health. It is important to note that this analysis predates moves that the U.S. and several European donors have made to reduce aid budgets in 2024 and 2025 (Custer et al., 2025a and 2025b).

South Korea was more similar to the PRC in its prioritizing of commercially-tied loans for bankable projects (albeit at a smaller scale) over concessional finance in the social sector. It blends technical assistance from the Korea International Cooperation Agency with tied loans from the Economic Development Cooperation Fund, which supports Korean firms. The volume of South Korea’s assistance to Indonesia is modest, at half the size of Japan’s and less than a quarter of the PRC’s commitments. Its highest profile project was the Karian Serpong Water Supply Project (Susanty, 2017).

Indonesia’s middle-income status means that multilateral development banks like the ADB and WB tend to offer loan terms comparable to market rates, rather than the heavily discounted rates offered to other low-income countries. For example, a 331.3 million euro loan from ADB for programming in the health sector had a 12.5-year maturity and a seven-year grace period (ADB, 2023).[14] In the context of emergency response, multilaterals may use more generous terms. WB and ADB assistance in the wake of the 2018 Sulawesi earthquake and tsunami is a case in point: the two donors pledged US$1 billion with an extended repayment period (32 years) and slightly longer grace period (8 years) (Tang, 2018).

Comparatively, Beijing’s debt terms have been less generous on average than similar lending from the multilateral development banks. For projects where full loan details were available,[15] the average Chinese loan to Indonesia during this period carried an 8.6-year maturity and a 3.6-year grace period. There are exceptions to this rule, particularly in the context of competition with other development finance suppliers. Notably, PRC financing for the Jakarta–Bandung High Speed Rail Project featured more attractive terms than usual in response to a bidding war with Japan.[16] For that project, Beijing extended US$4.5 billion in loans at a 2 percent interest rate, with a 40-year maturity and 10-year grace period (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022). The project used a business-to-business scheme with a 50-year concession to operate the rail. This was later extended to 80 years due to cost overruns (Mahardhika and Wibawa, 2023).

Table 2.1: Total official finance commitments from major development partners to Indonesia, 2000-2023

The table can be sorted by clicking on a column. On small screens, scroll horizontally to view hidden columns.

|

Development partner |

Official Development Assistance (ODA) |

Other Official Flows (OOF) |

Vague (level of concessionality undetermined) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

China (Total: $69.6B; ODA 3%) |

2.08 |

64.93 |

2.61 |

|

Asian Development Bank (Total: $36.6B; ODA 4%) |

1.29 |

35.36 |

N/A |

|

Australia (Total: $10.3B; ODA 97%) |

10.03 |

0.27 |

N/A |

|

Japan (Total: $29.3B; ODA: 100%) |

29.34 |

0.00 |

N/A |

|

South Korea (Total: $15.7B; ODA: 14%) |

2.18 |

13.51 |

N/A |

|

United States (Total: $7.97B; ODA: 100%) |

7.97 |

0.01 |

N/A |

|

World Bank (Total: $47.7B; ODA: 0%) |

0.00 |

47.66 |

N/A |

Notes: All figures in billions of constant 2024 USD. The research team supplemented PRC finance data with limited desk research and media article reviews to identify additional projects and details for 2022 and 2023. Data for these additional years should be considered provisional. Sources: OECD CRS Database, 2000-2023 and AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0 for 2000-2021 (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022).

2.1.1.2 Comparing Beijing’s assistance trajectory relative to others

Beijing was not always as dominant a player in Indonesia’s development (see Figure 2.3). Before the 2008 global financial crisis, the PRC’s financing (US$7.3 billion) was on par with multilaterals like the ADB (US$6.9 billion) and the WB (US$5.3 billion) in commitments between 2000 and 2007. All three players were far surpassed by Indonesia’s lead development partner for most of these early years: Japan, which committed US$13.3 billion (Figure 2.3). Two early exceptions to this rule were in 2003 and 2006, when Chinese development finance temporarily surged, positioning Beijing as Indonesia’s largest donor in those years.

This status quo changed dramatically after 2008, as the PRC jumped ahead of the pack to become Indonesia’s single largest development finance supplier from 2011 to 2018. During the COVID-19 pandemic,[17] China’s development finance dropped off significantly, consistent with global trends in its lending. Multilateral development banks such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank assumed a more prominent role, allocating hundreds of millions in funding for health infrastructure strengthening (Figure 2.3).

As of 2023, Beijing’s development finance to Indonesia appeared to be on the upswing, based on a preliminary review of announced projects. The PRC announced an estimated US$4.2 billion of financing across 18 energy and industrial projects.[18] However, it remains to be seen whether Beijing will follow through on these plans. Notably, PowerChina’s initial announcement of its intention to fund the US$17.8 billion Kayan Cascade project turned out to be more hype than substance, as it subsequently withdrew from the project (Koswaraputra, 2024).[19]

Figure 2.2: Total official finance commitments from China to Indonesia, 2000-2023

Notes: All figures in billions of constant 2024 USD. The research team supplemented PRC finance data with limited desk research and media article reviews to identify additional projects and details for 2022 and 2023. Data for these additional years should be considered provisional. Sources: AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0 for 2000-2021 (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022)

Figure 2.3: Official finance commitments by year from major development partners to Indonesia, 2000-2023

Notes: The research team supplemented PRC finance data with limited desk research and media article reviews to identify additional projects and details for 2022 and 2023. Data for these additional years should be considered provisional. Sources: OECD CRS Database, 2000-2023 and AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0 for 2000-2021 (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022).

2.1.1.3 Comparing Beijing’s sectoral focus relative to others

Beijing’s development finance to Indonesia has consistently prioritized securing natural resources, expanding industrial capacity, and promoting physical and digital connectivity. Energy investments (US$20.12 billion, 56 projects) initially emphasized coal-fired power generation, later extending to hydropower. Industry, mining, and construction activities (US$17.44 billion, 65 projects) sought to reduce barriers to entry for Chinese companies to invest in Indonesia’s Special Economic Zones. Transport and storage was also a top sector, attracting US$9.38 billion across 37 projects, from high-speed rail to toll roads. Together, these three sectors alone account for over 70 percent of Beijing’s development finance dollars to Indonesia between 2000 and 2023 (Table 2.4).[20]

Table 2.4: Top 10 sectors of PRC-funded development projects in Indonesia, 2000-2023

By millions of USD |

By number of projects |

|||

Energy |

$20,122 |

Industry, mining, construction |

65 |

|

|

Industry, mining, construction |

$17,441 |

Energy |

56 |

|

|

Transport and storage |

$9,378 |

Emergency response |

47 |

|

Other multisector |

$5,837 |

Business and other services |

42 |

|

Communications |

$4,314 |

Transport and storage |

37 |

|

|

Unallocated / unspecified |

$1,888 |

Unallocated / unspecified |

32 |

|

|

Business and other services |

$1,614 |

Education |

28 |

|

|

Banking and financial services |

$1,029 |

Communications |

21 |

|

|

Agriculture, forestry, fishing |

$615 |

Health |

20 |

|

|

Trade policies and regulations |

$590 |

Action relating to debt |

16 |

Notes: This table shows the top 10 sectors of PRC-funded development projects from 2000 to 2023 (including aid and debt instruments) in millions of constant 2024 USD (left) and number of projects (right). The research team supplemented PRC finance data with limited desk research and media article reviews to identify additional projects and details for 2022 and 2023. Data for these additional years should be considered provisional. “Unallocated/unspecified” indicates insufficient detail to assign a sector to the project. Sources: AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0 for 2000-2021 (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022).

Globally, the PRC employs a two-track development model pairing big-ticket infrastructure investments with the expectation of commercial returns alongside small-dollar goodwill projects for reputational gains (Custer et al., 2025). This pattern is also evident in Beijing’s development finance in Indonesia. The Chinese government sent money, food, search and rescue support, and medical teams to aid Indonesia in response to natural disasters. This category of emergency response accounted for the third largest number of projects, though this was heavily concentrated around the December 2004 earthquake and subsequent tsunami.[21] Although it typically allocates fewer dollars than other development partners in these areas, Beijing also financed social sector activities in education (28 projects) and health (20 projects).

Beijing’s development finance is often associated with the idea of infrastructure, given the prominence of the Belt and Road Initiative. However, there are various facets of infrastructure relevant to a country’s growth and prosperity. In this report, we examine the extent to which Beijing (as compared to other development partners) helps Indonesia develop infrastructure in several areas:

- Economic and information infrastructure (i.e., banking and financial services; business services; telecommunications; economic infrastructure and services)

- Physical connectivity infrastructure (i.e., trade policies and regulations; transport and storage)

- Utilities, foods, and power infrastructure (i.e., agriculture, forestry, fishing; energy; industry, mining, construction; production sectors; water supply and sanitation)

- Social and environmental infrastructure (i.e., education; environmental protection; government and civil society; health; social infrastructure and services; population policies/programs; and reproductive health)

South Korea (92 percent), the PRC (76 percent), and Japan (56 percent) share a revealed preference in orienting most of their development finance dollars to hard infrastructure (e.g., physical connectivity; utilities, food and power). By contrast, Australia and the U.S. were much less active in the hard infrastructure sectors, instead directing over half (58 percent each) of their development finance portfolios to supporting Indonesia’s building of social and environmental infrastructure.

Table 2.5: Total official finance commitments from major development partners to Indonesia by sector, 2000-2023

The table can be sorted by clicking on a column. On small screens, scroll horizontally to view hidden columns.

|

Sector |

PRC |

Asian Development Bank |

Australia |

World Bank |

Japan |

South Korea |

United States |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Disaster risk reduction, emergency response |

0.08 |

0.00 |

0.36 |

0.28 |

0.61 |

0.02 |

1.42 |

|

Economic and information infrastructure |

6.96 |

5.68 |

0.12 |

6.65 |

0.08 |

0.55 |

0.15 |

|

Physical connectivity infrastructure |

9.97 |

1.75 |

0.79 |

3.31 |

7.81 |

1.92 |

0.15 |

|

Social and environmental infrastructure |

0.43 |

14.53 |

5.95 |

23.71 |

2.72 |

0.64 |

4.60 |

|

Utilities, food, and power infrastructure |

42.88 |

10.98 |

1.08 |

8.92 |

8.58 |

12.44 |

0.51 |

|

Other |

9.30 |

3.71 |

2.00 |

4.79 |

9.54 |

0.11 |

1.13 |

Notes: Commitments are denominated in billions of constant 2024 USD. Darker colors indicate higher volumes of financing from a particular donor in a given sector. The research team supplemented PRC finance data with limited desk research and media article reviews to identify additional projects and details for 2022 and 2023. Data for these additional years should be considered provisional. Sources: OECD CRS Database 2000-2023 and AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0 for 2000-2021 (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022).

Unsurprisingly, the U.S., historically the largest single supplier of humanitarian assistance globally (Custer et al., 2025), channeled a greater share of its portfolio (18 percent) to risk reduction and emergency response funds than other donors.

The two multilateral development banks fell somewhere in between. Hard infrastructure projects still accounted for a quarter to one-third of World Bank (WB) and Asian Development Bank (ADB) financing in Indonesia. Moreover, both institutions shared a common interest with the PRC in bankrolling projects in the economic and information space. That said, the WB (50 percent) and ADB (40 percent) were bigger players than the PRC in supporting Indonesia’s development of social and environmental infrastructure. The WB, for instance, committed US$23.71 billion to social and environmental infrastructure in Indonesia between 2002 and 2023, roughly 54 times China’s contribution, which amounted to US$430 million in the same sector.

As part of the COVID-19 rescue package, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) provided a US$1.5 billion loan to Indonesia.[22] The project was co-financed with the ADB and the WB as part of a broader COVID-19 support initiative. In total from 2020 to 2024, Indonesia received more than US$4.19 billion from AIIB, which was dispersed across varying sectors from energy, healthcare, to satellite communications.[23]

2.1.2 How do flows of Chinese development finance vary across ASEAN?

Among its ASEAN neighbors, Indonesia stands out as the top recipient of Beijing’s development finance dollars between 2000 and 2021. Beijing’s global interest in using development finance to open up new markets for Chinese firms likely informs its interest in Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest economy and an important hub for regional connectivity. The sectoral composition of Chinese development finance in the country’s transport, energy, and extractives sectors aligns with the PRC’s interests in securing energy and mineral resources. These areas also mirror Indonesia’s domestic development priorities.

Indonesia is the PRC’s flagship partner in advancing Beijing’s regional infrastructure ambitions under the BRI. The Jakarta–Bandung High-Speed Rail is ASEAN’s largest BRI project. Indonesia also hosts other PRC-backed projects in digital networks, ports, and extractives, as part of Beijing’s Digital Silk Road push to expand data infrastructure and e-commerce platforms across ASEAN (Rakhmat, 2022). These efforts are backed by financial instruments such as concessional and commercial loans from China Development Bank and China Eximbank.

More broadly, variation in the PRC’s development finance portfolio across the ASEAN region is likely shaped by a combination of factors. On the demand side, a country’s national development priorities and regulatory frameworks may make working with Beijing more or less attractive across ASEAN members. On the supply side, Beijing also considers the degree to which a prospective recipient is geostrategically important and diplomatically aligned with the PRC in its development finance allocations.

In mainland Southeast Asia, Laos (US$23.8 billion, 306 projects) and Cambodia (US$19.8 billion, 369 projects) are other prominent recipients of PRC development finance over two decades. Despite their smaller economies, both countries have maintained close political ties with Beijing and have been enthusiastic participants in the BRI framework. Their infrastructure portfolios include large-scale transport corridors, power generation, and hydropower assets, often financed through loans from Chinese state policy banks. These flows, while substantial, typically involve limited policy conditionality, distinguishing them from multilateral development financing alternatives.

Vietnam (US$32.4 billion, 178 projects) and Malaysia (US$17.9 billion, 162 projects) have taken a more selective and cautious approach to PRC development finance. Both countries have leveraged Chinese capital to finance strategic projects but have prioritized regulatory due diligence, often renegotiating terms to ensure alignment with domestic political and fiscal priorities. Vietnam was the second-largest recipient of Chinese projects in value. However, it lags behind its Mekong region peers in project implementation, due partly to Hanoi’s skepticism of closer ties to Beijing (Ha, 2022). Vietnam’s historical tensions with the PRC and ongoing maritime disputes in the South China Sea have contributed to a more cautious investment posture, particularly in politically sensitive sectors. Malaysia has similarly restructured major BRI projects, such as the East Coast Rail Link.

Comparatively, the Philippines and Thailand have received lower volumes of Chinese development finance: US$9.1 billion across 219 projects and US$5.8 billion over 99 projects, respectively. In the case of the Philippines, shifts in political leadership and foreign policy alignment have had a measurable effect on investment flows (Custer et al., 2024). Under President Rodrigo Duterte, closer diplomatic ties with Beijing led to an uptick in project approvals, though many remained slow to disburse (ibid). Thailand, a relatively mature middle-income economy with diversified investment sources, has maintained a more conservative portfolio of PRC-financed projects, supplementing rather than depending on Chinese capital.

Table 2.6: Total PRC development finance commitments to ASEAN countries, 2000-2021

Country |

Commitments (2024 USD) |

Project count |

|---|---|---|

Indonesia |

$61.7 billion |

400 |

Vietnam |

$32.4 billion |

178 |

Laos |

$23.8 billion |

306 |

Cambodia |

$19.8 billion |

369 |

Malaysia |

$17.9 billion |

162 |

Myanmar |

$16.3 billion |

444 |

Philippines |

$9.1 billion |

219 |

Thailand |

$5.8 billion |

99 |

Brunei Darussalam |

$2.4 billion |

51 |

Notes: Comparable Chinese development finance data is only available across countries through 2021, so the total value of PRC commitments to Indonesia is lower here than in the rest of the report, which covers through 2023. Source: AidData's Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0.

2.2 How has Beijing’s financing varied across administrations?

Beijing’s development financing to Indonesia has demonstrated distinct peaks and troughs across different presidential administrations—a gradual rise under Megawati Soekarnoputri (2000-2004), more erratic ups and downs during the tenure of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (2004-2014), and record-breaking highs under Joko Widodo’s first term (2014-2019), before tapering off during and following the COVID-19 pandemic (2019-2024) (Figure 2.2). The number of projects has similarly fluctuated substantially within and between administrations (Figure 2.7).

Taken together, these patterns highlight that Beijing’s development financing in Indonesia has not followed a simple upward trajectory. There have been periods of strategic expansion, as Beijing opportunistically sought to respond to the priorities of Indonesian political leaders, followed by noticeable recalibrations. Surges in projects and dollars sometimes corresponded with major diplomatic events such as state visits or bilateral summits, but not always. Nor did the PRC’s investments predictably rise with Indonesia’s chairmanship of ASEAN in 2011 and its hosting of the 18th and 19th summits.

The decline in the volume of China’s state-directed financing to Indonesia between 2019 and 2022 mirrors global trends AidData has observed in PRC investments, as Beijing pivoted to emphasize emergency financing for BRI countries facing difficulty serving debt obligations (Parks et al., 2023). Project counts have not seen as sharp a drop as dollars, which implies that Beijing may be shifting more of its efforts towards “small but beautiful” goodwill activities, while encouraging more private sector engagement, including from Hong Kong (Yeung, 2024).[24] This downward trend could reflect growing caution within Indonesia toward PRC financing, shifting domestic political priorities, and broader global concerns over debt sustainability.

Figure 2.7: PRC-funded development projects in Indonesia, 2000-2023

Notes: The research team supplemented PRC finance data with limited desk research and media article reviews to identify additional projects and details for 2022 and 2023. Data for these additional years should be considered provisional. Sources: AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0 for 2000-2021 (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022).

Table 2.8: Major trends in PRC-funded development projects by presidential administration in Indonesia

Administration |

Trend |

Example projects |

|---|---|---|

|

Megawati Soekarnoputri (2001-2004) |

Energy and infrastructure projects |

Tangguh Liquified Natural Gas and Suramadu Bridge |

|

Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, first term (2004-2009) |

Disaster relief and energy projects |

2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and 10.000 MW Fast Track Program I |

|

Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, second term (2009-2014) |

Diversification into critical industries, telecommunications, and private sector financing |

10.000 MW Fast Track Program II and Palapa Ring |

|

Joko Widodo, first term (2014-2019) |

Transport and infrastructure, energy, and state-owned enterprise financing |

Jakarta–Bandung High-Speed Rail |

|

Joko Widodo, second term (2019-2024) |

COVID-19 recovery and downstream-related industries and investments |

Morowali Industrial Park |

2.2.1 Abdurrahman Wahid (1999-2001)

Only a decade following the reestablishment of bilateral relations, Indonesian President Abdurrahman Wahid emphasized stability and reconciliation in his dealings with China. His administration laid the groundwork for normalizing Sino-Indonesian relations, removing restrictions for the Chinese-Indonesian community to observe religious, cultural, and linguistic traditions such as the Lunar New Year. He formally recognized Confucianism as an official religion and appointed Chinese-Indonesian economist Kwik Kian Gie as Coordinating Minister for the Economy, a meaningful gesture of inclusion. Direct economic engagement with Beijing was minimal, but Wahid’s policies created the conditions for more robust bilateral cooperation in the following years.

Despite serving only 21 months in office, President Wahid spent nearly a quarter of his tenure on state visits.[25] China was Wahid’s first visit in 1999, a signal of his desire to improve bilateral relations, which culminated in a Joint Communiqué.[26] The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis presented China with an opportunity to translate renewed diplomatic ties into tangible support, primarily channeled through multilateral rather than bilateral frameworks. As a goodwill gesture, Beijing contributed US$400 million in standby loans as part of the IMF’s rescue package for Indonesia, US$200 million in export credit facilities, a US$3 million grant in medicines, and 50,000 tons of rice.[27] This positioned China favorably in the eyes of Indonesia (Sukma, 2009). Otherwise, Beijing’s development finance during this period was limited, likely influenced by political sensitivities after the 1998 riots that disproportionately affected Chinese-Indonesians.

2.2.2 Megawati Soekarnoputri (2001-2004)

Assuming office following Wahid’s 2001 impeachment, President Megawati Soekarnoputri continued gradual normalization in Indonesia-China relations. Her administration formally recognized the Chinese New Year as a national holiday. Trade and investment between the two countries grew steadily, reaching US$8.7 billion in 2004,[28] comparable to Indonesia’s trade volume with the U.S. that year (Indonesian Statistics Agency, 2025). Beijing also sent humanitarian and disaster relief to Indonesia following the 2002 Bali Bombing, the Nabire earthquake, and an influenza outbreak, along with donated motorcycles for the Indonesian National Police in 2003. However, most of the PRC’s development finance (US$2.18 billion) was in the form of debt to support hard infrastructure projects with the expectation of commercial returns.[29]

President Megawati’s administration marked a shift in Beijing’s development finance from symbolic gestures to more strategic, sector-specific engagements. Financing was increasingly tied to long-term economic cooperation, particularly in energy and infrastructure. Although modest compared to the scale seen in later years, China’s financial support during this period (nearly US$2.2 billion) demonstrated a growing willingness to invest in Indonesia’s post-crisis recovery and development agenda.

Energy was the cornerstone of growing economic ties, driven partly by China’s increasing consumption needs. China was a net importer of oil products by 1993 and of crude oil by 1996. The China National Offshore Oil Corporation became the largest offshore oil producer in Indonesia, acquiring interests in five national oil and gas assets from the Repsol-YPF Group for US$585 million (Offshore Magazine, 2002).[30] Indonesian officials sought long-term energy export contracts, including direct talks with Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji (Tempo, 2002).

During President Megawati’s March 2002 state visit to Beijing, Chinese President Jiang Zemin pledged US$6 million in grants and US$400 million in soft loans[31] to Indonesia, earmarked for railway development in East and West Java (Liputan 6, 2002) and signed a cooperation agreement between Pertamina and PetroChina, the largest oil and gas companies from each country (Weaver, 2002). The visit paved the way for the inaugural Indonesia-China Energy Forum in 2002. A key outcome of the forum was a landmark US$8.5 billion, 25-year contract to export liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Indonesia’s Tangguh block to China’s Fujian Province (People’s Daily, 2002).[32]

Indonesia’s Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources at the time hailed the LNG agreement as “the biggest project since the New Order era,” underscoring its importance for Indonesia’s post-crisis economic recovery (People’s Daily, 2002). Subsequent administrations criticized and sought to renegotiate the LNG deal, which was considered disadvantageous to Indonesia (Oster, 2006; Detik, 2008; Cahyafitri, 2014; MEMR, 2014). President Megawati defended the agreement, arguing that it opened the door to greater Chinese investment in Indonesia’s infrastructure and domestic processing capacity.

Beijing financed a second signature infrastructure project, the Surabaya–Madura (Suramadu) Bridge, with US$575.5 million via two preferential buyer’s credit loans from China Eximbank. Costing an estimated Rp 4.5 trillion (roughly US$466.6 million at current dollar rates) and spanning 5,400 meters, the Suramadu Bridge was among the most ambitious infrastructure projects of its time and a milestone in Indonesia-China relations. The project aligned closely with Indonesia’s broader national development goals, particularly around inter-island connectivity (The Jakarta Post, 2009).

2.2.3 Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (2004-2014)

Less than two months after President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was sworn into office in 2004, a massive 9.3-magnitude earthquake and tsunami hit Aceh and Nias in Northern Sumatra. Relief operations were complicated, as concerns were raised over the presence of foreigners in Aceh, a conflict zone where the Indonesian military had sought to quell a separatist movement (Fox News, 2005). Nevertheless, President Yudhoyono welcomed international assistance, which he later credited with facilitating a peace agreement that ended the 30-year conflict (Yudhoyono, 2025).

China initially provided US$2.6 million to tsunami-affected countries. Prime Minister Wen Jiabao subsequently pledged US$60 million in relief and reconstruction aid for ASEAN countries.[33] During his state visit to Jakarta, Chinese President Hu Jintao elevated bilateral relations with Indonesia to a strategic partnership (Qin, 2005), pledging an additional US$3.63 million in aid, along with US$300 million in loans to support infrastructure development and the reconstruction of areas affected by the tsunami disaster (China Daily, 2005).[34][35] China also supplied disaster relief to support Indonesia’s response to a series of earthquakes in Alor (2004), Nabire (2005), and Yogyakarta (2006).

Cooperation between China and Indonesia extended beyond the initial relief and reconstruction focus to encompass a deepening of economic ties between Presidents Hu and Yudhoyono. Bilateral trade expanded, moving from raw material exports toward investment in Indonesia’s capacity to domestically process its natural resources. The shift was described as a “honeymoon” phase (The Jakarta Post, 2008). Yudhoyono’s tenure saw a noticeable increase in Chinese loans directed to Indonesia’s private sector. Recipients ranged from large-scale mining corporations to consumer goods companies.

While development finance from Beijing lagged behind Seoul and Tokyo, China’s capital was directed toward several of Indonesia’s strategic priorities (The Jakarta Post, 2008), where there was implicit openness to foreign investment. For example, the Yudhoyono government had identified industrial development, transportation infrastructure, and telecommunications as essential facets of its roadmap for national growth over a 20-year time horizon.[36] Aligned with this, most of Beijing’s development finance during Yudhoyono’s tenure was directed to the energy and industrial sectors. These investments aligned with Indonesia’s urgent infrastructure development priorities, such as the transition from oil- to coal-fired power plants, to help Indonesia’s state-owned utility, Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN), overcome supply chain bottlenecks and high financing costs (Sambodo and Oyama, 2010; Ali and Wulandari, 2008).[37]

Beginning in 2006, President Yudhoyono signed several Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) on energy projects worth US$3.56 billion during the Indonesia-China Energy Forum in Shanghai (Detik, 2006; Antara, 2006).[38] The centerpiece of Yudhoyono’s energy policy was his 10.000 MW Fast Track Program (FTP) to rapidly increase domestic electricity supply.[39] The plan called for the construction of 10 new power plants in Java (7.430 MW) and 25 outside Java (2.121 MW), at an estimated cost of Rp 98.1 trillion.[40] PLN financed 15 percent of the project, with the remaining 85 percent sourced from foreign loans (MEMR, 2008).

Beijing was a fast mover, committing big money to support several projects in the first phase of the Fast Track Program. A reported 22 projects were awarded to Chinese companies, with nearly 90 percent of the project financing sourced from China (Detik, 2009; Kompas, 2009). President Yudhoyono announced a further US$761 million[41] in Chinese financing commitments for energy projects led by PLN in 2009, during an inauguration ceremony for the Suramadu Bridge. This included US$468 million[42] from China Development Bank for the Adipala power plant in Cilacap, Central Java, and US$293 million[43] from the Export-Import Bank of China for the Pacitan plant in East Java (Alfian, 2009).

Energy, particularly hydropower, would remain a focus of Indonesia-China collaboration in Yudhoyono’s second term, which secured US$3.6 billion in Chinese financing across 10 projects. The largest was a US$883 million buyer’s loan[44] for the second expansion of the 660 MW Cilacap Power Plant. Three of the nine power plants financed were part of phase two of Yudhoyono’s Fast Track Program, which aimed to rapidly expand the nation’s electricity generation capacity. This included the 110 MW Jatigede Hydropower Dam, backed by a US$147.6 million loan from China Eximbank.[45] Funding was distributed to projects across Indonesia, with several serving specific industrial needs as captive power sources (e.g., the Sulawesi Mining Power Station Project in the Morowali Industrial Park) or private sector projects under the Independent Power Producer scheme.

Projects related to refining and processing facilities—from establishing smelters and paper factories to expanding palm oil production—gained traction by Yudhoyono’s second term. Most financing was directed toward private sector entities to support business growth. A notable example is in 2013, when China Development Bank (CDB) provided a US$2.3 billion loan to PT OKI Pulp and Paper Mills, a subsidiary of Asia Pulp and Paper, for the construction of one of Indonesia’s largest paper mills (Antara, 2013).[46] The loan agreement was one of nearly two dozen signed during President Xi’s 2013 state visit to Indonesia,[47] collectively worth US$28.2 billion.[48] These cooperative agreements spanned critical minerals processing, transportation, telecommunications, training and capacity building, aviation, banking, and plantation development.

Digital connectivity was another recurring theme of China’s investments during Yudhoyono’s tenure. Buyer’s credit facilities—lending to finance the acquisition of equipment and services from Chinese companies such as ZTE and Huawei—was a popular modality for Beijing’s investments in Indonesian firms such as Axis, PT Smart Telecom, PT Indosat, and Telekom Indonesia. This telecommunications emphasis was also responsive to a presidential priority, as the sector’s development featured prominently in Yudhoyono’s national budget plans and commitment to see all Indonesian villages connected to the internet by 2010. His administration launched key connectivity programs such as Desa Internet (Internet Village), Desa Berdering (Ringing Village), and Palapa Ring. These projects blended domestic private and public finance, with sizable sums bankrolled by China, along with implementation by private and state-owned telecommunications companies.

Following the success of the Suramadu Bridge (see Box 1 above), this period also saw increased investment in more diversified transport and logistical infrastructure projects, including toll roads, railways, and bridges. There was also a significant uptick in business loans, with 36 separate instances amounting to nearly US$1 billion.[49] Merpati Airlines, established to serve Indonesia’s most remote regions, received one such loan to facilitate the purchase of 15 MA60 aircraft from China’s Xi'an Aircraft Industrial Corporation. However, the company experienced difficulty repaying the loan, eventually filing for bankruptcy in 2014.

China-Indonesia relations were at a relative high point during Yudhoyono’s tenure, with the inauguration of the Suramadu bridge, along with the spate of financing for energy, connectivity, and industrial development. In a landmark moment, during his 2013 state visit, President Xi addressed the Indonesian parliament, where he announced plans to build the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and the signing of the China-Indonesia Comprehensive Strategic Partnership. In line with its two-track development model of pairing big-ticket infrastructure projects with small-dollar goodwill efforts, Beijing provided in-kind support and financing for Mandarin language courses, Confucius Institutes across six universities in Indonesia, and scholarships for Indonesian students to study abroad in China.

However, Chinese development finance was not without controversy. Signs of strain emerged over disbursement delays, which triggered setbacks in project implementation,[50] while some cabinet officials raised concerns that China’s dollar-denominated loans could increase foreign exchange costs and create an onerous financial burden for Indonesia to repay.[51] Beijing-backed energy projects (e.g., Parit Baru Power Plant Project, Celukan Bawang Coal-Fired Power Plant) were scrutinized over labor and environmental concerns. A syndicated loan for Krakatau Steel was beset with delays and cost overruns before it was ultimately deemed economically unviable and closed a mere six months after construction was completed (Pratama, 2022). This led to the arrest of senior executives[52] and state losses amounting to Rp 6.9 trillion (Tempo, 2022).[53]

2.2.4 Joko Widodo (2014-2024)

Assuming office in 2014, President Joko Widodo inherited a relationship with China that was on the rise. The previous year, the two countries had signed a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, and Chinese President Xi Jinping chose Jakarta to launch the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. However, this cooperation was tempered by frequent maritime disputes between the two countries over fishing rights near the Natuna Islands (Lalisang and Candra, 2020). Widodo was pragmatic in his approach to Beijing, viewing China as a useful partner in helping Indonesia advance its national development and economic growth. Positioning Indonesia as a central node in global maritime trade and security was the cornerstone of Widodo’s foreign policy agenda, which he coined the “Global Maritime Fulcrum” (GMF).

The Widodo administration made infrastructure development—including an integrated mass public transportation system across sea, air, and land—a featured element of the president’s nine-point agenda known as the NawaCita.[54] Indonesia and China signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in 2018, formalizing maritime and logistics infrastructure cooperation. The MoU combined elements of BRI and GMF to enhance Indonesia’s inter-island and regional connectivity, drive economic growth, and meet rising domestic demand while hedging risk.[55] In several respects, the agreement attempted to mitigate concerns over indebtedness and dependence that had plagued Beijing’s BRI projects elsewhere (Bisnis.com, 2019; Cheang, 2019b).

Chinese development finance reached record levels in the number of projects (233) and dollars (US$40.3 billion) to help resource President Widodo’s ambitious infrastructure agenda. Notably, these investments were heavily concentrated during Widodo’s first term and were more frequently financed using debt-like instruments rather than conventional aid. The early years of Widodo’s presidency saw the return of large-scale Chinese energy investments in Indonesia.

Under his NawaCita agenda, President Widodo sought to install an additional 35,000 MW of electricity generation capacity across 210 locations over five years to meet growing demand.[56] Most of Beijing’s energy-focused development finance was oriented toward three projects, each exceeding US$1 billion in investment: (1) the 1,000 MW Cilacap Power Plant Phase 3 Expansion; (2) the 1,200 MW Bangko Tengah Mine-Mouth Power Plant; and (3) the 2,100 MW Java-7 Coal-Fired Power Plant. A smaller portion of Chinese financing was directed toward geothermal and gas projects, though these remained on a more limited scale.

The transport and logistics sector also attracted ample attention from Beijing, with the majority of financing directed toward the Jakarta–Bandung High-Speed Rail Project (HSR), the first of its kind in Indonesia and Southeast Asia (see Box 3 below).[57] The project triggered competing proposals from Japan and the PRC before Indonesia ultimately chose Beijing’s proposal, funded by the China Development Bank through a 75 percent debt and 25 percent equity structure (Brummitt and Chatterjee, 2015). Other PRC-financed transport investments included 16 toll road projects (US$2.45 billion), four railway projects (US$414.1 million), and the leasing of two 737-800 jets by BOC Aviation Limited to PT Lion Mentari Airlines.

Under the Widodo administration, and much like in its dealings with President Yudhyono, Beijing continued to direct a substantial portion of its development finance to projects in the industry, mining, and construction sector (US$6.5 billion). Critical minerals were a priority, aligning with Beijing’s hunger for natural resources and Jakarta’s interest in capturing more added value from these exports. Notable projects included a US$1.26 billion loan for the Xiamen Xiangyu Integrated Stainless Steel Plant Project in South Sulawesi and financing related to projects based in the Morowali Industrial Park, including smelters, steel plants, and captive coal power plants across four phases worth US$ 2.8 billion in total (see Box 3 below). Other projects focused on processing lithium and cobalt, but some also went to basic materials such as cement.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the PRC’s development finance to Indonesia was primarily focused on supporting the country’s response efforts, from personal protective equipment (PPE) and vaccines to liquid oxygen and other medical supplies worth roughly US$85 million. Beijing also supplied a capital injection to Bank Rakyat Indonesia in October 2020, allowing it to restructure more than 2.9 million debtors, with a total loan value of Rp190 trillion (Sidik, 2020).

With just a few months into Prabowo Subianto’s presidency, we can only make educated guesses as to how the PRC’s development finance might evolve. The Subianto administration has set out an ambitious goal of 8 percent growth for Indonesia and views Beijing as a crucial economic partner (Cabinet Secretariat of Indonesia, 2025). Chinese officials warmly characterized Indonesia as a model partner in the Global South and vital to China’s industrial value chains (Liu and Rayi, 2024). Indonesia was the first in Southeast Asia to join the BRICS+[58] as of January 2025, a hedge against uncertainty over U.S. tariff policies (King, 2025).

Rather than a full embrace of China, Subianto’s approach appears to build upon the foreign policy of his predecessor, Joko Widodo, who practiced “pragmatic equidistance” (Laksmana, 2017), balancing relationships with competing powers without aligning fully with either side in order to reap economic benefits but with diplomatic autonomy. This is not a new idea. Indonesia was an early leader of the non-aligned movement, promoting collective self-reliance and solidarity of developing countries to pursue shared economic goals (Pedersen, 2021). Beijing has sought to burnish its status as a developing country to ingratiate itself with other emerging economies like Indonesia (Strangio, 2025).

2.3 In which communities is China investing—and why?

In this section, we explore whether and how PRC development finance may vary in another respect: geography. To answer this question, we draw upon the location information in AidData’s project-level data on Chinese development finance to identify the subnational distribution of Beijing’s activities within Indonesia across 36 provinces and two special regions for Jakarta and Yogyakarta (the first-level administrative division). Between 2000 and 2023,[59] Beijing bankrolled activities across both large and small provinces. While PRC actors directed the most money to highly populated areas on Java and Sumatra, they also financed projects in more sparsely populated provinces such as West Papua to access strategically important minerals or waterways.

Java attracted the lion’s share of Beijing’s development finance that could be traced to the subnational level, in terms of both financial commitments (47 percent) and projects bankrolled (43 percent).[60] These activities were relatively equally spread across the island’s four administrative regions and two special capital regions: West Java (US$6.58 billion, 24 projects), Central Java (US$5.56 billion, 12 projects), Banten ($4.28 billion, 22 projects), the Jakarta Special Capital Region (US$3.53 billion, 21 projects), and East Java (US$3.42 billion, 22 projects). The notable exception was the Yogyakarta Special Region, which only received US$10 million, though its five projects still indicate a moderate amount of diplomatic outreach. Figure 2.9 and Table 2.10 below disaggregate projects across Indonesia’s provinces.

Economically dynamic and populous, Java represents attractive market opportunities for Chinese firms. Proximate to the historical seat of government and the home regions of Indonesia’s presidents, these geographies also provide an opportunity for the PRC to exert political influence with local elites.[61] Beijing’s economic engagement in Java illustrates its two-track development model. It financed expensive, commercially oriented projects, such as the Jakarta–Bandung High Speed Rail. In parallel, it also bankrolled relatively cheap goodwill projects in the social sector to win hearts and minds and build “people-to-people” ties. For example, Beijing oriented much of its support for Indonesia’s COVID-19 response (e.g., medical teams, donated medical supplies, and vaccines) to Jakarta and the surrounding areas.

Home to several large metropolises,[62] Sumatra attracted the second largest concentration of activity, receiving roughly one-quarter of Beijing’s development finance dollars and projects across its 10 provinces. South Sumatra captured relatively more money: Beijing directed over US$7 billion to the region, nearly US$800 per province resident. Much of this financing was oriented around a few big-ticket infrastructure projects related to paper pulp production, telecommunications, and power plants. Comparatively, North Sumatra and Aceh received a higher share of PRC projects, but with ostensibly lower dollar values.

Although Papua accounted for a relatively small share of Beijing’s development finance dollars and projects in absolute terms, the picture changes dramatically if we consider per capita investment. West Papua is a case in point: the province attracted only five projects worth US$3.69 billion during the period; however, this represents over three thousand dollars in per capita spending by Beijing to the resource-rich area. PRC investments focused on tapping West Papua’s natural gas reserves through a series of projects dating back to a 2006 investment by a consortium of Chinese banks[63] in the Tangguh Liquified Natural Gas Project.

Figure 2.9: Chinese-funded development projects in Indonesia by province, 2000-2023

Notes: These maps show total counts and dollar values for PRC-funded development projects in Indonesia aggregated to the province level. Multiple PRC projects could not be linked to a region, either because the project was national in nature or there was insufficient information to determine the precise location. The research team supplemented PRC finance data with limited desk research and media article reviews to identify additional projects and details for 2022 and 2023. Data for these additional years should be considered provisional. Sources: AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0 for 2000-2021 (Custer et al., 2023; Dreher et al., 2022).

Chinese official entities invested over US$3 billion into exploring and exploiting the offshore oil fields in resource-rich areas off Berau Gulf. The Tangguh gas field attracted a renewed round of investment in 2016, when the Bank of China and China Construction Bank invested US$415.6 million in the third wave of expansion. China’s growing appetite for energy and raw materials fueled interest in investments to build Indonesia’s liquefied natural gas export capacity; however, these projects are better understood as multinational ventures, rather than exclusively Chinese. Japan International Finance Management Corporation was the direct receiving agency for the 2016 wave of investment, and PRC-affiliated entities crowded in syndicated financing from Brazilian, Chinese, and Japanese banks. By contrast, Beijing paid negligible attention to other provinces in Papua, such as Maluku, Kalimantan, and Nusa Tenggara.

Sulawesi was in the middle of the pack as a destination for PRC development finance. Its six provinces attracted 17 percent of Beijing’s money and 12 percent of its funded projects. However, the spread of this attention was far from even. Central Sulawesi province accounted for most of Beijing’s portfolio in the region (US$5.76 billion, 15 projects), emphasizing export capacity for industrial goods. The PRC-backed Morowali Industrial Park was a cornerstone of this investment portfolio, with a consortium of Chinese lenders bankrolling the Sulawesi Mining Power Station Project to the tune of US$2.5 billion from 2013 to 2018. These investments sought to build the steel and nickel production capacity of smelters in the industrial park, and by extension, build the industrial base of Indonesia’s largest nickel-producing industrial site (see Box 4 above).

Table 2.10: Official PRC projects in Indonesia by province, 2000-2023

The table can be sorted by clicking on a column. On small screens, scroll horizontally to view hidden columns.

|

Province name |

Region |

Project value in billions of 2024 USD |

Project count |

Per capita USD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aceh |

Sumatra |

0.23 |

12 |

42.20 |

|

Bali |

Nusa Tenggara |

0.60 |

7 |

135.07 |

|

Bangka Belitung Islands |

Sumatra |

0.00 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

Banten |

Java |

4.28 |

22 |

344.05 |

|

Bengkulu |

Sumatra |

0.36 |

3 |

168.86 |

|

Central Java |

Java |

5.56 |

12 |

146.75 |

|

Central Kalimantan |

Kalimantan |

0.03 |

1 |

11.01 |

|

Central Papua |

Papua |

0.00 |

2 |

Missing population data |

|

Central Sulawesi |

Sulawesi |

5.76 |

15 |

1,844.92 |

|

East Java |

Java |

3.42 |

22 |

81.90 |

|

East Kalimantan |

Kalimantan |

0.27 |

5 |

66.51 |

|

East Nusa Tenggara |

Nusa Tenggara |

0.02 |

2 |

4.28 |

|

Gorontalo |

Sulawesi |

0.00 |

1 |

1.30 |

|

Highland Papua |

Papua |

0.00 |

0 |

Missing population data |

|

Jakarta Special Capital Region |

Java |

3.53 |

21 |

330.54 |

|

Jambi |

Sumatra |

0.00 |

1 |

0.43 |

|

Lampung |

Sumatra |

0.03 |

2 |

3.24 |

|

Maluku |

Maluku Islands |

0.02 |

1 |

12.38 |

|

North Kalimantan |

Kalimantan |

0.02 |

1 |

21.32 |