Aid in the National Interest: How America’s Comparators Structure their Development Assistance

Gates Forum II Background Research

Divya Mathew and Samantha Custer[1]

AidData | Global Research Institute | William & Mary

November, 2023

Executive Summary

In this paper, we examined how the U.S. and ten comparator countries organize and deploy development assistance to advance multiple objectives: humanitarian, economic, security, and geostrategic. We used a global survey to assess how leaders in low- and middle-income countries weigh the value proposition of these donors in a crowded aid marketplace. We summarize three lessons from this analysis for the U.S. to consider as it optimizes its development assistance in the future.

Level the Playing Field: Aid Can Achieve Mutual Benefits and Shared Goals. Donors juggle multiple interests—influenced by their geostrategic position, global norms, and domestic factors, from public support to electoral politics. From West to East, donors think about how aid can open markets, access resources, cultivate influence, curb migration, counter instability, and contain competitors. Donors from Portugal and Germany to the UK and Japan have taken a cue from South-South Cooperation providers like China and India, arguing that aid should advance shared goals to the mutual benefit of their partners. Donors increasingly grapple with articulating their value proposition to stand out in a competitive global landscape. Being forthright about aid and the national interest can level the playing field to work with Global South counterparts as equal partners in a shared enterprise.

Scavenge the Field for Inspiration, and Don’t Be Afraid to Learn from Smaller Players. China and the U.S. are large and fragmented development assistance suppliers, replete with coordination and coherence challenges. No single donor has divined a perfect solution to optimize assistance. Still, smaller players offer innovations that could be adapted and replicated in the U.S. France and Japan have experimented with top-down mechanisms facilitating interagency coordination in targeting aid to advance strategic objectives buoyed by high-level political leadership. Conversely, Portugal has emphasized coordination from the bottom up by establishing dedicated cooperation centers within its priority countries that serve as a clearinghouse for multiple agencies to integrate their assistance as a coherent offer to counterpart leaders. In a constrained budget environment, donors’ use of loans is on the rise—Germany, Portugal, and Japan expand the reach of their financing by supplying loans at concessional rates alongside grants.

Focus Resources on the Sweet Spot Between the Donors’ and Partners’ Interests. Influential donors tended to be big spenders, like the U.S., China, and the UK. But money was not deterministic: smaller players like Portugal have outsized influence with Global South leaders, while France and Australia punched below their weight. Some donors reaped benefits from focusing resources in geographies or sectors aligned with their interests: South Asia (India), East Asia and Pacific (Japan), Sub-Saharan Africa (Portugal), governance (Germany), and environment (Norway). Top influencers, like the U.S., were often seen as the most helpful in implementing reforms, but that was not true for others like China. One of the biggest predictors of influence and helpfulness was the degree to which donors were seen as aligned with the priorities of their partners—the most pressing development problems they wanted to solve.

This paper aims to answer three critical questions:

- How do bilateral donors articulate the aims of development assistance efforts in light of their respective national interests?

- In what ways do bilateral donors converge and diverge in how they organize, coordinate, and allocate development assistance to advance their national interests?

- What might the U.S. learn from other donors in strengthening its ability to deploy development assistance in ways that advance its national interests?

BRI: Belt and Road Initiative

BRICS: Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa

GNI: Gross National Income

KfW: Kreditanstalt fur Wiederaufbau

MOFCOM: Chinese Ministry of Commerce

NGO: Non-Government Organization

OECD: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

ODA: Official Development Assistance

OOF: Other Official Flows

PRC: People’s Republic of China

UK: United Kingdom

UN: United Nations

U.S.: United States

2. Aims: How America’s Comparators Rationalize Their Assistance

2.1 In the Club: Measuring Motivations of Development Assistance Committee Providers

2.2 Outside of the Club: From Recipients to Suppliers of Development Assistance

3. Architecture: How America’s Comparators Operationalize Their Assistance

3.1 Number of Players: Fragmentation Versus Consolidation

3.2 Positioning of Development Assistance: Degree of Integration and Coordination

4. Focus: How America’s Comparators Prioritize Their Assistance

4.1 The Bottom Line: Volume, Generosity, and Terms of Financing for Development

4.2 Channel of Choice: Giving Bilaterally or via Multilateral Channels

4.3 Where does the money go?: Geographic Focus

5. Performance: How Partner Countries Assess Their Development Partners

5.2 Influence: Who do developing country leaders listen to most in setting policy priorities?

5.3 Helpfulness: Who do developing country leaders turn to to help advance reforms?

1. Introduction

Sending money and expertise to aid people in faraway places is a hard sell to taxpayers in times of stability and strength. In a world characterized by widespread conflict, economic uncertainty, and environmental disasters, even the most altruistic political leaders have a tough case to make to their citizens that foreign aid is a good idea. Development assistance budgets have recently faced cuts across donors, including, but not limited to, Nordic countries renowned for their generosity (Lowery, T., 2022). The need to justify development assistance has prompted some donor countries to be more explicit in talking about how aid works in the national interest, to reorganize their programs to be responsive to that interest, and to look beyond aid (Nargund, 2023; Loy, 2023; Gulrajani & Calleja, 2021).

Aid in the national interest is not a new idea. In the United States, the term did not originate with President Donald Trump’s argument that his foreign policy would put “America First.” In his essay, Foreign Aid and the National Interest, Packenham (1966) cited empirical evidence to demonstrate that American officials saw aid as an “instrument of foreign policy” and “national interest was therefore a proper guide to aid decisions.” The U.S. is not unique in that position. Two decades later, Bill Hayden, Australia’s Foreign Minister, stated that “aid is not somehow tainted because, among other things, it helps serve our economic interests” (Hill, 2023). President Xi Jinping has framed his country’s overseas assistance as advancing the interests of both the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and its partners to their “mutual benefit” (PRC, 2021).

It is one thing to say that aid is in the national interest, but how do countries put these interests into practice via their foreign aid programs, and to what end? This paper examines how ten bilateral suppliers rationalize, structure, coordinate, and allocate development assistance to advance their respective national interests. We assess how these bilateral donors perform in the eyes of counterpart nations and derive insights for the United States to consider as it looks to strengthen its development assistance in the future. The ten comparator countries are Australia, PRC, France, Germany, Japan, India, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, and the United Kingdom (UK). We focus on trends and changes among these donors occurring over the last ten years, with some exceptions based on data availability, noting consequential events that predate this period when relevant.

The comparator countries represent different donor contexts that could be instructive for the U.S., varying on several key attributes that we will examine in the rest of this paper. We employ a mixed methods approach to draw insights from multiple sources: (i) in-depth background interviews conducted with policymakers and practitioners; (ii) desk research on comparative development assistance strategies, policies, and practices; and (iii) quantitative data on both the supply of and demand for, development assistance from these donors as collected by AidData and reputable third-party data providers.

|

Note on Terminology: In this paper, we examine how states employ grants, loans, and other debt instruments, along with in-kind and technical assistance to support development in other countries. This scope includes both Official Development Assistance (ODA) (i.e., grants and no- or low-interest loans typically referred to as 'aid') and Other Official Flows (OOF) (i.e., loans and other debt instruments approaching market rates referred to as 'debt'). We include in our assessment financing channeled by states via bilateral or multilateral mechanisms and humanitarian and long-term development assistance. We exclude military aid from this discussion. For ease of reading, we have chosen to simplify our terminology and use the generic terms “development assistance” and “aid” as catchalls for these various and diverse instruments. However, in instances where the particular modality matters (i.e., grants versus loans), we use the more specific terms to avoid confusion. |

2. Aims: How America’s Comparators Rationalize Their Assistance

For as long as states have maintained overseas development assistance programs, scholars have attempted to explain the motivations behind why policymakers are willing to send money and expertise abroad to help foreign leaders deliver peace and prosperity for their countries (Pedersen, 2021). Some scholars emphasize political or geostrategic rationales for development assistance—from a narrow quid pro quo to motivate the recipient to act in the donor's interests to a broader bid to build prestige that helps win friends and allies. Others argue that economic interests, such as securing critical materials or cultivating trading partners, play as much or more of a role in motivating donors to provide aid. Another school of thought points to a moral or humanitarian imperative for wealthier countries to assist an act of solidarity to assist countries in need.

Aid in the national interest is not a binary proposition. At least in their stated rhetoric, donors have mixed or multiple interests that they hold in tension. These interests can manifest differently over time, based on the donor’s perceived geostrategic position in the world, evolving global norms, and domestic factors from public support to party platforms and electoral politics (Bermeo, 2017; Gulrajani & Calleja, 2021). This state of play is echoed in our analysis of U.S. aid policy, legislation, and funding from the Cold War to the present day in Chapter 1.

In this paper, we argue that it may be more useful to envision aid in the national interest as a continuum between pure selfishness and absolute altruism, but with many stops along the way:

Parochial Self-Interest → Geostrategic Self-interest → Enlightened Self-Interest

- Parochial Self-Interest: The donor targets aid to derive immediate material benefits such as tying aid to domestic industry, export markets, and access to critical imports

- Geostrategic Self-Interest: The donor targets aid to bolster its reputation or undermine a competitor, providing indirect future leverage but not a direct material benefit

- Enlightened Self-Interest: The donor deploys aid to pursue goals that directly benefit someone else but also have the potential to help themselves in the distant future (e.g., promoting peace and prosperity abroad ensures peace and prosperity at home)

2.1 In the Club: Measuring Motivations of Development Assistance Committee Providers

In this section, we look at the U.S. and eight other member countries of the Development Assistance Committee—the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s club of the 32 largest providers of foreign aid that agree to adhere to a standard set of cooperation principles, policies, and reporting standards. India and the PRC are not member countries and are covered separately in section 2.2. To aid our comparison, we summarize what each of these nine Development Assistance Committee donors says they are trying to achieve (stated objectives) and contrast this with their underlying motivations (revealed objectives) by examining how they spend their money.

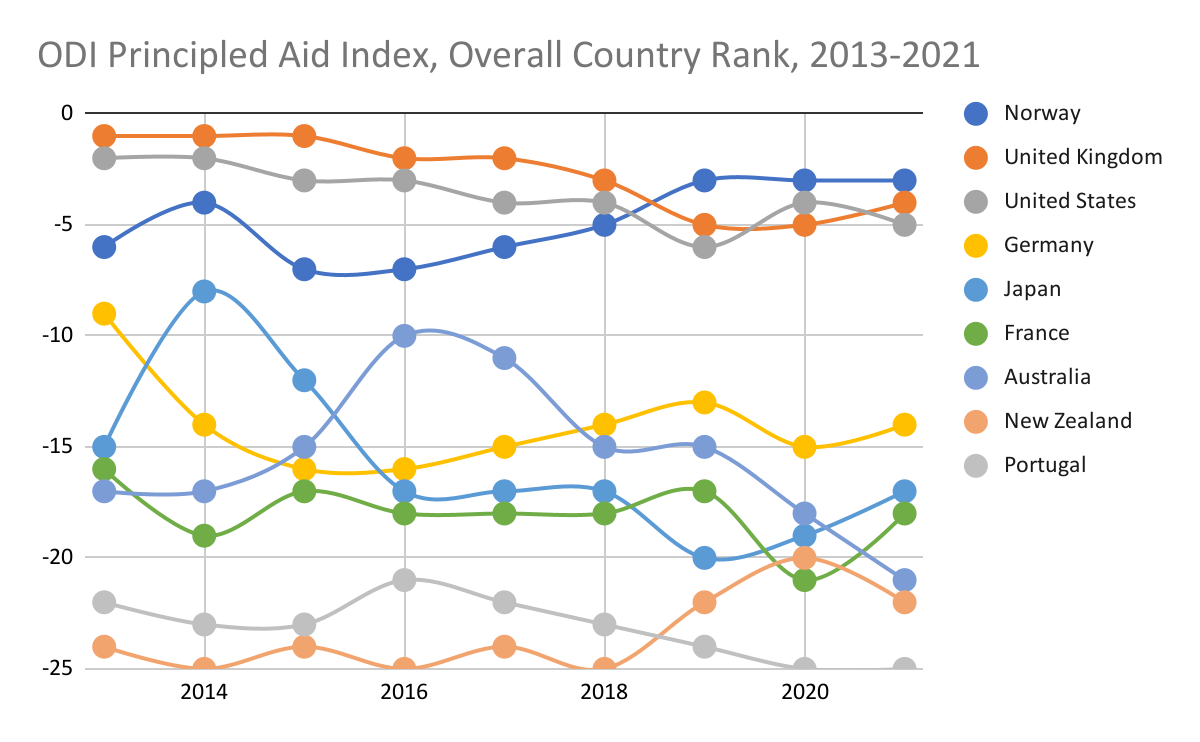

The latter task is aided by the Overseas Development Institute’s Principled Aid Index, which assessed Development Assistance Committee donors annually between 2013 and 2021 (Gulrajani & Silcock, 2023). It scored the U.S. and eight of our comparator countries on the extent to which their aid is aimed toward (i) reducing vulnerability and inequality (need-based), (ii) addressing shared global challenges (collective action), and (iii) avoiding aid to secure commercial or geostrategic advantage (public spiritedness). Figure 1 shows how these countries ranked against their peers on the index over nearly a decade, from 1 (high) to 29 (low).[2]

Figure 1.

Note: Figure includes the U.S. and eight comparator countries relevant to this study out of 29 Development Assistance Committee donors covered by the Principled Aid Index (2013-2021), including adjusted scores from the 2023 release (Gulrajani and Silcock, 2023). PRC and India are excluded from the analysis as they are not Development Assistance Committee member countries. Countries ranked closer to 1 (high) are considered to be more altruistic than their peers, while those closer to -29 (low) are considered to be more self-interested.

Rhetoric does not always add up to reality, which may explain why the UK and the U.S. remained top performers on the Principled Aid Index amid debate and uncertainty over their aid policies over the last decade (Gulrajani & Silcock, 2023). Nevertheless, declining ranks over time hint at domestic pressures these donors likely faced from populism, mercantilism, and isolationism.

U.S. presidents have long made it clear to Congress and the American public in national security strategies and policy statements that America has multiple interests (economic, security, diplomatic, humanitarian) for its development assistance. However, the last decade has seen U.S. rhetoric sharpen about Russia and the PRC. In development cooperation, this has manifested in using aid to help countries “build resilience” in the face of “malign influence” and “counter authoritarianism” (USAID, 2022, 2023a and 2023b; DoS, 2023).

This trend underscores a humanitarian motive to prevent the erosion of democratic norms in societies. There is also a clear geostrategic incentive to deflect potential threats to U.S. interests and influence from fierce competitors. Like Europe, U.S. political leaders have sought to rationalize development assistance in easing pressures from migrants and refugees fleeing economic and political instability in Central America and elsewhere. Curbing terrorism, infectious diseases, and drug trafficking have also been important security considerations.

In the UK, former Prime Minister David Cameron opened the door to a more explicit linkage between development cooperation and the national interest. His 2015 aid strategy was initially defensive, explaining the need to be responsive to the people’s demand that “aid spending…is squarely in the UK’s national interest” (DFID, 2015). Similar to France and Germany, UK aid strategies from 2015 through 2023 expressed security concerns about migration, terrorism, and refugee pressures, committing to focus resources and efforts to address root causes of instability (DFID, 2015; UKgov, 2021, 2022, and 2023). It redirected a substantial share of resources to pay for refugee costs at home at the expense of development programs abroad. Another significant driver of the UK’s aid policy in recent years has been economic: to broker new trade partners and advance economic interests, particularly following Brexit.

On the surface, Portugal and Norway appear to represent two extremes in their positioning on the Principled Aid Index: the former is seen as more self-interested, consistently falling towards the bottom, and the latter is seen as more “altruistic” rising to the top (Gulrajani & Silcock, 2023). However, these caricatures do not always fit the nuances of how each country pursues its foreign policy in the national interest. The Portuguese government argues that: “cooperation should be understood as an investment, rather than an expenditure, as development rather than aid, which complements and strengthens other aspects of foreign policy, including economic diplomacy and external cultural actions, with mutual benefits” (GoP, n.d.).

Portugal’s 2014-2020 Strategic Concept for Development Cooperation reinforces this ethos (GoP, 2014; OECD, 2023). Its new Portuguese Cooperation Strategy 2030 echoes this refrain, as senior officials pointed to the whole-of-society response to Mozambique’s cyclones as emblematic of the power of Portugal's private sector companies, development NGOs, and the state working together to cultivate mutually beneficial relationships and markets for the future (GoP, 2022).

Norway has traditionally enjoyed public and bipartisan political support for its assistance efforts (Lindkvist and Dixon, 2014; OECD, 2019). The last six government administrations from 2005 to the present day each stated a clear commitment to development cooperation within their broader foreign policy platforms (Tjonneland, 2022). Norwegian politicians followed this rhetoric with action, maintaining aid levels at roughly 1 percent of Norway’s gross national income between 2013 and 2022 (DonorTracker, 2023).

However, Norway also has a geostrategic objective to portray itself as a “humanitarian power” and exert outsized influence with a generous aid budget as part of its brand (Lindkvist & Dixon, 2014). Norway’s commercial, security, and humanitarian national interests shape the implementation of its aid policies, such as its reliance on income from oil and gas exports, its desire to protect the Norwegian agricultural sector, and navigating internal budget pressures to reallocate funds to cover rising in-country refugee costs s (Tjonneland, 2022; DonorTracker, 2023).

Australia and Germany were among the performers with greater variation on the Principled Aid Index over the time period analyzed (Gulrajani & Silcock, 2023). In Australia, this volatility may reflect a changing landscape for development assistance at home and abroad. Domestically, the last decade saw the loss of the country’s bipartisan consensus over the importance of aid with the 2013 election, which triggered budget cuts and structural changes to Australia’s aid program (Hill, 2023) before the new government pledged to rebuild the aid program in 2022 (Rajah, 2023).

Another game changer over the last decade has been the PRC’s growing influence in the Pacific region, which Australian leaders view as a geopolitical challenge requiring Australia to exert strength and renew ties with its neighbors (Tyler, 2023). Australia’s new 2023 cooperation strategy is likely a reaction to these underlying political tensions. It argues that bankrolling overseas development is in Australia’s national interest to promote stability, predictability, and prosperity because 22 of its 26 neighbors are developing countries (Tyler, 2023). Like Japan, the new strategy is more explicit about the linkages with Australia’s security and economic interests. Still, the government uses language reminiscent of Portugal’s or the PRC’s emphasis on mutual benefit(GoA, 2023).

Germany, like Australia, has grappled with how its foreign policy should respond to resurgent geostrategic competition with the PRC and Russia’s aggression in Ukraine (Öhm, 2021; Brechenmacher, 2023). The government issued guidelines in 2020 for its engagement in the Indo-Pacific and Africa, seeking to present a clearer value proposition for what Germany could offer (i.e., economic transformation in Africa, support for a rules-based order in Asia) and how it would work with others (Öhm, 2021).

Both policies reflect a geostrategic emphasis on strengthening Germany’s place as a middle power and a significant development cooperation supplier (Öhm, 2021; GoG, 2022). Other trends, from migration and refugees to public-private partnerships and feminist foreign policy, have also shaped Germany’s development cooperation strategy over the last decade (Öhm, 2021; Brechenmacher, 2023)).

While Germany defines its external engagement in economic terms, France positions itself as a global leader in combating fragility (de Galbert, 2015; OECD, 2018 and 2023). Initially, the emphasis was responding to an “increasingly unstable security environment” due to terrorism, failed states, and Russia’s expansionist aspirations (de Galbert, 2015). The 2017 election brought a renewed emphasis on development cooperation to combat root causes of insecurity (OECD, 2018 and 2023), though skeptics argue that France’s role as Africa’s “policeman” is motivated to protect French business interests, not Africans (Kommegne, 2022; Gain, 2023).

France has also sought to make a mark for itself in climate and gender—which cut across its diplomacy and development strategies (OECD, 2018 and 2023; Pallapothu, 2020). It shares Germany’s concerns regarding the need to contain and deter Russian aggression: it sent aid to Ukraine, vocally supported sanctions, and blamed Moscow for losing influence in the Sahel (Droin et al., 2023; Stronski, 2023).

Japan has long viewed its development assistance program as advancing export promotion and access to resources.[3] In the last decade, these linkages have become more explicit and geostrategic in official policy statements (Hoshiro, forthcoming). In 2015, the government argued that its aid program was essential to “maintain peace and security, achieve further prosperity, and realize an international environment that provides stability” (Japan MOFA, 2015). By 2023, this rhetoric intensified with Japan’s new cooperation charter (Kaizuka, 2023) in maritime security and the rule of law (Ursu, 2023).

Competition with an increasingly assertive PRC abroad, combined with economic slowdowns at home, changed the political calculus in favor of tying aid to advancing Japan’s economic and security interests (Hoshiro, forthcoming; Kaizuka, 2023). A quality infrastructure focus was not only intended to counterbalance the PRC but also support domestic firms struggling to maintain their competitiveness abroad (Hoshiro, forthcoming). Japan’s performance on the Principled Aid Index reflects these dynamics: consistently middle-of-the-road overall, but with a marked downturn between the early years of the PRC’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) versus the later years (2018-21) consistent with this atmosphere of heightened geopolitical competition (Gulrajani & Silcock, 2023).

New Zealand’s performance on the Principled Aid Index was consistently poor until a marked uptick beginning in 2019. In February 2018, New Zealand announced a ‘reset’ of its relationship with Pacific nations, characterized by increased engagement with and aid contributions to the region (NZ Parliament, 2019). According to the Lowy Institute’s Pacific Aid Map[4], Australia and New Zealand provided over a quarter (26 percent) of all aid to the Pacific Islands in 2020 (Dayant and Pryke, 2022). A consistent criticism of New Zealand’s aid program has been its narrow geopolitical focus; on the other hand, New Zealand's climate financing efforts and COVID-19-related aid have attracted high praise (Wood, 2023). Much like Australia, New Zealand grapples with geostrategic competition with the PRC in East Asia and the Pacific neighborhood.

2.2 Outside of the Club: From Recipients to Suppliers of Development Assistance

Emerging economies like the PRC and India may not be part of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee, but they are making their mark on the international finance landscape. Both have long-standing bilateral aid programs, dating back to the origins of the Non-Aligned Movement with the meeting of the 1947 Asian Relations Conference in New Delhi and the Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung, Indonesia. The PRC and India were leaders in the fight to “organize a common front of developing nations in their struggle against the domination of the rich Western world led by Europe and the U.S.” (Pedersen, 2021).

Overseas aid programs would become an essential part of this push towards “collective self-reliance” and solidarity in the pursuit of shared interests of economic advancement and political independence (ibid). However, neither the PRC nor India would operate assistance programs at the scale approaching, or in the case of Beijing surpassing, that of the Development Assistance Committee donors until the 2010s.

The PRC has a strong economic rationale for its modern development assistance program. It seeks raw materials and energy supplies to fuel its domestic industry, along with new export markets for Chinese products, labor, and technology (Hillman and Sacks, 2021; Custer et al., 2021).[5] The design and delivery of the Belt and Road Initiative is an extension of this logic, emphasizing large infrastructure projects that draw upon the overcapacity of PRC state-owned enterprises in the construction, steel, and cement industries at home (Horigoshi et al., 2022).

Aid has been a powerful sweetener for the PRC to convince foreign leaders to accept its territorial claims (e.g., Taiwan, Tibet South China Sea), cement its stature as an economic and military superpower, and inoculate itself against external pressure that threatens the Chinese Communist Party’s grip on power (Custer, 2022; Hillman and Sacks, 2021). These quid pro quo expectations are sometimes explicit: making access to assistance contingent upon accepting the One China policy and investing in the home districts of political leaders (Dreher et al., 2019; Custer et al., 2018 and 2019). In other cases, these expectations are more diffuse: inviting countries to work together for “win-win” outcomes via the BRI and its 2021 launch of the Global Development Initiative.

Like the PRC, India uses its aid program to help Indian companies gain access to new markets and strategic sectors as they find themselves competing with Chinese state-owned enterprises.[6] This competition also takes on a security dimension as India is concerned with ensuring a steady supply of energy to keep up with the demands of its hungry, growing economy at home (Mathur, 2021). Geostrategic competition with the PRC, which has intensified in recent years but dates back to the 1960s (Kragelund, 2010), is top of mind for India to maintain a precarious balance of power in South Asia (Mathur, 2021).[7]

In this battle for hearts and minds, the Indian government recognizes that there is an offensive and defensive dimension to aid, demonstrating India’s value as a preferred partner but also deterring neighbors from growing interdependence with the PRC (ibid). The emphasis on solidarity with the Global South that inspired its early cooperation efforts in the early days of the Non-Aligned Movement is apparent in India’s aid today (Pedersen, 2021; Mathur, 2021).

India’s development assistance relies heavily on technical cooperation to collaborate with counterpart nations on “agricultural development, human rights, urbanization, health and climate change” (Mathur, 2021). It views these activities as essential to brokering “functional partnerships” and “resilient supply chains” to minimize potential disruption to India’s economy and avoid overdependence on the PRC or Russia (Singh, 2022).

3. Architecture: How America’s Comparators Operationalize Their Assistance

How countries organize their aid infrastructure—from the agencies involved in foreign aid to the coherence of their foreign and domestic policies—influences the effectiveness of their aid programs and the degree to which they work in the national interest. Aid programs, organized well, can strengthen and be reinforced by efforts on other fronts such as trade, education, and public health. If aligned poorly, aid can counteract the work done by other parts of the government (OECD, 2021). In this section, we compare the number of players involved in donors’ aid programs and how they integrate and coordinate their efforts.

3.1 Number of Players: Fragmentation Versus Consolidation

Comparatively, the United States has one of the most crowded and fragmented playing fields among large aid providers—an estimated 20 agencies finance and implement development projects. As described in Chapter 1, this includes globally focused entities like the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, and the Department of State, along with geographically bounded agencies like the U.S. African Development Foundation and the Inter-American Foundation.

A considerable number of domestically-focused agencies maintain smaller technical assistance portfolios in their areas of respective expertise. Other agencies implement programs in specialized areas, such as the Department of Health and Human Services (in public health) or the U.S. Department of Agriculture (in food aid), or supply financing to crowd in private sector investments, such as the U.S. Development Finance Corporation.

The PRC’s aid architecture is even more complex than that of the U.S.. Beijing is not a new supplier of overseas financing for development—examples of its assistance date back to the 1950s (Horigoshi et al., 2022), managed primarily by the Ministry of Commerce (Malik et al., 2021). Nevertheless, in the last quarter century, as the scale and reach of Beijing’s overseas development assistance has grown astronomically, so too has the number of players involved in its financing and execution.

Over 300 public sector actors have financed or implemented Chinese-financed overseas development projects since 2000 (Malik et al., 2021).[8] This estimate includes between 20-30 government agencies at national, provincial, and municipal levels (Rudyak, 2019; Zhang et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2022), along with a much larger ecosystem of state-owned enterprises, state-owned policy banks, and state-owned commercial banks.[9]

The 2018 formation of the China International Development Cooperation Agency was an attempt by PRC leaders to tackle challenges of coordination, coherence, and effectiveness across its fragmented assistance architecture (Rudyak, 2019).[10] The new “vice ministry-level agency” sought to overcome interagency dysfunction stemming from intense competition over resources and political clout between the Ministry of Commerce’s commercially-oriented expectations for aid and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ argument that diplomatic and geostrategic goals should take preeminence (ibid).

On paper, the change in the aid architecture redrew organizational boundaries. The China International Development Cooperation Agency assumed aid-focused responsibilities and personnel from the other two agencies. Although it lacks the stature of a full ministry, the agency has a direct reporting line to the Chinese State Council and maintains its own “independent administrative structure” (Lynch et al., 2020). The China International Development Cooperation Agency was mandated to represent the government in negotiating country agreements, designing country strategies, and overseeing the delivery and evaluation of development assistance projects (Rudyak, 2019).

That being said, the China International Development Cooperation Agency is a paper tiger. Its mandate is limited to planning and coordination rather than execution or implementation of projects on the ground, which is primarily within the remit of the Ministry of Commerce, other line ministries, and Chinese state-owned enterprises (Lynch et al., 2020; Rudyak, 2019). While the China International Development Cooperation Agency has an upstream role in identifying country strategies and approving projects as well as evaluating results downstream, it has a limited say in what happens in between (e.g., funding and delivery). The agency’s influence is further constrained by the small size of its budget relative to other players (Sun, 2019)[11] and the continuous need to clarify the division of labor between itself, the Ministry of Commerce, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Yuan et al.,2022).

Most restrictive: the China International Development Cooperation Agency’s remit does not oversee the PRC’s extensive portfolio of projects financed with loans at varying rates of concessionality: financing at below market interest rates (Lynch et al., 2020). Given the prominence of debt-financed development within the PRC’s assistance program—which Malik et al. (2019) find accounts for the lion’s share of its assistance—this effectively consigns the agency to a marginal player at best within the PRC’s complex development assistance architecture.

If the PRC represents maximum fragmentation, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand are at the opposite end of the continuum. Their aid architectures have been centralized and increasingly so in recent years. For most of the last quarter century, the UK vested responsibility for its aid program under the auspices of an independent cabinet-level ministry: the Department for International Development. However, this status quo changed in 2020, when the UK government led by then Prime Minister Boris Johnson merged the department with the former Foreign and Commonwealth Office, bringing development and diplomatic responsibilities under one umbrella.

The Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office is also the sole shareholder of the UK’s dedicated development finance institution, British International Investment (formerly CDC Group), which operates as a public limited company with a single shareholder. Despite the heavy emphasis on using aid to open up new markets for the UK being evident in its broader national strategies (per Section 2), the government opted not to include commercial responsibilities within the new agency, instead situating these responsibilities within the Department of Business and Trade.

The UK government’s decision to consolidate its development and diplomacy functions under one umbrella was partly philosophical—signaled by the release of the 2015 aid strategy, which sought to more closely align aid with economic and geostrategic interests (Worley, 2020)—but also reflects an interagency competition over scarce resources. For years before the merger, the government faced public sector budget cuts. Aid was an exception, as the government was required to meet the OECD’s recommended target of 0.7 percent of gross national income (GNI) per the parliament’s International Development Assistance Act of 2015 (Loft and Brien, 2022).

This dynamic made the aid budget, and DfID in particular, an attractive target for politicians who sought to claw back the agency’s mandate and redirect budgets to other agencies (Krutikova and Warwick, 2017). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK government reduced aid spending to 0.5 percent as a “temporary measure,” and legislation passed in 2021 outlined two economic tests to be met before restoring spending at the 0.7 percent level (ibid).

Several years prior, Australia pursued a similar change to its aid architecture, folding the former development agency (AusAid) into the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in 2013. One critical divergence from the UK example was that Australia’s merger incorporated trade alongside development and diplomacy. Like the UK case, the Australian government’s decision to dissolve its aid agency and merge these functions within its foreign ministry occurred in an environment rife with public sector budget cuts, where the aid agency (AusAid) was seen as maintaining a relatively large and protected budget[12] (Pryke, 2019).

The merger also reflected a philosophical stance promoted by the conservative government led by Prime Minister Tony Abbott of the need for a “new paradigm” that reflected Australia’s national interests and a “changed context” where private funding (e.g., Foreign Direct Investment, remittances, trade) would play an outsized role relative to traditional aid (DFAT, 2014; Hill, 2023). The integration of the development, diplomacy, and trade portfolios may have inspired better policies on labor mobility, helped rebuild a beleaguered diplomatic corps, and provided a useful refresh to how Australia engaged with the Pacific (Pryke, 2019). But there were substantial challenges.

Like Australia, New Zealand’s aid agency called the New Zealand Aid Programme, is situated within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, which spells out the concerted trade, foreign affairs, and development efforts the ministry must undertake. On the ministry’s website, there is a clear statement of national interest as they affirm “[t]he Ministry acts in the world to build a safer, more prosperous and more sustainable future for New Zealanders” (MFAT, n.d.a.). The Ministry pursues sustainable solutions, prosperity, security, and influence in the service of the citizens of New Zealand (ibid). In November 2019, New Zealand’s cabinet adopted its policy on International Cooperation for Effective Sustainable Development, which reiterated a focus on engaging in the Pacific region (MFAT, n.d.b.).

There are two theoretical upsides to the consolidation pursued by the UK, New Zealand, and Australia: (i) the potential to synchronize instruments of national power to work together in advancing national interests rather than in isolation and (ii) overcome interagency coordination and coherence challenges through co-locating diplomacy and development (and trade in the case of New Zealand and Australia) under one umbrella. However, observers familiar with these restructuring efforts argue that the costs outweigh the benefits.

They point to three unintended consequences of the mergers that have negatively impacted the ability of New Zealand, Australia, and the UK to deliver development assistance in ways that advance their multiple national interests. Diplomats, already overstretched, now have the additional burden of running aid programs, scattering their attention in many more directions. The merger and move to curb the independence of aid programs triggered a loss of valuable technical expertise in the design and delivery of effective development, as specialized personnel left the newly combined agencies in protest or frustration. Without an independent development agency, the humanitarian or moral imperative for aid became subsumed or demoted to second-tier status to other competing interests. This manifested in relatively higher cuts to development versus diplomatic funding and staffing.[13]

India also lacks a dedicated development cooperation agency. However, this is less by design than it reflects the insufficient political will to overcome competing interagency interests that have stymied past attempts to reform the aid architecture. Instead, India’s bilateral aid program is managed by a department under the Ministry of External Affairs, the Development Partnership Administration, with involvement from several other agencies (Mathur, 2021), making it somewhat similar to the U.S. and the PRC in terms of the wide bench of players involved. The Development Partnership Administration is responsible for technical cooperation, humanitarian assistance, grant-based assistance, and project appraisals for lines of credit and concessional loans issued by the Ministry of Finance and Export-Import Bank of India (OECD, 2023). The Ministry of Finance retains separate responsibility for multilateral assistance.

However, the Development Partnership Administration’s ability to incentivize and compel coordination across interagency players is highly constrained by its relative lack of status (Mathur, 2021). Although this affects long-term development and short-term crises alike, the uncertainties and inefficiencies of multiple actors working relatively autonomously absent a robust coordination mechanism are most evident in humanitarian assistance.[14] As Shanbog and Kevlihan (n.d.) note, humanitarian assistance has become a growing area of focus for India. It is plagued by organization and coordination challenges from unclear chains of command and opaque decision-making processes.

3.2 Positioning of Development Assistance: Degree of Integration and Coordination

The remaining aid providers fall between the two extremes of complete consolidation versus complete fragmentation. Most donors in this group have a defined development cooperation entity, which often falls under the oversight of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and a development finance institution (i.e., a specialized bank or subsidiary entity to support private sector development in low- and middle-income countries). Some countries have additional specialized agencies, though donors in this group do not typically have the breadth of players evident in the U.S. and PRC. There is more variation in the degree to which development cooperation entities are integrated within broader foreign policy structures and conversations, as well as approaches to coordination.

In Norway, most aid players are integrated under the oversight of a Minister of International Development[15] under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, a directorate, is responsible for roughly half of Norway’s aid portfolio (OECD, 2023). It not only manages and implements its own grant-funded programs but also those overseen by the separate Ministry for Climate and Environment, which is responsible for Norway’s International Climates and Forests Initiative (ibid). In addition, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation holds responsibility for development assistance reporting and quality assurance.

The Norwegian Investment Fund for Developing Countries, a development finance institution, is owned and funded by the government with a mandate to facilitate sustainable business investment in developing countries through loans and risk capital (Norfund, n.d.). It has its own board of directors, appointed by the General Assembly, though the Minister of International Development represents the government’s oversight of the fund (ibid). The Norwegian Agency for Exchange Cooperation primarily focuses on knowledge exchange activities.

In contrast to the U.S., which charges the Treasury for engaging with multilateral development partners, Norway keeps this under the Minister of International Development (OECD, 2019). Similar to America, overlapping mandates between the Minister of International Development and the rest of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs created coordination challenges and duplication that have been the focus of many reforms (ibid). For example, the Minister of Foreign Affairs separately oversees budgets for peace and reconciliation, as well as conflict stabilization and fragile states, outside of the authority of the Minister for International Development (ibid). The Minister of Foreign Affairs also has the mandate for thematic areas related to humanitarian assistance, human rights, and the oceans, as well as some geographic regions (e.g., the Middle East, North Africa, Afghanistan) (ibid).

Two areas highlighted as opportunities in Norway to foster greater coherence and cooperation across these actors (and others) may be relevant in the U.S. context. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is important in developing unified multi-year country strategies that integrate aid and non-aid tools in a whole-of-government approach to advance development cooperation. Secondly, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has used broader development frameworks like the UN sustainable development goals to spur interagency dialogue and identify areas of complementarity for shared action (ibid).

Japan also has a relatively integrated set of aid players and is among the most hierarchical in its decision-making of the donors examined in this study. The Japan International Cooperation Agency is responsible for implementing programs related to bilateral grants, loans, and technical assistance for its partner countries (OECD, 2023). It plays a role in delivering emergency relief; both donated supplies and emergency response teams (ibid). However, as an incorporated administrative agency, the Japan International Cooperation Agency is strictly an implementer of development programs directed and contracted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which determines cooperation policies (OECD, 2021). Similar to Norway, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is responsible for contributions to multilateral organizations.

The Prime Minister’s office is a force for integration, particularly in infrastructure financing. It convenes a Management Council for Infrastructure Strategy with a broader set of actors: Japan’s Bank of International Cooperation; the Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry; Japan Oil, Gas, and Metals National Corporation; the Nippon Export and Investment Insurance; the Japan International Cooperation Agency; and the Japan External Trade Organization (OECD, 2021). The high-level involvement of the PM’s office reflects the fact that the Council explicitly seeks to advance multiple national interests with its infrastructure investments: economic (promoting Japanese exports), geostrategic (building goodwill and allies), and humanitarian (strengthening the capacity of partner countries) (ibid).

Nevertheless, the Achilles Heel of the high political visibility for development assistance in Japan is that decisions on what to fund, where, and how are primarily constrained by the need for central government or even cabinet-level approval in some cases.[16] This has the unintended consequences of decreasing Japan’s responsiveness to what partner governments want and its in-country representatives recommend and making the decision-making process for new projects longer and less efficient (ibid).

Development cooperation is accorded substantially greater autonomy in Germany than in the case of Japan or Norway. Germany has a specialized cabinet-level agency with its minister for this purpose, the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, rather than being subordinate to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (OECD, 2023). As with Norway, there is a demarcation between long-term development assistance (the domain of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development) versus humanitarian assistance and conflict and stabilization for countries in crisis (the domain of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) (OECD, 2021). It is unclear whether this helps or hinders coherence between these functions, as discussed in Chapter 3.

Germany has two implementing entities and subsidiaries—both of which are accountable to the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. The German Agency for International Cooperation and Kreditanstalt fur Wiederaufbau (KfW) is focused on partner country governments—supplying technical assistance and financial cooperation, respectively (OECD, 2023). The German Investment Corporation, Germany’s development finance institution, is positioned under KfW, along with the KfW Development Bank (ibid). The German Institute for Development Evaluation is a specialized entity that operates as a research institute to improve the effectiveness of its assistance.

Germany is one of the few remaining donors that accords development cooperation and the political prominence of a dedicated cabinet-level ministry. This architectural choice has its benefits. It elevates development as an essential instrument of national power alongside defense and diplomacy. It ensures this perspective informs cabinet-level deliberations on foreign policy without intermediation by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Moreover, it provides political space for the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development and its implementers to develop a deep specialization in development, attract and retain professional staff with relevant technical expertise, and focus on the design, delivery, and evaluation of sound aid projects, somewhat shielded from other imperatives.

But this status quo also has trade-offs. Although not as diffuse as the U.S. and the PRC cases, Germany has a sufficiently large number of players operating in relative independence to make coordination and coherence more difficult than donors with streamlined systems. Having a separate ministry for development cooperation apart from foreign affairs or trade, combined with a culture that privileges autonomy and egalitarian decision-making, can make it challenging to exploit synergies across instruments of national power for a more holistic way of engaging partner countries in combining both aid and non-aid tools (OECD, 2021).

Even among the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development and its implementing entities, a high degree of decentralization can lead to a proliferation of strategies, policies, and procedures, which may be duplicative, confusing, or working at cross-purposes (ibid). The many central-level players, combined with a relatively weaker presence within embassies (under the remit of the separate Ministry of Foreign Affairs), may also have the unintended consequence of making German development cooperation less nimble and effective in responding to the demand and needs of their partner country counterparts (ibid).

France, too, has a lead development cooperation agency, the French Development Agency, which is responsible for financing to support governments and non-governmental organizations. But this belies a much more complex aid architecture comprising 14 ministries, managing 24 separate budget programs (OECD, 2018). The French Development Agency is part of an umbrella group, along with France’s development finance institution, the private-sector-focused Proparco, and Expertise France (a technical cooperation entity) as subsidiaries (OECD, 2023).

The French Development Agency Group is jointly overseen by two ministries: the Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs and the Minister of the Economy, Finance, and Recovery. The government also proactively engages non-governmental stakeholders (e.g., NGOs, universities, trade unions) around the nation's development policy through a 67-member National Council for Development and International Solidarity, which meets three times annually along with supporting working groups (GoF, n.d.).[17]

Compared to Germany or Norway, the fact that no one minister is responsible for development cooperation could inadvertently dilute this perspective within broader foreign policy decisions (Faure, 2021). It also adds complexity to the coordination among many players, and observers familiar with these institutions noted persistent power struggles between the Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs and the French Development Agency. Against this backdrop, France passed a Law on Inclusive Development and Combating Global Inequalities in 2021, in line with President Emmanuel Macron’s emphasis on modernizing French foreign aid. The law lays out more focused policy objectives and recommended financing levels but also changes how aid should be governed and evaluated (Faure, 2021).

An independent evaluation commission was formed to report to parliament on the impact of French aid on the ground (Faure, 2021). A Development Council chaired by the French President builds interagency consensus on strategic-level decisions related to development cooperation as a tool within France’s broader engagement with other countries (ibid). Led by the Prime Minister, an Inter-ministerial Committee for International Cooperation and Development takes additional decisions to set the parameters for how France’s development cooperation policy should be implemented (e.g., priority country selection, bilateral and multilateral aid allocations) (ibid).

The law also significantly clarified leadership for French aid efforts on the ground, identifying the ambassador in each country as the focal point for coordination among various development cooperation actors (ibid). Implementation of the new legislation is still nascent to judge whether it has improved the coordination and coherence of French aid in practice. Still, some of its features may be worth considering in the U.S. context.

Portugal has a similarly complex set of government ministries involved in aid as France, operating in a more decentralized system. Instituto Camões I.P. (the lead agency for Portuguese development cooperation, language, and culture promotion) is responsible for “steering and coordinating” the country’s assistance efforts. Its sister agencies generally accept this role (OECD, 2022).[18] Perhaps reflective of this multi-stakeholder environment, engagement with multilateral institutions is not the remit of a single agency but a shared responsibility of Camões I.P., the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Finance (ibid). Portugal has a private-sector-focused development finance institution: Sociedade para o Financiamento do Desenvolvimento.

Although formal coordination processes exist, such as the requirement for ministries to secure Camões I.P. approval for their development cooperation activities (ibid), observers familiar with these institutions indicate that it is more common for coordination and information sharing to occur informally and bilaterally between the respective ministries rather than working across all the actors. Moreover, the emphasis of this coordination appears to be more at the operational level than necessarily focused on strategic-level coherence or medium- to long-term priorities, increasing the risk that its efforts fail to add up to more than the sum of their parts (ibid). Like France, however, the Portuguese government has established a vehicle to engage its public to give input to its aid policies via its annual Development Cooperation Forum (ibid).

One innovation that could be useful for the U.S. to watch and learn from is Portugal’s use of Portuguese Cooperation Centers at the country level. Overseen by relevant embassies, the Portuguese Cooperation Centers are “administratively independent entities” based in partner countries that can hire local staff and could, theoretically, become a clearinghouse for disparate ministries to channel and coordinate support in ways that are responsive to counterpart nation goals (OECD, 2022). However, this is more an aspiration than reality, as the Portuguese Cooperation Centers have relatively limited authorities to support the implementation of projects as opposed to direction setting, though Camões I.P. does intend to devolve additional decision-making mandates to the Portuguese Cooperation Centers in the future (ibid).

4. Focus: How America’s Comparators Prioritize Their Assistance

Donors are increasingly caught between addressing complex development challenges abroad that can have real impacts in their own countries and increasing pressure on their budgets to address intensifying uncertainties at home. To appreciate the complete picture of why donors behave the way they do, it is helpful to not only look at what donors say about their stated priorities via strategies, policies, and statements but also what they do by examining their revealed priorities via attributes of their assistance flows.

In this section, we look at how donors give assistance: how much they give, with what terms, in which geographies and sectors, and to what extent is this bilateral spending or channeled multilaterally? In answering these questions, we can pinpoint what donors prioritize in practice beyond their rhetoric. Table 2 provides a summary to compare similarities and differences in how our ten comparator countries vary in aid volume, terms, channels, and generosity.

Table 2. Comparing Aid Volumes, Terms, Channels, and Generosity—A 10-Year Average

|

Country |

Volume: Annual Aid (ODA) and Debt (OOF), in millions |

Generosity: Annual Aid and Debt Dollars Given Per Capita[19] |

Terms: Percentage of Annual Giving in Grants |

Channels: Ratio of Annual Bilateral: Multilateral Giving |

|

Australia |

3,398.45 |

130.82 |

91.1 |

69:31 |

|

China (PRC)* |

150,817.00 |

106.8 |

30.3 |

unknown |

|

France |

11,100.65 |

163.4 |

46.8 |

67:33 |

|

Germany |

29,995.28 |

356.75 |

53.6 |

77:23 |

|

India |

701.27 |

0.49 |

unknown |

unknown |

|

Japan |

25,312.70 |

202.3 |

22.8 |

83:17 |

|

New Zealand |

459.67 |

89.71 |

97.1 |

74:26 |

|

Norway |

4,024.01 |

737.39 |

89.9 |

62:38 |

|

Portugal |

381.64 |

36.77 |

41.5 |

60:40 |

|

United Kingdom |

13,498.81 |

201.56 |

90.2 |

55:45 |

|

United States |

41,056.16 |

123.19 |

79.9 |

76:24 |

Notes: For Australia, France, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States, the data was gathered from the OECD.Stat for years 2012-2021. *For the PRC, the data was gathered using AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Database for 2008-2017, Version 2.0. For India, the data was collected from the website of the Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. All financial figures use USD 2021. Donor per capita spending estimates use population statistics available from the World Bank.

4.1 The Bottom Line: Volume, Generosity, and Terms of Financing for Development

Donor countries vary greatly in their spending power, or at least what they are willing to devote to supporting development in other countries. The PRC leads the U.S. and comparator countries by a wide margin in the sheer volume of financing it mobilized for development between 2008 and 2017 (the last ten years of data available): US$150.8 billion per year/on average (constant 2021). The U.S., Germany, Japan, and the UK are among the largest Development Assistance Committee donors reporting to the OECD’s Creditor Reporting System, supplying an average of US$13.5 billion (UK) to US$41.1 billion (U.S.) in overall financial flows between 2012 and 2021. Whereas some donors bankroll development in the billions yearly, other bilateral suppliers do so in the millions. As shown in Table 2, Portugal, New Zealand, and India had comparatively smaller budgets, ranging between US$381.6 million (Portugal) and US$701.3 million (India).

Of course, overall volume is only one way to compare donors; another is generosity. In this vein, we estimate each donor’s spending power per capita (i.e., how much money is given for each person in the donor country). Norway, Germany, and Japan are the most generous on this measure, punching well above their small size in giving between US$202 (Japan) and US$737 (Norway) per person. India and the PRC are less generous, supplying between 50 cents (India) and US$107 per person. This is perhaps unsurprising for two middle-income countries with some of the largest populations in the world. Yet, this is not unique to emerging markets, for Portugal and New Zealand also each spent less than US$100 per person on development aid.

Many comparator countries still supply the majority of their assistance grants, though even for these donors, the share of funds they provide through loans is growing. New Zealand, Australia, and the UK gave 90 percent or more of their development assistance dollars on average through grants. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Japan gave roughly three-quarters of its assistance in loans, with the PRC not far behind with debt and equity accounting for two-thirds of its portfolio.[20] France, Germany, and Portugal appear to have the most balanced portfolios, with approximately 42 to 54 percent of their assistance in the form of grants versus loans.[21]

However, it is important to underscore that not all loans are equally burdensome for recipient countries: the devil is definitely in the details of the specific lending terms (i.e., interest rates, repayment periods, risk premia like collateral requirements). For example, the average loan from a Development Assistance Committee donor like Germany or Japan would typically come with a 1.1 percent interest rate, a repayment period of 28 years, and seldom requires collateral requirements or other risk premia. Comparatively, the PRC’s lending is much more similar to a commercial bank. The average loan from the PRC has a 4.2 percent interest rate and a repayment period of less than ten years (Malik et al., 2021). Sixty percent of projects require one or more of the following as a hedge against default: collateral (usually liquid assets), repayment guarantees, or credit insurance (ibid).

Between 2012 and 2021, the U.S. development assistance was heavily oriented towards grants (80 percent) rather than loans (20 percent). Even among assistance given in the form of loans, terms were more similar to the high degree of concessionality (no- or low-interest, longer repayment and grace periods) of the other Development Assistance Committee donors. This profile has been consistent in the decades following the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative launched by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in the 1990s, following a rising tide of debt distress in low- and middle-income countries struggling to service their loans from advanced economies.

However, some early signals indicate the U.S. portfolio may be changing, at least in terms of its openness to supporting developing countries with a wider array of financial instruments, including loans, loan guarantees, and blended finance instruments. As discussed in Chapter 2, with the formation of the Development Finance Corporation in 2019, Congressional and executive branch leaders gave the agency a larger spending cap than its predecessors to provide less concessional financing and risk insurance to crowd in more private sector dollars to support overseas development. After a relatively slow start, U.S. Development Finance Corporation investments contributed to a US$20.3 billion increase in USG debt financing (i.e., other official flows) in 2021 compared to the year before. U.S. debt-financed assistance expanded from 4 to 36 percent of its portfolio between 2020 and 2021, substantially altering the ratio of aid to debt.

4.2 Channel of Choice: Giving Bilaterally or via Multilateral Channels

Donor countries also vary in how much they prefer to pool their resources with others in channeling assistance via multilateral development banks, UN agencies, or sector-focused vertical funds versus bilateral aid programs that give directly to counterpart nations. Between 2012 and 2021, five donors were the most multilaterally-minded (e.g., the UK, Portugal, Norway, France, Australia), directing roughly one-third or more of their aid through multilateral channels. This could reflect a recognition among some middle-tier donors (in absolute dollars) that assisting multilateral mechanisms could boost the impact and influence of each dollar spent by pooling resources with other countries that share their interests.[22]

Comparatively, Japan, Germany, the U.S., and New Zealand used multilateral channels least often among the donors we compared. Larger donors, like the U.S., Germany, and Japan, have ample convening power and resources on their own may consider channeling their assistance via multilateral institutions as a dilution of their influence. In the context of the U.S., there is an additional dynamic of historical skepticism and distrust of international organizations like the United Nations among many political leaders and the American public writ large.

The PRC and India are difficult to directly compare along the same lines, as data on their multilateral spending is scattered and sparse. There is some evidence to indicate that the PRC and India have become more prominent multilateral donors in the last decade. A comparative study of 13 emerging economies highlighted that the PRC increased its annual contributions to multilateral development banks by “twenty-fold from $0.1 billion to $2.2 billion” between 2010 and 2019 (Mitchell and Hughes, 2023). Taken together, the five BRICS countries (including the PRC and India) contributed $23.5 billion in core financing to multilateral organizations over that same decade (ibid). Yet, for an actor like the PRC, this remains quite small compared with the size of its overall aid program, indicating that most of its assistance is still channeled bilaterally.

The rise of alternative multilateral venues, such as the Asian Infrastructure Bank in 2016 and the New Development Bank in 2015, has sparked controversy in recent years. Led by emerging rather than advanced economies, this new breed of multilaterals appears to have shifted giving patterns. Before the two alternative banks were created, emerging donors like the PRC and India channeled most (41 percent) of their multilateral giving to UN agencies. By contrast, this share fell to 17 percent, more in line with the Development Assistance Committee donor average (16 percent), once the two new organizations were created (ibid).

4.3 Where does the money go?: Geographic Focus

Many donors have a proclivity to work with countries in their backyard—after controlling for income, disasters, and civil war (Bermeo, 2018).[23] There is an implicit logic to this. Donors are likely to have greater familiarity, history, and relationships with their regional neighbors. Political leaders in donor countries may enjoy stronger public support to engage with countries closer to home, as the perceived threats of poverty and instability spilling across borders are higher. Other donors view their ‘neighborhood’ as not strictly defined by geographic region but based upon shared history, language, and culture. Although they often are not exclusively focused on these countries, they orient a disproportionate share of resources there to amplify their impact.

New Zealand focuses nearly 60 percent of its aid in the Pacific (MFAT, n.d.b.). India prioritizes South Asia, with top recipients located fairly close to home: Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Mauritius, Maldives, Myanmar, and Seychelles (MEA, n.d.a.). Japan’s historical interest has been a bit broader in encompassing all of Asia, and its top recipients come from all corners of the region: South (India, Bangladesh), Southeast (Myanmar, Vietnam, Indonesia, Philippines, Cambodia), and Central (Uzbekistan). Australia, similarly, casts its geographic focus as the Indo-Pacific (Purcell, 2023). Portugal’s comparative advantage and interest have been working with Portuguese-speaking countries in Africa, as well as Timor-Leste. Similarly, France has historically worked with Francophone West Africa, particularly the Sahel region.

Other donors choose to engage farther afield, operating in a large number of geographic regions simultaneously. In a hyperconnected world, donors recognize that many of the earth’s most intractable problems—ideological extremism, irregular migration, communicable disease, physical instability, climate change—rarely respect national boundaries. For some donors, this global reach reflects a sense of their national identity and position in the world, buoyed by somewhat larger development resources in money and staffing to realize this vision in practice.

Norway’s assistance footprint aligns with its reputation of engaging in the places of greatest need, with a strong commonality of conflict-affected states across top recipients.[24] The U.S. and the UK are global players with a growing emphasis on Sub-Saharan Africa in the last decade. The PRC has broadened its geographic footprint considerably in recent years, deploying the preponderance of its assistance to sectors related to infrastructure on a global scale.

5. Performance: How Partner Countries Assess Their Development Partners

Aid in the national interest is not solely about donor countries as the suppliers of development assistance dollars. It must also consider the demand side: what do counterparts in low- and middle-income countries expect of the assistance providers with whom they choose to work? Answering that question is equally important regardless of whether the interest in question is parochial (acquiring direct benefits now), geostrategic (securing leverage later), or completely enlightened (making the world a better place).

In all three cases, donor countries need willing partners to make or influence decisions favorable to advancing their interests, whether selfish or to the mutual benefit. To assess how well positioned the U.S. and our ten comparator donors are in the eyes of counterparts in the Global South, we draw upon the findings of the 2020 Listening to Leaders Survey of nearly 7,000 public, private, and civil society leaders conducted across 141 low- and middle-income countries (Custer et al., 2021). There are two dimensions from the survey of developing country leaders that are valuable indicators in this discussion of national interest.

On the one hand, if a bilateral donor is motivated by geostrategic self-interest, they may more heavily weigh how counterpart nations assess their influence in shaping domestic policy priorities. On the other hand, if a donor is motivated by enlightened self-interest, they may place a higher premium on how counterparts view their helpfulness in the design and delivery of critical development reforms. In reality, we believe that donors have multiple and mixed national interests that jockey for positions and that these interests can evolve, so they should be paying attention to both metrics.

Table 3. Leader Perceptions of Donor Influence and Helpfulness, 2020

|

Country |

Footprint: # of countries reported receiving advice or assistance from the donor |

Influence: % of respondents rating donor as influential (rank out of 69) |

Helpfulness: % of respondents rating donor as helpful (rank out of 68) |

|

United States |

132 countries |

83.4 (3rd) |

85.6 (7th) |

|

China (PRC) |

113 countries |

75.8 (8th) |

76.6 (32nd) |

|

UK |

120 countries |

75.5 (10th) |

82.9 (15th) |

|

Germany |

126 countries |

71.4 (15th) |

80.9 (21st) |

|

Portugal |

25 countries |

71.1 (16th) |

75.8 (36th) |

|

Japan |

131 countries |

68.4 (18th) |

80.7 (24th) |

|

New Zealand |

52 countries |

68.4 (19th) |

83.8 (11th) |

|

France |

114 countries |

64.5 (30th) |

72.5 (44th) |

|

Australia |

76 countries |

63.2 (34th) |

76.3 (35th) |

|

Norway |

101 countries |

63.1 (36th) |

81.5 (20th) |

|

India |

79 countries |

56.8 (51st) |

70.9 (50th) |

Notes: Source data from AidData’s Listening to Leaders 2020 survey (Custer et al., 2021). Countries are ordered in descending ranks on the “influence” indicator. Respondents could only assess the influence and helpfulness of donors from whom they reported receiving advice or assistance. Performance ratings were scored on a Likert scale of 1 (not influential/helpful) to 4 (very influential/helpful). Donors were then ranked from 1 (best) to 69 (worst) based on their scores on each measure relative to their peers. The original survey invited leaders to assess a field of up to 100+ bilateral and multilateral aid agencies; countries with multiple agencies were then collapsed to provide a single score.

5.2 Influence: Who do developing country leaders listen to most in setting policy priorities?

Regarding the biggest influencers, something is to be said for being a big spender. Traditionally, the largest bilateral development assistance providers, such as the U.S., the PRC, the UK, and Germany, tend to top the ranks of the most influential donors out of over 100. However, money is not entirely deterministic. Some smaller players command outsized influence relative to the size of their portfolios; this was true for Portugal. Conversely, some big spenders punched below their expected weight on influence: France and Australia. One of the greatest predictors of performance overall was that donors were viewed as more influential (and helpful) when they were seen as aligned with the priorities of counterpart nations: channeling advice and assistance to support the development problems Global South leaders most wanted to solve (Custer et al., 2021).

As discussed in Section 4, some donors choose to go deep in specializing in specific geographies and sectors. In this respect, an overall level of influence may matter less than the degree to which a donor can exert sway over the countries and sectors it deems most aligned with its interests. For example, India and Japan hold the greatest influence among leaders in their respective regions, South Asia and East Asia and the Pacific. Portugal is one of the top ten most influential donors in Sub-Saharan Africa, which has been its priority area of focus in building upon common language and history via colonial ties. Norway has carved out a clear niche as an influential environmental player. This area is strategically aligned with the priorities outlined by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Germany was highly influential in the governance sector, aligning with its strategic interest in curbing migration flows. This may reflect its efforts to fight root causes of displacement and instability that become powerful drivers or migrants.

5.3 Helpfulness: Who do developing country leaders turn to to help advance reforms?

The most influential donors were often seen to be the most helpful to their partner countries. The U.S. is the best example of this, as the sole bilateral donor to chart in the top 10 of both the influence and helpfulness performance measures.[25] New Zealand, the U.K., Norway, Germany, and Japan all fell within the top 25 most helpful donors out of 100+. The PRC was the clearest outlier to this trend: it was viewed as substantially less helpful than its donor peers despite its high perceived influence.

In another nod to the power of specialization, middle powers that doubled down on specific sectors and geographies tended to be seen as influential in those spaces and places and quite helpful. This state of play was true, for example, of Australia (rural development), Germany (governance), India (South Asia), and Japan (throughout the Indo-Pacific). However, this specialized focus could also be a question of the relative availability of resources. For larger donors like the U.S. it has traditionally had the money and the people power to maintain its support across a breadth of countries and sectors in ways that could be prohibitive for a smaller player.

6. Conclusion

Development assistance can be a difficult and divisive political issue. Donors maintain a tricky balancing act: ensure stability and prosperity at home, avert threats from abroad, improve the country’s standing both domestically and internationally, and be good global citizens. In this respect, it is likely unproductive to demonize or lionize aid, depending on whether it is “in the national interest” or not. Countries will act in their self-interest. It is more productive to ensure that they do so more often in ways that are positive-sum, not zero-sum.

In this paper, we provided an overview to understand how donor countries articulate their national interests and how they resource, allocate, and coordinate their aid architectures. We reflected on how well donors positioned themselves with counterpart leaders in the Global South to realize their interests, as well as considered insights and lessons for the U.S. as it seeks to strengthen its development assistance in the future.

Being frank and forthright that development assistance serves multiple national interests is not only the right thing to do, it is the smart thing to do. Strategically, it allows for a more honest and clear-eyed discussion within donor countries about what its development assistance should achieve and why. Operationally, this clarity facilitates coherence regarding how development assistance should intersect with foreign policy, national security, and economic growth. Relationally, it allows donors to level the playing field and work with counterparts from a place of true partnership centered around mutual benefit and shared goals.

7. References

Acharya, S. and Singh, S. C. (September 2023). G20 admits African Union as Permanent Member. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/g20-admit-african-union-permanent-member-new-delhi-summit-draft-declaration-2023-09-09/

AFD. (n.d.). The Agence Française de Développement Group. https://www.afd.fr/en/agence-francaise-de-developpement

Alesina, A. and D. Dollar (2000). Who gives foreign aid to whom and why? Journal of Economic Growth 5 (1), 33–63.

Asmus, G., Eichenauer, V., Fuchs, A., and Parks, B. (September 2021). Does India Use Development Finance to Compete with China? A Subnational Analysis. AidData Working Paper #110. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary. https://www.aiddata.org/publications/does-india-use-development-finance-to-compete-with-china-a-subnational-analysis

Brechenmacher, S. (2023). Germany has a new Feminist Foreign Policy: What does it mean in practice? Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. March 8, 2023. https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/03/08/germany-has-new-feminist-foreign-policy.-what-does-it-mean-in-practice-pub-89224

Bermeo, S. (2017). Aid Allocation and Targeted Development in an

Increasingly Connected World. International Organization, 71(4), 735-766.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-organization/article/aid-allocation-and-targeted-development-in-an-increasingly-connected-world/7478DF8E264AE5C876EDD96B86CB0E9D

Bermeo, S. (February 2018). Development, self-interest, and the countries left behind. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/development-self-interest-and-the-countries-left-behind/