Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus: Successes, Failures, and Lessons from U.S. Assistance in Crisis and Conflict

Gates Forum II Background Research

Ana Horigoshi, Samantha Custer[1]

AidData | Global Research Institute | William & Mary

November, 2023

Executive Summary

Crises and conflict have become the new normal, and U.S. assistance must strike a balance: provide short-term relief to communities in distress, build long-term resilience to help countries tackle root causes of poverty and instability. This paper examines how the U.S. and other donors integrate humanitarian response, peacebuilding, and development assistance. U.S. agencies must translate the aspirations of the Global Fragility Act into practice, steward an assistance portfolio increasingly focused on emergency response, and navigate fatigue from involvement in protracted crises with no end in sight. We surface three cross-cutting lessons for consideration.

A Long-Term Strategic Approach Grounded in Realism, Aimed at Resilience: America’s success metrics in delivering‰ assistance in crisis and conflict should shift from how quickly money is spent to how well it moves countries one step closer to resilience. U.S. agencies need holistic, long-term plans paired with flexible and nimble financing to help countries transition between crisis response and long-term development. While a high volume of large-scale projects with hefty price tags sounds impressive, overly ambitious projects have proven hard to implement and diminished U.S. credibility in the eyes of counterparts in Haiti and Iraq. Instead, the U.S. should focus on promising less and delivering more to build local resilience.

Coordination Begins at Home But Extends Far Beyond: A coordination deficit exists across sectors, agencies, and donors that impedes effective U.S. assistance in crisis and conflict. Formal structures and rules of engagement are helpful but insufficient, as highlighted in Iraq and Haiti. Pre-existing relationships between local authorities and donor counterparts had an outsized influence on more successful coordination in contexts like Somalia and Nepal. In the Philippines, a clear-eyed appreciation for the roles and value-additions of different agencies, along with personnel on the ground who valued interagency collaboration and working adaptively to respond to local needs, aided coordination in the Philippines.

Investing in the Capacity of Local Partners, Rather than Parallel Systems: U.S. assistance has a colossal vulnerability: it channels minuscule funding through local governments, relying on NGOs and other implementers. This status quo provides no clear exit strategy that allows for a sustainable transition of financing and oversight of programs to counterparts. Insistence on parallel systems means that when the U.S. pulls back, investment and capacity vanish with it, as in Iraq, or never take root, as in Haiti. America has made more gains in contexts like Nepal, Sierra Leone, and the Philippines, where patient investment in relationships and local capacity have helped civilian and military authorities better withstand and recover from crises or conflict.

This paper aims to answer three critical questions:

- How does the U.S. government deploy humanitarian assistance in crisis and conflict?

- To what extent does the U.S. government coordinate its efforts with other international and U.S. actors in the same theater of operation?

- In what ways does U.S. humanitarian assistance intersect and work synergistically with peacebuilding and longer-term development-focused efforts?

Defense U.S. Department of Defense

EAP East Asia and Pacific

ECA Europe and Central Asia

EU European Union

HDP Humanitarian, Development, Peace

LAC Latin America and Caribbean

MENA Middle East and North Africa

NGO Non-governmental Organization

NSS National Security Strategy

ODA Official Development Assistance

OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

PRC People’s Republic of China

SSA Sub-Saharan Africa

State U.S. Department of State

Treasury U.S. Department of Treasury

UN United Nations

U.S. United States

USAID U.S. Agency for International Development

USG United States Government

2. Strategic Context: The HDP Nexus from Concept to Operation

2.1 The Concept: Connecting Symptoms with Root Causes

2.1 The Impetus: The Need for a New Way of Working

2.2 The Practice: OECD Recommendations on Operationalizing the HDP Nexus

3. Operational Realities: U.S. and International HDP Financing by the Numbers3

3.1 A Global View of HDP Financing Across Donors4

3.2 United States: A Top Donor Across the HDP Nexus

4. Delivering Along the HDP: Key Players, Approaches, and Case Studies

4.1 Other External Players in Crisis and Conflict

4.2 The Role and Approach of the United States in Crisis and Conflict

4.3 Case studies: Four Profiles of U.S. Assistance in Crisis and Conflict

5. Take-Aways: Lessons from U.S. Assistance in Crisis and Conflict

Lesson 1: A Long-Term Strategic Approach Grounded in Realism, Aimed at Resilience

Lesson 2: Coordination Begins at Home But Extends Far Beyond

Lesson 3: Investing in the Capacity of Local Partners Rather than Parallel Systems

1. Introduction

The need to coordinate humanitarian, development, and peace efforts is evident in crisis and conflict contexts. Nevertheless, actors across these three dimensions have operated separately: funding and implementing their respective activities in relative silos. Increasingly, there are concerns that this status quo may be untenable. Crises have intensified and become more protracted (OECD, 2023). Disasters and non-state conflicts occur more frequently (GDAR, 2022; Palik et al., 2021). Together, these trends exacerbate the vulnerability of countries to shocks, particularly for the world’s most fragile states (Fund for Peace, n.d.).[2]

In parallel, suppliers of short-term emergency relief and long-term development assistance are growing weary and disillusioned about the ability of their funding to make much difference in contexts that struggle to break free from the vicious cycle of poverty, conflict, and instability. This raises the possibility that traditional sources of foreign aid will become less predictable and lower in volume amid political pressures in donor countries. Moreover, the persistent question remains about balancing responsiveness in times of crisis with maintaining the long view needed to deploy all types of aid—humanitarian, development, and peacekeeping (HDP)—in ways that optimize results and increase the likelihood that countries can become more resilient.

In the United States, these considerations have been at the forefront of discussions about the passage and implementation of the Global Fragility Act. However, they are visible as an undercurrent of national security strategies across the last five presidential administrations. These dynamics are not unique to the U.S., though as the world’s largest bilateral humanitarian assistance provider, the challenge feels particularly acute here.

Close allies like Germany and France and leading multilateral venues like the United Nations (UN) and the Organization for Economic and Development (OECD) are grappling with similar questions, creating an opportunity to learn together. The HDP Nexus, conceptualized at the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit, provides a common framework across partners to discuss this problem set. The resulting agreement stated that the solution to protracted crises involves meeting immediate humanitarian needs and reducing risk and vulnerability (Nguya & Siddiqui, 2020).

This chapter uses the HDP Nexus as a backdrop to surface lessons for future U.S. assistance in crisis and conflict. To conduct this analysis, we employ a mixed methods approach: (i) in-depth background interviews with policymakers and practitioners; (ii) desk research on assistance strategies, policies, and practices; and (iii) quantitative data on state-directed official development assistance (ODA) efforts collected by AidData and reputable third-party data providers.

Section 2 provides an overview of the HDP Nexus from concept to operation. Section 3 follows the money: examining how the U.S. and other donors supply financial assistance in contexts of crisis and conflict. Section 4 assesses how the U.S. coordinates and delivers assistance in these contexts globally and with a deep-dive look at four illustrative case studies. Section 5 concludes by surfacing several forward-looking lessons and takeaways from this retrospective analysis.

2. Strategic Context: The HDP Nexus from Concept to Operation

The term HDP Nexus is relatively new, but the recognition that crisis and conflict are connected to long-term development has been an essential facet of discourse on international assistance since the 1960s. As the UN General Assembly in 1960 deliberated solutions to hunger in poorer countries, member nations asserted that while distributing surplus quantities of food in the short term was necessary, the “ultimate solution…lay in an effective speeding-up of economic development” (Jackson, n.d). The following year, the first “United Nations Development Decade” broadened beyond material needs and included improving social conditions (UN, n.d.). The 1970s explored additional linkages, as the World Food Conference in 1974 argued that the world food crisis also had implications for universal human rights (Jackson, n.d.).

Amid a proliferation of armed conflicts and civil wars, peace and security occupied a more prominent position in development discourse in the 1990s and the 2000s (Jackson, n.d.). The 1997 UN Agenda for Development laid the groundwork for a multidimensional view of “peace, economic growth, environmental protection, social justice, and democracy.” With the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals, the UN identified peacebuilding as crucial to ending conflict but instrumental to helping countries achieve global goals (MDG Fund, n.d.). With the arrival of the 2015 UN Sustainable Development Goals, the growing appreciation of the role of peace in facilitating long-term development and resilience was evident in the adoption of goal 16, promoting peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development (Lindborg, 2017).

The 2010s saw the rise of terms such as fragility, risk, and resilience to explain the need to help countries with weak political institutions build internal capacity to withstand shocks, reduce vulnerability, and maintain hard-won development progress. In 2011, the World Bank’s World Development Report highlighted that investments in long-term development activities (e.g., access to justice and job creation) were critical for fragile states to break out of vicious cycles of conflict (Lindborg, 2017). The International Dialogue on Peacebuilding and State Building similarly called for donors to take the long view, considering inclusion, equity, justice, and livelihoods critical for fragile states to transition from conflict to peace (ibid).

2.1 The Concept: Connecting Symptoms with Root Causes

The HDP Nexus concept emerged from the disaster relief field. Aid workers were frustrated at responding to symptoms instead of addressing the root causes of disasters. Perhaps because of its origins in the humanitarian sector rather than the larger international assistance community, there is no common understanding of its nature, scope, and operational relevance. The shift in emphasis from disaster relief to applications in peace and security contexts added to the concept’s ambiguity. At times, peace refers to security concerns and violence reduction. At other times, it refers to a broader concept of stable institutions. Here, we use a narrow definition of security related to personal and state safety, leaving areas such as food (in)security as part of humanitarian or development aid depending on the context.

The terminology has evolved rapidly. Initially, the terms emphasized disaster: “linking relief, rehabilitation, and development”, the “emergency-development continuum,” or the “disaster-development continuum.” More recently, the term HDP Nexus (or Triple Nexus) has been used by the UN, its agencies, and the OECD. The United States government (USG) has a long history of considering “relief-development coherence” and “stabilization” as an important transition between conflict and development, as well as understanding the root causes of “fragility” to move from crisis response to preventive, long-term resilience building. It more recently adopted the term “HDP coherence,” though this is less prominent than the other terms.

2.1 The Impetus: The Need for a New Way of Working

At the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit, governments and organizations reflected on a new normal: the volume, cost, and length of crises were expanding in ways that strain development and humanitarian-focused actors alike. This led to a renewed emphasis on humanitarian and development actors working with local counterparts towards collective outcomes: “reducing risk and vulnerability…as installments toward [achieving] the Sustainable Development Goals” (OCHA, 2017). By implication, participants knew that the community would need to “overcome long-standing attitudinal, institutional, and funding obstacles” (ibid). To this end, they embraced a New Way of Working, which emphasized improved coherence, complementarity, and closer alignment, where appropriate, in four areas: (i) analysis, (ii) planning and programming, (iii) leadership and coordination, and (iv) financing.

Despite the agreement around the concept, the challenge remains to practically operationalize this approach institutionally and financially when it is known that coordination often depends on informal relationships between actors rather than formal channels. Moreover, the different actors do not necessarily have the same immediate priorities or incentives. For example, humanitarian providers have an immediate goal to fulfill humanitarian needs, which may or may not be at odds with the government, particularly in conflict. Multilateral development banks, on the other hand, see the recipient governments primarily as clients. Bilateral actors, including but not limited to the U.S., each have foreign policy interests that influence their priorities, preferences, and actions.

2.2 The Practice: OECD Recommendations on Operationalizing the HDP Nexus

The OECD developed a 2017 Humanitarian Development Coherence Guideline to support the Development Assistance Committee members in translating the outcomes of the World Humanitarian Summit into a framework for action. In 2019, the Recommendations on the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus was adopted by member countries at their Senior Level Meeting. The OECD developed the recommendations with its members and multilateral and civil society partners. The OECD’s emphasis on advancing the HDP Nexus in the work of members was likely influenced by the sobering reality that more countries were experiencing violent conflict in 2016 than the last three decades, and nearly half of people living in extreme poverty lived in fragile states. The recommendations addressed three dimensions (see Table 1): coordination, programming, and financing (OECD, 2022a).

Table 1. OECD Recommendations on the HDP Nexus

|

Coordination |

||

|

||

|

Programming |

||

|

||

|

Financing |

||

|

In 2022, the OECD released an Interim Progress Review to assess how its members implemented the HDP recommendations. The Interim Progress Review identified areas of progress and bottlenecks. It proposed nine areas where its members could focus attention in the future: (i) adopt best-fit coordination in every context; (ii) implement inclusive financing strategies; (iii) promote HDP Nexus literacy; (iv) empower leadership for cost-effective coordination; (v) use financing to enable and incentivize desired behaviors; (vi) integrate political engagement within the collective approach; (vii) invest in national and local capacities and systems; (viii) use the HDP Nexus to integrate other policy priorities; and (ix) enlarge the roundtable of stakeholders.

To date, the OECD recommendations remain the most widely used set of principles around the HDP Nexus, adopted by its members, UN agencies, and multilateral development banks (OECD, 2022b). These strategic-level discussions about how to work across the HDP Nexus are particularly relevant to the United States as a long-standing member and leader within the OECD and a comparatively large financing supplier across the nexus.

Individual USG agencies have worked to translate the principles of HDP Nexus into action. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), for example, issued a series of documents for this purpose, including a toolkit for practitioners, a toolkit for donors, and a note for USAID implementing partners (USAID 2022a, 2022b, and 2022c). These documents function as roadmaps and include decision-making tools, institutional policies and procedures, and financing models recommended by USAID to support HDP coherence. However, as discussed in Section 4, most HDP Nexus adjacent policy and legislative frameworks in the U.S. are framed around “fragility-to-resilience” (Ingram & Papoulidis, 2017).

Other donors have made efforts to incorporate the HDP Nexus in their strategies. For example, the World Bank Group highlighted changes in the ways it works in settings of fragility, conflict, and violence in its strategy for 2020-2025 (World Bank, 2020). Some highlights of this strategy include the acknowledgment that its approach has evolved from a focus on post-conflict reconstruction to addressing challenges across the spectrum of fragility, the scaling up of volume and types of financial support to those countries, and the recognition of the private sector at the center of a sustainable development model in these settings.

3. Operational Realities: U.S. and International HDP Financing by the Numbers

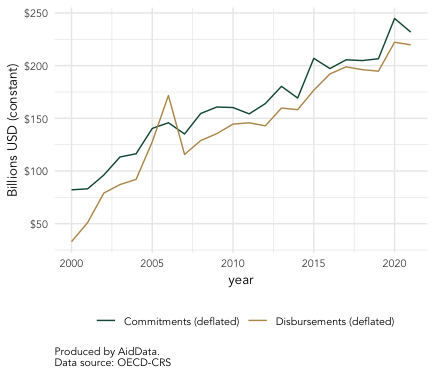

The constant calls for additional aid to fill in the growing needs across the globe may lead to the impression that aid has been stagnant, but that is not the case. ODA[3] has been on a steady path of growth over the past several decades and reached its peak in 2020 with US$245 billion in commitments (Figure 1), according to data reported by donors to the OECD’s Creditor Reporting System database. However, the rate of growth is far from that needed to close the financing gap to reach global agendas such as the Sustainable Development Goals, which was estimated at US$3.9 trillion in 2020 (OECD, 2023). The U.S. plays an outsized role in crisis contexts because it is and has consistently been the single largest provider of humanitarian aid globally and also due to the leadership role it often plays in these scenarios.

Figure 1. Official Development Assistance From All Donors Over Time (2000-2021)

3.1 A Global View of HDP Financing Across Donors

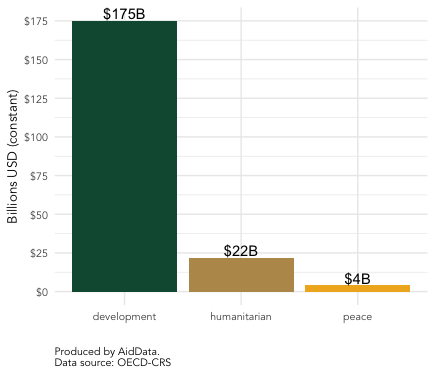

Between 2012 and 2021, ODA was concentrated in long-term developmental aid (87 percent),[4] with a small subset dedicated to humanitarian (11 percent) or peace (2 percent) purposes, on average. We define each category based on OECD sectors. Humanitarian aid includes projects classified under “humanitarian aid” and “emergency response.” Peace aid comprises the “conflict, peace, and security” sector. Long-term developmental aid includes all the remaining sectors.

This translates into a yearly average across OECD-reporting donors of US$4 billion to peace efforts, US$22 billion to humanitarian efforts, and US$175 billion to development (Figure 2).[5] The significant difference across the three streams likely reflects the reality that while all low and middle-income countries need long-term development aid to a certain degree, humanitarian aid or peace aid are typically only allocated to countries in settings of fragility or conflict. Moreover, crises can look very different across countries. Peace aid is more likely distributed in conflict contexts in least-developed countries. In contrast, middle and upper-middle-income countries are more likely to be able to use the fungibility of money to fund emergency needs, but that would lead to gaps elsewhere, which may or may not be filled by international donors.

Figure 2. Average Annual Official Development Assistance by HDP Sector (2012- 2021)

The share of ODA dedicated to humanitarian efforts has increased over the past decade, from 7 percent in 2012 to 15 percent by 2021, likely in response to the growing frequency of crises. Nevertheless, the relatively small share of humanitarian and peace-focused funding reinforces the importance of closer engagement and coordination with long-term development providers early on. The fact that the humanitarian sector has primarily pushed the concept and discussions around the HDP Nexus is a major stumbling block in moving from lip service to daily practice, ensuring buy-in and engagement from the security and development sectors.

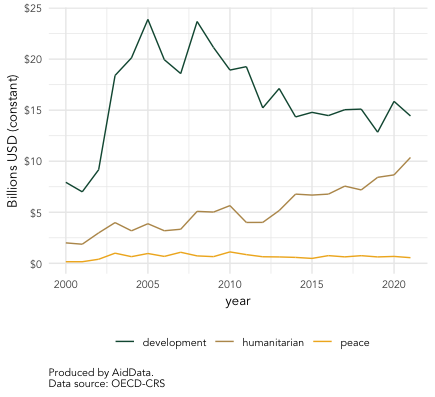

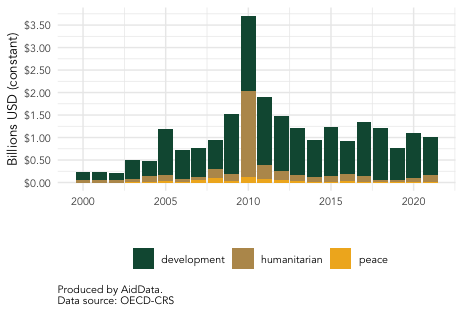

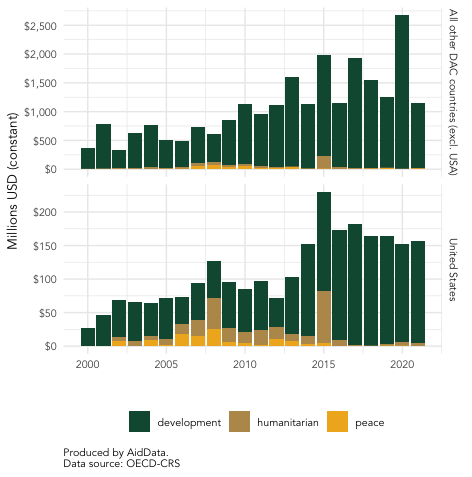

3.2 United States: A Top Donor Across the HDP Nexus

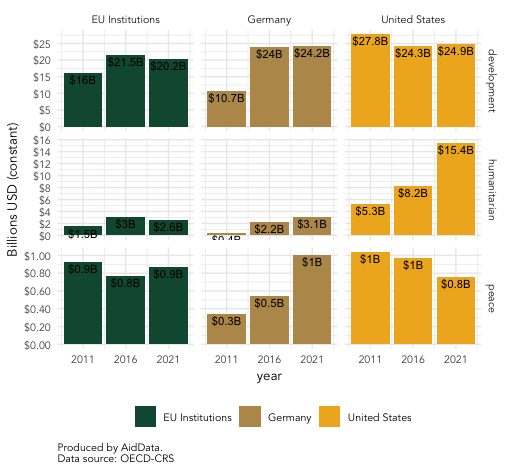

The U.S. has a significant role in ensuring coherence and coordination across the humanitarian-peace-development nexus. Over the past two decades, it has consistently been the largest provider of humanitarian aid. The U.S. primarily drove the global increase in humanitarian aid in recent years. As a case in point, humanitarian-focused aid from the U.S. government (USG) grew two-fold from US$8.2 billion in 2016 to US$15.4 billion by 2021. Moreover, humanitarian aid is sometimes an “easier sell” to American policymakers and reaches bipartisan support with greater ease.

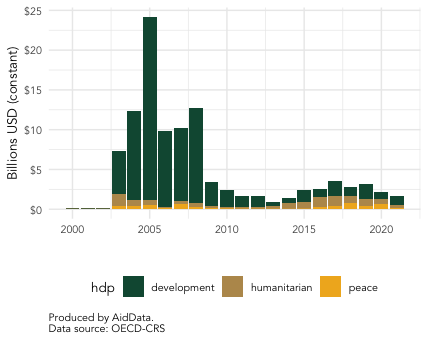

Figure 3. United States Official Development Assistance by HDP - dollars (2000-2021)

Figure 4. Select Donors' Official Development Assistance to HDP sectors Over Time (2011, 2016, and 2021)

Notably, the U.S. is not only a huge player in the humanitarian field, but it is also a top supplier of ODA focused on long-term development assistance and peacebuilding. Figure 3 shows how the U.S. compares to other leading aid suppliers like Germany and the European Union (EU). The U.S. is typically the first or second largest provider of developmental aid (with Germany) and among the three largest providers of peacekeeping aid (with Germany and the EU).

The apparent prioritization of long-term development aid could partly reflect the data reporting system and how narrowly we define humanitarian aid or peace aid. Nevertheless, the drivers may be more substantial and linked to the nature of these different types of aid. For example, development aid goes through a lengthier budget approval process, while humanitarian and peace aid is urgent.

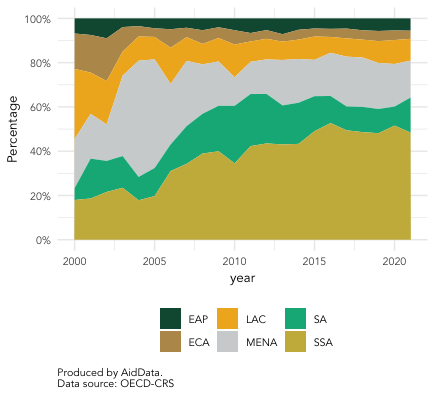

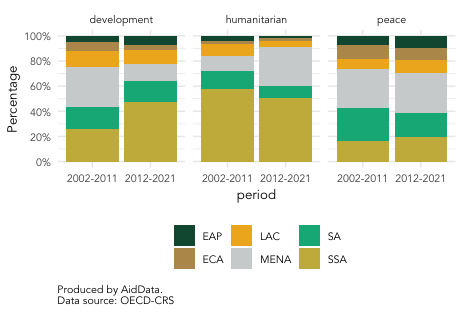

Over the 21st century, U.S. foreign assistance has progressively shifted away from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, where it concentrated most of the investment in the early 2000s, and towards Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). This geographic pivot reflects more extensive commitments to Iraq early on since 2003 that have gradually reduced until the 2010s (Figure 5). In 2021, nearly half of the USG's ODA was directed to SSA. Most of this increase was distributed across the region. However, some countries stand out in receiving an outsized increase in ODA from the U.S., namely Ethiopia, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Figure 5. United States Official Development Assistance by Region, Percentage (2000-2021)

It would be tempting to assume that the pivot from the Middle East and North Africa to SSA explains why we see a decline in peace-focused assistance (a traditional U.S. emphasis in its engagements in the Middle East) alongside the uptick in humanitarian assistance dollars over the same period (a prominent feature in U.S. engagements in Africa). Counter to expectation, this does not appear to be the case. Taking a closer look at the two regions, SSA has seen a decline in its share of humanitarian aid from the U.S., while the Middle East and North Africa saw an increase. The growth of long-term development aid was the more consequential trend that catapulted SSA ahead of the Middle East and North Africa as a top recipient of U.S. assistance. Also notable is the slight decrease in the share of ODA going to Europe and Central Asia (ECA) across all HDP sectors (Figure 6).

Figure 6. United States Official Development Assistance by Region and HDP Sector

4. Delivering Along the HDP: Key Players, Approaches, and Case Studies

There are many players engaged across the HDP Nexus, both within and outside of the USG. The relevant USG actors include the Department of State (State), USAID, the Department of Defense (Defense), and–in some cases–private sector implementers. State is at the forefront regarding diplomatic negotiations with key counterparts; Defense is often directly engaged in crises with a security or military component. In most cases, USAID’s role is more of a service deliverer than a negotiator. However, that often varies according to the individual leadership in-country offices.

In the recipient (or counterpart) country, there may also be multiple players: national government agencies (if there is a functioning public sector), corresponding local government offices (mainly if the crisis or conflict is heavily concentrated in a particular subnational hotspot), along with local civil society and private sector actors, depending on the specific case. Traditionally, the national government was seen as the leading actor. However, increasingly, those familiar with fragile state contexts observe a trend towards greater fragmentation with more and more actors involved. This adds complexity to the coordination challenges. Subnational authorities or private sector actors in specific regions of a country play an outsized role where the central government has weak capacity or its political legitimacy is contested.

4.1 Other External Players in Crisis and Conflict

Players outside the USG include multilaterals–particularly the UN and multilateral development banks, other bilateral development partners, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and private sector actors. Between development partners, the UN is often best positioned to be a convener and a neutral player in a crisis context. However, there are cases in which the USG takes the role of the convener since it can be seen as a bilateral with “skin in the game” in many scenarios. The World Bank and International Monetary Fund traditionally took more of a backseat role in contexts of crisis or conflict, as they often stop engagement with a country once the instability level crosses a threshold. However, that has been changing recently, as the World Bank is engaging more with crisis countries (e.g., West Africa) and making combatting fragility more central in its work. Other bilaterals play different roles according to the recipient country.

Furthermore, there is increasing participation of non-traditional development actors. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Russia are increasingly involved in crisis and conflict, along with longer-term development. The PRC is typically seen as more heavily focused on long-term development and commercial engagement but has played prominent roles in supplying emergency relief in far-ranging crises from earthquake response to COVID-19. It also has been building deeper relationships with foreign militaries, border patrols, and law enforcement through training, technical assistance, finance, and in-kind support. Less is known about its use of private military and security contractors. However, these are reportedly an increasing phenomenon to help the PRC and counterpart governments secure investments along the Belt and Road, mainly when these are located in areas of civil or political unrest.

The Kremlin is seen as comparatively less involved in humanitarian assistance and long-term development but is an essential player in the security sector, for better or worse. It has been supplying peacekeepers in frozen and hot conflict zones throughout Eastern Europe and Eurasia. It has long served as a spoiler in channeling financing and training to separatist groups in disputed territories in that same region, well before the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 (Custer et al., 2023).

Farther afield, the Kremlin’s involvement has been more through private military and security contractors such as the Wagner Group in countries like Mali and the Central African Republic. Ostensibly, the Kremlin’s involvement in these contexts is more of a wildcard, sometimes with the potential to alleviate instability and other times inflaming it, depending upon its interests and relationship with a country's political leadership. The Kremlin’s involvement can also have cascading repercussions for other development actors, such as the case in Mali, where Russia was seen as having exploited France’s exit from the country to tip the scale in its favor.

4.2 The Role and Approach of the United States in Crisis and Conflict

Even before the events of September 11th, 2001, President Bill Clinton argued in the 1999 national security strategy that weak or failed states represented a clear and present danger with far-reaching ripple effects (e.g., mass migration, famine, disease, violence) affecting regional security and America’s interests (NSS, 1999). This early warning became impossible for U.S. policymakers to ignore after the 2001 terrorist attacks. President George W. Bush’s two national security strategies highlighted weak or failed states as among the top dangers to U.S. national interests because of their susceptibility to “exploitation by terrorists, tyrants, and international criminals” (NSS, 2006). The congressionally-mandated 9/11 Commission reflected a bipartisan consensus that deterring terrorism required more than combatting symptoms but addressing root causes of extremism (e.g., inequality, poverty, isolation) (USIP, 2019). President Barack Obama continued this refrain with different phrasing in his 2015 NSS, viewing “fragile and conflict-affected states” as among the top risks to America’s national interests (NSS, 2015).

By the late 2010s, U.S. policymakers increasingly agreed that fragility was a problem that required not only a reactive but a preventive strategy to resolve (USIP, 2019). However, what to do about it was less clear: a 2016 assessment by the Fragility Study Group underscored this point, saying that “across the USG, there is no clear or shared view of why, how, and when to engage with fragile states” (Burns et al., 2016). Congress agreed, instigating the formation of a “Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States'' in 2017, tasked with defining how the U.S. should help countries build resilience to “resist extremism on their own” (USIP, 2019).

In its final report, the Task Force put forward three recommendations: (i) a strategy and shared framework to prevent underlying causes of extremism as a “political and ideological problem” developed with interagency and in-country partners; (ii) a “strategic prevention initiative” aligning resources and operations to operationalize the joint strategy, with an emphasis on interagency coordination and decentralized execution at the embassy level; and (iii) a “partnership development fund” for agencies, allies, and the private sector to pool resources and operational efforts in support of the new prevention strategy (USIP, 2019).

In parallel, the executive branch under the administration of President Donald Trump conducted a Stabilization Assistance Review in a coordinated effort of State, Defense, and USAID. However, observers familiar with the process described it as being driven from within agencies by career bureaucrats beginning in 2017 rather than pushed from the top down by political appointees. The aim was to articulate a “new framework to best leverage [U.S.] diplomatic engagement, defense, and foreign assistance to stabilize conflict-affected areas” (SAR, 2018).

Like the Task Force report, the Stabilization Assistance Review identified the need for a “singular, agreed-upon strategic approach” to stabilization across the interagency, defined it as a transitional step between immediate crisis and long-term development,[6] and proposed a 7-part framework to operationalize it (ibid). Nevertheless, without high-level political support, institutionalized authorities, and demarcated resources to work differently, the Stabilization Assistance Review lacked teeth and staying power.

One of the most consequential steps in operationalizing the HDP Nexus within U.S. assistance efforts was the passage of the Global Fragility Act,[7] passed with bipartisan support in Congress and signed into law in 2019. The Global Fragility Act is imperfect but integrated many ideas from the Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States and the Stabilization Assistance Review. Taking the long view, it sought to deter root causes of conflict and extremism before they occur rather than wait for them to arise, providing funding to do so (Graff, 2023).

The Act provided for funding of US$1.15 billion envisioned for the first five years, including up to US$200 million a year for a Prevention and Stabilization Fund[8] and US$30 million a year for a complex Crisis Fund (Yayboke et al., 2021). It mandated an interagency approach among key USG players (e.g., USAID, State, Defense, Treasury, among others). The Global Fragility Act also emphasizes the importance of flexibility, learning, and adaptive management to prevent violent conflict in dynamic contests (ibid).

However, the Global Fragility Act is off to a slow start. The Trump administration did not submit a strategy detailing how it would implement the law until December 2020, choosing not to name the five countries or regions to be included in the pilots (Welsh, 2022). It was not until April 2022 that the Biden administration announced a “prologue” to the 2020 Global Fragility Act strategy and selected four countries (e.g., Haiti, Libya, Mozambique, Papua New Guinea) and the coastal West Africa region (inclusive of Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea and Togo) to be included in the first phase (DoS, 2022). The 10-year implementation plans for each participating country and region were not released until February/March 2023, nearly another year later (Graff, 2023).

These delays may be partly attributed to the need to navigate a complex political transition between two administrations but also signal the daunting size of the task. Thinking holistically and comprehensively about the long-term causes of conflict requires different skills and the involvement of greater numbers of stakeholders than before—across the interagency and within the pilot countries (Graff, 2023). The high degree of consultation with groups affected by or involved in the conflict throughout the development of the implementation plans is laudable. It will be critical to their ultimate success, even at the expense of time (ibid). Moreover, the Global Fragility Act necessitates a profound culture shift among agencies and partners used to rapidly mobilizing and deploying resources to respond quickly to an emergent crisis, as opposed to incremental, sustained change that is “measured not in days and weeks, but in years and generations” (Mines & Devia-Valbuena, 2022).

Nevertheless, additional questions remain. How quickly will U.S. embassies be able to access and spend money to drive forward progress against the Global Fragility Act plans? To what extent will the activities undertaken via the implementation plans represent new and innovative thinking about the nature of the problem versus a repackaging of old ideas and practices? In tackling underlying drivers of conflict and instability, how will projects balance the need for strategic patience in waiting for long-run, slow-burn projects to bear fruit with the pressure to demonstrate measurable progress to Congressional and executive branch leaders back in Washington?

4.3 Case studies: Four Profiles of U.S. Assistance in Crisis and Conflict

In this section, we look into four countries in different contexts of fragility or conflict in the 2000s: Haiti, Nepal, Sierra Leone, and Iraq. Haiti was selected as an example where there had been continuous engagement of the international community, compounded by post-earthquake response, but where development failed to take off, leading to severe donor fatigue. Nepal was picked as a post-conflict country, as it overcame a civil war from 1996 to 2006 and one prone to natural disasters. Sierra Leone, another post-conflict country, represents a different case in which the U.S. did not take the lead in post-conflict recovery and reconstruction, given the countries’ closer ties to the UK as a member of the Commonwealth. Lastly, Iraq was selected as a case where the U.S. had a direct military engagement.

Haiti: A Failed State and NGO-land Navigate Intersecting Crises

Haiti is a country grappling with “intersecting crises”: a battered economy from COVID-19, fuel price spikes after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, successive natural disasters, a dysfunctional healthcare system, and a political leadership vacuum (Mines & Devia-Valbuena, 2022). Food insecurity and armed kidnappings are on the rise. At the same time, the government has yet to recover from the dissolution of its parliament and the removal of justices under the administration of President Jovenel Moïse, who was assassinated in July 2021 (ibid). Susceptible to natural disasters, Nepal has minimal resilience to withstand and respond to shocks (Seelke & Rios, 2023).

The combination of these factors has made Haiti the 11th most fragile state in the world, and questions about the government’s legitimacy and capacity to deliver development for its people persist (Fund for Peace, 2022; Seelke & Rios, 2023). By October 2022, the political and security situation had deteriorated to the point that Acting Prime Minister Ariel Henry requested that the UN send a foreign security force to “reestablish control and enable humanitarian aid deliveries” that had been disrupted by gang blockades (Seelke & Rios, 2023).

Rather than a new phenomenon, the roots of Haiti’s vulnerability date far back in a history filled with political, economic, and social instability. However, the 2010 earthquake brought new devastation to the Caribbean country, straining the government's capacity to manage rising humanitarian needs. With a magnitude of 7.2, the earthquake’s epicenter hit 15 miles southwest of the capital, Port-au-Prince, causing an estimated death toll of 316,000, displacing 1.3 million people, incurring damages between US$7.8 billion and US$8.5 billion, and severely impairing the Haitian government’s capacity to operate.

In the aftermath, Haiti received international aid to support its recovery and reconstruction efforts. In 2010 alone, Haiti attracted nearly US$3.8 billion in ODA, compared with a yearly average of roughly US$680 million in the ten years prior (Figure 7). Since then, ODA to Haiti has remained elevated, averaging nearly US$1.2 billion annually. The U.S. was among the largest donors to Haiti in the aftermath of the earthquake, and now it disbursed US$1 billion in fiscal year 2010 and US$301.8 million in 2022 (FA.gov).

Figure 7. Global Official Development Assistance to Haiti by the HDP sector

USAID was the lead agency responsible for much of the U.S. post-earthquake response in Haiti, with a significant emphasis on reconstructing the country’s decimated health, power, transportation facilities, and public housing (GAO, 2023; FA.gov). Between 2010 and 2020, USAID bankrolled US$2.3 billion in post-earthquake infrastructure activities in Haiti (GAO, 2023). However, the agency’s experiences underscore the difficulty of assisting in crisis and conflict contexts. In a 2023 review of USAID’s infrastructure projects, the Government Accountability Office cited overly rosy cost and time projections, inadequate mission staffing, lack of strong local partners, inadequate systems to track and assess project progress, and limited government capacity as significant impediments to success (GAO, 2023).[9]

These factors meant that many USAID-funded infrastructure activities in Haiti were chronically over budget, delayed, and vulnerable to cancellation or suspension due to insufficient funds (ibid). USAID's greatest difficulty appeared in big-ticket construction activities, as it performed relatively better in delivering more health and agriculture projects (Charles, 2023).

In parallel, State focused its funding on Haiti to strengthen the Haitian National Police Force (Seelke & Rios, 2023). The Government Accountability Office (2023) reports that the efforts of State’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs have “achieved mixed results” due to an overemphasis on outputs (e.g., trainings delivered) rather than outcomes (e.g., improved investigation capacity). It may also be the case that State’s focus on counternarcotics, the prison system, and professional management of the police force were insufficient (ibid). The steady uptick in gang violence, crime, and kidnappings in Haiti since the earthquake is a powerful justification for skepticism as to the efficacy of these efforts.

Due to limited government capacity, aid to Haiti had primarily been channeled through NGOs, even before 2010. This was expedient and understandable in light of the desire to ensure that Haitians got timely access to life-saving and life-enhancing assistance they could not rely on their government to provide. However, this short-term mindset had the unintended longer-term consequence of perpetuating weak public sector institutions and setting up parallel NGO-run systems that can only be sustained by donor financing. For this reason, Haiti has been given the unfortunate moniker of “Republic of NGOs” (Ramachandran, 2012).

Against this inauspicious backdrop, it is unsurprising to see that over a decade following the 2010 earthquake, Haiti’s governing institutions remain feeble, and there is a vacuum in local political leadership, such that there is little domestic pressure to compel international donors to coordinate their efforts, at least in a formal sense. As a result, what little coordination is done on an ad hoc basis. In the past two decades, the number of donors active in Haiti has steadily increased—from under 20 in 2000 to 56 as of 2021 (Figure 8). An informal “Core Group” of leading donors (including representatives from the U.S., Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Spain, the European Union, the Organization of American States, and the UN) has “shaped international responses to key events in Haiti” since 2004 (Seelke & Rios, 2023).

In 2010, an Interim Haiti Recovery Commission was launched with great fanfare at a conference of donors in March 2010. The Commission had high-level leadership in co-chairs Jean Bellerive (Prime Minister of Haiti) and former U.S. President Bill Clinton, and a stated commitment to work with local partners to ‘build back better’ (UN, n.d.; Abdessamad, 2023). Nevertheless, it soon became apparent that not all was going well, as “less than 2 percent of promised reconstruction aid” was delivered by July 2010 (UN, 2010). Eighteen months later, the commission ended as abruptly as it started, with an “ambitious array of projects…few finished or financed” and insufficient political buy-in to extend its mandate (NY Times, 2012). Contrary to donors’ stated commitments to work through local partners and systems, in the first two years of the crisis response, the percentage of aid disbursed through the Haitian government and non-governmental actors was paltry: less than 10 percent and 1 percent, respectively (UN, n.d.).

While not unique to Haiti, fragmentation among donors and an even larger number of implementers was particularly detrimental. Despite the large volume of assistance and the number of players involved, there has been limited progress in helping Haiti transition from a protracted political and humanitarian crisis to a more stable trajectory toward long-term development. To make matters worse, international donors have become fatigued by the fruitless exercise of spending more money with little to show for it, exacerbated by incoherence in the assistance community and unstable domestic political situation (including the assassination of the sitting president, Jovenel Moïse, in 2021).

Figure 8. Number of unique donors and channels in Haiti by year (2000-2021)

Haiti is often cited as an example of failure in international assistance efforts, plagued by a “short-term vision and fleeting political support” (Mines & Devia-Valbuena, 2022). Haitians’ response to UN efforts has been mixed: the peacekeeping mission from 2004 to 2017 was credited with restoring temporary stability but reviled for its role in spreading cholera and rampant sexual and human rights abuses (Seelke & Rios, 2023). Since 2019, the UN Integrated Office in Haiti has been charged with assisting the government in restoring stability, security, and the rule of law (ibid); however, its effectiveness has not been helped by rotations of UN humanitarian missions on “six-month mandates” that promote a short-term mindset (Mines & Devia-Valbuena, 2022).

Nevertheless, it remains a priority for donors. Haiti was the first country with a joined-up country planning process across the HDP Nexus in 2015. It has been included as a pilot country for the UN’s New Way of Working and on the EU’s Nexus pilot initiative. In those, the thematic areas of the pilot are climate resilience, peace, human security, food security, and economic resilience. The U.S. Congress passed the Haiti Development, Accountability, and Institutional Transparency Act in 2022, which mandated that America would “support sustainable rebuilding and development” and work in ways that “recognize Haitian independence” and promote legitimate democratic institutions (Seelke & Rios 2023). Agencies were required to monitor and report on their progress (ibid).

In 2022, the USG announced Haiti as one of the selected partner countries to pilot the development of a longer-term ten-year strategy to prevent conflict and promote stability under the first implementation phase of the Global Fragility Act (DoS, 2022). The 10-year implementation plan for Haiti released earlier this year emphasizes making the government more “responsive to Haitians’ basic needs” and “increasing trust in public institutions” in ways that encourage citizens to participate in Haiti’s civic and political processes (DoS, 2023). The security and justice sectors will be an early focus in the first phase, reflective of Haiti’s severe physical security challenges in light of rising rates of crime and violence (ibid). In phase two, the USG will work with Haitian counterparts to improve economic opportunities and access to justice essential to longer-term efforts to mitigate future conflicts (ibid).

The 10-year plan is not an innovative take on achieving progress in Haiti; however, it presents an opportunity to focus renewed political attention, dedicated financing, and participation of a wider cross-section of donors and in-country stakeholders to turn things around after years of limited progress. However, this may be easier said than done, given Haiti’s historical challenge of relying on government authorities that are “highly centralized” at the national level, narrowly representative of only “a small constituency” of urban elites, and disconnected from the rest of the country (Mines & Devia-Valbuena, 2022). It is also unclear whether and how Congressional restrictions on channeling aid via the central government, as well as earmarks and directives directing aid to reforestation and the basic needs of Haitian prisoners, will affect agencies’ abilities to support Haitian-led solutions in line with the Global Fragility Act.

Nepal: A Disaster-prone, Climate-vulnerable Country, Slowly Building Resilience

As a least-developed country, Nepal shares some of Haiti’s challenges. In the early 2000s, Nepal was a fledgling democracy emerging from a civil war. Despite holding two “free and fair elections,” political institutions were still fragile (Stivers & Staal, 2015). Twenty-five percent of Nepal’s population lived in extreme poverty, and this was an improvement after a multi-year effort in collaboration with international donors (ibid). Even today, political instability is underscored by a near constitutional crisis in 2021. Nepal is vulnerable to natural disasters and is one of the “most earthquake-prone countries in the world” (INSARAG, 2016). It is also caught in a problematic geopolitical position such that Nepalis describe their landlocked country as a “yam between two boulders,” squeezed on both sides by assertive powers jockeying for regional influence: China and India (Custer et al., 2019).[10]

Nevertheless, Nepal was better prepared than Haiti to withstand and manage the devastating 2015 earthquakes. The Nepali government and international partners had anticipated the likelihood of a catastrophic disaster for several years prior. This afforded the players a critical asset: time to prepare. The National Risk Reduction Consortium was formed in 2009 to facilitate collaboration around five “flagship priorities for sustainable disaster risk management” (Cook et al., 2016). Donors and Nepali counterparts set up coordination mechanisms and operating frameworks for disaster management and conducted joint preparedness exercises to simulate response in emergency scenarios (ibid). USAID had invested in building Nepal’s emergency response capabilities—from earthquake-resistant construction to prepositioning supplies for rapid action (Stivers & Staal, 2015).

This recognition that good governance and resilient systems benefited Nepal’s long-term development and the best defense in a humanitarian crisis may explain why ODA to Nepal has consistently increased over time, mainly in the development sector (Figure 9). Comparatively, aid to humanitarian and peace efforts has decreased over time, with the U.S. and all other OECD donors on average financing less than US$10 million a year since 2019. What is less clear is whether insufficient attention is being paid to humanitarian needs, given the persistent food insecurity affecting approximately 3.9 million people, or 13 percent of the country’s population (World Food Program, 2022).

2015 was the last year in which Nepal would receive a large stream of humanitarian aid. This coincided with the international response to a 7.8 magnitude earthquake that April, followed by a 7.3 magnitude aftershock in May, that catastrophically affected 22 of 75 districts (CFE-DM, n.d.). The earthquakes exacted a horrible toll on a vulnerable country: “killing about 9000 people, destroying basic infrastructure, and displacing tens of thousands in districts near the Kathmandu Valley” (Lindborg, 2015; Reid 2018). Beyond the immediate loss of life and infrastructure, the disaster triggered US$9 billion in economic losses (Cook et al., 2016).

Figure 9. Official Development Assistance Financing to Nepal, U.S. versus All Other Development Assistance Committee Donors (2000-2021)

Within hours of the 2015 earthquake, the international community rallied around Nepal: 34 countries sent civilian responders, 18 countries also supplied military search and rescue, and 70 countries contributed bilateral aid, along with participation from countless non-government and multilateral actors (Cook et al., 2016). Together, it is estimated that these first responders “treated 27,390 people, evacuated 3,493 people, and delivered 966 tons of relief supplies,” all coordinated by the Nepali Army and civilian agencies (CFE-DM, n.d.). Nepal received US$309 million for humanitarian efforts from OECD donors, 25 percent of which was from the U.S.

Nepal’s regional neighbors also pledged their support, including financing from India (US$1 billion) and China (US$483 million) (Cook et al., 2016) and in-kind support from Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Bhutan (Bishwal, 2015). Beijing, in particular, was a high-visibility player (e.g., sending search and rescue teams, along with tents and medical supplies) and a big spender, committing US$483 million in financing to support the reconstruction of schools, hospitals, and resettlement houses (Rauhala, 2015; Tiezzi, 2015; Custer et al., 2019). USG officials testifying before the House Foreign Affairs Committee on lessons learned from Nepal reported that there were several positive examples of informal bilateral coordination with non-OECD partners, such as India’s willingness to assist the U.S. deployment via “overflight clearances, use of airfields, and eased visa restrictions” (Biswal, 2015).

Unlike Haiti, the Nepali government was much more engaged and emphatic about the need for emergency responders to work in coordination with the local authorities.[11] The Nepali Army coordinated the contributions of foreign military responders and search and rescue activities under the Multinational Military Coordination Center (CFE-DM, n.d.). In parallel, the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs worked with Nepal’s National Emergency Operations Center and the Ministry of Home Affairs to play a similar coordination role on the civilian side (ibid). An “integrated planning cell” between the two was established to “deconflict support operations” and ensure a coherent response (ibid). Meanwhile, the NGO Federation of Nepal served a similar function to integrate the efforts of national and international organizations working in the same geographical area (Cook et al., 2016).

This is not to say that communications and coordination among these disparate civilian, military, bilateral, and multilateral actors was seamless. Some actors bypassed official government channels in a race to deliver supplies using what essentially became parallel systems (Cook et al., 2016). Nepal’s one international airport became a chokepoint as uncoordinated arrivals of international urban search and response teams overwhelmed the system (INSARAG, 2016). Civilian responders concentrated around main transportation arteries (e.g., highways and accessible roads), making it difficult for the Nepali government to ensure equitable relief supplies for all needy communities (Cook et al., 2016). Meanwhile, at times, Nepali authorities “lost track of the whereabouts of foreign military teams,” which provoked concern (ibid).

Seeking to exert greater control, the Nepali government issued a “one-door policy” that imposed restrictions on non-governmental agencies and individuals distributing emergency support in isolation from the government. To ensure efficient and equitable distribution of search and rescue services, the Nepali government also assigned different partners to specific geographic sectors for their operations (e.g., India in the West, China in the North, and the U.S. in the East) (CFE-DM, n.d.). Nevertheless, some partners blatantly ignored these assignments, instead looking for “more profitable sites” with the potential for greater media exposure (INSARAG, 2016).

The Nepali government defended the one-door policy as critical to sustaining social cohesion in the country (Melis, 2022). However, research has shown that aid allocation in the framework of that flash appeal was less responsive to need than ethnic and political biases. Municipalities near the Nepalese capital and those frequently receiving general development aid were more likely to attract projects (Eichenauer, 2020). This scenario highlights the need to carefully navigate these complex crises in balancing the humanitarian desire to respond quickly and by any means to alleviate humanitarian suffering with the longer-term state-building objective of boosting the capacity and credibility of local state actors to deliver for their people.

Reflecting on the lessons learned, the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command emphasized the importance of pre-existing relationships based on mutual respect, trust, and complementarity in making Nepal a successful disaster response effort (CFE-DM, n.d.). This included interagency relationships benefiting from “high familiarity among U.S. civilian and military teams due to previous planning and senior leader activities,” as well as U.S. embassy personnel on the ground who ensured coherence across the contributions of various agencies (ibid). In the eyes of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, this foundation facilitated Defense’s contribution of military personnel to a Joint Humanitarian Assessment Survey Team working with USAID’s Disaster Assistance Response Team (ibid). A long history of military-to-military relations and security cooperation created trust and familiarity between U.S. and Nepali military personnel on the ground.

Similarly, USAID has worked on long-term development projects with civilian Nepali counterparts for many years across government agencies and non-governmental actors. Illustrative projects included a 15-year partnership with the Kathmandu-based National Society for Earthquake Technology to improve earthquake education, awareness, and preparedness, as well as collaboration with local, regional, and national disaster management agencies in Nepal since 1998 to build capacity for medical first response, search and rescue, and hospital preparedness for mass disaster under the Program for the Enhancement of Emergency Response (Stivers & Staal, 2015). In addition to disaster risk reduction and preparedness, this also included more general social and governance sector programming.

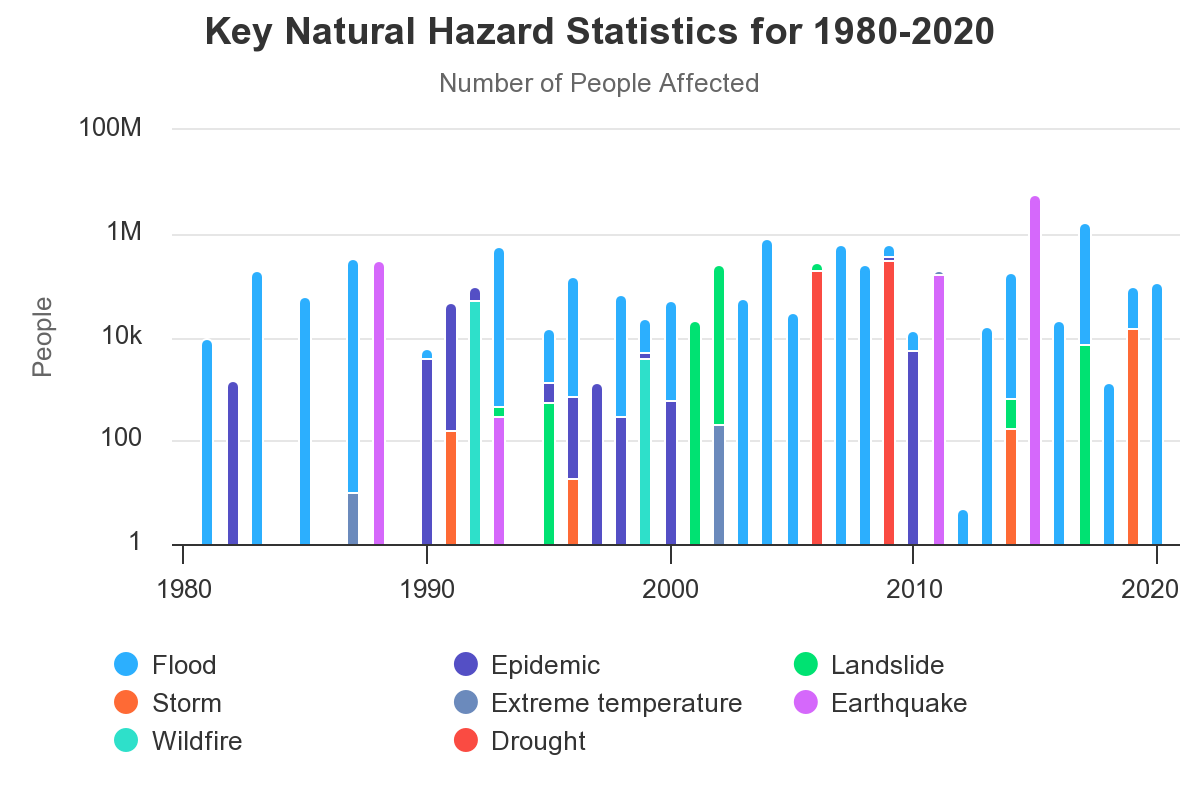

Nepal has not been hit by another earthquake of similar magnitude since 2015; however, the country’s disaster vulnerability is not limited to earthquakes. Its diverse geo-climatic system renders the country vulnerable to many different natural events: floods, landslides, and droughts (Figure 10). In the years after the 2015 earthquakes, hundreds of thousands of people were affected by floods and droughts, with the lack of humanitarian aid likely to have been felt by the poorest. Even though the international community has been providing development aid, the U.S. and its allies must be aware that stepping away from humanitarian efforts in a least developed country that has had to navigate its fair share of political instability poses risks of a vacuum left behind and threatens the gains from the development efforts.

Figure 10. Key natural hazard statistics for 1980- 2020 in Nepal

Source: World Bank’s Climate Change Knowledge Portal

Sierra Leone: a success story in post-conflict reconstruction working through partners

The civil war in Sierra Leone lasted from 1991 to 2002, and it ended after the introduction of a UN peacekeeping force to monitor the disarmament process and eventually a British intervention in the former colony and Commonwealth member. A slow withdrawal process took place for both British and UN peacekeeping forces. The UN completed the withdrawal of its peacekeeping force in 2005 and was succeeded by the United Nations Integrated Office in Sierra Leone.

Given the length of the conflict and the level of violence encountered (e.g., targeted property destruction, over 50,000 dead, substantial use of abducted child soldiers), Sierra Leone had extensive needs in the post-conflict reconstruction period. The EU and the United Kingdom focused on development aid initially, while the U.S. concentrated its aid on humanitarian efforts. Aid flows from other OECD members stayed relatively stable, while American aid dwindled after the first few years post-conflict (Figure 11).

Figure 11. U.S. and other Development Assistance Committee Official Development Assistance to Sierra Leone by HDP sector

In 2014, the Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Sierra Leone formally closed and transferred its responsibility to the UN Country Team, marking the end of over 15 years of UN Security Council-mandated peace operations in the country in what was seen as a “success story on steady progress” (UN News, 2014).

Soon after, Sierra Leone faced a major humanitarian challenge with an outbreak of Ebola that led the country to declare a state of emergency in July 2014. That led to a spike in humanitarian aid with nearly US$450 million in commitments that year alone, with the majority of it being from the United Kingdom and the United States (US$344 million and US$42 million, respectively). Since then, development aid has increased, and humanitarian aid dwindled again.

In mid-2023, the country had presidential elections. Despite concerns about electoral integrity and reports of intimidation, there was no violence or unrest in the aftermath. However, while external actors emphasize the importance of calm in these situations, there are concerns about accepting electoral results that lack integrity (Gavin, 2023).

Sierra Leone has closer ties to the United Kingdom, given its status as a former colony and a member of the Commonwealth. Consequently, it is also a country in which an ally took on the leadership in coordination, and the U.S. took a relative back seat in the reconstruction process. That makes it an interesting case study in which the reconstruction period is generally considered successful, yet typical challenges to development, such as governance and elections, remain difficult to overcome.

Iraq: “In-conflict” Reconstruction Following A Direct U.S. Military Engagement

In March 2003, when U.S. and coalition forces invaded Iraq, the intent was to topple the regime of President Sadaam Hussein and quickly transfer power to Iraqi authorities within 90 days (SIGIR, 2009). A month later, the Iraqi Army was defeated in the face of superior military forces; however, the “liberation” scenario that U.S. leaders hoped for proved optimistic (Cronin, 2007). Over 12 years, international donors and the Iraqi government would spend more than US$220.1 billion to rebuild the nation, carrying out these activities amid a violent and prolonged insurgency (Matsunaga, 2019a). Compared to Sierra Leone, Iraq is an example of “in-conflict reconstruction” (ibid).

Fateful early decisions by the Coalition Provisional Authority to demobilize the Iraqi Army and pursue de-Baathification had the unintended consequences of stoking discontent among former combatants without alternative livelihoods (SIGIR, 2009). Iraq lost essential technocratic capacity within its civilian government, a blow to a country that once was seen as among the more capably governed in the region as recently as the 1970s and 1980s (Matsunaga, 2019b). More ominously, the situation metastasized into a full-blown insurgency, creating the enabling conditions for the emergence of a “multinational terrorist organization” (Robinson, 2023).

Alongside the deteriorating security situation, international donors met in October 2003 to make commitments to support Iraq’s reconstruction. Together, thirty-eight countries and several multilateral organizations (e.g., the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the European Commission) pledged US$33 billion, over half of which was committed by the United States (US$18.6 billion) (Matsunaga, 2019b). The U.S. would ultimately spend much more—bankrolling up to US$60.6 billion by 2012, half of which went to “security-related expenditures” (ibid). Other donors had a smaller footprint, the largest of which included Japan, the World Bank, and the IMF (ibid). The largest funding source for Iraq’s reconstruction would come from the country’s resources, including oil production and exports (ibid).[12]

According to the OECD, Iraq received the highest amount of aid from international donors in 2005 with US$24 billion in ODA commitments, nearly all of it for development and primarily driven by the U.S. Aid to peace or humanitarian efforts never reached more than US$1.5 billion at any point between 2000 and 2021, even in the immediate aftermath of the war in 2003 (Figure 12). The International Reconstruction Fund Facility for Iraq was introduced to allow myriad donors to pool their resources into one trust fund with two windows managed by the World Bank and the United Nations, respectively (Matsunaga, 2019b). The trust fund was unique in two respects: it was the first jointly managed by the UN and World Bank, and it was the second-largest post-crisis up to that point (ibid). However, donors only channeled a token amount of money directed via the trust fund (US$1.86 billion).

Figure 12. Official Development Assistance to Iraq - by HDP sector (2000-2021)

At first blush, the large amounts of development aid (and comparatively limited peace and humanitarian aid) provided in a highly volatile security environment seem surprising. Initially, this was heavily influenced by the Coalition Provisional Authority’s “infrastructure-heavy reconstruction” strategy to restore order and restart the economy quickly (SIGIR, 2009). The Coalition Provisional Authority adopted a “maximalist approach to reconstruction,” preferring to tackle big-ticket projects that could transform a strategically important sector (e.g., oil, water, power) with a price tag to match (ibid). It convinced the U.S. Congress to fund this strategy to US$18.4 billion (ibid).

This proved to be easier said than done for several reasons. The normal difficulty of delivering reconstruction projects was compounded by severe physical insecurity. At the height of the violence, there were as many as 100 civilian deaths per day in 2006-2007. Iraqis and expats working on donor-funded projects made for attractive targets (Matsunaga, 2019b). The security situation created a substantial disconnect: those determining what projects to fund and where were cloistered in the heavily fortified Green Zone around the capital, at some distance from understanding what the average Iraqi needed (e.g., potable water, basic sanitation, electricity). The fact that decisions were often made unilaterally by the U.S. (or other donors) rather than in consultation with Iraqi government counterparts further reinforced this blindspot.

There was considerable pressure to approve and deliver reconstruction projects quickly, with insufficient thought to how they were designed and whether they could be sustained. In other words, the success metric became “burn rate” (getting money out the door) and supporting near-term tactical military objectives rather than lasting impact (communities able to use and sustain services or projects long after the U.S. exited the country). This led to misinvestments such as financing expensive water treatment stations over basic sewage systems, building community health centers with U.S. equipment that Iraqi doctors did not know how to use, and constructing schools without teachers or funds to maintain them. Moreover, completed projects were not always the same as quality projects, as evidenced by reports that some infrastructure had already begun to break down as early as 2005 (Matsunaga, 2019a).

From the perspective of winning hearts and minds, observers noted that large infrastructure projects also had the disadvantage of seeming too distant and slow-moving to matter to Iraqis. Instead, modest projects, funded by rapid response small grants programs to be responsive to community needs identified by local governance councils or create jobs, earned a more positive reception. These efforts also had the advantage of being faster to implement, with lower risks, and visible local impacts to build confidence, even on a small scale.

Although the U.S. was the largest donor, it was not unique in its tendency to go it alone. One of the enduring criticisms of Iraq's reconstruction overall was that it devolved into a set of disparate donor-funded projects, designed and delivered in relative isolation, rather than a coherent “national enterprise” (Wessel & Asdourian, 2022). Interestingly, and in contrast to Haiti, this state of affairs was not for the absence of a donor coordination mechanism. Iraq had not only one but four formal coordination mechanisms (Matsunaga, 2019b).

The Iraq Strategic Review Board reviewed and cleared new bilateral and multilateral reconstruction activities proposed by donors to “prevent duplication” of efforts (Matsunaga, 2019b). The International Reconstruction Fund Facility for Iraq was subordinate to this board, comprising two committees: one to facilitate coordination between the UN and World Bank windows, and the second to include other donors (Matsunaga, 2019b). UN agencies had their cluster coordination mechanism to ensure coherence with supporting thematic groups. Finally, the International Compact with Iraq initiative was formed in 2007 as a partnership between the Iraqi government, the UN, and the World Bank that “established benchmarks and mutual commitments” related to future reconstruction efforts (ibid).

Alas, this did not result in four times the level of coordination. The International Reconstruction Fund Facility for Iraq was beset by credibility and implementation challenges, especially for projects under the UN window, over concerns of limited oversight, conflict of interest, and chronic delays (Matsunaga, 2019b). Projects under the World Bank window fared modestly better. However, they suffered from poor integration with those implemented under the UN. They had frequent time overruns (ibid). Many donor coordination mechanisms had minimal to no engagement with Iraqi government counterparts and were inconsistent, initially starting strong and then tapering off in their meetings (ibid).

The degree to which donors prioritized engaging Iraqi authorities in decision-making was fundamentally shaped by the U.S. posture vis-a-vis Iraq’s governance. Initially, the U.S. was highly consultative with Iraqi authorities via the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance in the first few months following the invasion, when it anticipated a quick hand-off to Iraqi authorities (Matsunaga, 2019b). The formation of the Coalition Provisional Authority in May 2003 as the “de facto government” brought the opposite extreme, as its officials determined projects with minimal engagement with Iraqi institutions (ibid). Things shifted again in favor of more extensive donor coordination with local counterparts, as the Iraqi transitional government assumed the Coalition Provisional Authority’s responsibilities in June 2004 and then again during the leadership of U.S. General Petreaus and Ambassador Ryan Crocker (ibid).

Iraq is often raised by policymakers and practitioners as a scenario in which the United States entered into conflict without a clear plan on how to move toward state-building and resilience. In some respects, that might be true due to the overly rosy projections that the U.S. military would be able to withdraw within just a few short months after the invasion rather than “embark on a massive, open-ended nation-building project” (Robinson, 2023). Nevertheless, one could also argue that the problem was not only a lack of planning but also insufficient interagency coordination and consultation for all USG voices to be heard.

Matsunaga (2019b) cites several examples of thoughtful recommendations for long-term reconstruction and development emerging from exercises conducted at State (e.g., the 2002 Future of Iraq project), USAID (e.g., the Iraq Task Force), the Department of Energy (e.g., Steering Group on Iraq), and the National Security Council (e.g., the Interagency Humanitarian Working Group) in the lead up to the invasion. Meanwhile, SIGIR (2009) notes the striking absence of USAID Administrator Andrew Natsios from National Security Council meetings on Iraq until “long after the war began.”

5. Take-Aways: Lessons from U.S. Assistance in Crisis and Conflict

In this final section, we briefly reflect on emerging lessons learned to carry forward into future conversations about strengthening U.S. assistance to promote greater coherence, coordination, and outcomes along the humanitarian-peace-development nexus. In surfacing these lessons, we draw insights from the quantitative analysis of historical financing, country cases, desk research, and practitioner interviews.

Lesson 1: A Long-Term Strategic Approach Grounded in Realism, Aimed at Resilience

The ability of the U.S. to remain the leading humanitarian aid provider is a success. The U.S. alone contributed nearly as much as all other OECD donors combined in the decade between 2012 and 2021 (US$88 billion and US$89 billion, respectively). In 2021, it contributed US$15.4 billion compared with US$10.9 billion from all other OECD donors. However, there is limited recognition of the extent of American efforts to support all aspects of the HDP Nexus at home and abroad. This is a failure in U.S. strategic communication and triggers several different issues.

At home, it may be more challenging to galvanize funding support, while abroad, it is a missed opportunity for the U.S. to capture public diplomacy gains that could be used to advance its diplomatic interests. Moreover, the lack of domestic support for U.S. assistance abroad induces a short-term mindset focused on immediate tactical objectives rather than long-term strategic ones. This is partly a humanitarian instinct to alleviate immediate suffering, as in the Haiti case. This is also the pressure of spending money quickly in a dynamic situation, such as Iraq and Afghanistan. Naheed Sarabi, former Deputy Minister of Finance, asserts that the “short-termism and unpredictability” of international assistance contributed to failures in Afghanistan (Wessel & Asdourian, 2022).

The USG is often good at responding to crises in the short term. The Bureau of Humanitarian Affairs can be very effective in dealing with the logistics of moving goods worldwide. The Office of Transition Initiatives in USAID is an example of a tool that works well with its aim “to provide fast, flexible, short-term assistance targeted at key political transition and stabilization needs” (USAID, n.d.). However, there is a need for more flexible and adaptable funding in the transition between crisis response and development. Even more important, there is a need for a clear, realistic, and holistic long-term plan to achieve local resilience that allows the U.S. to safely withdraw and leave stability behind. This long-term perspective, paired with flexible and agile financing, should change the success metrics from how quickly the money is spent to how well it moves countries one step closer to resilience.

Long-term strategy should not be conflated with overly ambitious, unrealistic plans. It was the immodesty of reconstruction efforts in Haiti and Iraq that derailed progress and diminished donor credibility in the eyes of counterparts. A high volume of large-scale projects with hefty price tags may sound impressive, but only when donors follow through, which is easier said than done. This warning is equally relevant in the lessons emerging from Afghanistan, as noted by former Deputy Minister Sarabi, who argued that donors “need less ambitious plans…they should promise less, deliver more” (Wessel & Asdourian, 2022).

Lesson 2: Coordination Begins at Home But Extends Far Beyond

There is a consensus among U.S. practitioners and policymakers working along the HDP Nexus that coordination (or the lack thereof) across different sectors and actors is one of the main impediments to doing this well. Without a clear structure or standard rules of engagement, coordination can still occur, but more organically and often contingent upon the personalities involved and pre-existing relationships between the players. On the flip side, even in cases where the institutional setup may support coordination, it may still not be enough.

Iraq was a case where multiple formal coordination mechanisms were theoretically present. However, it was more of an exercise in form over function, as international donors primarily worked independently of each other and the government despite multiple mechanisms. Nepal was a context where the government’s desire to lead the disaster response effort and provide the mechanisms to facilitate coordination compelled donors to largely fall in line. However, USG actors in Nepal emphasized that formal coordination structures only go so far and that pre-existing relationships are critical to working well with interagency peers and host nation counterparts.

Formal coordination channels were relatively absent in Haiti and Somalia, with very different results. In Haiti, this led to disconnected projects across international actors. By contrast, in Somalia, it created the opportunity for organic coordination. Development, defense, and diplomacy (USAID, Defense, and State) worked jointly in a “microcosm” of the USG. Along with the spontaneous rise in coordination, institutional backing is also there, as concepts of sequencing and layering assistance are present in coordination meetings.

A crucial difference between Haiti and Somalia was the level and type of geopolitical interest, which may have factored into the degree to which donors emphasized coordinating and the willingness of USG representatives on the ground to assume this leadership role. The main interest of the U.S. in Haiti is tempered: given the country’s geographic proximity, U.S. leaders want to avoid spillovers of insecurity in the Western Hemisphere. The interests in Somalia are more complex and varied—the presence of a terrorist threat, geopolitical interests with oil and gas, and geographic positioning adjacent to some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes—which may increase its urgency and importance to make coordination a strategic priority.

Mindanao in the Philippines is another example of organic coordination between USAID, Defense, and the U.S. Joint Special Operations Task Force to deliver basic humanitarian assistance (e.g., building latrines, providing food) amid a long-standing armed conflict.[13] This case showcased another important takeaway about coordination: it is easier and more likely to occur when each player has something to bring to the table and a clear sense of what they need from the others.

Lesson 3: Investing in the Capacity of Local Partners Rather than Parallel Systems

The USG should recognize an inherent vulnerability across its broader development assistance portfolio. It channels a minuscule amount of funding through local governments, even in better-governed countries, instead relying heavily on local or U.S.-based NGOs and other implementers. Corruption and financial mismanagement in host governments are legitimate concerns and ones that Global South leaders share, according to surveys of public, private, and civil society elites (Custer et al., 2022). However, this status quo provides no clear exit strategy that allows for a sustainable transition of financing and oversight of programs to counterparts.