Catalytic Partnerships: Opportunities and Challenges in Mobilizing U.S. Private Sector Resources to Scale America’s Contribution to Development Overseas

Gates Forum II Background Research

Bryan Burgess and Samantha Custer [1]

AidData | Global Research Institute | William & Mary

November, 2023

Executive Summary

The private sector is one of America’s most underutilized assets to support sustainable economic growth and development in the Global South. In this paper, we examine how the private sector expands the total resource pool available to support economic growth and development worldwide, as well as the tools the U.S. government has used to engage these actors over the last 20 years. We surface five lessons learned to highlight the most persistent challenges to effective private sector engagement.

Be More Specific About Which Private Sector Actors to Engage Where, How, and Why. The USG should be more strategic in pursuing focused partnerships with disparate private sector actors in areas of their revealed interest: private foundations (fragile states, vertical funds, public health, environment), private voluntary organizations (humanitarian relief, peacebuilding, and conflict settings), and private companies (agriculture, power generation, telecommunications, healthcare, infrastructure, extractives).

Get More From Private Sector Partnerships with Better Data, Learning, and Success Metrics. The USG lacks reliable data on the value generated by private-sector partnerships across the interagency regarding leverage and additionality. Traditional tools to monitor and evaluate development assistance projects are also unsuitable for assessing the impact and effectiveness of non-traditional approaches such as blended finance and public-private partnerships.

Strategically Exploit Aid, Trade, and Investment as Force Multipliers for Global Development. There is minimal overlap between countries that receive American aid versus those that attract trade and investment. With additional resources and a clear mandate, trade capacity-building programs, regional investment hubs, and embassy deal teams, among other tools, could be the bridge builders in helping the USG synchronize its aid, trade, and investment for greater effect.

Reduce Byzantine Regulations and Duplicative Mechanisms that Deter Partnership. Procurement and reporting regimes such as the Federal Acquisition Regulations and the Section 653(a) budget process deter many would-be partners from engaging with the USG’s development agenda. A related concern was ensuring that the proliferation of new private sector engagement mechanisms across the interagency did not create confusion and frustration for would-be partners.

Reconcile How Localization, Risk Tolerance, and Private Sector Engagement Work Together. USAID’s localization commitments raise questions, from implementers concerned about lost access to valuable development assistance dollars to existing and prospective partners who interpret “localization” as synonymous with “increased risk” that threatens profitability. Agency leaders need to articulate how localization and private sector engagement are not at cross-purposes and can be mutually reinforcing. USG agencies and the private sector must learn to appreciate how each understands risk: public entities focus on transparency, procurement compliance, and project delivery, while the price sector looks at a spectrum of risk that could impact their commercial or financial position

This paper aims to answer three critical questions:

- How do private sector companies and philanthropies broaden America’s contribution to supporting development in low- and middle-income countries?

- What lessons can be learned from past U.S. government attempts to engage American private sector finance and expertise to amplify U.S. development assistance abroad?

- How might USG and private sector actors work more synergistically to scale the reach and impact of development assistance?

AGOA: Africa Growth Opportunity Act

BUILD: Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act

Defense: U.S. Department of Defense

DFC: U.S. Development Finance Corporation

FDI: Foreign Direct Investment

FTA: Free Trade Agreement

Gates: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

MCC: Millennium Challenge Corporation

NGO: Non-governmental Organization

ODA: Official Development Assistance

OECD: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

OPIC: Overseas Private Investment Corporation

PPP: Public-Private Partnership

PRC: People’s Republic of China

PVO: Private Voluntary Organization

State: U.S. Department of State

Treasury: U.S. Department of Treasury

U.S.: United States

USAID: U.S. Agency for International Development

USG: United States Government

2.1 U.S. Private Philanthropies as Direct Resource-Providers for Development

2.2 U.S. Nonprofits and For-Profit Companies as Direct Implementers of Projects

2.3 Foreign Direct Investment, Trade, and Finance as Indirect Growth Engines

3.1 Hedging Risk, Alleviating Uncertainties of Working in Developing Countries

3.2 Reducing Downsides, Improving Upsides for the Private Sector to Engage with the USG

3.3 Improving Business Climates and Market Potential for U.S. Investment and Trade

Lesson 1: Be More Specific About Which Private Sector Actors to Engage Where, How, and Why

Lesson 2: Get More From Private Sector Partnerships with Better Data, Learning, and Success Metrics

Lesson 4: Reduce Byzantine Regulations and Duplicative Mechanisms that Deter Partnership

Lesson 5: Reconcile How Localization, Risk Tolerance, and Private Sector Engagement Work Together

1. Introduction

U.S. state-directed development assistance is a drop in the bucket compared to the American economy, representing just 0.22 percent of the U.S. gross national income in 2022 (OECD, 2023b). One of America’s greatest assets and enduring attractions in the eyes of other countries is the vibrancy of its private sector—from companies and philanthropies to universities and non-governmental organizations. At home, these actors spur job creation and scientific innovation, build thriving communities, and improve lives and livelihoods. Abroad, the U.S. private sector can mobilize resources, implement projects, deliver services, and generate economic value to benefit the U.S. and counterpart nations.

The catalytic potential of crowding in private sector support for development is not lost on the U.S. government (USG). Some agencies cultivate private sector partnerships and launch sector- or region-specific initiatives to crowd in private capital and expertise. Others focus on reducing barriers to entry for U.S. private companies to export goods and invest in emerging markets. Deal teams within U.S. embassies pool interagency resources to help American companies win business abroad in ways that advance multiple national interests.

In this paper, we examine how the private sector expands the total resource pool of development flowing from the U.S. to the developing world and how this complements and supports American priorities. We assess the specific tools the USG has enlisted to engage the private sector across government-funded development assistance, using both the lens of regulatory authority and revealed priorities. We conclude with a discussion of outstanding issues for policymakers to consider as the U.S. looks to develop future private-sector engagements.

|

Note on Terminology: In this paper, we examine how U.S. private sector actors alone or in conjunction with the U.S. government employ grants, loans, and other debt instruments, along with in-kind and technical assistance, to support development in other countries. This includes grants and no- or low-interest loans, typically referred to as ‘aid,’ and loans and other debt instruments approaching market rates referred to as ‘debt’). We include humanitarian and long-term development assistance. For ease of reading, we have chosen to simplify our terminology and use the generic terms “development assistance” and “aid” as catchalls for these various and diverse instruments. However, in instances where the particular modality matters (i.e., grants versus loans), we use the more specific terms to avoid confusion. This paper adopts a broad definition of “private sector actor.” While conventionally focused on businesses, investment institutions, and other profit-generating enterprises, this paper also considers philanthropic organizations, private voluntary organizations, for-profit firms implementing USG programs, and investment promotion entities such as chambers of commerce. |

2. Key Actors and Complementarities: How Do U.S. Private Companies and Philanthropies Broaden U.S. Development Assistance in Other Countries?

The economic impact of the United States in the developing world is, at least partly, a story of the private sector. Private flows account for 90 percent of U.S. dollars reaching the poorest countries (Adelman et al., 2017). The largest U.S. philanthropies now give at the same volume as some governments and demonstrate to the world the generosity of the American people. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) matches U.S. investors' capital to business owners' needs, enables local innovation and entrepreneurship, and offers a sustainable funding source for countries to develop their economies.

The USG has a long history of turning to private entities to implement its aid programs (Norris, 2014). In 2022, 35 percent of the total USG aid portfolio was implemented by private partners, including faith-based organizations, enterprises, NGOs, networks, public-private partnerships (PPPs), and universities (ForeignAssistance.gov). This section examines three clusters of U.S. private engagement with developing countries: private philanthropies and the direct grants they fund; U.S. nonprofits and for-profit companies that directly implement USG-funded activities; and flows of FDI, trade, and commercial finance (Table 1).

Table 1. Illustrative Typology of the Diverse Ways the Private Sector Supports Development

|

Role(s) of the Private Sector |

Description |

|

Direct Resource-Provider for Projects or Programs within Developing Countries |

|

|

Philanthropic giving |

Provision of funding with no expectation of repayment but intended to support projects, programs, and organizations for a bounded period |

|

Concessional financing |

Provision of cash or credit with the expectation of repayment with no or low-cost financing |

|

In-kind donations |

Provision of goods, services, supplies, software, equipment, or facilities at no or defrayed cost |

|

Technical assistance |

Provision of specialized expertise (e.g., professional advice or support) |

|

Data and analytics |

Provision of valuable data or analytics to support service delivery for organizations or governments |

|

Convening power and networks |

Facilitating the formation and maintenance of partnerships, collaborations, or dialogues |

|

Knowledge and information sharing |

Facilitating the sharing or transfer of skills and insights relevant to development projects and policies |

|

Direct Implementer of Projects and Programs within Developing Countries |

|

|

Distribution/production of essential goods |

Delivering free or low-cost access to food, household supplies, or other goods targeting poor or marginalized communities |

|

Direct service delivery |

Delivering free or low-cost access to critical public services (e.g., health, education, sanitation) targeting poor or marginalized communities |

|

Training and capacity building |

Helping individuals and communities cultivate skills, knowledge, and capacity via education or vocational training at free or low-cost rates |

|

Research and evidence generation |

Producing knowledge and insights that support policymakers and practitioners |

|

Advocacy and standard-setting |

Awareness raising, lobbying, and negotiating for improved conditions |

|

Indirect Economic Engine of Growth within Developing Countries |

|

|

Foreign direct investment |

Creating access to capital to pursue profitable ventures with local companies |

|

Local job creation |

Generating new employment opportunities for local communities |

|

Local revenue generation |

Generating tax, trade, or tourism revenues that benefit the local economy |

|

Norm setting |

Contributing to policies and practices that create an enabling environment for private-sector investment |

Notes: Adapted from OECD (2016) and Vaes and Huyse (2015).

2.1 U.S. Private Philanthropies as Direct Resource-Providers for Development

In the years before the First World War, two private philanthropies—the Carnegie Endowment and the Rockefeller Foundation—promoted transatlantic peace and public health abroad, as well as advanced America’s interests in promoting international rule of law (Rietzler, 2011). The rise of a new set of players in the 1990s and early 2000s would be even more consequential. Eleven of 23 American grant-making philanthropies that report donations to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)were founded between 1990 and 2006 (Table 2).

Table 2. American Philanthropies Reporting to OECD’s Development Assistance Committee

|

Philanthropy Name |

Year Founded |

Giving Reported (2000-21), in millions |

Most Recent Reporting Year (in millions) |

Geographic Focus |

Focus Sectors |

Known Partnership with USG (Y/N) |

|

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation |

2000 |

$46,806.80 |

$4,635.30 |

Global |

Health, Education, Equality |

Y |

|

Mastercard Foundation* |

2006 |

$3,211.68 |

$1,288.34 |

Africa |

Youth Employment, Education, ICT |

Y |

|

Michael & Susan Dell Foundation |

1999 |

$1,926.69 |

$47.29 |

India, South Africa |

Education, Health, Family Economic Stability |

Y |

|

Bloomberg Family Foundation |

2006 |

$1,134.15 |

$297.33 |

Global |

Health, Education |

Y |

|

Open Society Foundations |

1993 |

$1,493.25 |

$380.96 |

Global |

Environment, Equity, Journalism, Rule of Law |

Y |

|

Susan T. Buffett Foundation |

1964 |

$1,406.60 |

$355.11 |

Global |

Population, Reproductive Health |

N |

|

Ford Foundation |

1936 |

$1,342.35 |

$306.19 |

Global |

Civil Society, Equity, Environment |

Y |

|

David & Lucile Packard Foundation |

1964 |

$797.56 |

$218.20 |

Global |

Environment, Health, Reproductive Rights, Education, Agriculture |

Y |

|

William & Flora Hewlett Foundation |

1966 |

$778.15 |

$179.41 |

Global, w/ emphasis on Africa |

Education, Environment, Equity, Governance, Economy and Society |

Y |

|

Bezos Earth Fund |

2020 |

$676.48 |

$354.16 |

Global |

Environment, Food |

Y |

|

Rockefeller Foundation |

1913 |

$641.50 |

$305.24 |

Africa/Asia |

Food, Health, Environment, Energy, Equity, Economic Recovery |

Y |

|

Conrad N. Hilton Foundation |

1944 |

$587.68 |

$148.08 |

Global |

Youth, Early Childhood Development, Refugees, WASH |

Y |

|

John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation |

1978 |

$565.72 |

$130.78 |

Africa/Asia |

Corruption, Environment, Criminal Justice, Journalism and Media |

Y |

|

Howard G. Buffett Foundation |

1999 |

$561.99 |

$105.19 |

Africa/Asia |

Food Security, Conflict, Public Safety |

Y |

|

Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation |

2000 |

$419.12 |

$106.19 |

Global |

Environment, Health |

Y |

|

Margaret A. Cargill Foundation |

2006 |

$269.38 |

$47.08 |

Global |

Environment, Culture, Disaster Relief, Quality of Life |

N |

|

Omidyar Network Fund, Inc. |

2004 |

$228.02 |

$33.19 |

Global |

Responsible Technology, Reimagining Capitalism, Cultures of Belonging |

Y |

|

Citi Foundation |

1998 |

$145.54 |

$20.98 |

Global |

Economic Opportunity, Financial Inclusion |

Y |

|

Arcus Foundation |

2000 |

$131.99 |

$20.50 |

Global |

Environment, Human Rights |

N |

|

MetLife Foundation |

1976 |

$122.53 |

$1.54 |

Global |

Economic Inclusion, Financial Health, Resilient Communities |

N |

|

Carnegie Corporation of New York |

1911 |

$114.65 |

$15.63 |

Global |

Education, Democracy, Security, Immigration |

N |

|

McKnight Foundation** |

1953 |

$24.98 |

$4.38 |

Global |

Culture, Food Security, Environment, Energy |

N |

Notes: *Mastercard Foundation is an American company with headquarters in Toronto. **McKnight Foundation announced that it now only gives impact investments internationally via fund vehicles. Source: OECD CRS (2023a). All figures 2022 Constant USD, Millions.

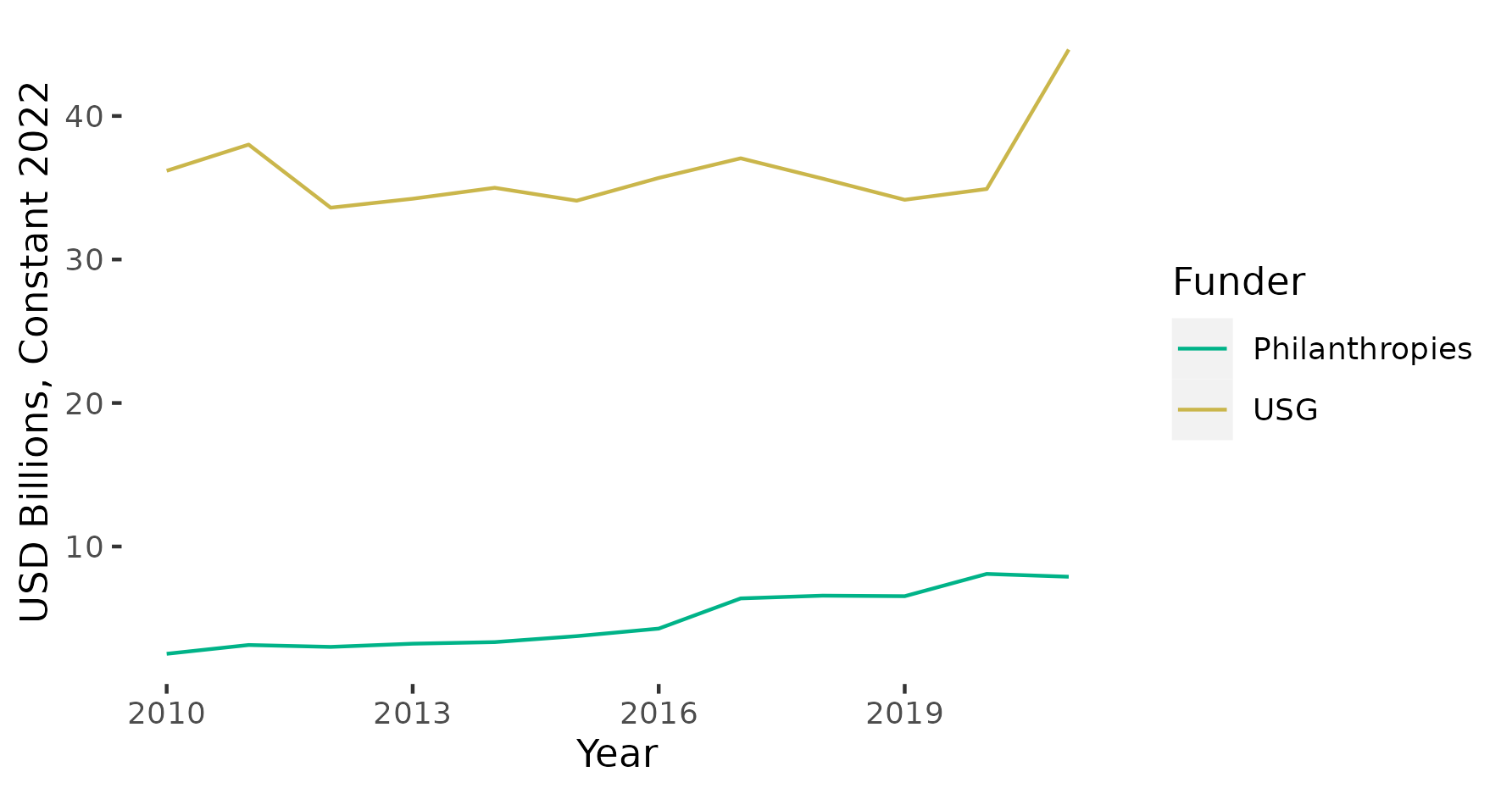

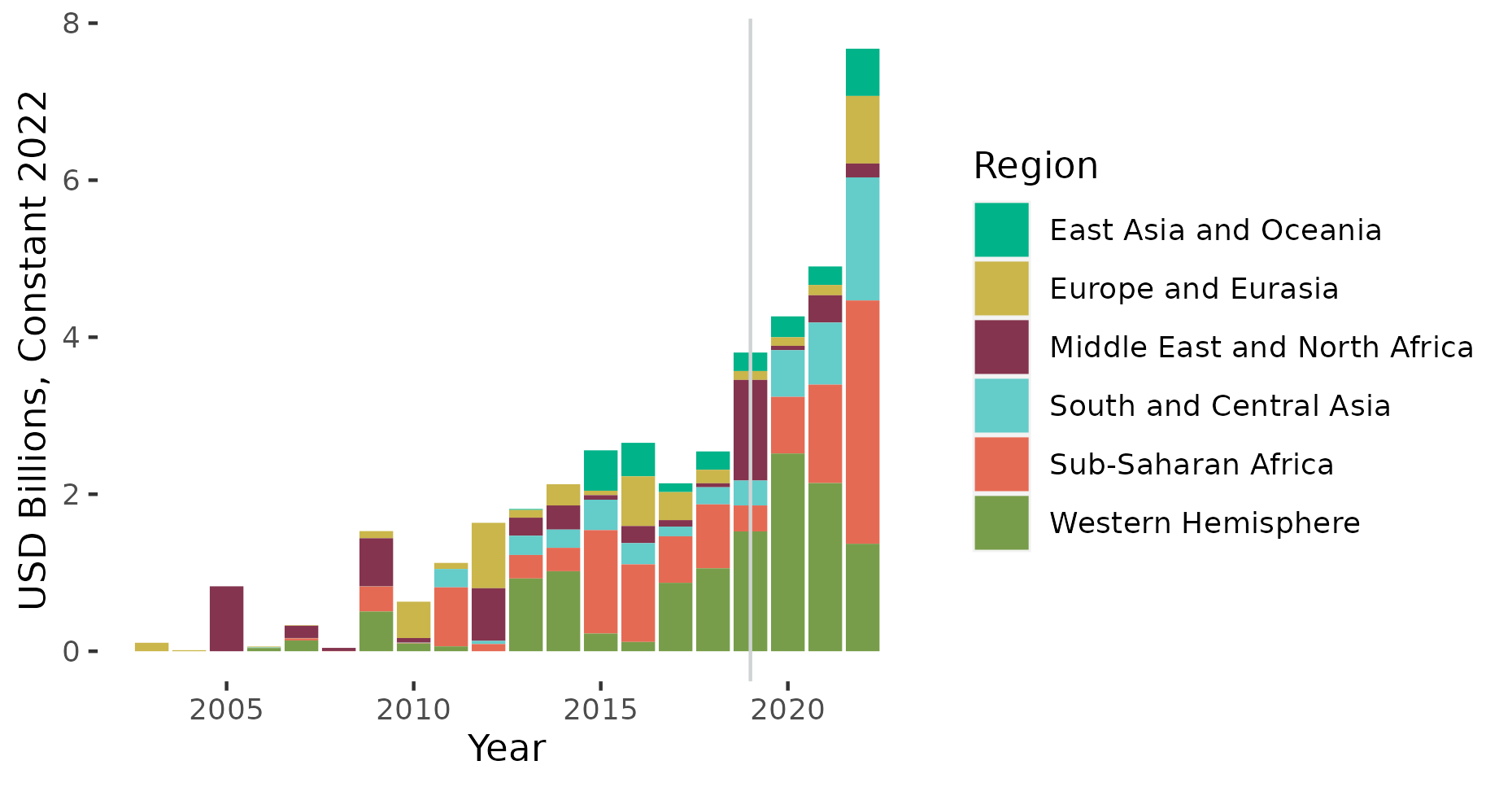

These 23 American private philanthropies have supplied at least US$58.8 billion in development assistance globally since 2010 (Figure 1). In 2021 alone, they gave US$7.9 billion, or roughly one-fifth of the value of USG disbursements the same year (OECD, 2023a). American philanthropies make an outsized contribution relative to bilateral and multilateral agencies and their peers in other countries. If we consider philanthropic organizations with sovereign nations, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Gates) would be the tenth largest donor in the world. This holds across all sectors, not just global health. The combined financial weight of American charities reporting to the OECD exceeded the next-highest Development Assistance Committee government, Canada, by US$2.9 billion. Moreover, most large private philanthropic donors came from the U.S. (OECD, 2023a).

Figure 1. U.S. Government versus Private Philanthropic Assistance Reported to the OECD Creditor Reporting System, 2010 to 2021

Note: The philanthropies value represents the sum of all U.S.-based philanthropic donors reported to the OECD system. Many of these donors only began reporting after 2017, likely under-reports the total philanthropic flows in earlier years. Source: OECD CRS (2023a).

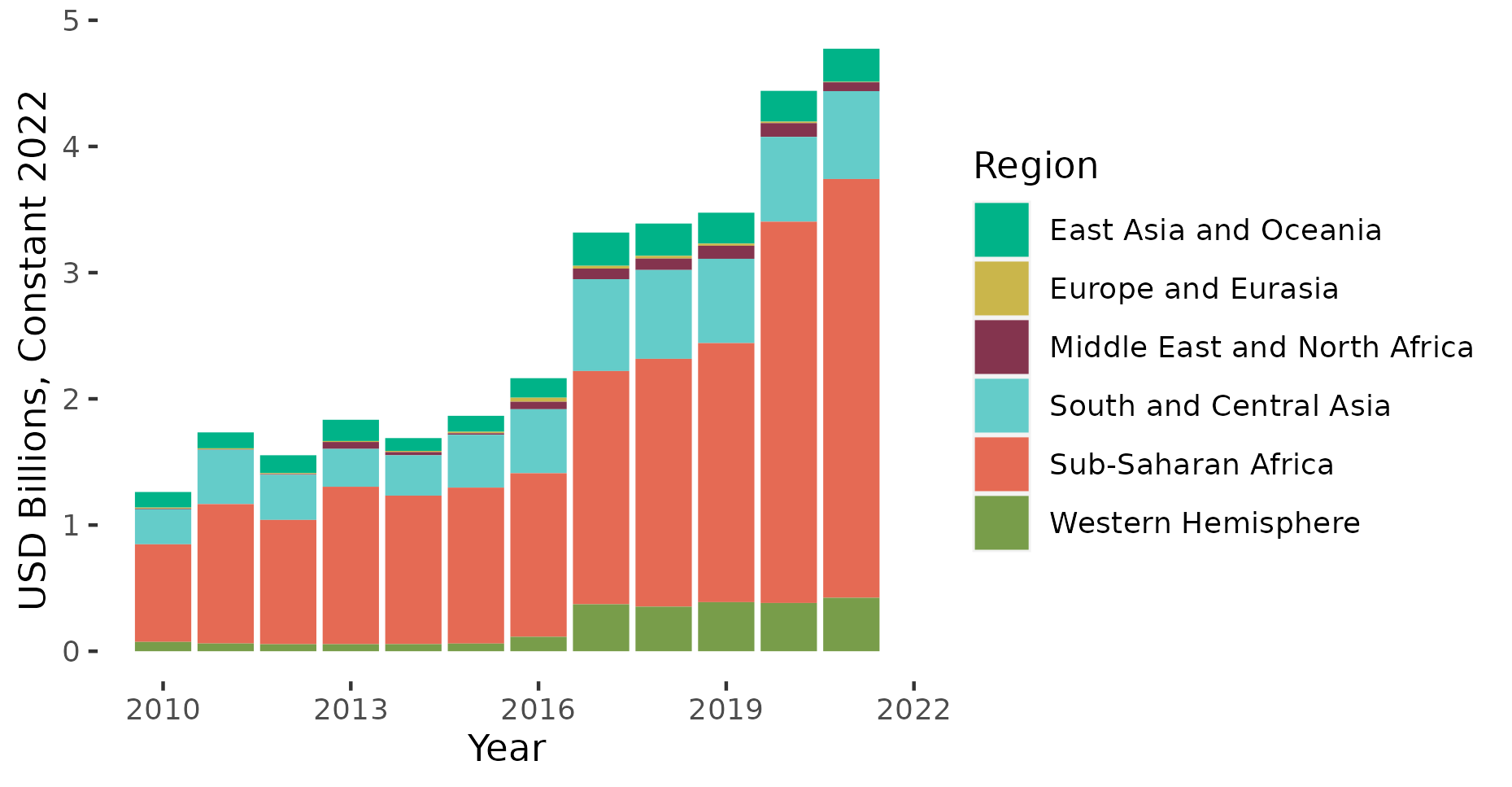

Two points of geographic convergence exist in the revealed priorities of these American philanthropies and the USG: India and Africa. American private philanthropies direct a higher share of funding (46 percent) to globally focused projects but a nearly identical proportion of financing towards Sub-Saharan Africa (34 percent) as their USG counterparts. India was the single largest country recipient of U.S. philanthropic funds and among the larger recipients of USG aid (36th); however, development funding for Africa still exceeds that for the Indian subcontinent. American private philanthropy, led by the Gates Foundation, is channeling billions to meet Africa’s health challenges, similar to the USG’s long-standing emphasis (and financing) on global health. Global and reproductive health attracts nearly two-thirds of all philanthropic funds to developing countries (63 percent).

Foundations have devoted comparatively fewer resources to other regions since 2010, except for a recent jump in funding to the Western Hemisphere in 2021 (Figure 2). This heightened interest in the region appears to be driven by environmental concerns and comes from a smaller cadre of foundations including the Bezos Earth Fund, Howard G. Buffett Foundation, Moore Foundation, Ford Foundation, and Open Society Foundation.

Figure 2. U.S. Private Philanthropic Assistance Reported to the OECD Creditor Reporting System, By Region, 2010-2021

Note: This chart excludes private philanthropic flows reported as cross-regional or global in intent, which exceeded US$3.1 in 2021. Source: OECD CRS (2023a).

The USG still orients relatively more of its aid budget (12 percent) than private philanthropies (1 percent) to working in the most fragile countries.[2] Yet, philanthropies do not shy away from fragile states. Considering only country-focused financing, the 23 organizations collectively contributed 4 percent of their budgets to the most fragile states, compared to 18 percent for the USG. By contrast, the rest of the U.S. private sector (approximated using FDI flows) prefers contexts that are not fragile or minimally fragile. U.S. private philanthropies might be more willing to work cooperatively with the USG in supporting development in fragile states, likely informed by their humanitarian missions to improve lives.

Special-purpose vehicles and vertical funds are an underexplored area for the USG to team up with U.S. private philanthropies to maximize the reach and influence of American development assistance efforts. The USG directs one in five aid dollars to such programs and funds managed by other international partners, often multilateral institutions. Private philanthropies' contribution is smaller; one in twenty of their aid dollars is directed via these modalities; however, these actors have outsized credibility and influence in niche areas, such as the Gates Foundation in global health or national statistics.

Another area for peer-to-peer learning and information sharing could be locally-led development, a stated priority for USAID and private foundations like the Hewlett Foundation. Private philanthropies also punch above their weight by providing US$3.0 billion in technical assistance, nearly on par with the USG at US$3.3 billion, between 2010 and 2021.

U.S. private philanthropies are also important extensions of American soft power when they engage with foreign publics and leaders. Corporate foundations and non-profit organizations bear American names and are often headed by influential American innovators. Of the 23 private philanthropies reporting to the OECD, many had some publicly disclosed experience in collaborating with USG agencies, most often episodic time-bound projects rather than long-standing formal partnerships. There are laudable exceptions.

In 2023, the Hewlett Foundation and Center for Global Development signed a Memorandum of Understanding with USAID to support the agency’s Evidence Localization Initiative in Africa (USAID, 2023j). The same year, USAID and the Gates Foundation pooled their resources. They announced a new Women in the Digital Economy Fund, with pledged contributions of US$50 million and US$10 million, respectively, over the next four years (USAID, 2023f).

Nevertheless, beyond co-financing or implementing discrete projects, more often than not, development assistance funded by USG agencies operates independently from American private philanthropic contributions at a strategic and tactical level. This status quo partly reflects a healthy U.S. tradition of minimizing state interference in the private sector. Moreover, government agencies and private foundations do not always see eye-to-eye due to differing political philosophies (across party lines) and missions. However, many experts interviewed for this study argued that limited partnerships between the public and philanthropic sectors were symptomatic of differences in incentives and cultures that make deeper partnerships challenging to form and sustain.

2.2 U.S. Nonprofits and For-Profit Companies as Direct Implementers of Projects

American philanthropic power extends beyond the 23 grant-making foundations that report their international giving to the OECD to a much larger universe of U.S.-based private voluntary organizations (PVOs). Since the 1940s, American PVOs have been critical in providing overseas charitable services and humanitarian assistance (McCleary & Barro, 2006; USAID, 2016b). These organizations vary in size.

According to Forbes’ 2022 list of America’s top 100 private charities, the 26 largest internationally-focused organizations each mobilized between $217 million and $2.2 billion in 2021 (Barrett, 2022). The list included charities associated with former U.S. presidents (e.g., Carter Center), faith-based groups (e.g., World Vision, Catholic Relief Services, Compassion International), and well-known secular organizations (e.g., International Rescue Committee, PATH, Save the Children, Population Services International), among others.

American PVOs are not monolithic in their relationship with the USG. While some organizations are entirely self-funded via private donations, others receive direct financial or in-kind support from USAID or other agencies to implement development assistance activities funded by the USG (USAID, 2016b). Collectively, the 26 Forbes list PVOs raised US$22 billion in revenues to support international needs in 2021 alone; 78 percent ($17 billion) was in the form of private donations (Barrett, 2022).[3] Combined with the OECD-reporting foundations that same year, this expands known private philanthropic flows to low- and middle-income countries to US$25 billion (55 percent of the value of what the USG disbursed in 2021).[4]

Although the USG directs foreign aid programs, it seldom implements activities directly, working instead procuring the services of a labyrinth of private sector actors including but not limited to PVOs via cooperative agreements, grants, and contracts (Morgenstern & Brown, 2022). These private sector actors also extend to “individual personal service contractors, consulting firms, universities, and public international organizations” (ibid).

This reliance on contracting private sector actors to implement USG-funded development projects is not new. It was a distinct feature of U.S. foreign aid from the start. As Secretary of State Dean Acheson explained President Truman’s signature Point Four Program back in 1952, “[it was] never meant to be just a government program, the entire effort…is carried out through private organizations. We do not have in the Government sufficient people to staff these operations…to give us all the ideas…which are necessary” (State, 1952).

The extent of the USG’s foreign aid ‘contract state’ has only proliferated, partly by design in tapping into specialized expertise that may not reside within government and partly by necessity, with the hollowing out of the professional core of USAID and other development agencies in the 1990s (Norris, 2014). This state of play led to the forming of a powerful and vocal constituency of American nonprofits and businesses that rely on large-dollar USG contracts to fuel international relief and development operations (Norris, 2014).

In 2021, 11 USG agencies channeled US$13.7 billion in development assistance dollars through 787 named private sector actors (i.e., U.S.-based entities or international organizations with a U.S. chapter) (ForeignAssistance.gov). Three agencies accounted for the lion’s share of disbursements to the U.S. private sector: USAID (47 percent), the State Department (44 percent), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (8 percent).

Private enterprises (48 percent) and PVOs (44 percent) were the most common recipients of these funds. U.S.-based universities also received modest funding (7 percent). Networks and PPPs each accounted for less than one percent. Not all of these actors are equal in the size of the dollars they attract: the average U.S. private sector actor managed US$12 million, but the top 20 USG funding recipients each managed between US$100-644 million (see Table 3).

Table 3. Top 20 US-Based Implementing Partners in USG Funding Received Fiscal Year 2021

|

US-Based Implementing Partner |

Organization Type |

USG Funding, 2021 (in USD2022 Millions) |

|

Catholic Relief Services |

PVO |

$644.65 |

|

Chemonics International, Inc. |

Business |

$581.18 |

|

RMGS, Inc. |

Business |

$380.51 |

|

Development Alternatives, Inc. |

Business |

$371.23 |

|

Abt Associates, Inc. |

Business |

$348.09 |

|

FHI 360 |

PVO |

$340.81 |

|

International Committee of the Red Cross |

PVO |

$308.16 |

|

Save the Children Federation, Inc. |

PVO |

$211.01 |

|

RTI International |

PVO |

$204.40 |

|

Columbia University |

University |

$173.25 |

|

Futures Group Global |

Business |

$169.69 |

|

ARD, Inc. |

Business |

$163.44 |

|

John Snow International |

Business |

$155.73 |

|

Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation |

PVO |

$150.03 |

|

Deloitte |

Business |

$140.01 |

|

Population Services International |

PVO |

$139.70 |

|

World Vision |

PVO |

$137.43 |

|

Consortium for Elections and Political Process Strengthening |

PVO |

$130.82 |

|

Pact World |

PVO |

$123.36 |

|

Alutiiq, LLC |

Business |

$111.01 |

|

Tetra Tech, Inc. |

Business |

$116.20 |

|

Jhpiego Corporation |

Business |

$114.71 |

Note: Disbursements via RMGS, Inc. and Alutiiq, LLC’s are partially redacted in the full ForeignAssistance.gov dataset, and were calculated based on aggregates presented via the website while all other values are calculated from project-specific data records. Source: ForeignAssistance.gov.

There is, of course, a much broader swath of U.S.-based private sector entities that partner with USG agencies—having received funding in previous years or supplying their financing and in-kind support to overseas development activities. To approximate this larger universe, we cross-referenced the U.S. private sector entities that received USG funding in 2021 with the list of organizations that voluntarily joined USAID’s partner directory. This yields a larger list of 1,398 PVOs, businesses, private foundations, and universities with headquarters in the United States that partner with USAID. Roughly three-quarters (77 percent) of these entities either received USG financing in 2021 (ForeignAssistance.gov) or reported that they had previously been a “prime or subprime recipient” of USAID funding (USAID, 2023).

Private sector partnerships can take other forms. American farmers supply “a portion of U.S. food aid, shipped overseas on privately-owned U.S. flag cargo ships” (Morgenstern & Brown, 2022). Companies provide donated goods, hardware, and software in support of USG assistance programs. Another important way U.S. private sector entities support development assistance is not merely as “paid implementers” but as co-financiers in joint projects with the USG in areas of shared interests (ibid.). Historically, some of the best examples of these private-sector partnerships have focused on specific sectors or grand challenges—from power generation and minerals to public health and economic development (see Section 3.2).

2.3 Foreign Direct Investment, Trade, and Finance as Indirect Growth Engines

Development assistance, as supplied by U.S. public and private sector actors via grants, loans, equity, and technical assistance, are important sources of financing to support development in low- and middle-income countries. Nevertheless, these flows are smaller and less sustainable than other economic relations between the U.S. and the Global South. For this reason, we must consider the roles of FDI, trade, and financial services as increasingly important parts of the economic growth equation in poorer countries. The opportunity is there for the U.S. to employ these potentially powerful instruments within America’s foreign policy toolkit in ways that are mutually reinforcing with development assistance.

2.3.1 Foreign Direct Investment

Low- and middle-income countries attract a growing share of global FDI outflows. In the last three decades, FDI to developing countries skyrocketed from US$33.6 billion in 1990 to US$916.42 billion by 2022 (UNCTAD, 2023). There has also been a corresponding uptick in FDI targeted to the subset of least developed countries, albeit at more modest levels (from US$542 million to US$22 billion) (ibid). The U.S. was the single largest supplier of outbound FDI in 2022, accounting for US$6.6 trillion globally (BEA, 2023). Nevertheless, the lion’s share of American FDI has focused on advanced economies in Europe and Canada,[5] and Asia and Latin America to a lesser extent (ibid).

Comparatively, emerging markets receive marginal amounts of U.S. FDI, even in contexts with relative political and economic stability (ibid). This status quo is a missed opportunity for developing countries where leaders routinely cite job creation as a top priority (Custer et al., 2022) and for American companies searching for next-generation markets. Africa is a case in point. The continent consistently captured less than 1 percent of American FDI from 2009 to today (U.S. BEA, 2023), despite the tripling of its middle class over three decades (AfDB, 2011) and the future productive potential of the world’s most youthful population (Signé, 2022; PRB, 2023).

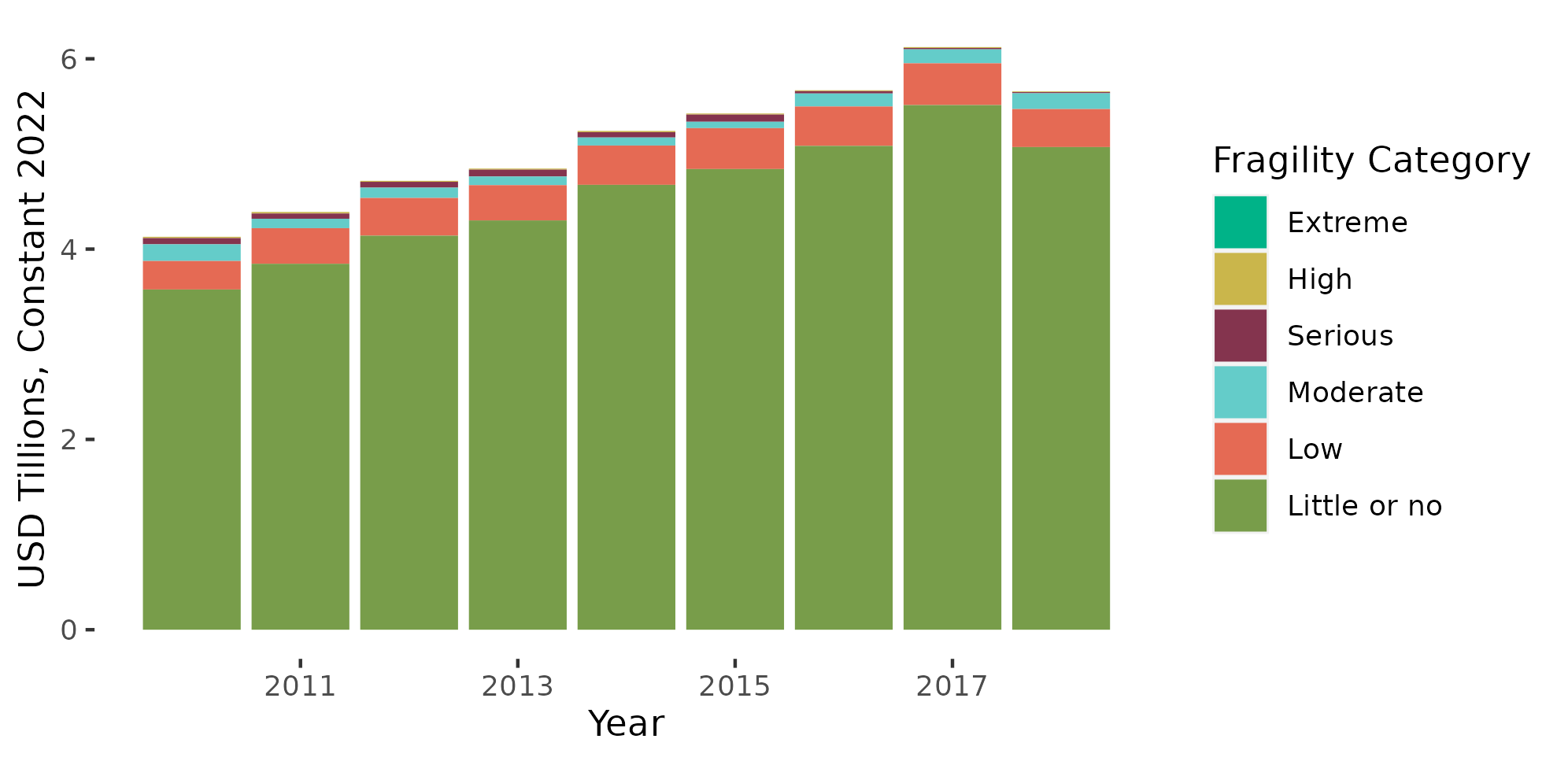

The relative absence of U.S. FDI is more pronounced in countries experiencing higher levels of state fragility. Between 2010-2018, only 2 percent of American FDI was in countries with moderate or worse levels of fragility (Figure 3). Even as U.S. companies increasingly embrace corporate social responsibility programs (G&A, 2020) and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) safeguards (Deloitte, 2022), they are still responsible for delivering profit to their shareholders. By definition, fragile states have less predictable business climates and higher levels of political risk, often making them less attractive destinations for U.S. FDI.

Figure 3. U.S. Outward Foreign Direct Investment Stock, by Country Fragility Level, 2010-2018

Note: U.S. direct investment abroad calculates the value of all investments where U.S. investors own at least 10 percent of a foreign business, including transactions between affiliates and their owners, the income that the investors earn on their direct investments, and the cumulative value – or position – of outward direct investment.

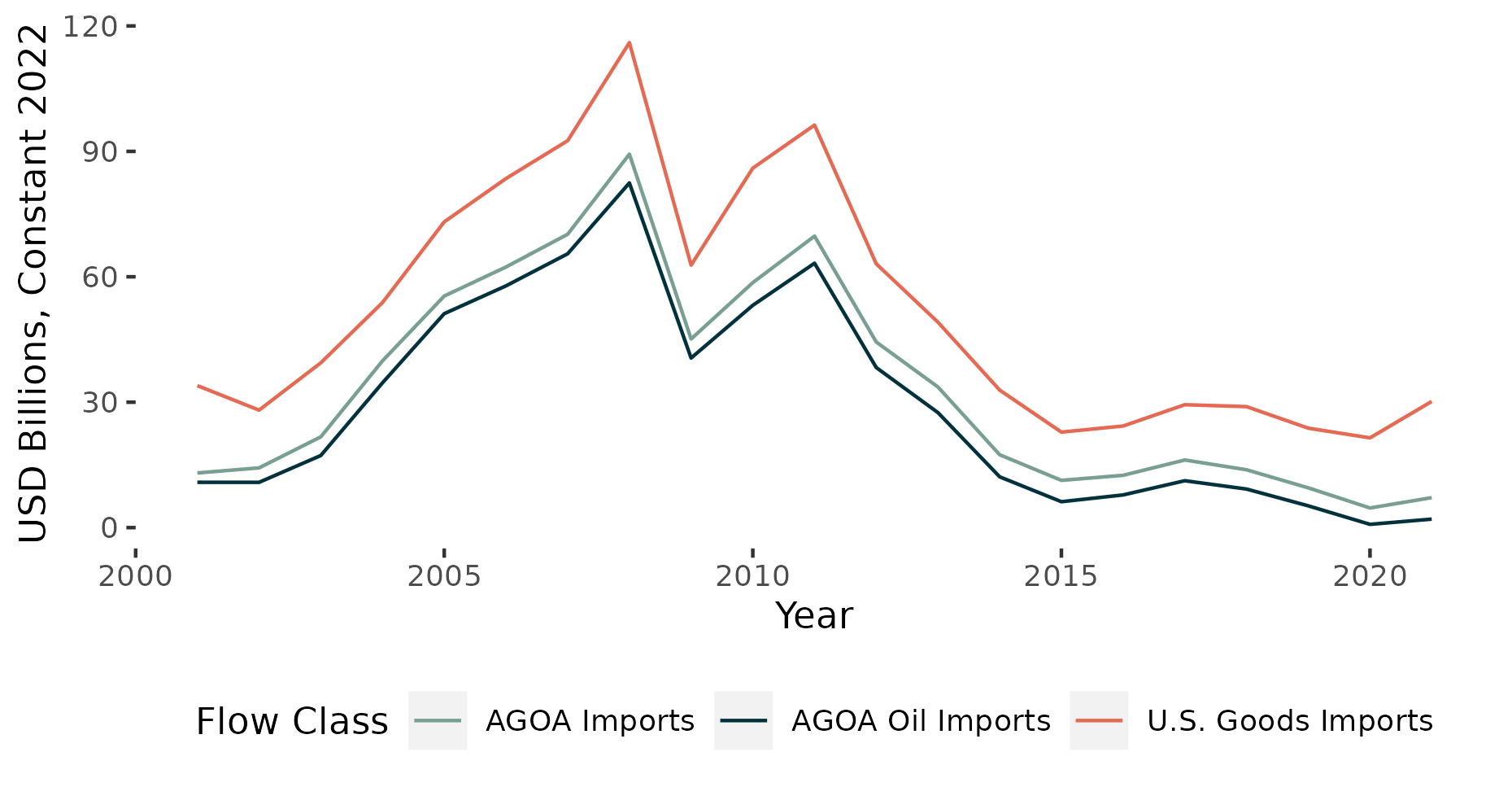

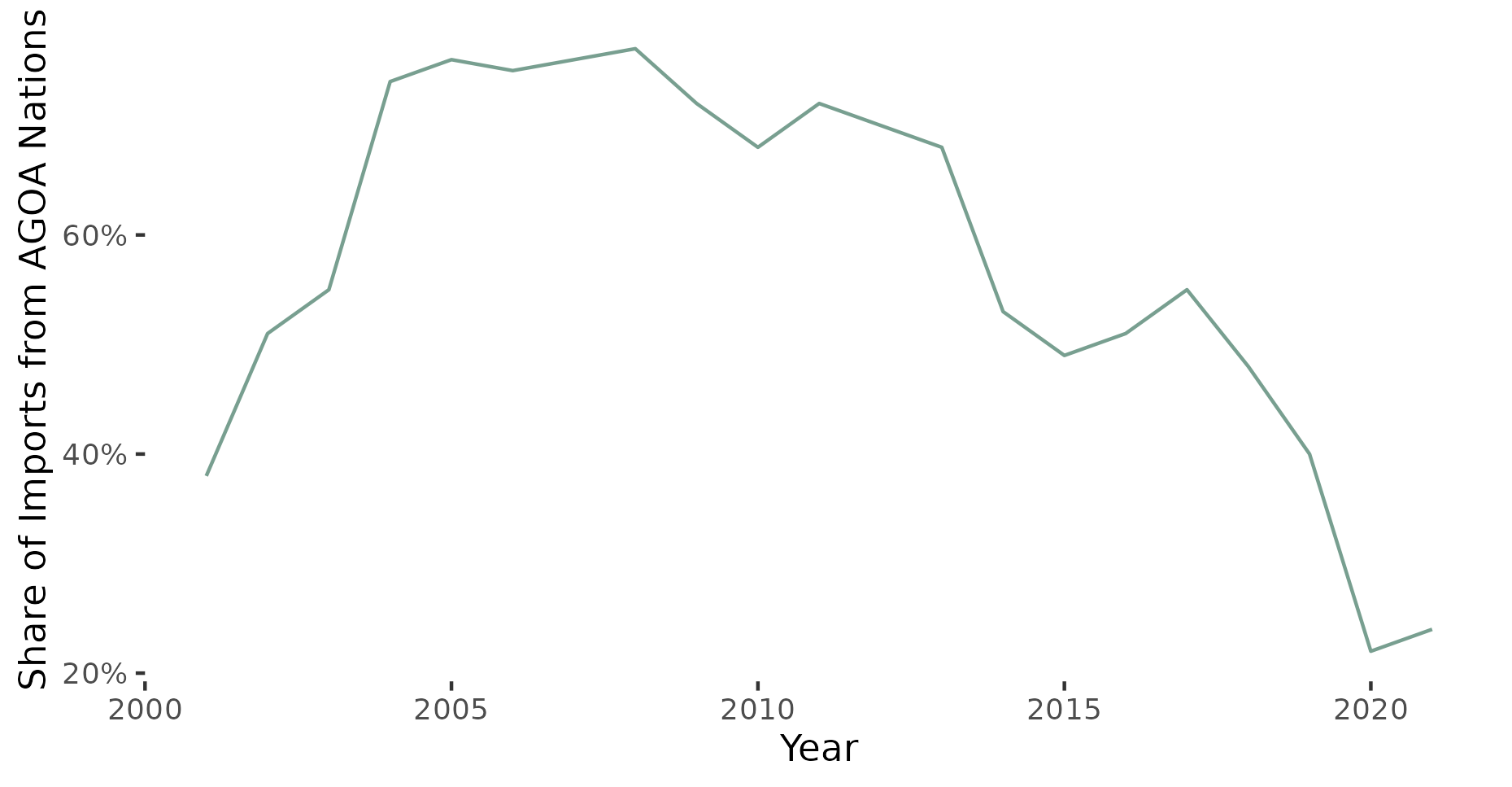

2.3.2 Trade

Trade is another powerful resource to fuel economic growth in low- and middle-income countries. Similar to trends in FDI, trade with developing countries has expanded dramatically from US$4.1 trillion in 2005 to US$13 trillion by 2022 (UNCTAD, n.d.). Although the least developed countries are farther behind in absolute terms, they have seen an uptick in trade that grew 3.6 times during the same period (US$89 billion to US$317 billion) (ibid). However, for trade to catalyze shared prosperity, countries must be more than mere importers of goods and services from advanced economies; they need access to export markets abroad.

Developing countries have broken through to capture an expanding share of the world export market (42 percent in 2022). Their Achilles heel is heavy reliance on a narrow set of commodities and lower-value manufacturing goods—a challenge that is particularly acute in Africa (ibid). By contrast, the least developed countries have failed to launch, remaining stagnant at 1 percent of world exports over two decades.

The U.S. is the world’s second-largest trading nation behind the People’s Republic of China (PRC), accounting for US$7 trillion in exports and imports with over 200 countries in 2022 (USTR, 2023). In the eyes of the Global South, the U.S. is among the top destinations for their exports: 17 percent for developing economies and 8 percent for least developed countries (UNCTAD, n.d.). Nevertheless, these countries make barely a dent within the big picture of U.S. trading relations. Of the US$3.3 trillion in goods Americans imported in 2022, 52 percent came from just five countries: the PRC, Mexico, Canada, Japan, and Germany (USAFacts, 2023).

America’s largest trading partners tend to receive no USG assistance (e.g., Canada, Japan, and Germany) or minimal amounts (e.g., the PRC). The largest aid recipients are heavily skewed toward conflict, post-conflict, and disaster settings. Iraq, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, and Ukraine attracted a quarter of economic aid over the past two decades, none of which had a market capable of sustained engagement with American trade. However, two unique case studies stand out, Mexico and Egypt, that are worth a closer look.

Mexico’s status as a major source of U.S. imports (3rd largest) and destination for U.S. exports (2nd largest) benefits from geographic proximity, favorable trading agreements,[6] and U.S. interest in near-shoring to secure supply chains (Meltzer et al., 2023). It also attracted US$4.2 billion in economic activities over the last two decades, focused on narcotics control, law enforcement, and human rights activities. The 2022-2023 U.S.-Mexico High-Level Dialogue identified the two countries’ shared interests in sustainable economic and social development and cybersecurity (USTR, 2023).

Egypt is a less rosy story: it received ample public sector development assistance in the “trade and investment sector” (US$2.5 billion between 2001-22) but minimal U.S. private sector-led trade. The Middle East and North African region’s populous nation ranks 51st in imports to the US and 33rd as a market for US exports, just behind Vietnam. Its trading levels with the U.S. have been volatile rather than sustained. Two decades of aid for trade assistance, initially as budget support and project finance routed through the government before a pivot to trade promotion activities managed by U.S. private contractors, has not appeared to bear much fruit. Of course, there were numerous complicating factors that likely also affected Egypt’s economy during this period—from political instability (e.g., revolution, elections, a coup d’etat) to macroeconomic instability (e.g., free-floating the pound) (Feteha et al., 2016).

2.3.3 Financial Services and the Role of Commercial Project Finance

The financial services sector contributed 8 percent of U.S. gross domestic product in January 2023 (Trading Economics, 2023). America’s commercial banks and insurance institutions are a comparative advantage and a competitive asset, representing 41 percent of global equity and 40 percent of fixed-income markets (SIFMA, 2021). Although bilateral and multilateral development finance institutions are important sources of capital for the Global South, U.S. commercial financial institutions are underutilized in how America engages with low- and middle-income countries.

Commercial banks have often been a partner of choice for foreign governments and private actors when raising capital to finance private or public sector development projects. However, the landscape of private project finance to support development projects overseas has shifted: there is a growing number of players, the space is dominated by a handful of banks, and American financial institutions have fallen behind their peers (Garcia-Kilroy & Rudolph, 2017).

In 1997, U.S. banks held 50 percent of the private project finance market (ibid). By 2015, this share had declined to 4 percent as U.S. investors navigated recessions (ibid). In parallel, European banks held steady, Japanese banks surged to acquire a quarter of the market (ibid.), and the PRC has flooded the project finance space with commercial finance with the launch of BRI (Malik et al., 2021). In contrast to American or Japanese lending, PRC finance extensively uses co-financing across state-owned policy banks and commercial banks, with nearly a third of Beijing’s loans employing this “hybrid” financing mechanism (ibid).

3. Strategies and Modalities: How Has the U.S. Government Engaged American Private Sector Finance and Expertise to Amplify Development Assistance?

Mobilizing private sector resources to work in low- and middle-income countries, collaborate effectively with public sector agencies, and advance U.S. foreign policy goals is easier said than done (Table 4). Private sector actors are sometimes reluctant because of unknown political, financial, or reputational risks. Philanthropies and non-profit organizations often have a humanitarian mission. In contrast, companies have a responsibility to generate profit for their shareholders, which is difficult to guarantee in contexts with higher instability. Private sector actors may be at a loss regarding whom and how to work in a developing country due to a lack of information, networks, or skills. Meanwhile, partnering with the USG may not hold appeal for various reasons: bureaucratic red tape, cultural divides, philosophical differences, or lack of clarity about the practical value of such collaborations.

Table 4. Private Sector Engagement Pain Points, Engagement Strategies, and Modalities

|

Pain Point(s) to Overcome |

Private Sector Engagement Strategies |

Illustrative U.S. Government Modalities |

|

Political, financial or reputational risks in the developing country |

Hedge against risks of working in the developing country |

Political risk insurance, credit guarantees, currency swaps, investment guarantees |

|

Bureaucratic red tape,organizational or cultural differences working with the USG |

Reduce known downsides of collaborating or partnering with the USG |

USG-focused acquisition and procurement reforms, building capacity and culture of private sector engagement |

|

Unclear benefits of engaging (e.g., market potential, reputational benefits) |

Increase likely upsides of working in the developing country |

Country-focused reforms to improve business and investment climate, joint promotional activities with the USG and partner country government, tax incentives, reduced trade barriers |

|

Unclear value of collaborating or partnering with the USG |

Improve the known benefits of collaborating or partnering with the USG |

Equity investments, investment funds, debt financing, matching contributions, PPPs, export promotion |

|

Uncertainty about who to engage with and how due to lack of information, networks, or skills |

Alleviate uncertainties of working in the developing country |

Feasibility studies, technical assistance, deal teams, matchmaking to twin U.S. companies with local counterparts, capacity building |

3.1 Hedging Risk, Alleviating Uncertainties of Working in Developing Countries

Lack of access to affordable long-term financing is a critical constraint to growth. Without it, low- and middle-income countries cannot invest in activities that generate lasting economic value and societal benefits (Spiegel & Schwank, 2022). Countries may have more options to finance their development than ever (Greenhill et al., 2013), but at a steep financial cost, often three times higher than advanced economies (Spiegel & Schwank, 2022). Perceived risks from political instability or lack of local market knowledge make private sector investment more unpredictable, reflected in higher capital costs (ibid).

Meanwhile, domestic government revenues and international grant-based assistance are too small-scale to substitute for a ready supply of FDI to support growth sustainably (World Bank, 2017). Bilateral development assistance providers like the U.S. and multilateral development banks have long sought ways to incentivize private sector investment that is mutually beneficial for advanced and emerging economies alike (Gordon, 2008).

3.1.1 The Antecedents of the Development Finance Corporation

America’s first foray in this vein was the formation of two U.S. Export-Import Banks in 1934 by President Franklin Roosevelt. The banks focused on stimulating trade with the Soviet Union and the rest of the world before being merged by Congress in 1935 (State, n.d.d). The Export-Import Bank Act of 1945 would make the Export-Import Bank a U.S. government corporation (Bryant, 2003). The motivation was two-fold: kick-start the economy, promote American exports abroad following the Great Depression and rebuild Europe after World War II (ibid). From then until now, the Export-Import Bank has helped U.S. firms cultivate overseas markets for their products via direct loans, loan guarantees, and export credit insurance, which helps to offset potential losses in risky markets in the event of political instability or default (White House, 2015; Bryant, 2003).

The USG’s embrace of political risk insurance was not limited to export promotion. Dating back to the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (P.L. 87-195), Congress granted a three-year authorization for the Kennedy administration to issue investment guarantees[7] to promote private sector investment in low- and middle-income countries (Akhtar, 2016). In 1969, it passed legislation to formally establish the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) with a mandate to help companies manage risk associated with FDI and gain footholds in new markets. OPIC entered into operation in 1971 as a wholly-owned USG corporation (Akhtar, 2016). President Richard Nixon stressed that the new agency “cannot substitute for government assistance programs,” instead that two channels can reinforce one another (ibid).

OPIC served as the lead USG development finance institution through the rest of the Cold War, the 1990s, and the 21st Century. It offered loans, guarantees, political risk insurance, and support for investment funds to help U.S. businesses contribute to economic growth in emerging markets (OIG, n.d.). One success worth highlighting for OPIC was its ability to promote private sector investment in some of the most challenging business climates in the world: fragile states. As a case in point, over a quarter of all OPIC commitments went to fragile countries. This includes US$1.5 billion (nearly 4 percent of commitments) in “high” fragility contexts to support financial sector development and electric projects in Burkina Faso, Uganda, and Pakistan.

OPIC, of course, was a bilateral extension of what multilateral development banks like the World Bank had piloted earlier with the launch of its International Finance Corporation in 1956, which encouraged private investment through a blend of co-financing, identification of promising opportunities, and advisory services (IFC, 2016; World Bank, n.d.). OPIC would not only model itself after the International Finance Corporation but also the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Authority established by the World Bank Group in 1988 as a “multilateral provider of political risk insurance” with the U.S. as one of 29 original members of the “legally separate and financially independent” entity (MIGA, n.d.). The differentiator between these multilateral channels and OPIC was the latter’s animating focus on catalyzing involvement of the U.S. private sector in emerging markets as opposed to companies from other countries.

Mainline development agencies like USAID also embraced insurance guarantees by forming the Development Credit Authority under the Office of Development Credit in 1999. The Development Credit Authority offered four types of insurance guarantees to make it less risky for banks and other financial institutions to offer access to cheaper lending for micro, small, and medium enterprises in emerging markets to scale their businesses (Wasieleweski, 2017; OECD, 2016). It stood apart from other instruments available to USAID as the Development Credit Authority set out from the start to be “private sector driven” but “development focused”: it encouraged lenders to supply credit in alignment with their existing business standards and processes, shared the risk to make it easier to lend to less well-known borrowers in ways that would advance development outcomes, and positioned USG funding as leverage to crowd-in larger scale private capital (ibid).

Over 17 years (1999-2015), the Development Credit Authority worked with 480 financial partners to supply US$4.2 billion in private capital to 215,000 borrowers in 74 countries at a default rate of 2 percent (OECD, 2016a). USAID also appeared to successfully use the Development Credit Authority funding mechanism to mobilize US$35.6 million in PPP finance for extremely fragile contexts. These USAID projects supported the financial sector and banking in Ethiopia, solar plants in Burundi, and four separate projects in Afghanistan in 2017 and 2018.[8]

The purpose and form of the Development Credit Authority’s financial offerings differed substantially from OPIC in several ways. OPIC worked with U.S. private companies, providing 100 percent guarantees on debt financing in the event of loss (Wasielewski, 2017). The Development Credit Authority offered 50 percent guarantees to non-U.S. and U.S. institutions (ibid.). OPIC was an independent, free-standing entity. The Development Credit Authority was a specialized tool within USAID’s larger toolkit to be used alongside grants or technical assistance. Combining these tools reduced the likelihood of borrower default in the short-term and improved their long-term creditworthiness (ibid).

3.1.2 The Arrival of the BUILD Act and the Development Finance Corporation

This status quo changed with the arrival of the U.S. International Development Finance (DFC). In 2018, Congress passed the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act to consolidate two streams of guarantee and development-loan authority, OPIC and USAID’s Development Credit Authority, under one roof. Established in 2019, the DFC is a one-stop shop for a more expansive set of financial products, offering direct loans and guarantees, equity investment, investment funds, feasibility studies, political risk insurance, and technical assistance in project planning (DFC, n.d.c). The legislation marked an expansion of U.S. development finance potential: it doubled the amount of money DFC could invest to US$60 billion from US$29 billion under the OPIC era.

Because its revenues are appropriated by Congress using U.S. Treasury lending, the DFC does not need to maintain a credit rating, reducing the burden of investing in riskier markets. It returns the proceeds of its loans to the Treasury, which it did to the tune of US$394 million in the first two full years of its operation in FY2020 and FY2021 (Akhtar & Brown, 2022). Beyond the two traditional motivations for U.S. development finance—promote American commercial interests abroad and reduce costs for emerging markets to access financing for development —there was a third animating factor in DFC’s creation: geostrategic competition with the PRC and its Belt and Road Initiative.

The legislation did not explicitly refer to the PRC by name. However, it says that the DFC’s goal is to “facilitate market-based” growth in less developed countries and “provide a robust alternative to state-directed investments by authoritarian governments and strategic competitors” (BUILD Act §1411, 2018; Akhtar & Lawson, 2019). The move was widely understood by Democrats and Republicans as inspired, at least in part, by increasingly heated competition between the U.S. and the PRC to project influence in the Global South (Thrush, 2018; Akhtar & Lawson, 2019), a topic central to the last two national security strategies in 2017 and 2022 (White House, 2017 and 2022c).

The new agency started slowly, with the first few deals only materializing in 2020. Structurally, its ability to source new projects was limited without a presence on the ground in partner countries. Large-scale investments take time to operationalize, particularly while adhering to Congressionally-mandated social and environmental safeguards. The DFC has a larger resource pool to work with than its predecessors but operates within an investment cap (US$60 billion) that pales in comparison to the US$85 billion per year (or higher) in total development finance the PRC committed on average in the first five years of BRI implementation (Malik et al., 2021).[9]

In background interviews conducted for this research, some observers argued that the DFC was too risk intolerant, deterring it from investing in riskier sectors and markets. The U.S. Treasury arguably imposes some of these constraints over concerns about risk to U.S. markets, and congressional and executive branch leaders request waivers for the DFC to fund priorities in upper-middle or high-income countries.[10]

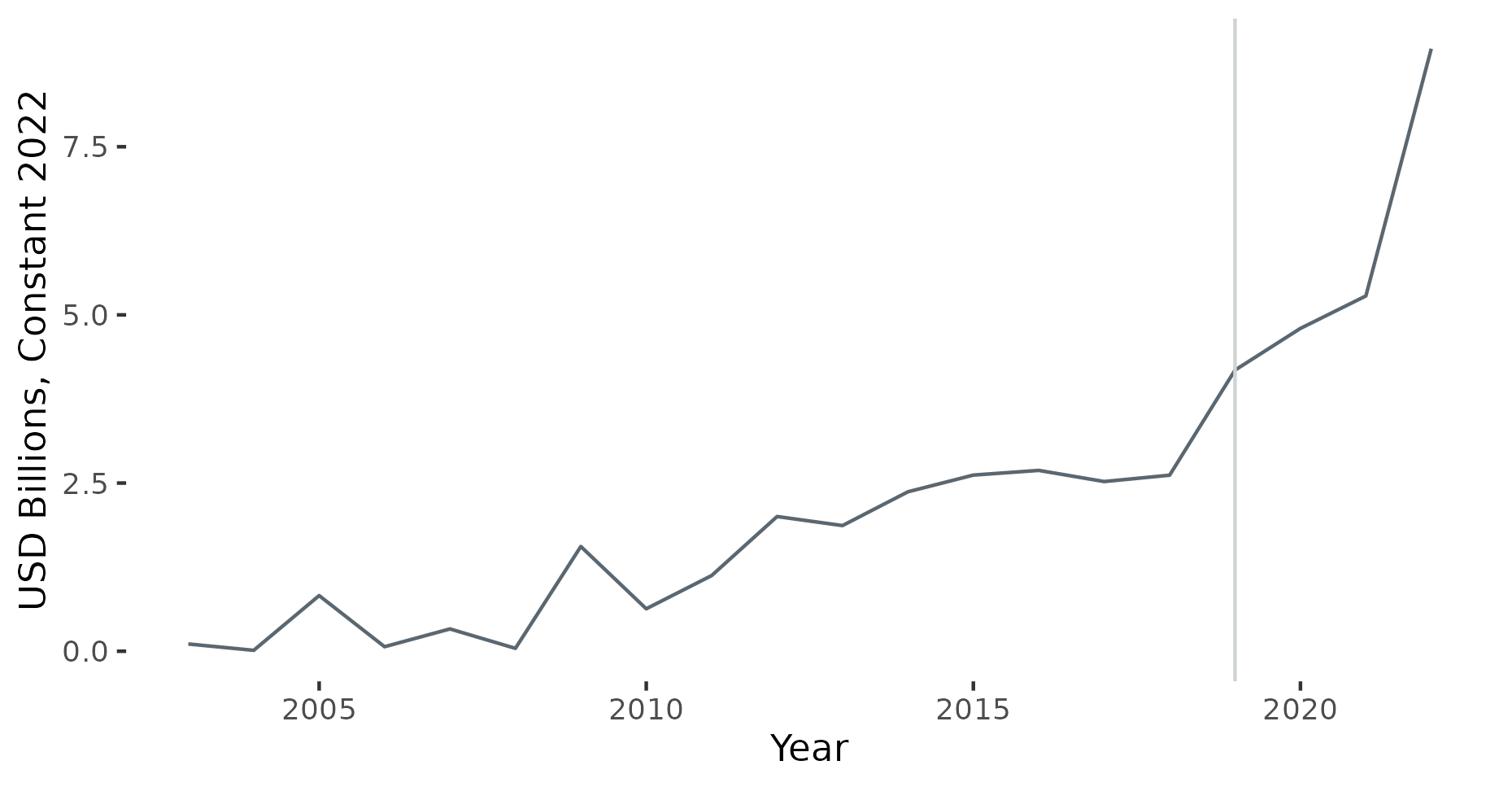

Nevertheless, there has indeed been an uptick in new financing committed even in the first few years under the DFC name. In just three years (FY20-22), the DFC committed US$18.1 billion to support overseas development, compared with OPIC’s US$28.5 billion over 21 years (DFC, n.d.i). DFC also set a new record in fiscal year 2022 with commitments of US$7.4 billion across 183 transactions and exposure in 110 countries (DFC, 2022b). The DFC has thus far maintained a slim majority of its portfolio in low-, lower-middle, and fragile countries. However, transaction-level data (FY20-22) confirms extensive use of waivers—from investments in three high-income contexts (regional connectivity in Eastern Europe, fiber-optic cables in Singapore, and a hospital in Oman) to 24 upper-middle income countries and several regionally focused efforts tagged as benefiting upper-middle or high-income countries.[11]

Figure 4. Value of New Investment Support Project Commitments by OPIC and DFC, 2000-2021

Note: The vertical gray line indicates the establishment of DFC and its adoption of OPIC projects. OPIC and DFC commitments only represent the original principal/investment value that DFC has committed to provide or guarantee, by fiscal year, that projects were first obligated. For Insurance transactions, the original aggregate coverage limit that DFC has committed to provide. It does not reflect repayments or capitalized interest or capture the private sector resources invested in projects. Source: Development Finance Corporation.

In some respects, the DFC’s investments reflect a continuity from the priorities of the OPIC era. Although the DFC has five stated sector priorities,[12] in practice, it has directed nearly half of its investments for fiscal years 2020-2022 to finance and insurance activities related to micro, small, and medium enterprise (MSME) banking institutions or initiatives targeting women’s financial inclusion—consistent with its predecessor OPIC. Both OPIC and DFC also committed substantial funds to utilities.

However, the geostrategic context within which the BUILD Act was passed (i.e., competition with the PRC’s BRI) is evident in the DFC’s early funding priority to underwrite projects related to oil, gas, and mining. In just a few years, the DFC’s commitments in the extractives industry (US$1.7 billion) exceeded the entirety of OPIC’s support to the sector over the previous 17 years (US$1.5 billion). The DFC’s commitments are largely driven by political risk insurance supplied to an LNG project in Mozambique and a non-Russian gas development project in Moldova. Despite the Biden administration’s stated climate commitments and the DFC’s support for a first round of green bonds in Egypt, supporting new energy production projects is of growing political interest to help countries reduce dependence on Russian LNG imports.

Relatively high levels of investment in the extractives sector appear to have displaced other DFC-stated priorities, such as agriculture. The second highest priority for USAID’s Development Credit Authority, agriculture projects only account for 0.6 percent of DFC financing commitments thus far (US$9.4 million). Despite being a named priority for DFC, healthcare has been less prominent in early investments than expected, especially as countries seek to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic and strengthen their internal systems to prepare for the next one.

One noteworthy exception is the DFC’s recent partnership with Aspen Pharmacare. Based in South Africa, the company received the Gates Foundation and Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations grants to strengthen the production of vaccines in Africa. This set the stage for the DFC to provide scale-up financing that enabled Aspen to extend production capacity to up to 450 million vaccine doses per year, addressing a range of diseases (DFC, 2023).

The geographic profile of investments has also shifted somewhat between the OPIC and DFC eras. Three regions come out ahead, attracting a growing share of new investments between the OPIC and DFC periods, including Latin America and the Caribbean (from 29 to 36 percent), Sub-Saharan Africa (22 to 32 percent), and South and Central Asia (9 to 17 percent). Within South Asia, India is a major investment destination, accounting for US$870 million in commitments across 14 projects from manufacturing and MSME finance to microlending in fiscal year 2022. Comparatively, Europe and Eurasia (from 12 to 2 percent) and the Middle East and North Africa (from 17 to 3 percent) have become less of a priority for DFC than OPIC.

Figure 5. Value of New Investment Support Project Commitments by DFC and OPIC, by Region, 2000-2021

Note: The vertical gray line indicates the establishment of DFC. This figure excludes commitments with worldwide intent. OPIC and DFC commitments only represent the original principal/investment value that DFC has committed to provide or guarantee, by fiscal year, that projects were first obligated. For Insurance transactions, the original aggregate coverage limit that DFC has committed to provide. It does not reflect repayments or capitalized interest or capture the private sector resources invested in projects. Source: Development Finance Corporation.

In its second year of operation, DFC leadership pursued opportunities to coordinate and collaborate with mainline development agencies. It launched and led the Development Finance Coordination Group (DFC, 2022a), which marked an early success in facilitating a new small business initiative with the U.S. African Development Foundation to grant loans to early-stage companies (ibid.). Outside of Washington, the DFC’s Mission Transaction unit works within USAID missions to identify access to finance challenges in developing countries and encourage banks to lend to priority development projects (DFC, n.d.a). Early wins include the launch of loan portfolio guarantees with four commercial banks in Serbia to improve access to finance for small and medium enterprises (DFC, 2022d). The DFC CEO, as Executive Chairman of Prosper Africa, also ensured that the DFC has a core role in the government-wide initiative and facilitated the rapid expansion of DFC projects on the continent (Figure 5) (DFC, 2022a).

3.2 Reducing Downsides, Improving Upsides for the Private Sector to Engage with the USG

The USG has a long history of contracting private sector entities to implement development assistance programs (since the 1960s) and supplying loans and loan guarantees via OPIC (since the 1970s). However, it has a shorter track record of mainline development agencies brokering private sector partnerships that pool financing, risk, and expertise (Lawson, 2013). Indeed, many of the modern contracting partnerships emerged in part as a means of mitigating risk in project delivery between the USG and partners, yet few vehicles that view risk as a potential tool are newer on the scene.

3.2.1 USG Stated Priorities and Approaches to Private Sector Engagement

President George W. Bush’s Global Development Alliance program, launched in 2001, was USAID’s first formal mechanism to co-create projects with the private sector to advance business and development objectives (USAID, n.d.c). The initiative included resource partners that contribute funding or in-kind contributions to match USG funding at a ratio of one-to-one or greater, as well as implementing partners that execute the delivery of projects (OECD, 2016). This mechanism had staying power, only retired in August 2023, and transitioned to the Private Sector Collaboration Pathway (USAID, 2023b).

Since 2004, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) has engaged the private sector in three ways: soliciting advice on constraints to growth via Advisory Councils at global and country levels, crowding in private sector capital to invest alongside its grant-based funding, and providing open procurement opportunities (Lee, 2022; MCC, n.d.e). Bush’s Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, brought private sector partnerships to the Department of State, establishing a Global Partnership Center in the Bureau for Research Management in 2008 to tap into private sector expertise and resources to strengthen diplomacy and development outcomes (Lawson, 2013). The Center’s objective was to mobilize US$150 in private sector commitments for every US$1 in USG funding spent as a convener of people around shared interests and catalyst of projects benefiting from market solutions (State, 2009-2017 Archive). An early Bush-era PPP initiated in 2002 featured collaboration between USAID, the United Nations Development Program, and ChevronTexaco focused on the agriculture and water sectors in Angola.[13]

President Barack Obama doubled down on his predecessor’s private sector partnership efforts and made them his own. He renamed the Global Partnership Center to become the Global Partnership Initiative. He elevated its status to that of a seventh-floor entity reporting directly to the Office of the Secretary of State (Lawson, 2013). The Office remains today and has worked with over 1600 partners to mobilize US$3.7 billion in combined public and private sector resource commitments (State, n.d.e). Obama institutionalized the Global Development Alliance mechanism, along with a broader emphasis on private sector partnerships, as a core pillar within USAID's new Global Development Lab (Lawson, 2019; USAID, 2017-2020 Archive).

Mobilizing private sector involvement was prominent in Obama’s 2010 Presidential Policy Directive on Global Development (White House, 2010). He sought to integrate private sector perspectives, from policy conception to program implementation, to multiply the impact of USG development assistance. The U.S. Global Development Council was formed to solicit input from “the philanthropic sector, private sector, academia, and civil society” (White House, 2010), as well as overcome barriers to collaboration in order to “support new and existing public-private partnerships” (White House, 2012).

The administration piloted new initiatives to crowd in private sector engagement. The MCC’s Public-Private Partnership Platform was launched in 2015 with a budget of US$70 million to catalyze private sector financing worth US$1 billion over five years (OECD, 2016j). These projects were to be “country-led” and meet the agency’s required criteria (e.g., country scorecard performance, project cost-benefit analysis, and due diligence processes)(ibid). State’s Office of Global Partnerships introduced smaller-scale efforts to engage diaspora communities (e.g., Diaspora Voices, International Diaspora Engagement Alliance), educational institutions (e.g., Diplomacy Lab), and private companies (e.g., an Impact Award to celebrate leading Public Private Partnerships, the Global Entrepreneurship Program) (State, n.d.e; State, n.d.f).

However, Obama’s emphasis on sector-based PPPs is arguably one of the most visible examples from this era and has longer staying power. Power Africa was launched in 2013, with support from 13 USG agencies and 200 private-sector partners, to boost energy capacity across African countries (USAID, 2023a). The initiative doubled the USG commitment with de-risked private sector funds in its first year (Congress, 2014). The DREAMS partnership against HIV/AIDS launched in 2014 with the Gates Foundation, Girl Effect, Gilead Sciences, Johnson and Johnson, and ViiV is one of many examples in the global health arena (State, n.d.h; OECD, 2016e). The Responsible Minerals Trade Alliance mobilized private sector actors in telecommunications (e.g., AT&T, Verizon, Nokia) and Silicon Valley (e.g., Dell, Hewlett Packard, Intel) from 2010-2012 to support transparent sourcing of conflict-free minerals such as tin, tungsten, and gold (OECD, 2016i).

President Donald Trump continued the Obama era emphasis on private sector engagement, retaining earlier instruments such as USAID’s Global Development Alliances and the State’s Office of Global Partnerships. It also embarked on its own initiatives, one of which was Boldline, an accelerator launched in 2018 to scale up successful early-stage partnerships and provide additional connection points between the public and private spheres (State, n.d.a). USAID Administrator Mark Green’s Private Sector Engagement Policy placed a premium on “enterprise-driven development” and “market-oriented solutions” as part of the agency's “Journey to Self-Reliance” strategy (USAID, 2018a). The policy sought to incentivize private sector engagement across the agency with four principles: engage private sector counterparts early and often, incentivize and value private sector engagement in planning and programming, expand the use of approaches and tools to unlock private sector potential, and build and act on the evidence of what works and does not (ibid).

Blended finance, the strategic deployment of public sector funds to improve an investment’s “risk-adjusted return,” gained substantial attention in the Trump era (USAID, 2020).[14] The American Catalyst Facility for Development paired the MCC’s grant-based mechanisms with the DFC’s debt financing in support of “coordinated, strategic investments” (MCC, n.d.a), syncing up the two agencies’ investment cycles and business models that had previously hindered deep collaboration (DFC, 2022b). A joint MCC-DFC task force met in 2020 to lay the groundwork to operationalize the new blended finance facility (ibid). However, the first three compacts featuring these funds would not be signed until 2022 under the Biden administration with the governments of Lesotho, Kosovo, and Malawi (MCC, 2022).

In a second initiative, MCC launched the Millennium Impact Infrastructure Accelerator in October 2020 with Africa50, an investment platform established by African governments and the African Development Bank to mobilize private sector capital in critical sectors (e.g., power, water, sanitation, health, education, transport) (ibid). The accelerator sought to “address the root challenges to project development in emerging markets” by building a pipeline of “bankable, high-impact projects” and matching them with sources of public and private finance (MCC, 2023b). As of 2022, MCC reported that the initiative had a pipeline of 8 projects in varying stages of pre-feasibility assessment (MCC, 2022).

In parallel, USAID unveiled two of its own blended finance initiatives. USAID INVEST sought to help private sector partners overcome barriers to identify and buy-in to commercially viable projects in emerging markets (USAID, 2023g). It offered four services—identification of investment opportunities; transaction advisory services to link suppliers with capital seekers; structuring of blended finance instruments that feature grant, debt, and equity; and technical assistance to help with project pre- and post-feasibility assessments (ibid). In its sixth year of operation, USAID INVEST has cultivated a network of 579 private sector firms, facilitated 66 buy-ins, and mobilized US$1 billion in private capital for commercially viable projects in 82 countries (ibid). The focus of these projects is varied but dominated by investments in the financial and energy sectors (ibid).

USAID CATALYZE sought to complement INVEST with an emphasis on creating an enabling environment for sustainable private sector investment and capital beyond the life of any one project, supporting market assessments and other activities to incubate new deals (USAID, n.d.b). The first eight activities under CATALYZE began in 2019-2020 with US$86 million to support projects in education, financial services, women’s empowerment, agriculture, workforce development, and private sector development (ibid).

President Biden argued that the USG should work to increase “the efficiency and efficacy” of its engagement with the private sector in his Memorandum on Revitalizing America’s Foreign Policy and National Security Workforce, Institutions, and Partnerships (White House, 2021). In response to the memo, USAID Administrator Samantha Power launched the Private Sector Engagement Modernize initiative in 2022, building upon her predecessor’s 2018 policy by outlining a series of reform initiatives to address a critical lack of agency skills and capacity to engage the private sector (USAID, 2023c), including closer collaboration with DFC (Ingram & Reichle, 2023). A new Private Sector Collaboration Pathway (the old Global Development Alliances by another name) emphasizes pursuing shared interests, joint responsibility, and co-creation (USAID, 2022b; USAID, n.d.d.).

Biden carried forward the interest in blended finance, focusing these efforts around realizing the administration’s ambitious 2022 commitment that the U.S. would mobilize US$200 billion over five years for the Partnership for Global Infrastructure (White House, 2022b). In announcing a series of flagship initiatives, Biden wanted to demonstrate how public sector investments could catalyze hundreds of millions or even billions of private sector capital to advance development, diplomatic, and commercial goals (ibid). As of May 2023, the initiative had mobilized US$30 billion via grants, federal financing, and leveraging private sector funds (White House, 2022b).

A new USAID Digital Invest program was a case in point: it would leverage a small amount of USAID and State funding (US$3.45 million) to crowd in much larger private sector capital up to US$335 million to advance competition and choice of Internet service providers and financial technology companies in emerging markets (ibid).[15]The Biden administration’s flagship initiative in this area, the Enterprises for Development, Growth, and Empowerment fund, aims to mobilize $50 million for sustained PPPs in areas related to the climate crisis, gender equality, and economic growth (USAID, 2023).

3.2.2 USG Revealed Priorities: Two Channels of Support to Public-Private Partnerships

In an environment of imperfect information, we triangulated the few data points available to examine two main channels by which USG funds may have benefited Public Private Partnerships since 2001.[16] U.S. agencies can help scale existing partnerships aligned with U.S. development assistance priorities, such as the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative or Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition. They can also deploy their resources and convening power to incubate fledgling partnerships that leverage USG funds. Although there are powerful examples of the U.S. supplying catalytic financing in support of partnerships in both respects, the level of investment is underwhelming. Examining the historical financing data surfaces several key insights about the USG’s follow-through on deploying its development assistance budget in ways that catalyze private sector capital.

One positive trend is that agencies like USAID appear to derive an increasing amount of leverage (i.e., non-USG dollars mobilized for each USG dollar spent) in the private sector partnerships they support—from 2.4 times public funding to 3.6 times by 2015.[17] The largest leverage in a single effort was the USAID FIRMS Project in Pakistan, which leveraged $17.1 million (current) in government obligations against US$693.9 million (current) to invest in small and medium enterprises in the agriculture and manufacturing sectors (USAID, 2019). Food security also attracted high-leverage partnerships to support water-efficient maize, heat-resistant wheat, and stress-resistant rice production with the Gates Foundation and Arcadia Biosciences, among others (USAID, 2019).[18]

A second positive signal is that USAID’s Global Development Alliance may have helped the agency crowd in additional resources for countries too unstable for purely private sector investment. Thirteen percent of these investments over nearly a decade (2010-18) went to countries categorized as highly or extremely fragile (ForeignAssistance.gov). Comparatively, these contexts attracted just 0.2 percent of American FDI. Beyond the agriculture and environment focus of the Global Development Alliance, the USG invested a substantial share of funding (70 percent) for existing PPPs in global health (ForeignAssistance.gov), largely driven by the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

One of the largest USG investments in a health-focused partnership was support to the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative under four cooperative agreements stretching from 2001 through today. The most recent investment was the 10-year, US$340 million ADVANCE (Accelerate the Development of Vaccines and New Technologies to Combat the AIDS Epidemic) cooperative (IAVI, n.d.a). The initiative is a prime example of how the USG can magnify, if not necessarily leverage, funds through multi-partner PPPs. Founded by the Rockefeller Foundation in 1994, the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative also attracted funding from the UK government (since 1998) and the Gates Foundation (since 1999) (IAVI, n.d.b.). It scaled considerably with USG support (US$655 million over the past two decades).

However, a vulnerability evident in USAID’s private sector partnerships is that they may rely on a relatively small number of repeat implementing partners and donor darlings.[19] This includes US-based organizations such as Chemonics International and Fintrac Global, Development Alternatives Incorporated and Technoserve, and ACDI/VOCA, along with local partners like the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (Kenya),[20] 3 million Emerging Farmers Partnership (Tanzania), and Social Marketing Company (Bangladesh).

PPPs may face another challenge: waning enthusiasm. USAID funding for new partnerships under its flagship Global Development Alliance grew twelvefold between 2011 and 2017 before losing steam in 2018 and 2019, declining further amid COVID-19 and its aftermath to only US$47 million by 2022 (ForeignAssistance.gov). By contrast, total development assistance moved in the opposite direction, growing 34 percent between 2018 and 2022. More broadly, nine USG agencies bankrolled US$1.1 billion in activities with existing PPPs[21] (US$50.1 million/year on average) over 22 years (2001 and 2022). Accounting for only 0.17 percent of USG development assistance dollars, USAID contributed 91 percent of these funds, followed by State (8 percent). USG money channeled to existing private sector partnerships was never substantial but tapered off in recent years across all agencies.[22]

3.3 Improving Business Climates and Market Potential for U.S. Investment and Trade

Although countries in the Global South have become more integrated into international financial markets over the last few decades, U.S. trade and investment lags behind. The USG has historically employed several mechanisms to get the incentives right for mutually beneficial private-sector investment and trade with developing countries. An illustrative, though non-exhaustive list includes: (i) the provision of technical assistance to partner countries to more easily integrate with trading markets (e.g., “aid for trade”); (ii) reducing market access barriers for firms from developing countries to export their goods to the U.S. (e.g., tariff preference programs); (iii) extending agreements with preferential terms that reduce costs or increase competitiveness for U.S. firms to trade with another country and vice versa (e.g., bilateral or regional Free Trade Agreements, FTAs); and (iv) advisory services and support to U.S. firms in finding partners and negotiating deals (e.g., “deal teams”).

3.3.1 Aid for Trade

The USG is the single largest supplier of trade capacity-building technical assistance across 110 countries, according to data from an annual interagency survey conducted by USAID (n.d.e). This aid for trade assistance helps countries gain access to new markets, comply with international free trade standards, improve the investment climate, and build their competitiveness on a global stage. Illustrative activities include advisory support in streamlining customs and procurement procedures, negotiating trade agreements, strengthening access to financing for exports/imports, and removing trade barriers. Projects like the MCC’s US$188 million Benin Access to Markets project in the port of Cotonou have had direct and measurable impacts on costs and processing time, which are crucial in supporting the growth of trade (MCC, n.d.b.; Gero et al., 2016)

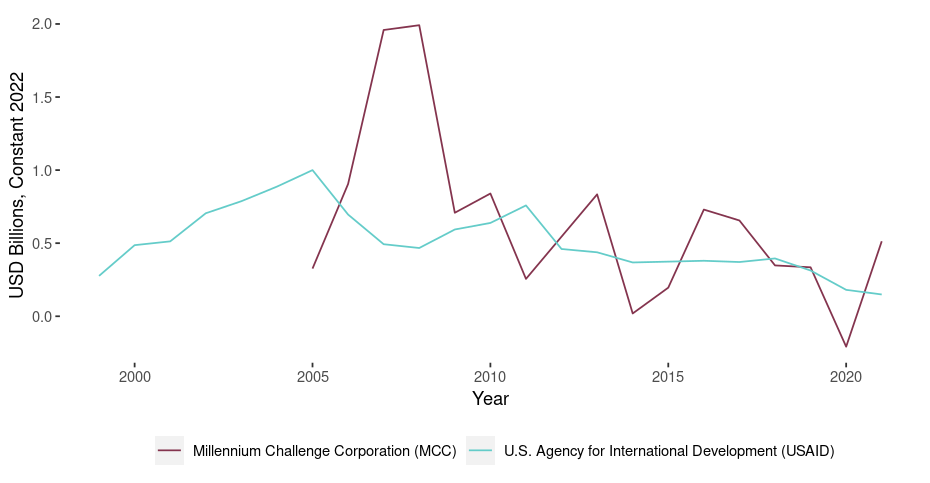

Over two decades (2001-2023), 25 USG agencies obligated US$32.5 billion in trade-based capacity building (USAID, 2023d).[23] Three-quarters of these funds were managed by just three agencies: USAID (36 percent), MCC (32 percent), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (7 percent). USAID supports more but smaller activities (2246 activities, US$5.2 million on average), and MCC bankrolls fewer and larger activities (266 projects, US$39.1 million on average). MCC’s aid for trade assistance is the most volatile across the agencies and accounts for most of the fluctuations in funding for these activities—from a surge in 2007[24] to a drop-off in 2015 and the nadir of 2020 (Figure 6).[25] Unlike much of the USG’s grant-based funding, agencies predominately deploy aid for trade” assistance to middle-income countries (63 percent).

Figure 6. USAID and MCC Obligations to Trade Capacity Building Projects, 1999-2021

Note: This graph captures net obligations with the MCC and USAID as implementing agencies by fiscal year of obligation. Negative values reflect de-obligation of funds. Source: USAID Trade Capacity Building Database, 2023.