U.S. Development Assistance: Evolving Priorities, Practices, and Lessons from the Cold War to the Present Day

Samantha Custer [1]

AidData | Global Research Institute | William & Mary

November, 2023

Gates Forum II Background Research

Executive Summary

This paper retrospectively looks at U.S. development assistance at three junctures: the Cold War, the post-Cold War and 9/11 period, and the contemporary era. It discusses how the Global South perceives the U.S. as a development assistance supplier in a crowded marketplace. It surfaces six takeaways for policymakers to consider in how they can strengthen America’s development assistance in the future.

Pivot from Strategic Ambiguity to Strategic Clarity . America has an overabundance of plans but a dearth of strategic guidance for what U.S. development assistance should achieve and how it evaluates success. Candor about how aid intersects with other foreign policy tools to advance America’s multiple national interests could get the incentives right to reward outcomes, facilitate agency specialization, and support coordination to ensure interagency efforts are more than the sum of their parts.

Move from Operational Incoherence to Operational Complementarity . Development assistance agencies have proliferated—from the Cold War to today. Overlapping mandates, parallel structures, and separate funding create operational incoherence, compounded by competition and lack of coordination. This status quo is a poor use of a meager budget, accounting for less than one percent of federal spending. Partner nations and donors are confused when dealing with a cacophony of interagency voices.

Shift Accountability from Process to Outcomes . Holding agencies accountable for the responsible use of taxpayer money is reasonable. However, runaway procurement and reporting requirements perpetuate an audit culture that rewards compliance and consistency rather than innovation, learning, or ensuring that development assistance dollars generate the outcomes the U.S. and its partner nations want.

Don’t Allow Short-termism to Undercut Long-term Interests . Resources have a way of dictating priorities, and a growing share of the funds for America’s lead development assistance agency (USAID) in recent years has been focused on humanitarian relief. This state of play makes USAID vulnerable to seeing its long-term development mission displaced by short-term imperatives of crises, conflicts, and disasters.

Reposition U.S. Assistance Tools to Be Responsive to Market Demand . There is a mismatch between what America offers and what its partners want. Few assistance dollars are channeled to build the capacity of local authorities, and financing is limited by a reluctance to deploy concessional lending. While American leaders fixate on infrastructure, the Global South views the U.S. as better positioned to support governance and the rule of law, along with improving social services in areas like health and education.

Words and Deeds Must Go Hand-in-Hand to Overcome a Credibility Deficit . Global South leaders are uninterested in a geostrategic tug-of-war between Washington and Beijing or Moscow. They want to hear and see America embrace a pro-development, rather than anti-competitor, strategy. Counterpart countries are less interested in big promises than in seeing America follow through on its commitments, be responsive to partner priorities, and show global leadership in mobilizing strong coalitions.

This paper aims to answer several critical questions:

- How have U.S. development assistance priorities and practices evolved? What pain points undercut America’s ability to use this tool to advance its interests?

- In a competitive marketplace, how attractive is the U.S. offer as a preferred partner and development model vis-a-vis the alternatives?

- What lessons might we draw to strengthen U.S. development assistance efforts in the future and better align supply with demand?

BRI: Belt and Road Initiative

CDC: Center for Disease Control

Commerce: U.S. Department of Commerce

Defense: U.S. Department of Defense

DAC: Development Assistance Committee

Energy: U.S. Department of Energy

F Bureau: State Department Office of U.S. Foreign Assistance

Labor: U.S. Department of Labor

MCC: Millennium Challenge Corporation

NSC: National Security Council

ODA: Official Development Assistance

OECD: Organization for Cooperation and Development

OOF: Other Official Flows

OPIC: Overseas Private Investment Corporation

PEPFAR: President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)

PRC: People’s Republic of China

State: U.S. Department of State

Treasury: U.S. Department of Treasury

USAID: U.S. Agency for International Development

USDA: U.S. Department of Agriculture

USDFC: U.S. Development Finance Corporation

USG: U.S. Government

USTDA: U.S. Trade and Development Agency

2. Strategic Directions, Authorizing Mandates, and Operational Practices

2.2 Post-Cold War & 9/11 Era (1992-2009)

2.3 Contemporary Era (2010-2023)

3. Supply Versus Demand: Development Assistance in a Crowded Marketplace

3.1 The Supply Side: How America Deploys its Assistance Compared to its Peers

3.2 The Demand Side: How Leaders in the Global South Assess America’s Model and Offer 3

4. Development Assistance Today: Learning from the Past, Looking to the Future

Lesson #1: Pivot From Strategic Ambiguity to Strategic Candor

Lesson #2. Move From Operational Incoherence to Operational Complementarity

Lesson #3. Shift Accountability from Process to Outcomes

Lesson #4: Don’t Allow Short-Termism to Undercut Long-Term Interests

Lesson #5: Reposition U.S. Assistance to Be Responsive to Market Demand

Lesson #6. Words and Deeds Must Go Hand-in-Hand to Overcome a Credibility Deficit

1. Introduction

U.S. development assistance in 2023 is under-resourced, operationally fragmented, and beleaguered by perception problems at home and abroad. What was once a source of strength is now a vulnerability at a time when development assistance is more critical to America’s national security than ever before. Countries must increasingly work together to navigate overlapping crises and address transnational challenges, all while ensuring progress towards a fairer, greener, and more prosperous world. In an era of great power competition, development assistance has become an arena for contestation as states jockey for influence.

The starting point of any reform effort begins with a sound diagnosis of where we are and how we got here. This paper takes a retrospective look at U.S. development assistance at three critical junctures: the Cold War (1946-1991), the post-Cold War and 9/11 period (1992-2009), and the contemporary era (2010-2023). It discusses how counterparts in the Global South perceive the U.S. as a development assistance supplier in an increasingly crowded marketplace.

Rather than an exhaustive history, this chapter is a scene-setter: baselining the state of play, identifying what is working, what is not, and why, and surfacing lessons in how we might think and work differently to strengthen U.S. development assistance in the future. The focus of this first chapter is primarily on the U.S. government (USG), while Chapter 2 in this research volume takes a closer look at the private sector.

This analysis employs a mixed methods approach: (i) in-depth background interviews with policymakers and practitioners; (ii) desk research to evaluate assistance strategies, policies, and practices; and (iii) quantitative analysis of U.S. development financing and a global perceptions survey conducted by AidData in 2023.

Section 2 provides a limited historical overview of how U.S. development assistance priorities and practices have evolved from the Cold War to today. Section 3 assesses U.S. development assistance within a broader marketplace, along with insights on how counterparts in the Global South perceive this offer. Section 4 concludes by surfacing several forward-looking lessons and takeaways from this retrospective analysis.

|

Note on Terminology: This paper examines how the USG supplies grants, loans, and other debt instruments, along with in-kind and technical assistance, to support development in other countries. Both Official Development Assistance (ODA) (i.e., grants and no- or low-interest loans referred to as 'aid') and Other Official Flows (OOF) (i.e., loans and other debt instruments approaching market rates referred to as 'debt') are included in this discussion, as are humanitarian and long-term development assistance. Military aid is excluded. For ease of reading, the paper uses generic terms “development assistance” and “aid” as catchalls for these various and diverse instruments. In instances where the particular modality matters (i.e., grants versus loans), the paper uses more specific terms to avoid confusion. |

2. Strategic Directions, Authorizing Mandates, and Operational Practices

U.S. foreign assistance agencies have an overabundance of strategies and plans—at region, sector, agency, and even interagency levels (USAID, 2023). Nevertheless, there is a dearth of high-level strategic guidance to build consensus and coherence around (i) what U.S. development assistance should achieve; (ii) how this instrument of national power should work in harmony with others in the toolkit to advance America’s interests; and (iii) how each agency’s contributions add up to more than the sum of their parts.

Some of this status quo reflects uncertainty and unease over the fact that U.S. development assistance is not an end in and of itself but a means to advance four enduring national interests:

- The U.S. has a humanitarian interest to improve the lives of citizens in other countries and strengthen the ability of governments to deliver peace, prosperity, and stability.

- The U.S. has a security interest in protecting Americans from harmful spillovers due to poverty and fragility, natural disasters, eroding democracies, and climate change.

- In an era of geostrategic competition, there are reputational benefits from America building goodwill with foreign leaders and publics, which advances diplomatic interests .

- The U.S. has an economic interest in seeing countries become more prosperous and open two-way trade, investment, and innovation as a boon to the American economy.

2.1 Cold War Era (1946-1991)

As early as the 1930s and 40s, American leaders promoted a liberal, capitalist world order as vital to securing U.S. national interests. In the aftermath of World War II, the potential for communist parties to exploit economic discontent in war-torn Europe and farther afield threatened this order and hastened the emergence of the development assistance architecture we have today. A succession of U.S. presidents, Republican and Democrat, saw development assistance as strategically valuable for advancing America’s national security, with varying degrees of initial skepticism. Development assistance began as a “temporary expedient” (Lancaster, 2007) but became an enduring tool in the U.S. foreign policy arsenal. Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy made a series of consequential decisions, setting the U.S. down a multi-decade path to become the largest supplier of development assistance.

A combination of factors triggered a strategic reset in the 1970s and 80s: concerns regarding the spread of communism diminished, critics raised the alarm that U.S. development assistance was not effective in improving the lives of the poor, and the U.S. public became more cognizant of how humanitarian and debt crises affected other countries. New strategic imperatives arose as Presidents Carter, Reagan, and Bush embraced aid as an inducement for peace in the Middle East or to incentivize economic reforms. Long-standing aims endured, such as the U.S. interest in promoting a rules-based order of democratic values, free markets, and private sector-led development. Executive and Congressional leaders commissioned studies and committees to improve the effectiveness of U.S. development assistance, but few reform efforts took off. Legislators added new organizations and requirements for how funds were to be used.

2.1.1 Stated Priorities in the Cold War

In 1947, Truman convinced Congress to provide US$400 million in economic assistance to repel a communist insurgency in Greece and Moscow’s territorial claims in Turkey (Lancaster, 2007). He galvanized Congressional support for a US$13.3 billion Marshall Plan to support post-war recovery and reconstruction in Western Europe. (ibid). Primarily grant-based financing, the 1948 Economic Recovery Act was generous-spirited but not without strings. It furthered commercial interests by requiring countries to reduce trade barriers for U.S. goods. Wary of the 1949 communist revolution in China and the outbreak of conflict on the Korean peninsula, Truman’s 1951 Mutual Security Program expanded assistance to Asia (ibid).

Beyond these geographically bounded efforts, Truman announced the first global U.S. foreign aid program in his 1949 inaugural address (the Point Four Program). The Foreign Economic Assistance Act of 1950 laid the legislative groundwork for this technical assistance program, which shared U.S. scientific and industrial knowledge to convince the world’s emerging economies of the benefits of market-based democracy (Gates, 2020). U.S. leaders took great pains to emphasize that to succeed in this ambitious undertaking, technical assistance must be a shared enterprise with government agencies working in collaboration with the private sector.

Eisenhower initially promised to pursue a ‘trade not aid’ agenda but instead doubled down on assistance to safeguard Cold War alliances and counter an assertive Soviet Union intent on expanding its sphere of influence (Lancaster, 2007). In 1954, he won Congressional support to create a food aid program (Public Law 480), redeploying agricultural surpluses on concessional terms to assist countries facing food shortages and benefit U.S. commercial interests (ibid).

Eisenhower also expanded low-cost financing to bankroll development projects through the 1957 Development Loan Fund and two multilateral efforts: the World Bank’s International Development Assistance no or low-interest loan window in 1958 and the Inter-American Development Bank. His motivation was partly hard-eyed realism, the need to temper anti-American sentiment in Latin America and the world (ibid). The timing was significant as the Soviet Union began to scale its technical assistance offerings to the developing world.

Kennedy has had the most enduring influence on the architecture of U.S. assistance. Declaring a new “Decade of Development,” he worked with Congress to pass the 1961 Foreign Assistance Act, merging the Eisenhower-era Development Loan Fund and International Coordination Agency into the Agency for International Development (USAID) (Lancaster, 2007). The 1961 act vested the President the authority to decide how aid is delivered but banned assistance to communist countries or those engaged in gross violation of human rights. It left the Department of Treasury (Treasury) responsible for multilateral development banks. It placed USAID in a somewhat ill-defined position as a semi-independent agency at the sub-cabinet level, reporting to the President via the Secretary of State, who provides policy guidance. The 1961 act remains the authorizing rationale for U.S. assistance today.

Like his predecessors, Kennedy valued foreign aid as an instrument of national power to promote economic growth that would buttress countries against the lure of communism. Kennedy was concerned that Fidel Castro’s charismatic populism would win over countries in the Western Hemisphere (Lancaster, 2007). His 1961 Alliance for Progress in Latin America intended to achieve a double benefit: investments in education or infrastructure projects would not only help other countries modernize their economies and societies but do so in ways that would also reduce the appeal of communism (ibid). His formation of the Peace Corps that same year follows a similar logic to public diplomacy programs: it put a human face on U.S. assistance by sending American volunteers abroad to support community-based development projects in ways that build personal relationships and goodwill between the people of two nations.

By the mid-1960s, U.S. bilateral development assistance comprised three programs: Development Assistance (allocated and managed by USAID); Security Supporting Assistance, which later became the Economic Support Fund (disbursed by State but managed by USAID); and Food Aid (initially issued by an interagency group but managed primarily by USAID). Criticisms of U.S. development assistance grew louder and more high-profile: uncertainty over whether investments were benefiting the poor; concerns over balancing multiple objectives for aid programs; arguments that multilateral channels were more effective than bilateral channels to deploy assistance; and assertions that aid was no longer necessary as the intensity of the competition with the Soviet Union abated.

Johnson and Nixon formed committees, the General Advisory Committee on Foreign Assistance Programs or Perkins Committee and the Peterson Commission, respectively, to conduct studies and recommend reforms (Lancaster, 2007; Nowels, 2007). Both committees suggested greater emphasis on working through multilateral channels, among other recommendations, to improve the effectiveness of U.S. assistance dollars in achieving development goals (Asher, 1971). Nixon adopted some of these recommendations in proposals to Congress, but they failed to resonate. Congressional leaders were dissatisfied and refused to reauthorize aid on multiple occasions (Nowels, 2007). It took the “New Directions Legislation” (1973 Foreign Assistance Act) to break the logjam. The legislation restructured U.S. assistance to emphasize the basic needs of the rural poor in critical sectors (e.g., education, agriculture, population, energy, environment) (ibid).

Policymakers added more development assistance organizations during this time. The Foreign Assistance Act of 1969 authorized the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) to crowd in private sector support for development by helping companies manage risk associated with foreign direct investment and gain footholds in new markets to spur economic growth at home and abroad. The legislation established the Inter-American Foundation as an “experimental program” to fund community-led development activities in Latin America and the Caribbean.

President Carter formed the International Development Cooperation Agency in 1979 as an “umbrella organization” to oversee and coordinate all development assistance programs. However, the agency lacked sufficient authority to realize this vision in practice. Citing the Inter-American Foundation as a success, the African Development Foundation Act of 1980 created an independent agency with a similar structure and ethos in supporting locally-led grassroots development activities but adapted to the needs of Africa.

In the 1970s and 1980s, shifts in the broader geostrategic landscape influenced how the American public and political leaders thought about the purposes of aid. Americans were transfixed by images and stories of humanitarian disasters, from droughts in Ethiopia to floods in Bangladesh, stoking popular support for the U.S. to provide relief (Lancaster, 2007). A conflict between Egypt, Syria, and Israel prompted the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries to mount an oil embargo, quadrupling oil prices with several cascading effects: foreign exchange shortages for petroleum importers, rising commodity prices, unsustainable borrowing, and widespread debt crisis. Ford and Carter embraced aid as an inducement for peace in the Middle East. Reagan overcame his predisposition to reduce aid dramatically and oversaw a significant increase in bilateral assistance. He came to appreciate aid as a means of shoring up sympathetic governments in Latin America in the face of “leftist challenges” and creating financial incentives for partner countries to enact politically difficult economic reforms.

To professionalize the delivery of development assistance, executive branch agencies adopted new ways of working: introducing official development strategies and policies to guide their efforts, including an assessment of economic conditions and a theory of change (i.e., logical frameworks) to inform programming, as well as investing in project evaluation and engaging with other members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC).

Both executive and congressional leaders continued to form new committees to study development assistance and recommend reforms. Reagan appointed the 1983 Carlucci Commission to clarify the relationship and roles of development versus security assistance, while the House Foreign Affairs Committee gave the Hamilton-Gilman Task Force of 1988-89 to reexamine objectives, roles of Congress versus the executive branch, and restrictions on financing and budgets shaping how U.S. development assistance was designed and delivered.

2.1.2 Revealed Priorities in the Cold War

Between 1946 and 1991, the United States obligated nearly US$1.1 trillion (constant USD 2019) in economic assistance or about US$23.7 Bn per year on average over 46 years. Asia and Western Europe each attracted roughly one-quarter of this assistance in the Cold War era. [2] The Middle East and North Africa region came in third (13%). The largest country recipients closely align with the stated priorities of congressional and executive leaders: support post-war economic recovery in Europe, bolster allies to withstand the spread of communism in Asia, and secure peace in the Middle East. Development and military assistance went hand-in-hand: the ten largest country recipients of development assistance dollars also received the most military aid. Comparatively, other regions of the world tended to receive more assistance from the U.S. through economic (rather than military) aid.

Of course, money is only one indication of relative priority. If we look at the number of USG agencies funding development activities in a country, we see a very different story. Twenty-one countries had 7 to 8 USG agencies operating within their borders during the Cold War era. However, the profile of these countries is decidedly different from the large dollar recipients above, as they are predominately in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, along with India. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the countries with the fewest agencies involved are those with relatively small populations.

2.2 Post-Cold War & 9/11 Era (1992-2009)

The fall of the Soviet Union sparked discussion and debate over the continued utility of development assistance in advancing America’s national interests abroad with the shift from a bipolar to a unipolar world. Nevertheless, even as leaders across the political spectrum debated the aims, budgets, and structure of aid, they oversaw more than a two-fold increase in the number of USG agencies involved in development assistance in U.S. history—from 8 in the Cold War to 20 in the post-Cold War and 9/11 era.

Absent a single animating threat to unify disparate political interests, U.S. development assistance in the 1990s navigated two countervailing forces. Congressional and executive branch leaders explored new use cases for development assistance dollars: help post-Soviet states transition to market-based democracies, promote democracy to strengthen international security, tackle global public goods like the environment and HIV/AIDS, and facilitate peaceful reconstruction after prolonged conflicts. Meanwhile, development assistance dollars and agencies became attractive targets for leaders to reduce the size and cost of the federal government, on principle (the desire for a smaller government) or pragmatism (the need to tackle the national deficit).

In the early 2000s, American leaders faced a fundamentally different geostrategic playing field: instability and terrorism threatened to undermine the international rules-based order. The 9/11 terrorist attacks made Americans acutely aware that conflict and discontent with U.S. policies abroad could harm their daily lives at home. Policymakers saw development assistance as a critical instrument in tackling root issues of poverty and inequality that, if left unaddressed, could metastasize into tyranny, violence, and extremism.

The transition to a 24-hour news cycle and increasing accessibility of international travel made it easier for the American public (and their elected officials) to learn about other countries. Faith-based groups, particularly the Christian right, became vocal about their desire to see the U.S. providing relief to countries in crisis in grappling with everything from natural disasters to debt forgiveness and public health challenges like HIV/AIDS. Political leaders became more aware of the need to counterbalance an increasingly assertive (and preemptive) military posture with visible acts of generosity to win the hearts and minds of foreign publics.

2.2.1 Stated Priorities in the Post-Cold War and 9/11

President George H.W. Bush saw that development assistance could help non-communist parties in Eastern Europe and post-Soviet states transition to free market democracies with multiparty elections (Lancaster, 2007). In this vein, the U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA) was established in 1992 as an independent agency via the Jobs Through Exports Act. USTDA blended a commercial and developmental mission to promote exports of U.S. goods and services to support sustainable infrastructure development and economic growth in emerging economies. The roots of USTDA began as a program initially overseen by USAID in the 1970s to broker access to U.S. technical assistance, technology, and equipment to emerging economies.

His successor, President Bill Clinton, argued it was time for the U.S. to enjoy a “peace dividend” and redeploy its resources to support “government reinvention” at home, curbing debt-fueled spending to rebalance the federal budget (Norris, 2014). Clinton’s position on foreign aid was a defensive maneuver: he believed that Bush’s failure to win a second term was due to growing discontent among the American public that Bush had paid insufficient attention to domestic concerns (ibid). The administration was hesitant to highlight development assistance in high-level speeches (Lancaster, 2007).

President Clinton asked Clifford Wharton to redesign U.S. development assistance for the post-Cold War reality. The Wharton report focused on process issues that inhibited the effective delivery of aid, such as earmarking and directives in appropriating the development assistance budget and removing other restrictions (Nowels, 2007). It informed the draft Peace, Prosperity, and Democracy Act in 1993, which later stalled in Congress.

Much of the Clinton administration’s track record on development assistance was dictated by a contentious relationship with Congress. U.S. agencies had their budgets drastically slashed, personnel numbers reduced, and morale tested as political leaders debated eliminating USAID (Gates, 2020). Clinton’s Secretary of State Warren Christopher sought to wrest control of foreign aid resources away from USAID, suggesting that Vice President Gore “lead a study on the issue of merging USAID into State” (Lancaster, 2007). Ultimately, the Foreign Affairs Reform and Restructuring Act of 1998 abolished the International Development Cooperation Agency (the Carter-era coordination body for development assistance) and established USAID as an independent agency under the authority of the Secretary of State.

The Clinton administration still enacted several executive-branch-led reforms and innovations. It closed USAID missions in 26 countries (Norris, 2014). Clinton established the Office of Transition Initiatives to support nations in conflict moving from near-term stabilization to long-term development (Savoy & Yayboke, 2017). Perhaps the most ambitious effort was Plan Colombia (the Andean Counterdrug Initiative of 2000). By the late 1990s, the U.S. was reaping the rewards of its fight against debt-financed spending and enjoying a budget surplus. This fiscal flexibility created a window of opportunity to help a key partner in Latin America forestall a collapse in their democratic governance.

President Clinton galvanized bipartisan support from Congress by linking the American public’s concerns over drug addiction to tackling illicit coca production and narcotics trafficking in Colombia (Shifter, 2012). This argument was compelling—an estimated 90 percent of cocaine making it to the United States came from Colombia (ibid). There was a geostrategic element for those concerned about instability in the Western Hemisphere as illicit coca production and trafficking financed armed revolutionary groups. The activities of these groups had prompted a mass exodus from the country, providing a development imperative for action.

Plan Colombia was imperfect. It garnered criticisms for civilian casualties in counter-insurgency campaigns and deemphasizing Colombia’s domestic economic and security needs relative to America’s focus on curbing coca production (ibid). Nevertheless, importantly, it demonstrated how the U.S. could pool resources with counterparts to tackle a big challenge, which straddled development and security concerns in ways that advanced the interests of both countries.

President George W. Bush changed the tenor of discussion around U.S. development assistance. In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, he elevated development as one of three priorities within the 2002 National Security Strategy, alongside defense and advancing democracy abroad. Bush matched his rhetoric with decisive action: announcing ambitious goals, including an annual $5 billion increase in funding for a new compact for global development (the Millennium Challenge Account) and US$15 billion to help countries fight HIV/AIDS (Lancaster, 2007). He was uniquely willing to put his political capital on the table to personally lobby Congressional leaders to get this done, which was likely critical to his success (ibid). Bush’s 2006 National Security Strategy enshrined promoting human rights, freedom, and democracy as one of two pillars to guide U.S. foreign policy for his second term in office (Daalder, 2006).

The issue of what to do about USAID continued in the early 2000s as Bush experimented with new agencies, offices, and coordination vehicles. Some structures were temporary (e.g., the Iraq Coalition Provisional Authority), while others stayed within the confines of an existing agency, namely the Coordinator for Reconstruction and Stabilization at State (Brainard, 2007). However, there were also several new players with more substantial authority, political constituencies, and staying power. These players also shared a commonality of clawing back control over elements of the development agenda traditionally managed by USAID and signaling a lack of confidence in the agency.

The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) was established in January 2004 with the passage of the 2003 Millennium Challenge Act. The legislation, instigated by President Bush, created a government entity with the mandate to promote economic growth, reduce poverty, and strengthen institutions in ways that support stability in partner countries. In a departure from the expectations set for USAID, MCC’s design allowed the agency to be selective about where it worked, provide time-limited grants (compacts), design projects responsive to country priorities and solutions rather than Congressional or executive branch mandates, screen projects using cost-benefit analyses, and transparently evaluate results (Parks, 2019). MCC uniquely operates as a “wholly-owned corporation headed by a Chief Executive Officer and reporting to a Board of Directors composed of State, USAID, Treasury, the CEO, and four private sector individuals” (Custer, 2022).

Again personally championed by President Bush, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) was formed in 2003 with the passage of the U.S. Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Act (Morison, 2007). The legislation uniquely endowed the Office of the PEPFAR Coordinator with significant budget authority over global health funding to combat these three diseases and elevated its political prominence as a seventh-floor entity within the State Department (Brown, 2022). The PEPFAR Coordinator position and office shared similarities by design with anti-terrorism task forces, which have the authority and operational capacity to nimbly deploy resources quickly across large geographies and with myriad partners (ibid).

Today, USAID is one of the largest implementers of programs funded by PEPFAR, along with the Center for Disease Control (CDC), National Institutes of Health, Labor, Commerce, Defense, and the Peace Corps (KFF, 2023; Savoy & Yayboke, 2017). PEPFAR has been reauthorized multiple times via the 2008 Lantos-Hyde Act, the 2013 Stewardship Act, and the 2018 PEPFAR Extension Act. However, PEPFAR faced substantial headwinds in 2023 as legislators struggled to mobilize a bipartisan majority to renew the program’s authorization set to expire in September for another five years. Should Congress fail to pass a reauthorization in time, PEPFAR would continue. Still, several of its time-bound provisions related to how HIV/AIDS funding is allocated, the U.S. contribution to the Global Fund, and reporting oversight would sunset (Moss & Kates, 2023).

Occasionally, congressional and executive branch leaders conveyed more confidence in USAID’s ability to shepherd important interagency initiatives. For example, the President’s Malaria Initiative, led by USAID and co-implemented with the CDC within the Department of Health and Human Services, helped countries in sub-Saharan Africa control and eliminate malaria by delivering cost-effective, life-saving malaria interventions and technical assistance.

One of the more contentious decisions was the 2006 formation of the Office of U.S. Foreign Assistance (F Bureau) under Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. The office oversees and coordinates U.S. development assistance resources focusing on policy, planning, performance management, and strategic direction. Critics saw this as an attempt to strip USAID of policy, planning, and budget functions and transfer these responsibilities to the State Department.

2.2.2 Revealed Priorities in the Post-Cold War and 9/11 Period

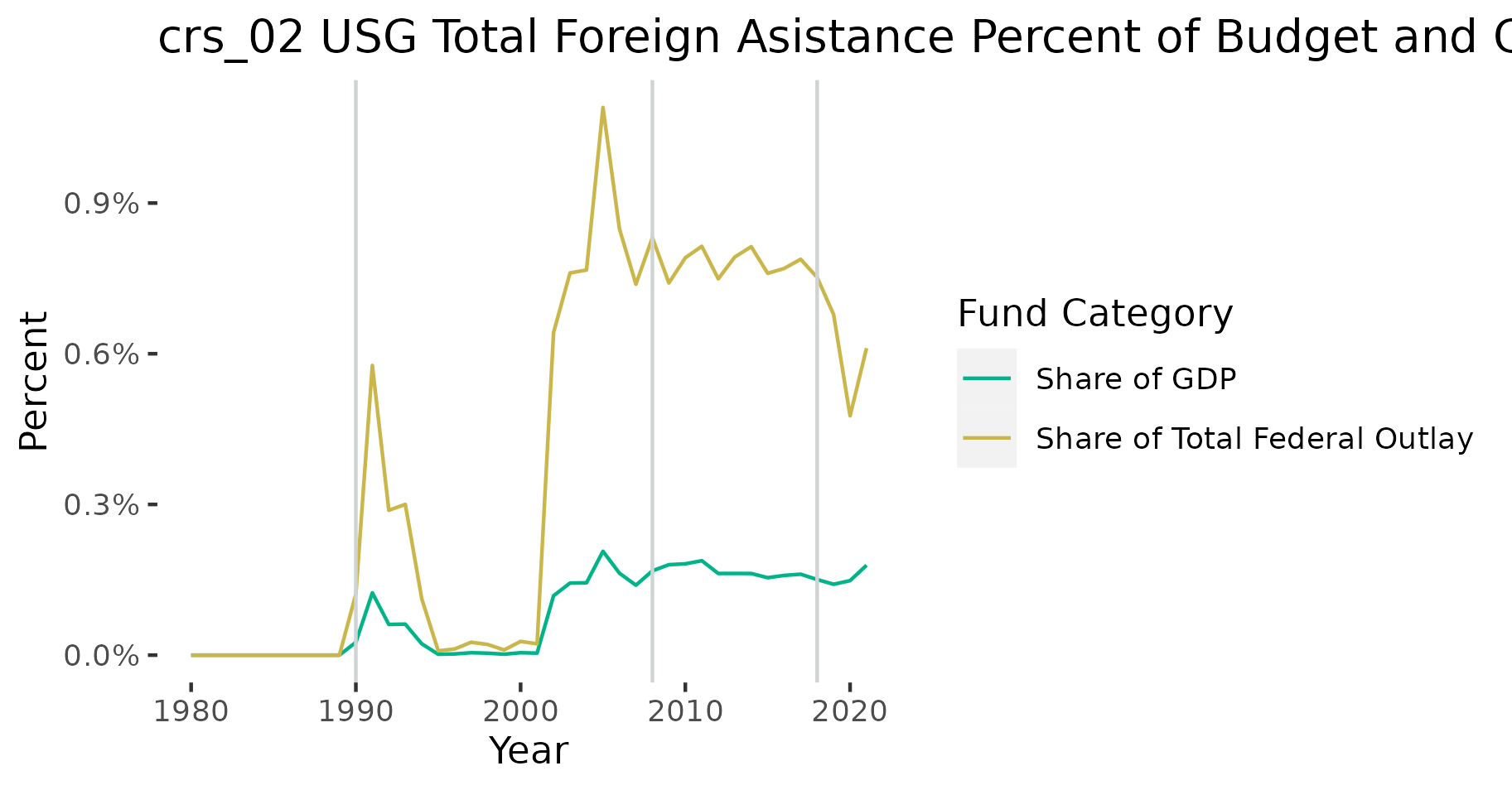

The USG obligated US$23.5 Bn (constant USD 2019) per year to development assistance between 1992 and 2009: roughly US$0.2 Bn less per year on average for a total of US$423 Bn (constant USD 2019). [3] However, this average obscures a high degree of volatility: the plummeting share of the total federal outlay in the 1990s coincided with the strategic ambiguity over the utility of aid in the Clinton administration. In comparison, the dramatic upswing in development assistance dollars in the early 2000s corresponded with George W. Bush’s elevation of development as central to U.S. national interests (Figure 1). [4]

Figure 1. U.S. Development Finance as a Share of GDP and Federal Spending (1980-2021)

Sources: OECD Creditor Reporting System (1980-2021). Overall federal expenditures were obtained from the Office of Management and Budget’s Historical Table 4.1—Outlays by Agency (1962-2027).

Noticeably, 5 of the 10 top country recipients of U.S. assistance dollars during this period had relatively large Muslim populations: Afghanistan, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Pakistan, and Sudan. This budget allocation was consistent with leaders’ stated desire to rebuild goodwill in the Arab and Muslim world and deter future terrorist threats. The continued emphasis on Egypt and Israel signals lasting interests in securing peace in the Middle East, while the emergence of Russia as a primary recipient of development assistance was in step with U.S. diplomatic rhetoric to support the country’s transition to a free market democracy following the fall of the Soviet Union. Unsurprisingly, Colombia was also one of the largest recipients of economic assistance during this time, consistent with the robust bipartisan support for Plan Colombia since 2000.

Once again, the top ten economic assistance countries also received the most military aid. Beyond the top recipients, the regional distribution shows a marked change in the focus of U.S. economic assistance in line with the stated aims of political leaders. The Middle East and North Africa attracted nearly one-quarter of the U.S. economic assistance budget, jumping ahead of Asia (11 percent) and Western Europe (less than 1 percent).

Strikingly, the post-Cold War and 9/11 era was notable for another reason: USG agencies funding overseas development activities more than doubled—from 8 to 20. Although many of these agencies had specific geographic focuses, the number of agencies operating in a single country also grew from 4 to 9 on average, increasing the coordination burden for those receiving this assistance. The implications were particularly stark for the top nations on this measure, which had 15 to 17 USG agencies operating in their borders during this time.

If the number of agencies indicates revealed priority, then these show a greater emphasis on Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, along with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Russia, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine. Post-Soviet countries attracted the most significant uptick in the number of agencies they were engaging with during this time, perhaps reflecting the U.S. emphasis on supporting their transition to market democracies. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the countries with the fewest agencies involved were those with relatively small populations or where there was a shift in priorities (i.e., pivot away from post-war reconstruction in Europe).

2.3 Contemporary Era (2010-2023)

2.3.1 Stated Priorities in the Contemporary Era

President Barack Obama carried forward his predecessor George W. Bush’s emphasis on global health when he assumed office in 2009. However, reminiscent of Bill Clinton’s approach to galvanize bipartisan support for Plan Colombia, Obama argued in his 2010 national security strategy that “when a child dies of a preventable disease, it offends our conscience; when a disease goes unchecked, it can endanger our health.” In other words, we have a moral interest and a strategic one to strengthen health systems in other countries: Americans are made safer by ensuring that pandemics and infectious diseases do not reach our shores (CFR, 2010). Obama also emphasized the instrumental use of development assistance within a more considerable effort to stop conflict, counter criminal networks, and grow the ranks of prosperous, democratic states that will be capable partners in helping the U.S. address global challenges (White House, 2010).

Later that same year, Obama released a Presidential Policy Directive on Global Development to lay out his vision of sustainable development through investing in broad-based economic growth, democratic governance, and game-changing innovations (e.g., vaccines, clean energy, weather-resistant seeds). The U.S. would embrace a new operational model to be an effective partner to accomplish this idealized future. The features of Obama’s model noticeably echoed refrains of the design of MCC but scaled to U.S. development assistance writ large: greater selectivity in sectors and countries; stronger emphasis on country ownership, responsibility, and priorities; and systematically tying resources to results.

Obama argued that for this strategy to succeed, the U.S. must elevate development, alongside defense and diplomacy, “as indispensable in the forward defense of America’s interests.” He identified several mechanisms in an attempt to ensure coherence across the interagency players involved in development assistance and other elements of foreign policy: a Global Development Strategy every four years, an integrated Quadrennial Defense, Diplomacy, and Development Review (conducted in 2010 and 2015), an Interagency Policy Committee on Global Development reporting to the Deputies and Principals Committees of the National Security Council (NSC), and included the USAID Administrator in relevant meetings.

By 2015, Obama’s second national security strategy saw the resurgence of great power rivalry and global terrorism as existential threats to U.S. interests in an “age of upheaval” (White House, 2015). Obama identified a list of strategic risks for U.S. action. Many of these risks fell (at least in part) within the remit of development assistance: confronting climate change, averting a global economic crisis, curbing infectious disease outbreaks, reducing instability in weak or failing states, and preventing energy market disruptions. Taking a defensive posture in response to criticism of the administration’s policies on Syria and Iraq (Patrick, 2015), Obama argued that “strategic patience” was needed in America’s approach to helping countries transition from conflict and crisis to build robust institutional foundations for future stability.

In the tradition of past presidents, Obama promoted signature initiatives or innovations to advance the administration’s key priorities—some of which fizzled out quickly, but at least two that enjoyed relative success and staying power across two subsequent administrations. The first was Feed the Future, based on Obama’s pledge at the 2009 G8 Summit to mobilize US$3.5 Bn over three years to combat food insecurity due to skyrocketing world prices (Lawson et al., 2016). Led by USAID and implemented with ten USG agencies, along with private sector and civil society partners, Feed the Future promotes food security beyond emergency food aid and helps 19 focus countries boost agricultural yields and improve market access (ibid).

Feed the Future incorporates elements from the MCC playbook: country selection using predetermined criteria, emphasis on country ownership and performance, and a commitment to managing for results with transparently published standard metrics to monitor, evaluate, and justify its investments (ibid). The initiative is imperfect—interagency roles are ill-defined, and using performance data to make decisions leaves much to be desired (Lawson et al., 2016; GAO, 2021). Nevertheless, Feed the Future has charted successes: “it helped lift 23.4 million people out of poverty, prevent stunting in 3.4 million children, and create opportunities for 5.2 million families no longer suffering from hunger” (Speckhard, 2020).

Critical to its longevity, Feed the Future won congressional support to institutionalize the program via the Global Food Security Act of 2018 and the Global Food Security Reauthorization Act of 2022. Feed the Future also crowded in nine other bilateral and private philanthropic donors to pool resources towards shared goals via the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program, a multi-donor trust fund operated by the World Bank (2023).

Power Africa is a second Obama-era innovation that has earned hard-won bipartisan praise. With a commitment to double access to electricity in Sub-Saharan Africa (White House, 2015), the initiative launched in 2013 has charted notable wins over the last decade: electricity access for 18 million homes and businesses and 11,000 megawatts of power generated (Auth et al., 2021). Power Africa demonstrated that the USG could be an effective partner: it crowded in “billions of dollars of private sector capital,” inspired public and private sector actors en masse in the U.S. and Africa to cooperate towards a single animating goal, and promoted Africa as an attractive destination for future investments in clean energy generation (ibid).

One of the hallmarks of Power Africa was the White House political leadership saying, ‘we’re going to do this’ and holding agency bureaucracies accountable to get it done—a trait shared by similar success stories like PEPFAR and MCC in the George W. Bush era. Like other initiatives with staying power across administrations, what began as an executive branch innovation was fully institutionalized via the 2015-2016 Electrify Africa Act, which passed Congress with bipartisan support.

Power Africa has yet to realize its ambitious goal of adding 30,000 megawatts of clean energy, and it faces headwinds in 2023 as the initiative must evolve to navigate new challenges posed by COVID-19, rapid African urbanization, and climate change (Auth et al., 2021). Nevertheless, many Republicans and Democrats are interested in replicating the initiative’s success in harnessing private sector, interagency, and civil society cooperation around a single issue and applying this model to tackle grand challenges in other sectors (e.g., food production, vaccine production, closing the digital divide). Others urge caution and argue that America should focus on delivering on consequential energy sector commitments before scaling further.

The Obama administration also put in place more modest innovations that were consequential in other ways. It promoted greater transparency around U.S. development assistance efforts by launching the Foreign Aid Database in 2010 and signing the Foreign Aid Transparency and Accountability Act in 2016. The administration set in motion a USAID Forward reform agenda to deliver results at scale, achieve sustainable development with partnerships and locally-led solutions, and mainstream breakthrough innovations. Essential features of these reforms included the use of Country Development Cooperation Strategies, evaluations to inform forward-looking planning, and the Development Innovation Ventures fund to test and scale innovations based on results.

The Obama administration also piloted a mechanism to attract specialized talent via the Presidential Innovation Fellows program, which recruits “leading entrepreneurs, innovators, developers, designers, and engineers” from the private sector for a limited-term placement in federal government agencies (White House, 2015). Obama launched the program in 2012 and made it permanent with his 2015 executive order.

The ascendance of President Donald Trump in 2016 changed the game for development assistance in several ways. Many U.S. presidents and political leaders have justified overseas development as instrumental to advancing U.S. national interests. However, President Trump took this a step further, saying that U.S. foreign policy, including development assistance, would prioritize America’s interests “first” and above all others. In this vein, Trump’s 2017 national security strategy argued that the U.S. would prioritize its development assistance based on alignment with U.S. interests. Initially, the Trump administration sought to curtail U.S. development assistance aggressively: it proposed budget cuts of nearly one-third for State and USAID. It pursued a reorganization plan that considered merging USAID into State (Ingram, n.d.).

Trump’s 2017 national security strategy showed that his primary interest in development assistance was to advance U.S. influence abroad, particularly given heightened competition with “adversaries” like the PRC and Russia. Unlike his immediate predecessors, democracy promotion and climate change largely vanished from Trump’s agenda, replaced with an emphasis on economic progress. Trump’s strategy signaled selectivity differently: prioritizing countries based upon alignment with U.S. interests (e.g., free market, the rule of law, fair and reciprocal trade). Finally, though past presidents acknowledged their desire to broker effective partnerships with the private sector, Trump was more explicit in stating his intent that America would “shift away from reliance on assistance based on grants to approaches that attract private capital.”

The Trump administration’s most significant development assistance reform was the creation of the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). Established in 2019, following the passage of the 2018 Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development Act, the DFC integrated the capabilities of the former OPIC and USAID’s Development Credit Authority to create new financial products to reduce barriers to entry for U.S. companies to invest in low- and middle-income countries.

Unlike other U.S. development assistance agencies, which deal primarily in grants, the DFC offers loans, loan guarantees, political risk insurance, equity investments, and technical cooperation. Furthermore, the legislation doubled the agency’s total cap (i.e., the money it can invest) from US$29 Bn to US$60 Bn. Chapter 2 offers a more in-depth look at some of the DFC’s early successes, challenges, and lessons in mobilizing private sector capital.

The Journey to Self Reliance, a second Trump-era reform championed by then USAID Administrator Mark Green, sought to fundamentally change how the agency decided where to work, how to work, and to what ends. The initiative envisioned countries moving along a continuum towards greater self-reliance: having sufficient “capacity to plan, finance, and implement solutions to local development,” as well as the “commitment to see these solutions through effectively, inclusively, and with accountability” (Runde et al., 2021).

Several Journey to Self Reliance innovations share similar ingredients critical to MCC’s success. The Journey to Self Reliance Country Roadmaps, a diagnostic tool for assessing country progress, parallels MCC’s country scorecard. The emphasis on treating counterparts as equal partners and co-creators (ibid) echoes MCC’s operating principle of country ownership. The idea that countries could become less reliant on development assistance opened the door for USAID to be selective in recalibrating its programs based on partners’ relative needs and the opportunity for progress.

When President Joe Biden took office in 2021, he faced a formidable challenge—a global pandemic, COVID-19. Biden’s decision to give USAID Administrator Samantha Power a permanent seat at the table in the NSC Principals Committee sent a powerful signal that issues of development assistance would factor into broader discussions of U.S. foreign policy at the highest levels. Trump similarly gave Administrator Mark Green a formal role in the decision-making body but at a somewhat lower level: the Deputies Committee (Igoe, 2021).

In his 2022 national security strategy, Biden references foreign assistance by name three times in the context of helping partner governments fight corruption, supporting global health security through investing in early warning and forecasting for infectious diseases, and providing countries with access to sound, sustainable financing (in contrast to debt-fueled spending at unsustainable interest rates). Development finance was referenced once concerning embedding climate change into investment strategies. Biden emphasized cooperation with like-minded democracies to compete with “adversaries and autocracies” provided a very explicit framing of U.S. foreign policy, including development assistance, as seeking to counter malign foreign influence in ways reminiscent of countering communism in the Cold War.

With this strategic backdrop in mind, President Biden announced a new Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment at the G7 Summit in 2022 as one of the administration’s signature development initiatives. Biden pledged to mobilize US$200 billion in U.S. financing across grants, private sector investments, and other project funding over the next five years (White House, 2022). As of May 2023, the initiative had mobilized US$30 billion via grants, federal financing and leveraging private sector funds (White House, 2022b). The partnership’s focus areas are consistent with the administration’s stated priorities more broadly: promoting investments in clean energy and responsible extractives in a climate-friendly way; applying a gender-sensitive lens to priority infrastructure in areas such as water and sanitation with outsized benefits to women and girls; ensuring global health security with investments in infrastructure for vaccines production, disease surveillance, and early warning; and safeguarding open digital societies through investments in 5G and 6G connectivity with interoperable, secure, and reliable networks (ibid).

A second Biden initiative, Prosper Africa, builds upon an earlier effort by his predecessor, Donald Trump, to bolster two-way trade and investment between Africa and the United States. The April 2023 reboot of the interagency initiative incorporates 17 participating agencies, deal teams at the mission level, the NSC, and a secretariat to bring USG support to bear in identifying and closing promising trade and investment deals. Consistent with the Biden national security strategy and Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment themes, ProsperAfrica will focus on several focus sectors: energy and climate solutions, global health, and digital technology (Saldinger, 2021). Critics argue that the initiative is more sizzle than substance: putting a bow on something the U.S. is already doing with no new money.

USAID Administrator Samantha Power’s signature initiative has been localization—putting local actors in the lead, strengthening local systems, and responding to local communities (n.d.). One of the more contentious elements of this agenda is Power’s stated goals to channel (i) 25 percent of USAID’s funding to local organizations over the next four years and (ii) 50 percent of funding towards projects that put local communities in the lead (either alone or in partnership with a U.S. organization).

There is broad acceptance across the U.S. assistance community that supporting locally-led development is the right thing to do in theory. In practice, this agenda is politically fraught. Some resistance is the result of path dependence. USAID heavily relies on U.S. civil society and private sector contractors to implement most projects. This dynamic is discussed at length in Chapter 2 of this research volume. Congressionally mandated inspector generals and exhaustive procurement regulations (Federal Acquisition Regulations), intended to ensure taxpayer money is spent wisely, create perverse incentives to award large, multi-year awards to a small coterie of contractors viewed as less likely to misuse the funds.

Localization is primarily a process-driven agenda—emphasizing inclusion, equity, and respect for local voices in the design and delivery of development projects. In some ways, it is an extension of the principles of country ownership that were important to past initiatives like MCC and the Journey to Self-Reliance. The critical difference is that there is less clarity on localization to what end(s) and many implicit assumptions of how this agenda will improve effectiveness and results (Domash, 2022). The U.S. has another blindspot and implementation challenge, as America’s development assistance almost exclusively flows around, not through partner country governments. Over ninety percent of assistance is deployed to non-governmental actors in the U.S. or abroad. As USAID pushes localization, building effective state counterparts is an integral part of the sustainability equation, but it is unclear whether these funds will benefit local governments.

2.3.2 Revealed Priorities in the Contemporary Era

Between 2010 and 2021, the USG obligated US$37.1 Bn (constant USD 2019) per year to development assistance: roughly US$13.6 Bn more per year on average than the previous period for a total of US$445.4 Bn (constant USD 2019). [5] Preliminary estimates indicate that the U.S. will obligate US$130 Bn from 2022 to 2024. [6] There was noticeable consistency in the top country recipients of U.S. economic assistance dollars compared to the previous period. Several countries in the Middle East (Iraq, Afghanistan, Jordan, Pakistan) attracted large dollars related to the ongoing repercussions of the U.S. ‘war on terror’ and continued efforts to secure peace. Syria, South Sudan, Uganda, Nigeria, Kenya, and Ethiopia also came out on top.

Another commonality across these top economic assistance countries was that they tended to receive the most military aid. There was one exception: Egypt primarily received military assistance. Sub-Saharan Africa emerged as the region receiving the largest share of U.S. economic assistance for the first time, accounting for 30 percent of the entire portfolio, followed by Asia (15 percent) and the Middle East and North Africa (12 percent).

The number of USG agencies funding overseas development activities remained at 20 overall and 9 per country on average, consistent with the post-Cold War and 9/11 period. The distribution of agencies involved in each country indicated a revealed priority in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, along with the Philippines and Indonesia. These countries tended to have 17-18 countries operating within their borders during this time.

3. Supply Versus Demand: Development Assistance in a Crowded Marketplace

For almost the entirety of the Cold War and the post-Cold War and 9/11 period, the U.S. was the single largest bilateral supplier of financing for development. In the contemporary era, the relative dominance of the U.S. as a development finance provider began to lessen. More countries joined the OECD’s club of 30+ major donors—the DAC—and collectively, this group began mobilizing a larger share of assistance. In parallel, the PRC arose as a major financier of overseas development. In an increasingly crowded marketplace, U.S. development assistance needs a clear value proposition of what it can offer to counterpart nations and why America is well-positioned to deliver.

In this section, we examine U.S. development assistance from a comparative perspective: the supply of financing America offers relative to the alternatives and the nature of the demand as evidenced by a 2023 survey of leaders from 129 low and middle-income countries on their preferred partners and development models.

3.1 The Supply Side: How America Deploys its Assistance Compared to its Peers

Between 2002 and 2005, U.S. development assistance commitments were worth roughly 42 percent of what all other DAC member countries gave combined. Just over ten years later, this shrank to 25 percent on average between 2016 and 2020. [7] Although the U.S. gave marginally more in absolute terms in this latter period, the rest of the DAC more than doubled its giving to other countries, and America began to lag behind its peers (Figure 2). The PRC has become an increasingly important supplier of development finance following the 2008 Asian Financial Crisis, when it began outspending the U.S. 2-to-1 (Malik et al., 2021).

This comparison is one of apples to dragon fruits: the PRC’s assistance is mostly loans approaching market rates (88 percent), compared to the U.S., which uses more grants and no or low-interest loans (73 percent) at highly concessional rates (ibid). In recent years, the PRC has assumed a new role as a “rescue lender” in supplying balance of payment support to countries grappling with debt distress and cash liquidity problems (Horn et al., 2023).

Figure 2. U.S. Development Finance Compared to the OECD and China (1980-2021)

Sources: The U.S. and DAC data is captured from the OECD Creditor Reporting System (1980-2021). The PRC development finance for 2000-2017 uses data collected by Malik et al. (2021). Financial data for all donors includes ODA and OOFs.

America gives a lot in absolute terms, but it is not overly generous compared to other assistance suppliers—either as a share of our total federal spending or as a share of our Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Only once in the last 20 years has the USG deployed more than 1 percent of the federal budget to overseas assistance in 2005. The U.S. trails its DAC peers in the assistance it provides as a percentage of overall GDP. Moreover, American development assistance is plagued by high administrative costs: U.S. taxpayers pay nearly 1.5 times that of their peers in other DAC countries (9 versus 6 percent) in such fees.

Compared with other assistance suppliers, the U.S. has historically emphasized funding for basic health (6 percent) and education (3 percent) at higher levels than its peers. The U.S. is a world leader in funding related to reproductive health, outspending the rest of the DAC countries by nearly 3 to 1 in 2019. Comparatively, the rest of the DAC bankrolls economic development activities in sectors related to Banking and Financial services (7 percent) and Industry (3 percent) at higher levels than the U.S. Meanwhile, the PRC deploys the preponderance of its assistance to infrastructure-related sectors.

COVID-19 influenced global development assistance. The U.S. dramatically increased its spending by 28 percent overall in 2021, focusing on basic health, banking and financial services, and emergency response in 2021. The U.S. not only rose to the challenge of COVID-19 in absolute terms, but it also stood out in relative terms. In 2021, the U.S. disbursed nine times more than the average DAC country. Nevertheless, despite the size of this response, the U.S. has struggled to dislodge the perception that it mismanaged the crisis at home and abroad (Wike et al., 2020; Ameyaw-Brobbey, 2021).

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 also upended the development landscape. European nations extended temporary protection to over 5 million Ukrainians and committed billions of dollars in aid (UNHCR, n.d.; Kiel, n.d.). The U.S. stepped up, providing Ukraine nearly US$9.7 Bn in economic aid. However, with only partial data available at this point, it is an open question whether this is new and additional assistance versus displacing aid that would have gone to other regions.

The U.S. would not be alone in this: the UK, Sweden, and the Netherlands have all siphoned funding for in-country refugee support costs from their overall aid budgets, raising concerns about the availability of resources to other development priorities (Harcourt & Price, 2022). Beyond Europe, Russia’s invasion has disrupted global agricultural markets farther afield (FAO, 2022). In 2021, America mobilized US$1.1 billion in Development Food Assistance, eclipsing the US$764 million mobilized by the rest of the DAC.

America’s assistance efforts are also increasingly oriented towards responding to crises rather than advancing long-term growth, peace, and prosperity. In 2010, humanitarian assistance accounted for less than one-fifth (17 percent) of USG dollars spent on non-military assistance. By 2021, this had grown to one-third (33 percent). [8] Not strictly a COVID phenomenon, humanitarian assistance accounted for roughly a quarter or more of the non-military assistance budget as early as 2017. USAID is the lead humanitarian assistance agency, managing 60 percent of funding in this area, followed by State and Defense. [9] The degree to which the U.S. integrates its efforts across humanitarian relief, peacebuilding, and long-term development assistance is offered a more fulsome treatment in Chapter 3 of this research volume.

3.2 The Demand Side: How Leaders in the Global South Assess America’s Model and Offer

Leaders in low- and middle-income countries are abundantly clear about the problems they most want to solve: more jobs, better schools, and stronger institutions (Custer et al., 2021). This message has been consistent, even amid a global pandemic. Of course, the devil is in the details unique to each country: how do leaders view the path to delivering these public goods for their societies, do their citizens agree, and how do they determine whom they want to work with and to what end? U.S. policymakers must be self-aware of what our partners think we do best and in what situations they would prefer to work with alternative suppliers.

Between July 2022 and April 2023, AidData fielded an online survey of 1,650 Global South leaders to understand their perceptions of the United States as a global power and a development partner compared with five other bilateral actors: China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and a relevant regional power that varied by geography (Horigoshi et al., forthcoming). Leaders from 129 low- and middle-income countries shared their views, including mid- to senior government officials, parliamentarians, civil society, and private sector representatives. The survey responses are a departure point for thinking about areas of comparative advantage for the U.S. as it looks to focus and strengthen its development assistance efforts in the future.

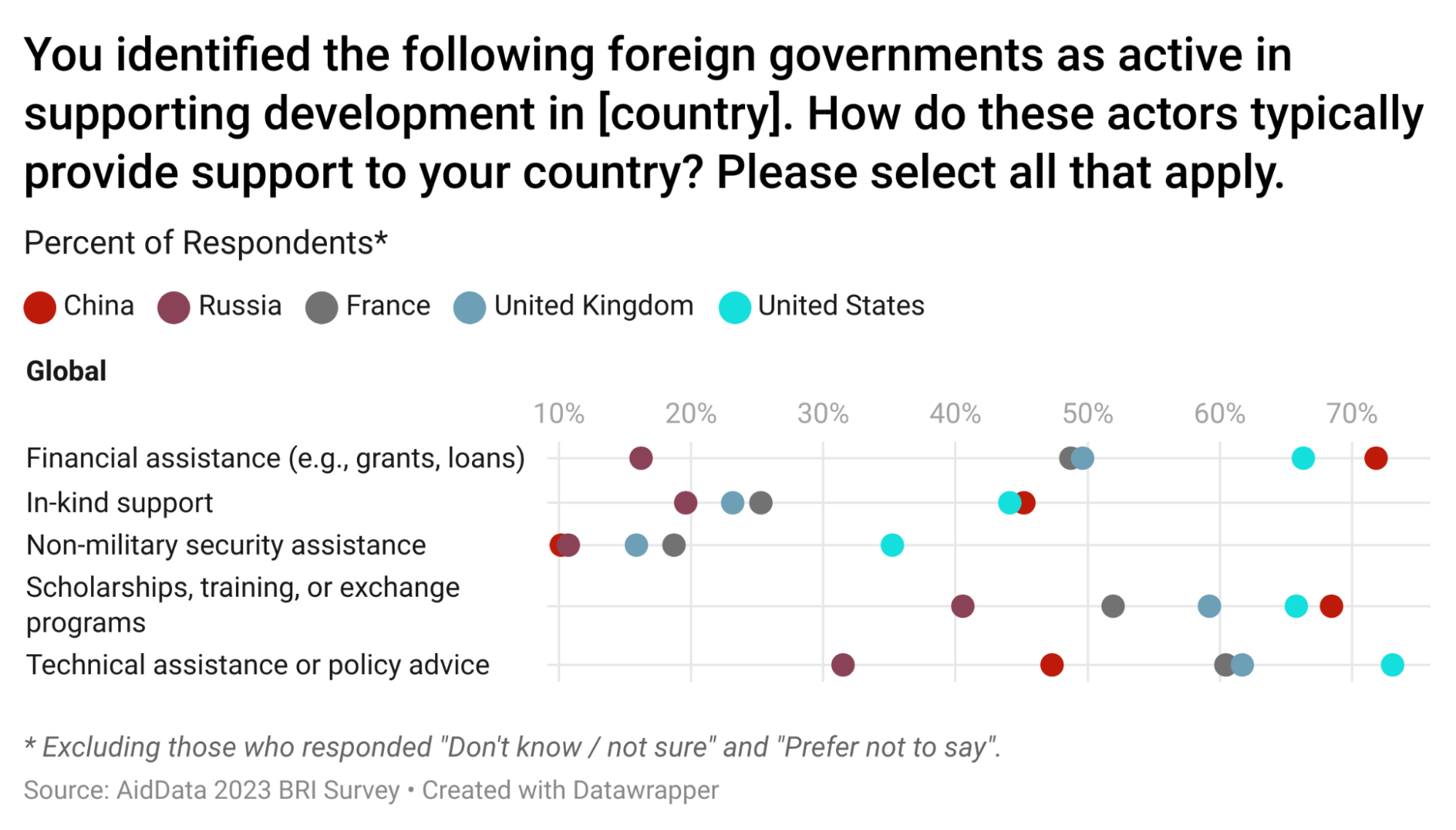

The U.S. sees itself as a development assistance player with a global reach, and leaders from 129 countries largely agreed (Figure 3). Four-fifths of leaders surveyed (81.7 percent) said the U.S. was somewhat or highly active in supporting overseas development in their country (Horigoshi et al., forthcoming). Leaders strongly associated America with providing technical assistance, policy advice (Figure 4), and financial assistance (ibid). Nevertheless, the pressure to maintain such breadth in its engagements has meant that the U.S. has left the door open to fall behind its peers in some geographies and surprising ways.

Sub-Saharan Africa has been an emphasis in U.S. development assistance priorities and financing over the last two decades. However, the PRC, not the U.S., is seen as more active in supporting development (Horigoshi et al., forthcoming). America’s third-place finish in both South Asia (behind India and the UK) and East Asia and Pacific (behind Japan and the PRC) is a bit of a letdown given the emphasis on the Indo-Pacific region across the last three administrations (ibid). The gap in these two regions appeared primarily driven by the perception that the U.S. was much less active in supplying financial assistance than the PRC (by a 20 to 25 percentage point margin) (ibid).

Figure 3. Global South Leaders Perceptions of the Degree to Which Foreign Governments Supported Development in Their Country Between 2012 and 2022

Source: Horigoshi et al. (forthcoming).

Figure 4. Global South Leaders' Perceptions on How Foreign Governments Supported Development in Their Country

Source: Horigoshi et al. (forthcoming).

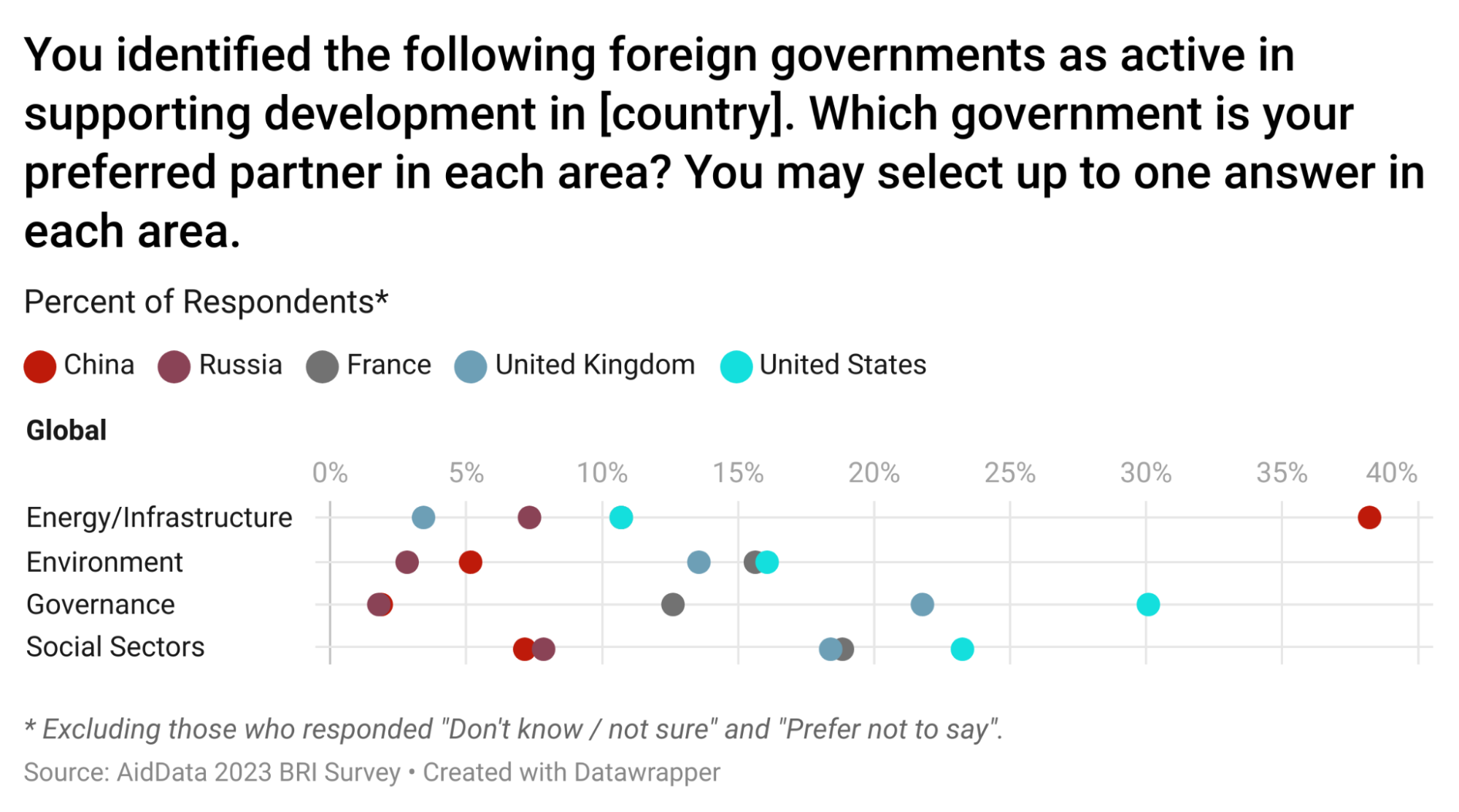

When Global South leaders think about their preferred partners by sector (Figure 5), they express an affinity to work with the United States as their top choice in the governance and social sectors (Horigoshi et al., forthcoming). The perceived U.S. comparative advantage is particularly strong in governance and rule of law across most regions, with the only outlier being South Asia (ibid). The U.S. was also consistently among the top choices in the social sector, along with other DAC donors like France and the UK. However, this lead was less pronounced and more volatile by region (ibid).

Equally striking is what leaders in the Global South say they do not want to work with the U.S. on: energy and infrastructure (Horigoshi et al., forthcoming). Instead, respondents sent a resounding signal that the PRC was their preferred partner for infrastructure at a large margin and consistently across all regions (ibid). U.S. political leaders should consider this feedback and rethink their compunction to compete with the PRC’s Belt and Road Initiative. Instead, the U.S. may get farther by doubling down in areas where counterpart nations see America as having a comparative advantage versus the alternatives: governance and the rule of law, and the social sectors (e.g., education, health) (ibid).

Figure 5. Global South Leaders on Their Preferred Development Partner by Sector

Source: Horigoshi et al. (forthcoming).

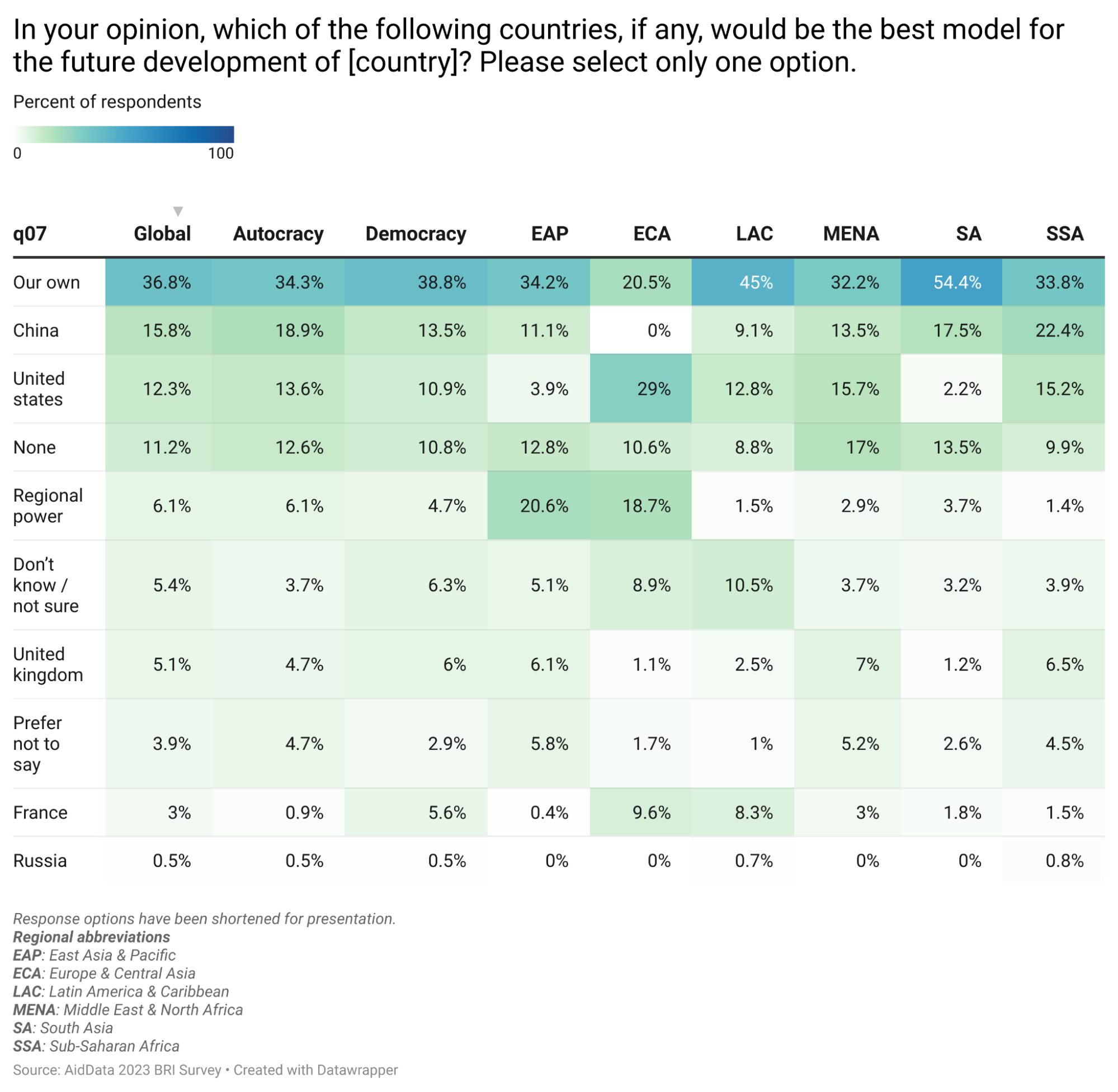

Finally, leaders also had the opportunity to reflect on what they saw as the best development model they thought their country should aspire to (Figure 6). One-third of respondents said their country should follow its own development path rather than another power. Nevertheless, when leaders looked farther afield for inspiration, they often turned to Beijing (15.8 percent) over Washington (12.3 percent) as the development model that held the greatest promise for their country. Comparatively, the U.S. model performed best in the eyes of leaders closer to home in Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as regions where America previously had a large historical presence in the Cold War (e.g., Europe and Central Asia) and post-9/11 (e.g., Middle East and North Africa) eras, though less so today.

It is particularly noteworthy that this preference for the PRC’s model held across respondents from both democratic and autocratic countries. If democratic leaders are equally enthralled with the PRC’s model as their authoritarian peers, it most likely is based on the economic growth appeal instead of a statement of political or ideological preferences. Again, in a sobering finding, given the U.S. emphasis on the Indo-Pacific over the last decade, America’s development model does not appear to win over many elites in South Asia (2.2 percent) or East Asia and the Pacific (3.9 percent). The U.S. performs somewhat better on this measure in Sub-Saharan Africa (15.2 percent). However, it is still seven percentage points behind the PRC, the preferred model for nearly one-quarter of regional leaders.

Figure 6. Global South Leaders on The Best Development Model for Their Country

Source: Horigoshi et al. (forthcoming).

4. Development Assistance Today: Learning from the Past, Looking to the Future

In this final section, we reflect on six lessons emerging from this retrospective assessment to carry forward into conversations about how to strengthen U.S. assistance in the future. In surfacing these lessons, we draw insights from the quantitative analysis of historical financing and the global perceptions survey, the desk research examining strategic priorities and operational practices from the Cold War to the present day, and the interviews conducted with policymakers and practitioners.

Lesson 1: Pivot From Strategic Ambiguity to Strategic Candor

The national security strategy signals the president’s vision of America’s global role, its top priorities, the instruments of national power it will use and how, and guidance for where the interagency will focus its resources (Pavel & Ward, 2019). However, the degree to which the national security strategy provides helpful standalone guidance for development assistance is unclear. Some administrations made grand statements short on specifics, elevating development alongside defense and diplomacy. Others provided a laundry list of priorities absent a clear hierarchy. High-level interagency processes have, at times, provided greater detail and focused attention to the connections between development assistance, foreign policy, and national security. Still, these processes failed to stick or move beyond paper into operational practice.

Development assistance is not pure altruism, but neither is it pure self-interest. Candor about what America wants to achieve and why can create flow-down benefits at an operational level. It allows for specialization across agencies, programs, and funds in that every activity need not do everything. Still, political leaders must see at a portfolio level that development assistance serves the breadth of America’s interests without subsuming one under the others. Second, it informs how the interagency, the White House, and Congress think about what success looks like, how to evaluate progress and make course corrections, ways to align incentives to reward outcomes, not inputs, and transparently report on results to demonstrate how development assistance delivers for America’s national interests. Third, it can elevate interagency dialogue and learning around how development assistance tools should work to support inclusive economic growth, peaceful democratic societies, and global public goods.

Lesson 2: Move From Operational Incoherence to Operational Complementarity

There has been a proliferation of agencies involved in development assistance. Many of these agencies have overlapping mandates, unclear jurisdictions, parallel structures, and separate funding accounts, leading to duplication of effort. Distrust in USAID prompted congressional and political leaders to form new agencies or vehicles as a workaround to advance their preferred development assistance priorities. Well-meaning attempts to foster coordination or improve accountability had the unintended effect of adding extra layers of bureaucracy rather than creating clarity.

Not all of these development assistance players are equal in their relative financial resources and political visibility. USAID, the Department of Agriculture (the primary provider of food assistance), State, and Treasury (responsible for multilateral contributions) are the big four players in development assistance dollars. [10] Defense and MCC have outsized visibility: they have vocal constituencies and strong bipartisan support but modest shares of the development assistance pie. [11]

Foreign assistance agencies exacerbate operational incoherence through active competition and lack of coordination. The underlying tension is partly political, as agencies jockey for position over limited resources and resist a loss of prestige or clout from a smaller mandate, and partly cultural in differing views on the ends, ways, and means of conducting development assistance programs.

Operational incoherence is more than an annoyance; it is a handicap to advancing U.S. national interests. With a development assistance budget of less than one percent of our federal spending, America must get the most from every dollar spent. The status quo disregards frustrating resource inefficiencies, the rise of parallel bureaucracies, and activities that work at cross-purposes. It is more complicated than it needs to be for others to partner with the United States. Rather than one interlocutor in a sector or country, bilateral and multilateral donors are confused by the bewildering array of interagency representatives they must deal with, and that may not speak with voice.

Lesson 3: Shift Accountability from Process to Outcomes

Insiders within U.S. foreign assistance agencies and the outsiders who work with them share a common discontent with runaway procurement and reporting requirements. Holding agencies accountable for the responsible use of taxpayer money is a reasonable objective—the problem is that the systems to procure, manage, monitor, and report on agency activities have become unreasonable, spawning perverse incentives and unintended consequences. Some of these requirements are congressionally imposed, others stem from presidential initiatives, but many are self-inflicted by the agencies.

Agency personnel are overwhelmed and frustrated by the tendency for congressional and executive branch leaders to add new layers of oversight and clearance without a commensurate willingness to evaluate whether the existing ones are essential. This attitude is one part time-saving mechanism and one part risk intolerance as personnel seek to avoid congressional scrutiny or public backlash that could arise in a case of waste, fraud, or abuse. An auditor’s mindset takes hold, focusing on tracking individual dollars spent rather than managing for results or innovating and learning rapidly from failure in the pursuit of greater impact. Intentional or not, this audit-driven culture rewards compliance and consistency to continuously fund the safe bets (highly familiar activities and implementers) rather than asking uncomfortable questions about whether these things generate the outcomes the U.S. or its partner nations want.

New technologies and artificial intelligence (AI) create opportunities to reduce the manual processing of large volumes of data and information or alleviate reporting burdens. Geospatial and remote sensed data have made it cheaper, easier, and faster than ever to conduct impact evaluations or support service delivery. However, agencies are frequently perplexed and slow to harness these game changers for effective design and delivery of development assistance. [12] Moreover, the U.S. is not well-positioned to work with counterpart nations in assessing ways to mitigate the risks and maximize the benefits of these tools in supporting public administration and economic growth in their countries.

Lesson 4: Don’t Allow Short-Termism to Undercut Long-Term Interests

USAID is vulnerable to seeing its long-term development mission displaced by the short-term imperatives of crises, conflicts, and disasters. Resources have a way of dictating priorities, and notably, over the last few years, more than one-quarter of funds managed by USAID have been focused on humanitarian assistance. [13] Is the growing short-term orientation of U.S. development assistance cause for concern and reform? If framed in security interests (i.e., protecting Americans from the spread of instability and disease), perhaps not, because humanitarian assistance allows the U.S. to respond quickly and decisively to mitigate the risk that a crisis or conflict worsens and spreads to other countries. However, if we’re concerned about other diplomatic, economic, or development interests, there is a greater risk of a mismatch if humanitarian assistance displaces attention and resources from longer-term efforts to promote growth, peace, and prosperity.

Another crucial calculation for USAID is that crisis and conflict situations are risky—money needs to be disbursed quickly, in dynamic environments, and with uncertain results. There is greater potential for things to go wrong with humanitarian assistance, which could make it difficult for USAID to overcome a persistent trust deficit with Congress. Of course, parceling out humanitarian versus long-term development assistance could exacerbate existing silos between these activities, making it challenging to ensure coherence and continuity in helping countries move from short-term crisis to long-term stability.

Lesson 5: Reposition U.S. Assistance to Be Responsive to Market Demand